Death was everywhere, and in his most terrific and disgusting aspects.…The flow of blood might be likened to the outbreaking of a torrent

—James Fenimore Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans

One early morning in August 1757 a column of some 2,300 Redcoats, provincials and rangers—followed by a smattering of civilians, including women, children, servants and slaves—formed up outside Fort William Henry at the south end of Lake George in the British province of New York. Under French military escort they began what promised to be a tedious 16-mile slog through dense woods along the military road to Fort Edward.

After a six-day siege punctuated by heavy bombardment Lt. Col. George Monro, commanding the fort’s British garrison, had acceded to the French terms of surrender. In accordance with Brig. Gen. Louis-Joseph de Montcalm’s terms of parole, Monro’s soldiers were allowed to keep their weapons and one small fieldpiece. It was a symbolic gesture only; their weapons were unloaded.

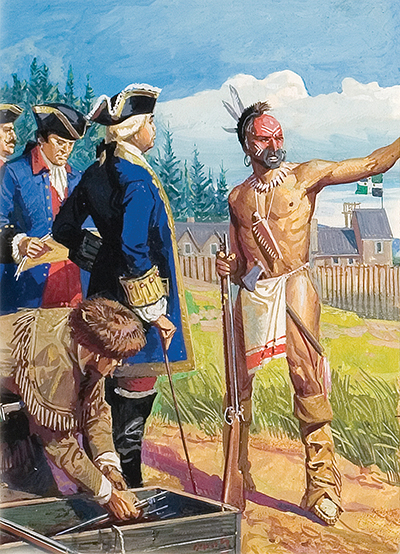

Montcalm’s white-uniformed soldiers watched in silence as their defeated foes passed. Such niceties of war, however, were completely lost on Montcalm’s allies—1,800 armed and painted warriors from various tribes. To them this was not how battles were won or celebrated. The fighting had always been about plunder, trophies and prisoners, and about avenging slain friends and loved ones. Now the victorious French expected them to stand by empty-handed as les Anglais, scalps intact, simply walked away. Within minutes the warriors would demonstrate in bloody terms their unwillingness to do so.

In the late 1740s the European conflict known to history as the War of the Austrian Succession ended with an uncomfortable peace between hereditary enemies Britain and France. It would not last. Soon enough they would be at each other’s national throats over their respective claims in North America.

Both countries owned vast tracts of land in the New World, and each wanted more. While Britain’s 13 colonies stretched from Georgia north to Maine, France claimed everything from Cape Breton Island west to the Great Plains and south to the Gulf of Mexico. The “more” after which both nations lusted was the Ohio River Valley, and—ignoring the fact various Indian tribes considered the vast region home—each claimed it.

The victorious French expected their Indian allies to stand by empty-handed as les Anglais, scalps intact, simply walked away

By 1753 tensions had reached the breaking point, as Britain and France each began building forts and clearing roads to defend their respective claims. In May of the following year fighting began in earnest when a young Virginia lieutenant colonel named George Washington ambushed a French scouting party in southwest Pennsylvania, killing some and capturing others.

That sparked a conflict referred to in the United States as the French and Indian War, regarded in Europe and Canada as a precursor to and part of the Seven Years’ War. In North America the no-holds-barred war stretched nine years, ranging up and down the Eastern seaboard from Virginia north into Canada.

The regular armies of the two great world powers predictably fought in the traditional European mode. The French and British also employed provincials—inexperienced colonial volunteers who tended to stray from the rules of war and act with considerably less discipline. To scout the unfamiliar country, both armies relied on the services of frontiersmen who knew and could function reliably in the wilderness. The French drew on allied tribal warriors and men from their provincial militia (milice), while the British formed companies of rangers—irregulars trained to fight and thrive in the backwoods.

Although both sides sought accord with the region’s various Indians, most tribes—including the Abenaki, Huron, Onondaga, Algonkian, Micmac, Nipissing, Ojibwa and Ottawa— lived alongside and sided with the French, who retained their loyalty through trade and Christian outreach. It was essential to their own survival the French maintain strong relations with their tribal allies, for while the land area encompassed within New France far exceeded that of their rivals, the British colonials in North America numbered between 1.5 and 2 million, as compared to only around 75,000 French.

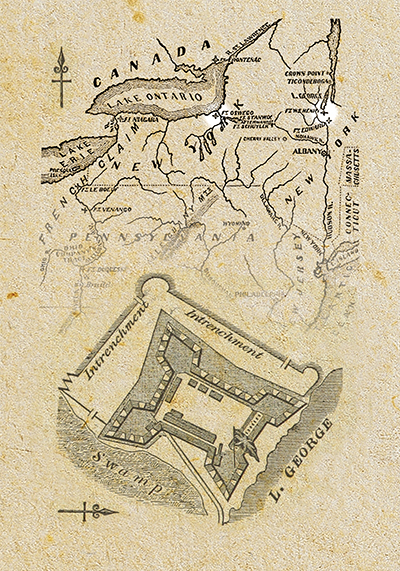

The first few years of the war favored the French, though in September 1755 the British triumphed in battle at the southern end of Lake George, a crucial gateway to New France to the north and the Hudson River farther south. Both sides swiftly set about erecting forts in the vicinity. The northernmost British installation, Fort William Henry, was designed and built by military engineer Capt. William Eyre on the lakeshore near the site of the recent battle. The French, meanwhile, raised Fort Carillon on the portage between the north end of Lake George and south end of Lake Champlain.

Initially, it seemed no one but the British high command really wanted to build Fort William Henry. On-site commander Maj. Gen. Sir William Johnson’s own officers refused, instead voting in a council of war to erect a simple stockade capable of “commodiously garrisoning 100 men.” The undisciplined colonial troops responsible for actually raising the structure also balked at the prospect, refusing to lift ax or adze. “The provincial soldiers,” historian Ian Castle writes, “were reluctant builders at the best of times.” Johnson was more forgiving of the men. “It would be both unreasonable and, I fear, in vain,” the general wrote in the aftermath of the battle they’d just fought, “to set them at work upon the designed fort.”

But build it they did. When ready for occupancy in November 1755 the earth-enforced log palisade was surrounded on three sides by a dry moat 30 feet wide and 10 feet deep, while the fourth side sloped down to the lakeshore. The fort featured four French-inspired corner bastions, while platforms and embrasures along the interior walls allowed for the placement of artillery and firing positions for the soldiers. Enclosed within its palisade stood a hospital, a magazine, a two-story barracks and brick-lined casements for storage. The only way in or out was across a bridge that spanned the dry moat.

Although the fort itself was built to accommodate a maximum of 500 soldiers, over the next several months the garrison fluctuated between 400 and 2,500 men. The additional troops, rangers and colonials were assigned to an entrenched camp some 750 yards to the southeast.

Montcalm sent an aide to demand the fort’s surrender, threatening Monro with his Indians, ‘the cruelty of which a detachment of your garrison have lately too much experienced’

In August 1756, while the British were formulating plans to attack forts Carillon, Saint-Frédéric and Frontenac preparatory to a campaign against the city of Québec, Montcalm captured Fort Oswego, near present-day Oswego, N.Y. After the British garrison surrendered, Montcalm’s Indian allies plundered the fort, slaughtered several of the sick and wounded in the hospital, and carried off women and children as captives. Although Montcalm successfully bribed them to cease, it was a harbinger of what was to come.

Montcalm then laid plans to attack Fort William Henry. Its defenders were far from prepared, many having succumbed to smallpox and scurvy. As stated in an officer’s report to Gen. John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun, the recently arrived commander of British forces in North America, the garrison comprised some 2,500 men, 500 of whom were sick. “They bury from five to eight daily,” the report to Lord Loudoun read. “The fort stinks enough to cause infection; they have all their sick in it.” Conditions at the neighboring camp were even worse. “Their camp [is] nastier than anything I could conceive, their necessary houses [outhouses], kitchens, graves and places for slaughtering cattle all mix through their encampment.”

The state of construction presented its own problems. “The fort itself is not finished,” the report noted, “one side being so low that the interior is seen into (in reverse) from the rising ground on the southeast side; also the east bastion has the same defect from the grounds from the west.” Rotting timbers framed the interior casemates, the powder magazine was perpetually damp, the well water undrinkable. The report went on to condemn the condition of the artillery and concluded with urgent recommendations for improvements—few of which were followed.

With the coming of winter the provincials’ enlistment term expired, and they returned home. This left some 100 rangers and 400 men of the 44th Regiment of Foot under the command of Captain Eyre, who soon earned promotion to major and continued to oversee construction. Lord Loudoun, who planned to use Fort William Henry as a springboard for his forthcoming campaign against the line of French forts to the north, ordered the wintering troops to build scores of boats, from flat-bottomed bateaux to sloops, with which to transport men and materiel.

Standing as it did on the frontier between British New York and New France, Fort William Henry was fated to attract considerable attention from the French. The first assault came in late March 1757. Some 1,200 men from the various French armed services, accompanied by 300 Abenaki and Caughnawaga warriors, marched south under the command of Maj. François-Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, son of the governor of New France. Along with their weapons his men carried 300 scaling ladders.

When sentries spotted Rigaud’s force approaching across the lake ice, Eyre immediately brought the men at the encampment into the fort. Though only 346 of the British regulars and rangers were fit for duty, they foiled French attempts to storm the fort. Rigaud offered Eyre the chance to surrender; but given the Indian outrages at Oswego the previous year, the officer wisely refused, whereupon the French set fire to the outbuildings and boats. Finally, after a heavy snow, Rigaud departed, having suffered seven killed and nine wounded.

Eyre’s casualties numbered just seven wounded, but the French and Indians had destroyed 350 bateaux, four sloops, two longboats and the fort’s supply of firewood. Lacking enough vessels, Eyre had to curtail lake patrols, and Lord Loudoun was unable to launch his campaign.

A week later Eyre was relieved by Lt. Col. George Monro, and the 44th by six companies of the 35th Regiment of Foot and two companies of rangers. As the weather cleared, some 800 provincials arrived from Fort Edward, as did two New York companies, and Monro established his headquarters at the encampment.

Lord Loudoun, still determined to launch an all-out attack on Québec, placed Brig. Gen. Daniel Webb in charge of the New York frontier, basing him at Fort Edward, 16 miles south of Fort William Henry. Loudoun had received false intelligence that Montcalm was gathering in his forces to defend Québec. In fact, the French commander intended to foil Loudoun’s plans by preemptively destroying Fort William Henry.

In late July Monro sent out a reconnaissance in force—350 men in 22 whaleboats that had survived Rigaud’s attack. They were ambushed by a superior force mainly composed of Indians, who slaughtered nearly 100 men and took another 150 prisoner; only four boats escaped. The carnage was horrific. “Some were cut to pieces,” recalled Father Pierre Roubaud, a French Jesuit missionary accompanying the Abenakis on expedition, “and nearly all were mutilated in the most frightful manner.”

The day after the survivors’ return Webb dispatched an additional 1,000 men and six cannons to Fort William Henry, boosting Monro’s strength to 2,351 men, though many remained seriously ill. The transfer left Webb with only 1,600 men at Fort Edward.

By then Montcalm had assembled more than 6,200 regulars, provincials and milice, as well as 1,800 warriors from 18 Indian nations. Having heard of the British trouncing at Oswego, some had traveled more than 1,500 miles on the promise of scalps, prisoners and plunder.

Montcalm split his force in two, sending one 2,500-man party down Lake George by boat and personally leading the other by land along the western shore. On the night of August 1–2 the parties reconnected, and Montcalm’s main force boarded the lake vessels. Among its hundreds of bateaux and canoes, the huge fleet included 21 double-bateaux pontoons on which to ferry the army’s 45 cannons and assorted mortars.

The next morning Montcalm camped within 5 miles of the fort. Monro was alerted to the enemy presence when two British boats patrolling the lake came under attack. He wrote Webb—his first of three dispatches to Fort Edward that day—seeking reinforcements. Meanwhile, Montcalm sent an aide to demand the fort’s surrender, threatening Monro with his Indians, “the cruelty of which a detachment of your garrison have lately too much experienced.”

Assuming Webb would send reinforcements, Monro refused. Meanwhile, Webb, having been duped by a French prisoner into believing some 11,000 to 12,000 Frenchman had arrived at Fort William Henry, chose to remain behind the walls of his fort. He sent a response to Monro, advising surrender: “You might be able to make the best terms as were left in your power.”

The message was intercepted; Monro would not learn for three days that Webb wasn’t coming. Instead, Webb wrote to Albany for reinforcements, little considering the time it would take for the messenger to reach his destination and for a relief party to return.

In the interim the French extended their artillery batteries around the fort, while the Indians kept up a constant harassing fire. Monro had only 17 cannons, three mortars, a howitzer and 13 swivel guns, and within a short time the overtaxed barrels of his three most powerful cannons burst. The French gunners had yet to answer.

On August 7, the fourth day of the siege, Montcalm had an aide deliver to Monro the intercepted letter from Webb, advising surrender. Whether out of disbelief or defiance, Monro again tried to stir Webb to action, writing, “Relief is greatly wanted.” Holed up in Fort Edward, Webb continued to dash off dispatches to various militia colonels and provincial governors, begging them to send soldiers, without whom “this whole country must be deserted and given up to the enemy.”

As Montcalm’s aide regained his lines, the French artillery opened up on Fort William Henry. The bombardment took a terrible toll, as French shells pulverized the walls and burst within them, killing and injuring many. At the same time the French staged attacks on the encampment, taking British lives Monro could ill afford to lose. Still he stubbornly held on, issuing an order that any man showing cowardice or proposing surrender “should be immediately hanged over the walls.”

The outcome was inevitable. Shortly after daybreak on the sixth day Monro hoisted a white flag and sued for terms. He had lost 45 men killed and 70 wounded, as compared to the enemy’s 13 dead and 40 wounded. Only five of his original 17 cannons remained serviceable. His vastly outmanned and outgunned garrison had acquitted itself well.

Following the British surrender Montcalm granted Monro and his men the “full honors of war.” Permitted to keep their weapons and personal possessions, as well as one symbolic cannon, the British officers and men would be escorted to Fort Edward. In exchange Monro agreed neither he nor his men would take up arms against France for 18 months.

Convincing Montcalm’s Indian allies to adhere to the terms was another matter. They had not traveled this far to leave empty-handed. Although Montcalm elicited a promise that the Indians would exercise restraint, he had seen them in action on at least two recent occasions and would have been naive to expect obedience.

Parties of warriors—all of whom, one Massachusetts officer recalled, carried “a tomahawk, hatchet or some other instrument of death”—roamed the fort looking for plunder. Finding little, they turned their weapons on the sick and wounded while the French and Canadian troops looked on. The Indians then dug up several corpses in the cemetery, taking scalps and clothing from the remains as prizes. Among the bodies disinterred was that of Capt. Richard Rogers, brother of famed ranger commander Maj. Robert Rogers. “My brother,” wrote the latter, “died with the smallpox a few days before this fort was besieged, but such was the cruelty and rage of the enemy after their conquest that they dug him out of his grave and scalped him.” Ironically, in addition to scalps and clothing, the Indians would carry the smallpox virus back to their respective villages, with catastrophic results.

When the column, which included civilian carpenters as well as women and children, walked out of the fort and the encampment, hundreds of Indians stalked them, at first offering to buy their baggage and then simply taking it. When Monro complained to the French officer in charge of the 250-man escort, he was advised to surrender all baggage and packs in hopes that would placate the Indians. It did not.

A more aggressive contingent of Abenakis was next to attack the column, at first stripping the men of their clothing and guns, then dragging them off singly to beat, hack and stab them to death. “This butchery,” the French missionary Father Roubaud recalled, “which in the beginning was the work of only a few savages, was the signal which made nearly all of them so many ferocious beasts. They struck, right and left, heavy blows of the hatchet on those who fell into their hands.”

‘They struck, right and left, heavy blows of the hatchet on those who fell into their hands’

The vastly outnumbered French escorts did nothing to stop the mayhem, some officers advising the British to “take to the woods and shift for yourselves.” Fortunately, the attack soon ran out of steam. “The massacre was not,” Father Roubaud noted, “so great as such fury gave us cause to fear. The number of men killed was hardly more than 40 or 50.”

The French troops eventually regained some control over their allies. Montcalm himself, noted Father Roubaud, fought “with authority and with violence” to reclaim prisoners from the Indians. Hundreds, however, were dragged off to be sold or taken into their captors’ tribes. By day’s end most of the Indians had returned home with their prizes, fewer than 300 remaining in French service. In the absence of most of his Indian allies, as well as the 1,300 milice—who returned home for the harvest—Montcalm’s campaign was finished.

Over the next several days some 600 panicked survivors from Fort William Henry wandered into Fort Edward, their versions of the attack exaggerated with every telling. Word spread throughout New York and New England of women horribly abused, babies dashed against rocks and men scalped alive. The rumored number of those killed or taken prisoner soared as high as 1,700. Then, on August 14, Montcalm—who had realized his objective by demolishing Fort William Henry—sent word to Webb he was holding Monro and 500 soldiers and civilians for their own protection and would shortly have them escorted to Fort Edward.

While a precise tally proves elusive, somewhere between 50 and 174 unarmed soldiers and civilians were massacred in the march from Fort William Henry. Such atrocities were not uncommon on the frontier, as evinced by the Oswego attack and Lake George ambush. And they were perpetrated by both sides. Two years after the Fort William Henry massacre Robert Rogers himself staged an attack on a sleeping Abenaki village, killing its occupants indiscriminately, though the desecration of his brother’s body doubtless served as motivation.

A year after the razing of Fort William Henry the British succeeded in taking Québec, and in 1763 the war ended in their favor. For nine years the frontier had been soaked in the blood of soldiers, civilians and Indians alike. Yet more than two and a half centuries later popular belief—fueled by oral tradition, James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans and Hollywood’s sensationalist versions of the siege—has singled out the massacre at Fort William Henry as the most egregious event of that bloody war. MH

Ron Soodalter is a frequent contributor to Military History. For further reading he recommends Fort William Henry 1755–57: A Battle, Two Sieges and Bloody Massacre, by Ian Castle; The Legacy: Fort William Henry, by David R. Starbuck; and Betrayals: Fort William Henry and the “Massacre,” by Ian K. Steele.