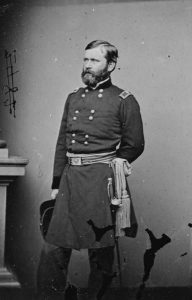

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]ajor General William B. Franklin was a Union corps commander in various theaters during the war, but battlefield success typically eluded him. Moreover, though an ally and favorite of Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan early in the war, Franklin heatedly clashed with each of McClellan’s successors, earning a reputation as a difficult subordinate who produced only mediocre results—the Battle of Fredericksburg catastrophe in 1862 and his part in Nathaniel P. Banks’ Red River debacle in 1864 were perfect examples. Yet after being unceremoniously captured in July 1864—not even in the midst of battle—Franklin was determined not to end the war in a Confederate prison camp. Displaying uncustomary bold and swift thinking, he pulled off a gutsy escape from his captors.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Gilmor admired Franklin’s tactful conduct, praising his ‘polite and gentlemanly bearing’[/quote]

The Red River Campaign was the final blotch on Franklin’s Civil War resumé. Besides the humiliation, all the 41-year-old commander could show for the campaign was a crippled left leg, injured at the Battle of Mansfield on April 8. A bullet had smashed into his leg, but failed to penetrate the flesh, leaving it severely bruised below the knee and nearly immobile. Returning north on leave after the campaign, Franklin spent some time with his wife in Portland, Maine, and then traveled to City Point, Va., in early July to visit his old West Point classmate, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. On July 10, he was on his way back north, perhaps unaware that he was heading into danger.

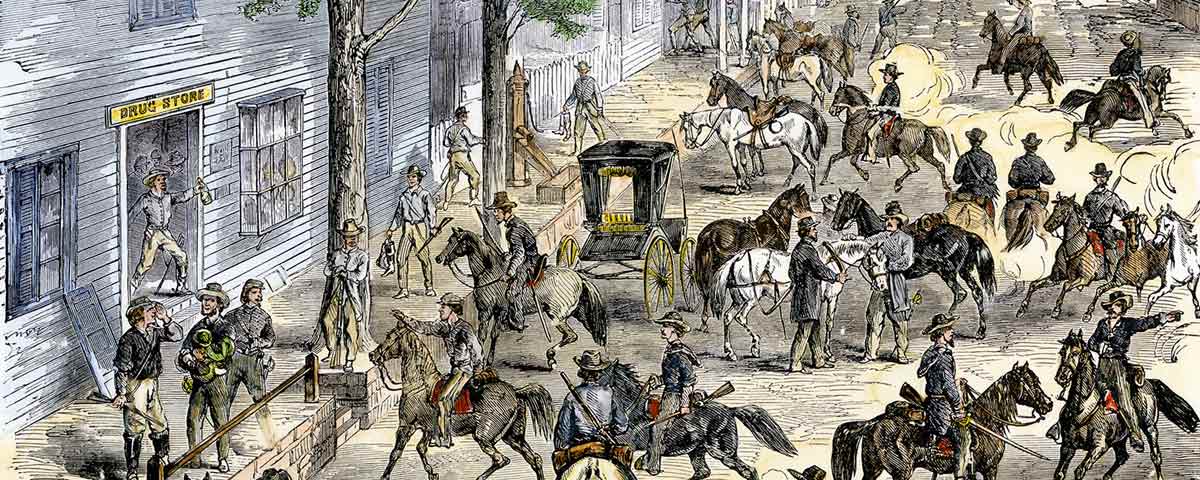

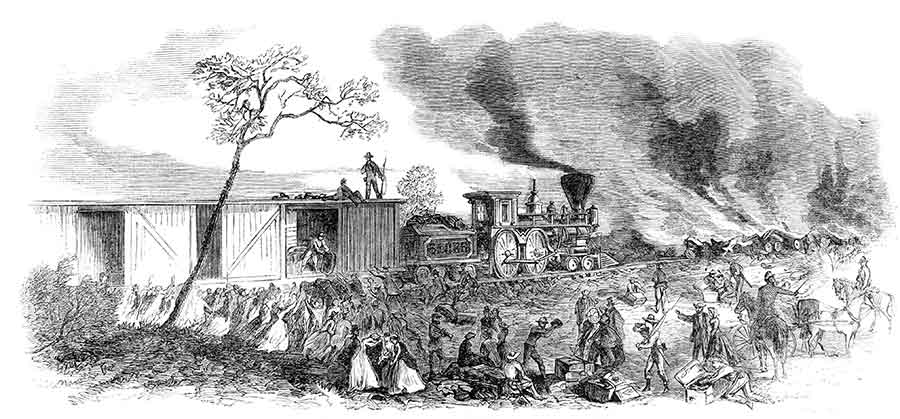

A spirited fight had taken place at Monacacy, Md., the day before, with Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s Confederates defeating a Federal force under Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace. Early then moved on Washington, D.C., reaching the outskirts of the capital on July 11. Meanwhile, Rebel Major Harry Gilmor, a native of the region, led a 130-trooper detachment of the 1st and 2nd Maryland Cavalry in a raid to destroy Union infrastructure between Washington and Baltimore, burning bridges, tearing up railroad track, and cutting telegraph lines. Franklin arrived in Baltimore amid the turmoil on July 11. Aware that Early’s gray legions were around, and eager to get back to Portland as quickly as possible, he boarded an 8:30 a.m. train on the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad, hoping travel by rail, rather than road, would help him bypass any Confederate threats.

It wasn’t until about 20 miles out of Baltimore that Franklin’s anxiety subsided. That reprieve turned to alarm, however, when the train unexpectedly jerked to a standstill about a mile after crossing the Gunpowder River Bridge, not far from Magnolia Station. The 26-year-old Gilmor had spotted the passenger train modestly chugging away in the vicinity of his detachment and ordered a captain and 20 of his cavalrymen to stop it. Gilmor’s cavalrymen boarded each of the cars, their boots clunking as they paced down the aisles. Frightened passengers kept their heads down, eyes locked to the ground—at least the Union sympathizers.

The troopers seemed mostly interested in nabbing prisoners, and they had been tipped off that Franklin happened to be aboard. Dressed in civilian attire and squeezed in the seat next to another Union officer, Franklin sat motionless for a half-hour trying to blend in, hoping he wouldn’t be spoted. Gilmor soon boarded the car rumored to be transporting the general. He demanded that the passengers point out Franklin, but received no response.

Gilmor made his way down the car row by row, probing one man at a time and demanding, “Are you Major General Franklin?” and requiring each person to provide papers or some form of credentials. Through the process of elimination, he came upon the cornered general, who spoke up and bluntly addressed the Confederate major, “I am the person you are looking for.” Franklin explained to Gilmor that his leg was disabled from his Mansfield wound, and that he could barely walk or ride a horse (likely hoping this would dissuade Gilmor from taking him captive). Gilmor informed him he was now his prisoner and that he would walk, and Franklin was pulled off the train without incident. The major admired Franklin’s tactful conduct, praising his “polite and gentlemanly bearing.”

Franklin and several other Union officers were detained under guard in a telegraph office, the civilian passengers removed, and the train put to the torch. Gilmor paroled most of the prisoners, not having enough horses to transport them back to Early’s army (most were invalids anyway). Five of the most desirable, including Franklin, were crammed into a commandeered carriage or wagon and placed under the custody of Captain Nicholas Owen. Owen’s party continued on until about midnight, encamping on Oliver’s Farm somewhere between Randallstown and Reisterstown, to rest and feed their horses.

While the Union prisoners resigned themselves they’d probably spend the rest of the war rotting away in a prisoner camp, Franklin plotted his escape. Feigning illness, he quietly laid down on some straw and pretended to fall sleep. He hoped the Confederate guards would relax their watch, sensing he posed no threat of flight. Captain Owen and each of the guards, one by one, followed Franklin’s example and fell asleep, exhausted from their continuous hours in the saddle. Franklin, eyes closed but wide awake, sat motionless as each man tucked up against the butt of his rifle and fell into a deep slumber.

Eventually Franklin lifted his large frame off the ground with some difficulty and stood. Fearing the guards would gladly shoot him if he was discovered, he crept as best he could to a nearby fence next to a clump of trees. Testing to see if they were “playing possum” as he had done, Franklin purposely coughed loudly, and made some racket, peering back as he did for signs of movement.

Getting no response from his Confederate guards, Franklin went for it. He scrambled over the wooden fence into the farmer’s field, glancing back one more time, and “ran” for his life. He hobbled along, slowed by his lame leg, across several fields and scaled several more fences. This continued for about 45 minutes. Not used to this kind of physical exertion, and with his leg starting to stiffen, Franklin concealed himself in some tall weeds and blackberry bushes near a tree line as daylight approached.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Guards woke to Gilmor cursing them when he realized Franklin had vanished[/quote]

Gilmor arrived back at Owen’s camp early that morning to check on the Union general. “As if a broadside had been opened upon them,” the guards woke to their wrathful commander cursing them when he realized Franklin had vanished. Twenty men were dispatched to hunt down the Union general. Hoping to restore Gilmor’s confidence in them, they knocked on doors and questioned the local farmers, searched empty barns, and scoured every field and bush in the area.

Franklin remained in that spot the following day. He intermittently peered through an opening in the brush, occasionally spotting Gilmor’s searching cavalrymen not far from his location. The July sun beat down on his face and mosquitoes tore at his skin, making these agonizing hours seem like an eternity. Astoundingly, he remained undetected.

That night, Franklin finally felt it was safe to move on. Hungry and fatigued, having sustained himself on only a handful of blackberries, he stumbled into a local farmer’s cabbage field, ripping a head from the dirt and eating roots and all. A newspaper later recorded that he became “completely bewildered” as his “over-wrought imagination made him fancy all sorts of queer things.” He started to hallucinate from a combination of fatigue, dehydration, and hunger, at one point seeing a crowd of medieval knights with lances and shields lining up to face him in battle—actually, it was just a field of corn. In a drunken-like stupor he stumbled onto a road, hoping it would lead to his salvation.

He suddenly came upon two men carrying bundles of hay. Knowing he wouldn’t be able to flee without alerting them—and unsure if this might be yet another hallucination—he casually strolled forward and bluntly asked what they were doing headed into the woods with that much hay. It was for their horses, concealed from prying Rebel cavalrymen, one of the men admitted. Their apparent pro-Union sentiments were enough for Franklin to reveal his identity, and soon the general was accompanying one of the men down a secluded trail to his farm.

The farmer’s family received Franklin “kindly and hospitably” and gave him his first meal in more than 24 hours and let him spend the night indoors. Franklin, however, spent the next day in the woods, hidden away in case Confederate troopers came knocking. Franklin wrote a note reporting that he was alive and needed a rescue party, and arranged to have it sent to the commanding officer in Baltimore.

A carriage and a Union cavalry escort arrived at the farm shortly to transport Franklin to safety. The ragged and scruffy-looking general arrived in Baltimore at 4:30 a.m. July 14. A few hours later, he was bound on a train for Philadelphia—a trip this time free of Rebel raiders. Nevertheless, though Franklin had been determined not to spend the rest of the war in a Confederate prison camp, he would find himself chained to a desk in an administrative role those final nine months—far away from the fighting.

A Cleveland native, Frank Jastrzembski is the author of Valentine Baker’s Heroic Stand at Tashkessen 1877: A Tarnished British Soldier’s Glorious Victory (2017) and contributes regularly to the blog Emerging Civil War.