The San Antonio Rose II, steel propellers slashing the skies above the Celebes Sea, was hurtling toward hell at 200 miles an hour. The B-17 was leading a flight of 10 B-25s and two other Flying Fortresses, and had just reached the palm-fringed coast of Mindanao when a wall of black cumulus clouds suddenly appeared, towering to 20,000 feet and seeming to bar any approach to the southern Philippine island.

None of the pilots thought of throttling back. Not this close. Not with Ralph Royce, an unflappable aviator who had built his career on long flights under less-than-ideal conditions, personally commanding the mission. Navigators hastily plotted course corrections and the bombers proceeded to their destination: a secret military airfield in the highlands of northern Mindanao. As Royce’s bomber banked to bypass the rumbling tropical thunderheads, the 51-year-old brigadier general and the plane’s ranking passenger calmly bit into a chocolate bar and flipped to the next page of his book, The World’s Greatest Adventure Stories.

The storm, not to mention Royce’s choice of reading material, was apropos. It was Saturday, April 11, 1942, the conclusion of America’s darkest, most turbulent week of the war. Two days earlier, 75,000 American and Filipino troops on the Bataan Peninsula had surrendered, the largest capitulation in U.S. military history. That devastating defeat was the latest in a staggering series of Allied setbacks in the Pacific stretching back to December 1941, and news of the surrender cast a pall over the nation. Never was the need for heroes greater.

In the days to come, Royce and his men flew into that void and executed the United States’s first large-scale offensive bombing mission of the war. Their sorties, originating deep behind enemy lines, inflicted significant physical and psychological damage upon Japanese forces occupying the Philippines. The crews also evacuated key military and civilian personnel from the doomed territory. And they employed death-defying, unconventional tactics, quite literally on the fly, that provided a blueprint for aerial victories that would turn the tide of war in the southwest Pacific. Yet due to a twist of timing, only days after the triumphant completion of their mission, their sensational, singular adventure story all but vanished from public consciousness.

The operation that would come to be known as the Royce Special Mission to the Philippines, or the Royce Raid, was conceived not by a young pilot or air officer, but by an old army cavalryman. In late March 1942, Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainwright, commander of the besieged troops on Bataan and Corregidor, had radioed a plea to General Douglas MacArthur for bombers to clear a path for supply ships blockaded in the Philippine Visayan Islands. MacArthur ordered the commander of the Australia-based Allied Air Forces in the southwest Pacific, Lieutenant General George H. Brett, to proceed—despite Brett’s protestations that such a mission was impossible.

As if the distance wasn’t daunting enough—4,000 miles of enemy-controlled skies and seas separated Manila from Australia’s northernmost air base, at Darwin—Brett’s command was paralyzed by the Pacific pandemic of defeatism. In the wake of Japan’s early conquests, a flood tide of refugee military personnel had inundated Australia. But there was little with which to arm them, especially the pilots. Aerial assets included Australian Wirraway trainers and Hudson bombers, and a handful of worn-out B-17s and P-40 fighters.

Brett had access to a pool of officers who could lead the mission, but given the circumstances there was really only one choice: Ralph Royce. The West Pointer had served with the 1st Aero Squadron in the 1916 Mexican Punitive Expedition and in World War I, when he received the French Croix de Guerre for flying the squadron’s first reconnaissance mission over enemy lines. In January 1930, Royce shepherded the 1st Pursuit Group on a long-distance test flight through freezing temperatures from Michigan to Washington state that earned him the prestigious Mackay Trophy. Four years later, Royce again braved blizzards and ice piloting a B-10 bomber on an experimental expedition led by then-Lieutenant Colonel Hap Arnold from Washington, D.C., to Alaska.

Yet for all of Royce’s experience with long journeys and long odds, he could not magically summon an air fleet. But there was someone in Australia who could.

As a teenager in Arkansas in 1917, Paul Gunn was caught running moonshine. A judge gave him a choice: go to jail or join the service. Gunn chose the navy, where a career as a chief petty officer and carrier pilot unlocked talents for mechanics and aviation that would become legend. By the time the United States entered World War II, Gunn, 42, had retired from the navy and was living in the Philippines with his family, managing Philippine Airlines. MacArthur called him out of retirement with a captain’s commission and orders to shuttle VIPs and supplies on the airline’s twin-engine Beechcrafts.

When the capital city, Manila, fell to Japan in January 1942, Gunn’s wife and four children were interned. Japan’s defeat and his family’s freedom became Gunn’s obsession. Called Pappy, the bourbon-loving flier was all over the southwest Pacific, swaggering around wearing a pair of shoulder-holstered .45 automatics and exhaling clouds of cigar smoke, exhorting superiors and civilians with salty language, and exhausting men half his age while pulling double duty uncrating and assembling A-24 Dauntless dive-bombers and flying combat missions on Java and supply runs to the embattled Philippines—one of which, on March 20, 1942, earned him a Distinguished Flying Cross.

Fate guided Gunn on that flight, as it did days later on a moonlit night at a field in Melbourne, Australia. Gunn was scouting for machine shops that could service American transports when he made an exhilarating discovery: two dozen B-25 Mitchell medium bombers belonging to the Netherlands East Indies Air Force, which had no pilots to fly them. Gunn despised the Dutch—he felt American forces had done a disproportionate share of the fighting in Java—and the find left him furious. He had recently arranged a transfer to the 3rd Bombardment Group, which was still awaiting delivery of aircraft from the United States, so he flew 1,500 miles from Melbourne to the group’s base at Charters Towers airdrome in north Queensland and marched straight to the office of his commanding officer, the 6-foot-6 Colonel John “Big Jim” Davies.

“Jim, I just saw 24 of the prettiest B-25s you would ever want to see,” Gunn said.

Davies was frustrated with his planeless outfit’s inability to fight in the Philippines. But when Gunn suggested they grab the B-25s, he objected. A military court could call that theft.

“Goddamit, Jim, the planes have been sitting there for two weeks,” Gunn barked back.“I want you to get off your ass. Go to one of your buddies that’s a general and ask him, beg him, threaten him, but come back with authorization to pick up our planes from Melbourne! I’ll have them ready for combat in a few days and we can give the Australians in New Guinea some much-needed help!”

Two days later, with orders secured from an accomplice at Far East Air Force Advance Headquarters in Brisbane, Davies launched a daring plan. He would snatch the Dutch bombers and when caught, as was inevitable, simply claim he had taken the wrong B-25s.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Davies, Gunn, and 22 other pilots rode the mail plane to Melbourne. There, aided by paperwork authorizing the pickup of the 3rd Bomb Group’s aircraft, they made off with 12 Dutch B-25s. By the time they stopped at Brisbane to refuel, complaints and condemnations had caught up with them. But Gunn duped a duty officer and the 3rd Bomb Group bandits were back on their way, parking the purloined bombers in revetments at Charters Towers in the early morning hours of April 3.

Protests by the American and Dutch ambassadors failed to make a difference. And the Dutch were destined to lose another battle: While prepping the bombers, Gunn discovered their Norden bombsights were missing and brazenly flew one of the planes back to Melbourne to secure them. A standoff with a Dutch supply officer ended when Gunn drew both his .45s; he returned with the Nordens. “Military rules and regulations bothered him not,”Lieutenant Harry Mangan, a pilot who would participate in the Royce Raid, said of Gunn. “Rules be damned. He was fighting a private war.”

On April 6, Davies and Gunn received urgent orders to report to the Melbourne headquarters of the U.S. Army Forces in Australia. Fearing disciplinary action, they instead were rewarded with a mission. Two days later, they met General Royce in a top-secret briefing. Royce told them that to increase the B-25s’ range, extra fuel tanks would be installed. The bombers, Royce explained, would stage out of secret fields on Mindanao still in friendly hands. The latest intelligence and weather reports would guide their target selection.

Also present was Captain Frank P. Bostrom, a B-17 pilot from the 19th Bomb Group, which would be teaming up on the mission. Bostrom knew the route well; just weeks earlier he had flown MacArthur and his family from Mindanao over the Celebes Sea, Timor, and New Guinea to Australia. Since only six B-17s were available, Royce got just three. Ultimately 10 B-25s would participate in the mission—one with Pappy Gunn at the controls.

The news of the mission surged through Charters Towers and, although pilots didn’t know the objective, volunteers deluged Davies. So fierce was the competition that Captain Ronald Hubbard, scratched as a pilot because of dengue fever, volunteered to be a bombardier. Optimism was becoming contagious. On April 10, Brett ordered a Distinguished Service Cross, the army’s second highest award for valor, be readied for Royce’s return. But when the expedition landed in Darwin the morning of April 11 en route to Mindanao, bad news caught up with them. Two days earlier, Bataan had surrendered.

The needles on their fuel gauges tilting towards empty, the bombers were about to be swallowed by the storm swirling above Mindanao when, “as if by magic, there was a hole in the cloud cover,” Lieutenant Frank Bender, co-pilot to Pappy Gunn, recalled. Below them, three gunshots punctured the silence at an airfield the U.S. military had bulldozed out of one of the Del Monte Corporation’s pineapple plantations. The rifle reports— Del Monte Field’s air-raid signal—sent men scrambling for cover and the bombers scudded to successive landings before wide-eyed Del Monte personnel, none of whom had ever seen a B-25.

Brigadier General William Sharp, the commander of a few thousand Allied troops still carrying on the fight in the southern Philippines, ushered Royce into the Del Monte Officers’ Club, which would serve as the mission’s operations center. Bataan’s fall meant there was no longer a need to attack near Luzon. Yet they had come to attack and that’s what they were going to do: make aggressive, archipelago-wide strikes on Japanese ships and naval and air installations, focusing on the ports of Davao and Cebu, until they ran out of bombs or fuel. They would also evacuate various civilians, reporters, and military personnel MacArthur had cleared to leave the islands.

As a precaution against enemy reconnaissance, Davies led five B-25s to a strip at Valencia, 40 miles away, where Filipinos camouflaged the planes with jungle foliage. At both fields, crews pumped fuel and swapped the auxiliary fuel tanks for ordnance before bedding down beneath their planes.

Royce’s raiders found it difficult to sleep.“Here we were surprising the enemy for the first time,” Bender said. “What a pleasure [to be] going over the target after having taken so much grief without having anything with which to hit back.”

The raid’s namesake, however, wouldn’t be going with them. Official word was that the San Antonio Rose II, in which Royce was to fly, needed repairs to its number 3 engine. But it’s likely that army forces headquarters had grounded Royce to deny the Japanese a propaganda coup should he be lost. Royce would instead choreograph the raids from his “war room.”

The B-25s drew first blood around bustling Cebu Harbor, 150 miles north of Del Monte Field, at first light. Half struck a Japanese airfield; the rest bombed the harbor from 4,000 feet. As American bombers registered hits on two large ships, Davies’s B-25 loosed five 500-pound bombs, which bombardier Ronald Hubbard watched walk through “dockside warehouses setting off several fires and dockside explosions.” The B-25s then raced home to refuel and re-arm for follow-up attacks the next day.

The two B-17s were also on their way home after hitting targets in Luzon. One had sunk a tanker near the southern port of Batangas; the other Flying Fortress, Frank Bostrom’s, had bombed the runway and hangars at Nichols Field, a former American air base near Manila. Bostrom then zoomed past Corregidor, waggling his wings in view of its dazzled defenders.

Royce, riveted to his radio, was ecstatic. “It was a picnic,” he recalled.

But no sooner had the B-17s landed at Del Monte than three dive-bombing Japanese floatplanes damaged them and destroyed San Antonio Rose II. Gunn and other mechanics repaired the two Flying Fortresses so they could return to Australia the next day loaded with evacuees.A groggy Gunn then took off in his B-25 for the second—and most fatefully significant—day of the mission.

On Gunn’s first run over Cebu, a large freighter evaded his bombs. Incensed, he instinctively plunged into a steep dive. Minutiae and memories of Gunn’s navy days went ricocheting through his mind: the arcane knowledge that ships’ guns automatically stop firing when lowered below 18 degrees, to keep them from blowing themselves out of their mounts. A pilot flying low enough could get unbelievably close if he dared to. He also flashed on the lucrative pots awarded to the pilot who could skip a bomb across the water the most times during dive-bombing training.

Gunn ordered the turret gunners and bombardier to fire their .50-caliber machine guns forward; he’d release the bombs.“We’re going in low,” Gunn told them. “So low you’ll think we’re swimming.” Within seconds, the B-25 was 100 feet off the waves, guns blazing, screaming straight for the ship’s bridge. Squeezing the trigger and squirming in the Plexiglas nose, Gunn’s bombardier pleaded with him to pull up, but Gunn had tunnel vision.“Spray the deck! Spray the deck!” he yelled over the intercom before releasing two 500-pound bombs and yanking back on the stick. One bomb convulsed the ship in fiery explosions.

G-forces pinned Gunn to his seat, but could not restrain his emotions. “That’s the way to do it, boys!” he yelled as he whipped the B-25 into a crisp, 180-degree turn for another run at the enemy. “That’s the way to get ’em!”

“Yeah, that’s the way,” huffed Gunn’s hyperventilating co-pilot, Lieutenant Bender,“If you want to get us all killed, that’s the way.”

Flush with adrenalin, Gunn dove again, resulting in catastrophic hits with 500-pounders that skipped across the surface to slam into the ship at the water line, shearing it in half.

Soon, the other B-25 pilots were emulating Gunn. The raid was stunningly successful: 10 B-25s hit Davao in the morning and four more in the evening, and four bombers pounced on Cebu. Despite antiaircraft fire and fire from Zeros and seaplanes, the strafing B-25s stitched warehouses, docks, and fuel dumps, mowing down men and sparking huge fires. The fat 500- pounders and shrapnel-spattering 100-pound fragmentation bombs with instantaneous fuses whistled a symphony of destruction upon the Japanese. At Davao, Davies’s copilot, First Lieutenant James McAfee, saw three of five bombs—those with “Mother,”“Daddy,” and “Sally” scrawled on them after members of his family—obliterate a transport, a wonderful catharsis.“I was scared to death,” admitted one pilot, Major William Hipps. “But I’ve never had so much fun in my life.”

They were the first Allied bombers to strike the Japanese and inflict real damage, as well as shock. Over Davao an enemy pilot sidled his plane up to Hipps’s ship.“He was so close we could see his face—and it just registered blank amazement,”Hipps recalled. “He didn’t seem to know where we came from or how we got there. He never found out either—the rear gunner got a direct hit on his motor and a few seconds later he went down in flames.”

Back at Del Monte, bombs sent Royce running to a dugout five times. He even helped put out a fire. More enemy planes, as well as ground forces, were undoubtedly on their way. As smoke mushroomed over Cebu and Davao, the general decided that it was time to leave the Philippines. He ordered the B-25s home.

Gunn had made up his mind, too. Winging back to Del Monte, his scattered thoughts coalesced. This was the way to fight with a B-25. Get right down on the water with the ships and blow them to hell. He couldn’t wait to tell Davies of his tactical revelations. But the news would have to wait—he had another mission.

Landing that evening at a small strip on the island of Panay, 220 miles to the north, Gunn hurriedly took on four high-priority passengers: UPI war correspondent Frank Hewlett, two Japanese American intelligence operatives, and a Chinese military attaché. Back at Del Monte, other priority evacuees— pilots, staff officers, and a quinine expert—crammed aboard the remaining B-25s before they took off and headed for Darwin at 12:50 a.m. on April 14. It would be more than two years before large American bombers would again appear in the skies over the Philippines.

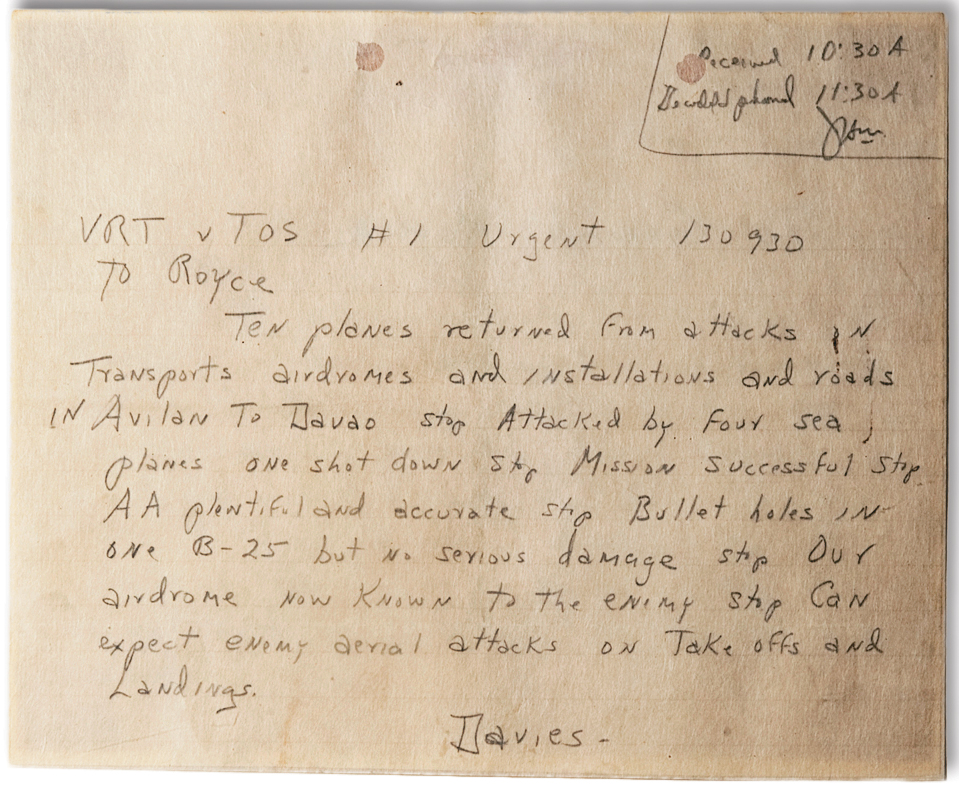

Royce’s Raiders had departed Australia in secrecy and anonymity, but returned to fanfare. Royce received a priority telegram from U.S. Army chief of staff General George C. Marshall: “Good work stop Congratulations.” The April 16 New York Times called the raid “the most spectacular aerial thrust of the Pacific War.” There were press conferences and popping flash bulbs, as well as a ceremony during which Royce and Davies were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Gunn, Bostrom, and the other dirty, exhausted pilots received medals, too, but they cared little for the accolades or attention.“Just give me a two-inch beefsteak and bed for a week,” James McAfee said.

It was just as well. While Royce’s patchwork aerial armada had been descending to storm-shrouded Mindanao, a secret naval task force led by the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, 16 B-25s lashed to its flight deck, was sailing toward a higher-profile target: Japan (see “The Avengers,” ). The leader of this near-simultaneous operation was Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle.

Doolittle’s men had been equally unaware of Royce’s adventure. Captain Ted Lawson, in his book Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, described the“sick feeling”he and his fellow Doolittle Raiders got when a garbled report of the Royce attacks reached them on the Hornet and “word spread through the ship that Tokyo had been bombed by four-motored American planes” identical to those they had aboard.

News of the Doolittle Raiders’ April 18 strike against targets in Japan reached the world two days after word came of the Royce Raid, banishing the accomplishments of Royce and his men— first to the back pages, then to obscurity. Yet the effects of Royce’s raid carried into 1943 and beyond, perhaps impacting the Pacific War more extensively than the more famous mission.

Royce’s men navigated a record 4,000 miles, operated for two days deep within enemy-held territory, sank eight ships, shot down five planes, inflicted incalculable damage on Japanese installations and personnel, suffered no casualties, and brought home all but one—the San Antonio Rose II—of their invaluable birds. Furthermore, those immediately tangible results paled in comparison to the raid’s short- and long-term effects at the individual, local, and theater levels. The mission rescued nearly three dozen important individuals from certain captivity or death, reinvigorated MacArthur’s command, and signaled America’s resolve—not only to the subjugated people of the Philippines, but to anxious Australians as well.

Pappy Gunn went to work in his hangar laboratory almost immediately afterward, reconfiguring B-25s and A-20s into gunships. The mad scientist’s experiments, coupled with innovations in ordnance and the revolutionary tactics he conceived over Cebu, synthesized into a deadly technique for skip-bombing and low-level strafing that would bring astonishing results at the Battle of the Bismarck Sea in March 1943 and render a devastating attack on the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul the following November. Gunn was reunited with his family after the liberation of Manila in early 1945.

Ralph Royce would receive a promotion to major general in June 1942, and serve in Europe, the Middle East, and the United States through the war’s end. But, as his Distinguished Service Cross citation supports, it was in the early days of the Pacific conflict,“at a time when defeatism was…the mandatory doctrine of the day,” that Royce and his raiders left their mark through their “determined combative spirit of aggression…, heroism, and extraordinary achievement.”

“We came back cocky,” said a prescient Royce after the raid, foreshadowing the whirlwind of Allied aerial offensives that would descend upon the Japanese.“That’s the way we should and will come back every time, too. When you have men who feel cocky; when they get the idea that they’ve got to lick the world, that’s the time they usually do it.”