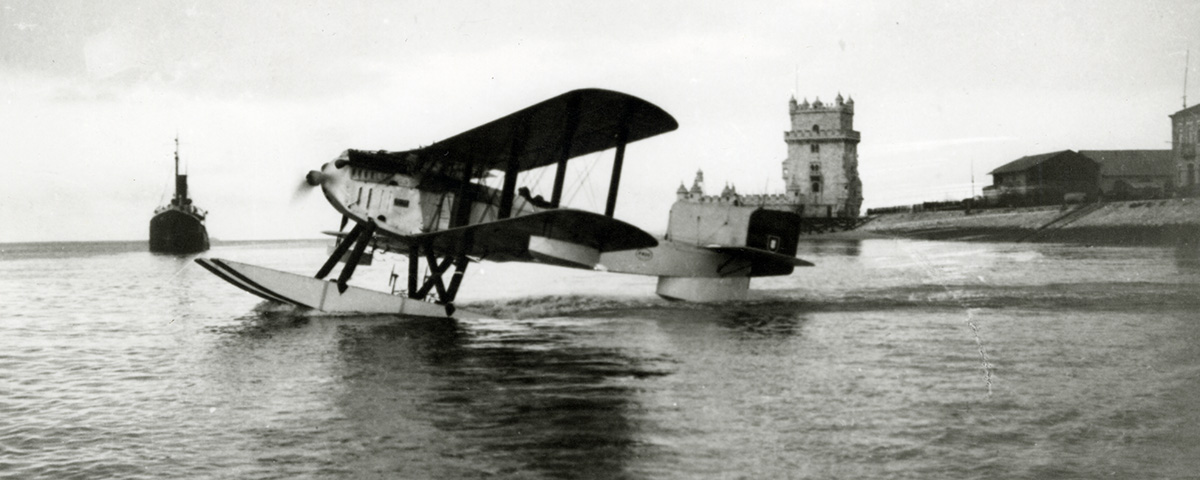

At 0655 hours on March 30, 1922, the heavily laden Fairey IIID floatplane bound for Rio de Janeiro. At the controls in the open cockpit was 40-year-old Portuguese navy Commander Artur de Sacadura Cabral, with Rear Admiral Carlos Viegas Gago Coutinho, 53, as his navigator and occasional copilot. If they reached Rio within one week, the airmen would share a £4,000 Portuguese government prize for the first flight by Portuguese or Brazilian aviators between the two capital cities.

Cabral and Coutinho planned to make the flight in four main stages. The first would take them from Lisbon to the Canary Islands, off the West African coast. From there they would fly to the Cape Verde Islands. The third and most difficult stage would carry them to the Brazilian archipelago of St. Peter and St. Paul Rocks, where a Portuguese warship with refueling facilities would be stationed. Locating this tiny speck in the equatorial ocean would be a supreme test of Coutinho’s navigational abilities. If all went well, the final stage, after reaching the island of Fernando de Noronha and flying down the east coast of Brazil, would land them in Rio— and earn them a place in the record books.

Their British Fairey IIID was a tried and tested floatplane with a record of dependable service in the RAF and Fleet Air Arm. Powered in this instance by a 375-hp Rolls-Royce Eagle engine, it had a top speed of about 106 mph and a normal still-air range of 550 miles. Lusitânia’s wingspan had been extended from 46 to 62 feet and its fuselage lengthened to accommodate extra fuel tanks in the center section. Additional fuel would also be carried in the floats, extracted via wind-driven impeller pumps.

Taking off fully loaded with 330 gallons aboard would require all of Cabral’s skill, as the Fairey’s floats were of a very basic design, with no “step” to induce separation from the water. What’s more, the plywood-covered floats tended to leak.

Coutinho planned to use naval techniques to navigate across the featureless ocean, relying primarily on a specially modified sextant with an artificial horizon of his own invention when the actual horizon was invisible. Smoke bombs would be employed to calculate drift. They were hoping for, but not relying on, help from favorable trade winds on either side of the equator.

The first day went well, with the airmen alighting at Las Palmas, in the Canary Islands, at 1530 hours after covering 900 miles in 8½hours. But then the weather turned against them. It was April 2 before the flight resumed, though storms soon forced them down again into the nearby Bay of Gando.

Two more bad weather days passed before they could continue, heading out across the 800 miles of ocean to St. Vincent in the Cape Verde Islands, which they reached after almost 11 hours. Adverse weather forced them to remain in St. Vincent until April 17, by which time they had exceeded the one-week requirement for the Portuguese government’s prize. On, then, for the short flight to Porto-Praia, another of the Canaries, before heading south the next day on the long transoceanic stage to St. Peter and St. Paul Rocks—assuming they could find them in the vast South Atlantic.

Cabral later described what happened several hours into the flight: “The wind continued to weaken and the fuel consumption remained, at least, around 20 gallons per hour….We must have been about 690 miles from the Rocks and we didn’t have more than eight and a half hours of fuel left. To get there we needed to make 80 miles per hour and our speed was 72 miles per hour. The logical, the prudent thing to do would have been to turn back, but that would have left a bad impression. I confess that for me this was the most bitter part of the Lisbon-Rio trip, because for nine and a half hours I was never sure we had enough fuel to complete the trip.”

Cabral’s doubts proved to be unfounded. After a 1,045-mile, 11 hour 20 minute flight, with their fuel almost exhausted, they located the rocky archipelago. But while alighting on the heavy seas one of Lusitânia’s floats was damaged and the aircraft began to sink. Fortunately their guardian angel, the Portuguese navy sloop Republica, was close at hand to rescue the exhausted airmen. The sloop then took them to Fernando de Noronha to await the arrival of a replacement floatplane that, with national prestige now at stake, was hurriedly shipped from Portugal.

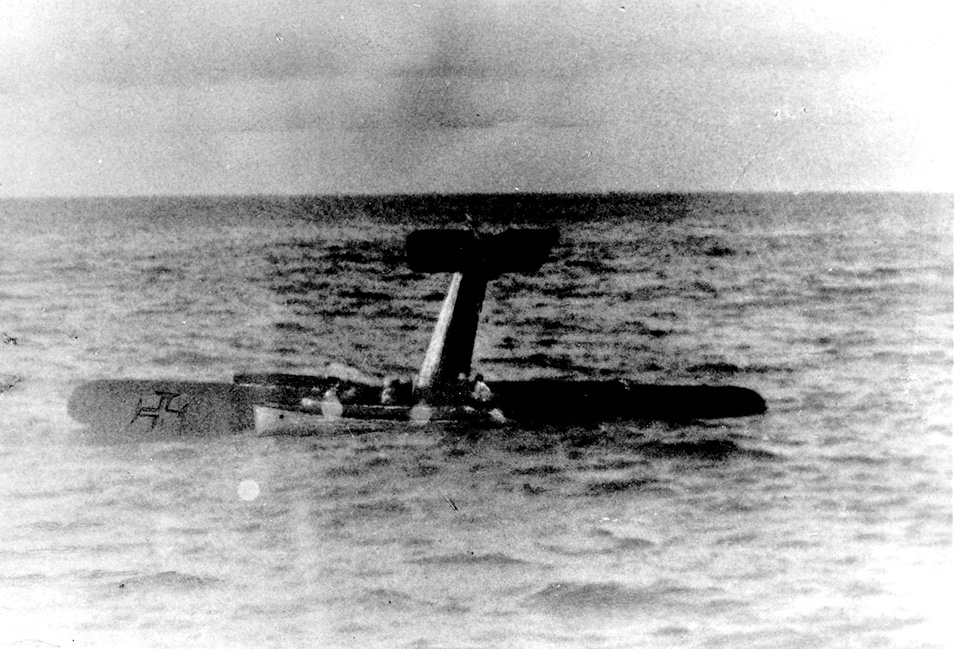

Patria, a slightly modified Fairey IIID, arrived on May 6. Five days later, intent on completing the whole distance, Cabral and Coutinho left Fernando de Noronha and backtracked to St. Peter and St. Paul Rocks—only to run into a major storm that forced them to turn around 15 miles short of the archipelago. While the airmen were battling atrocious conditions on their return to Fernando de Noronha, their engine failed, forcing them to ditch in the ocean. As the floats began taking in water, they were surrounded by a posse of hungry sharks. Fortunately, as Coutinho recalled, “When they realized that the plane wasn’t edible, they went away.”

Meanwhile Republica’s crew had transmitted a wireless distress call requesting all ships in the area to keep an eye out for the missing floatplane. Nine long hours passed before the increasingly desperate airmen were found by the British freighter Paris City, which took them on board and Patria in tow. Next day the freighter rendezvoused with Republica, which tried unsuccessfully to winch the damaged floatplane aboard.

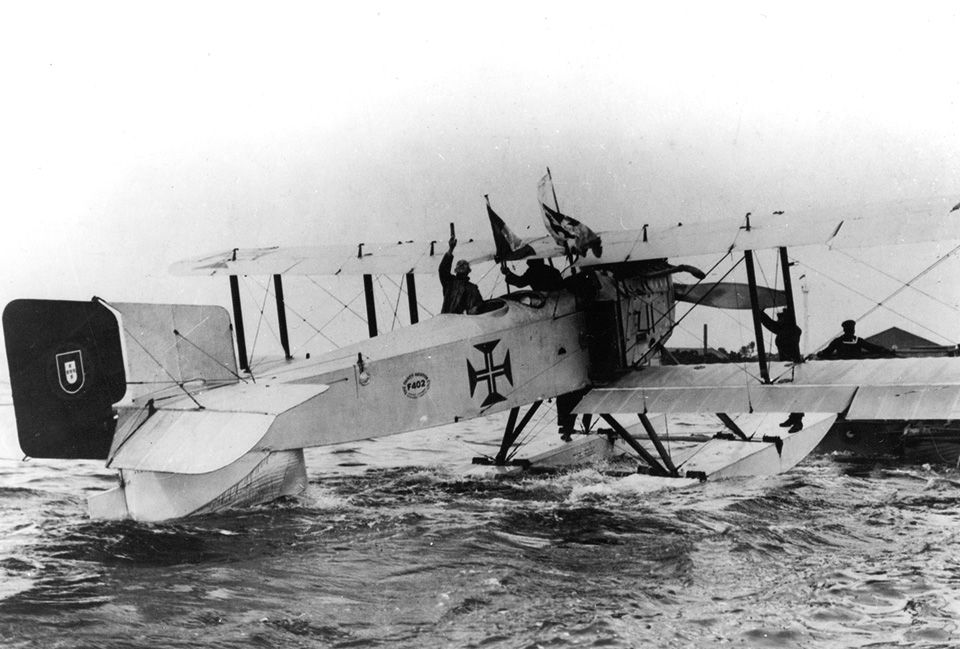

Back yet again at Fernando de Noronha, it was not until June 5 that the indomitable pair resumed their flight, this time in another Fairey IIID, Santa Cruz, sent out on presidential orders aboard a Portuguese warship. By stages they then flew down the east coast of Brazil, via Recife, Salvador de Bahia, Porto Seguro and Vitoria, finally arriving in Rio de Janeiro to a heroes’ welcome on June 17.

In their various aircraft, Cabral and Coutinho had covered some 5,200 miles in 79 days, but with an actual flying time of 62 hours and 26 minutes and an average speed of 83.5 mph. They had completed the first aerial crossing of the South Atlantic Ocean. Moreover, they had also made the first east-to-west crossing of the Atlantic using a heavier-than-air craft. It was a magnificent feat of courage, endeavor and, decisively, navigational expertise.

Britain’s Flight magazine trumpeted: “Our old allies the Portuguese were ever good navigators at sea. They have now proved to be equally to the front in air navigation and we feel proud to think that two British firms have been associated with them in the historical flight to South America.” King George V sent a fulsome message of congratulations to the Portuguese president.

Sacadura Cabral did not survive very long to enjoy his celebrity. In November 1924, Flight reported that the pilot had disappeared over the English Channel while on a delivery flight from Holland to Portugal in the single-engine Fokker floatplane he had intended to use in a round-the-world flight attempt. Although wreckage from the Fokker was found, the bodies of Cabral and his mechanic were never recovered.

As for master navigator Gago Coutinho, he lived on, loaded with honors, until 1959.

Their achievement has been largely forgotten, though not in Portugal. The meticulously restored Santa Cruz, which carried the airmen on the final phase of their flight, is now on display at the Museo de Marinha in Lisbon. There is also a commemorative full-size replica of a Fairey IIID floatplane close to the waterfront of the Tagus River, where it all began.

Frequent contributor Derek O’Connor writes from Amersham, Bucks, UK. For further reading, he recommends: Through Atlantic Clouds, by Clifford Collinson and Captain F. McDermott; and The 91 Before Lindbergh, by Peter Christopher Allen.

Originally published in the May 2015 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.