Henry Ford rarely gets mentioned these days in connection with the history of aviation. A handful of Ford Tri-Motors, most of them on static display in museums, are seemingly all that remain to remind us of Ford’s influence on the development of commercial aviation at a critical juncture. But thanks to his Model T automobile’s longstanding reputation for reliability, in the 1920s the general public saw Ford’s venture into aircraft design and manufacturing as a signpost pointing the way to a time when flying would actually be safe.

Born in 1863, Henry Ford became interested in all kinds of machinery as a young adult. In 1896 he completed his first “horseless carriage,” a four-wheeled buggy frame with a 4-cycle engine that he called a “Quadricycle.” Ford thought big almost from the outset. When he formed the Ford Motor Company in June 1903, he pledged, “I will build a motor car for the great multitude.”

The first Model T rolled out of his factory in October 1908. Ford conceived and perfected a system of a constantly moving production line that by 1914 turned out an automobile every 93 minutes, and by 1918 half the cars in the United States were Model Ts. During the next two decades nearly 17 million of them were sold at a price within reach of the average American family.

But Ford the innovator had other interests besides automobiles—one of which was manifested in 1909, when he helped his only son Edsel install a Model T engine in a copy of a Blériot XI. The plane was unsuccessful, but the Ford Motor Company, along with other auto manufacturers, went on to build nearly 4,000 8- and 12-cylinder Liberty engines after the United States entered World War I. Ford’s major contribution to that effort was to reduce the cost of the engines by solving a serious problem with bearings in the crankcases and connecting rods. In addition, Ford engineers also developed a 2-cylinder, 40-hp engine that could be mass-produced for $40 each to power the secret Kettering Bug, an unmanned flying bomb with a 200-pound warhead.

Ford also saw promise in dirigibles, noting Germany’s success with them and their potential to carry passengers and great amounts of freight. In 1920 he notified the War Department that he could build an Army airship, its engines and a large hangar “without a cent of money to be paid until the craft is finished and accepted.” His offer was ignored.

Undaunted, Ford kept an eye on airship developments. After German Zeppelin pilot Hugo Eckener visited Detroit in 1924, Ford built a mooring mast. The only private dirigible mooring mast in the world, it was equipped with a unique feature: a system that allowed an airship fastened to it to rotate freely to face the wind and permit safer handling in any wind conditions.

Edsel Ford invested in the Stout Metal Airplane Company, owned by William B. Stout, who designed and produced all-metal planes, beginning with the four-passenger, single-engine Stout 1-AS Air Sedan. It was followed by the 2-AT Air Pullman, the first eight-passenger high-wing, single-engine monoplane, and the direct ancestor of the Ford Tri-Motors. The Air Pullman would lead to the 3-AT, Ford’s first three-engine aircraft.

Henry Ford agreed with his son that their company should become more involved in helping to develop commercial aviation. One of the great needs they perceived was for more U.S. airfields. In 1925 Ford Airport was laid out in farmland near the Ford headquarters at Dearborn, Mich. In addition, the Fords built a large facility where Stout continued his development work on all-metal aircraft. The name “FORD” was spelled out in 200-foot letters with white crushed stone so that pilots could more easily identify the airport from the air. Later, large floodlights and a revolving beacon light were also installed.

At first the airport was widely praised as one of the best in the world, but it soon needed improvement, since the tail skids on most aircraft of the day tore up the sod fields. In December 1928, Ford Airport got the first concrete runway in the world. That was soon followed by a passenger terminal, a weather station and the Dearborn Inn for transient travelers—all of which became models for other airport developers.

As public interest in aviation increased after WWI, so did Henry Ford’s awareness of commercial aviation’s potential for carrying large numbers of passengers. He purchased the stock and assets of the Stout Metal Airplane Co., which became a division of the Ford Motor Co. in July 1925. The airport facilities were then dedicated to the further development and production of trimotor planes. Ford News announced that acquisition of the company was made “for the purpose of accelerating airplane development by backing the [trimotor] design with the diversified resources and experience of the Ford organization.”

Ford used the first trimotor transports built at the new factory to establish the Ford Air Transportation Service in April 1925, carrying company mail and freight on scheduled flights between Dearborn and the U.S. Air Mail field near Chicago, Il. Thus began the first air transportation service operated for the benefit of a commercial company and the first air freight service to maintain a regular schedule. A second route was established in 1926 linking the headquarters with the company’s operations in Cleveland, and service was ex – tended to Buffalo in 1927. By that time more than 1,000 successful flights had been made, with payloads of up to 1,500 pounds per flight. The Ford Air Transportation Service continued to do business until August 1932.

When private operators began taking over mail routes from the U.S. Post Office Department in 1926, Ford was the first company awarded a contract to fly the mail between Detroit, Chicago and Cleveland. According to C.M. Keys, president of the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Co., Ford’s operations represented “the starting point of organized commercial aviation in this country.” Keys also pointed out that Ford’s operating experience was truly public-spirited and offered without charge to other operators. An editorial in a Detroit newspaper commented, “Ford’s entrance into aviation means progress in three departments: commercial flying, passenger flying, and national defense.”

After Ford purchased Stout’s assets, he announced plans to begin building planes at the rate of one every two weeks—possible, he said, because he would apply the Ford system of progressive production of automobiles to aircraft manufacturing for the first time. A larger factory was built to turn out the ubiquitous Ford Tri-Motors—4-AT and 5-AT models that were sold to the burgeoning airlines—and production was increased within three years to one plane every other day. The U.S. Army, Navy and Marine Corps also purchased Ford Tri-Motors for use as transports, with one modified as an air ambulance. Ford also produced a bomber, designated the XB-906, but its design was judged unsatisfactory, so it never received a government contract.

Pilot Bernt Balchen’s 1928 flight to the South Pole in a 4-AT, with U.S. Navy Rear Adm. Richard E. Byrd as an observer, became one of the Ford Tri-Motor’s crowning moments. That same year Balchen flew a 4-AT to rescue the three crewmen of Bremen, a German Junkers W33L monoplane forced down on Greenly Island, Newfoundland, at the end of the first east-west transatlantic flight.

The years 1928 and 1929 were a prime production period for Ford Tri-Motors. Some experimental configurations were tried— one with floats, another on skis and one with two of the three engines mounted within the wings instead of hanging beneath. In an attempt to prove that three engines were not actually needed, a 5-AT was modified with a single nose-mounted engine to produce the 8-AT Freighter, but it was the only one built.

By that time Ford had come to believe that aircraft manufacturers should develop planes with greater passenger capacity, so he asked Stout to design a transport capable of carrying an unheard-of 100 passengers. Stout cautioned Ford that such a large plane was not feasible at the time, explaining that it would be much more practical to build a smaller one first. Ford reportedly replied, “No, I would rather build a big plane and learn something, even if it didn’t fly, than to build a smaller one that worked perfectly and not learn anything.”

Ford eventually yielded to Stout’s logic, and instead of a giant transport, Stout designed the 10-A, a 32-passenger, four-engine plane with compartments like Pullman railroad cars. It was to be powered by two 575-hp Pratt & Whitney Hornet engines mounted in the wings and a tractor-pusher combination on top of the center section. Although the 10-A was never built, it evolved into the 12-A (also not built), which in turn served as the basis for the 14-A. Constructed in 1932 at an estimated cost of more than $1 million, the 14-A had seats for 32 passengers, a smoking room, two lavatories and a galley. It collapsed during taxi tests, however, and never flew—marking the end of the Ford Tri-Motor line. Other Tri-Motor models included the 6-AT, 7-AT, 9-AT, 11-AT and 13-A, all modified 4- and 5-AT airframes equipped with different engines.

In the interim years, Stout had designed other aircraft, including a twin-engine, tandem-wing amphibian that made one flight in 1928 and crashed. A five-seat, single-engine monoplane that Ford thought might fulfill the need for an executive transport was also constructed. But it was so tail-heavy that after its only flight Ford test pilot Edward G. Hamilton commented, “I think you should run a band saw through it before you kill somebody.”

At this point Ford recognized the technological leap that Douglas was making with its twin-engine DC-2s and DC-3s and Boeing with its 247s. With the Great Depression in full flower, he decided that the trimotor era was over. He would subsequently concentrate full time on automobile production to keep his company alive.

Before the Depression gripped the country, Ford had launched an initiative that helped the aviation industry at a critical time. Harvey Campbell of the Detroit Board of Commerce had proposed an air tour patterned after the Glidden Auto Tours initiated in 1904 to gain public acceptance of the automobile. Henry Ford adopted the idea, and Edsel organized the Ford air tours in 1925 “to stimulate interest among civilian constructors and pilots” and “to end the dominance of the military and the emphasis on thrills and stunt flying, [as well as] demonstrate the reliability of travel by air on a predetermined schedule regardless of intermediate ground facilities.” Cash prizes and a large gold and silver Edsel B. Ford Reliability Trophy were donated “to encourage the up-building of commercial aviation as a medium of transportation” and help erase aviation’s reckless image.

Requirements for participation in the tours stipulated that aircraft had to seat at least one passenger and provide at least eight cubic feet of cargo space. The planes had to be capable of 80 mph, and a formula was devised to award points for speed on each leg along the air tour route. There were rules for reliability, loads carried and multiengine differences, all calculated to arrive at a “Figure of Merit” to decide the winners.

Seventeen models from 11 manufacturers qualified, mostly single-engine types, including a Stout 2-AT and a Junkers F13L. Dutch-born Anthony Fokker entered his Fokker F.VIIA trimotor. All entries were to depart from Ford Airport in Dearborn, make stops at 12 cities in the Midwest and return from the 1,775-mile flights within six days.

Recommended for you

The first air tour began on September 28, 1925, and there were several minor accidents and forced landings due to bad weather. Fokker was determined to show off his six-passenger, wooden-winged, fabric-covered trimotor—which on this occasion carried seven passengers. He refused to land the heavy plane on several muddy fields, however, making an overhead fly-by at each one before continuing to the next stop. He and 10 other entrants received silver medals and $350 each, while four others who finished by sundown on the final day each received $125. The last air tour was in 1931 and covered 4,818 miles with 33 stops. The total prize money raised by Ford dealers to bring the event to their cities had increased to more than $15,000 by that time, but no funds could be raised for a tour in 1932 because of the Depression.

Overall statistics for the seven tours showed that Waco biplanes led the 142 competing planes with 17 entries, winning two firsts and two second places. Second in number of awards were the Ford Tri-Motors and single-engine Stouts, with nine entries, two firsts, two seconds and a total of over $13,000 in prizes. The tours attracted thousands of spectators at each stop and did much to promote public confidence in private and commercial aircraft.

One of the side benefits of the air tours was a program to encourage Ford automobile dealers along the tour routes to paint the names of their cities on the roofs of their facilities, along with an arrow pointing due north (the arrows were later repainted to point to the nearest airport). That concept was further promoted by the Guggenheim Foundation and later adopted in a Department of Commerce program. By the end of 1929, about 6,000 U.S. communities had painted town identification signs on rooftops and water towers.

The idea of a single-engine personal plane with only one seat captured Edsel Ford’s imagination after Lawrence Sperry, son of the gyroscope inventor, landed on the Ford estate lawn one day in 1923 in his single-seat Sperry Messenger biplane. Edsel commented that just as his father had managed to sell the public on automobiles, “We ought to be able to sell ‘airplane flivvers’ to the same type of individuals—to pioneers who are going to break unbroken ground and fly, despite all obstacles.”

“Flivver” had become the common nickname for the Ford Model T, and Edsel decided to use it for his plane, which was designed by Otto Koppen, an MIT graduate. The basic model of a single-seat private aircraft became Ford Flivver No. 1. First flown on June 8, 1926, it was promptly hailed by the press as the “Model T of the Air.” Weighing 350 pounds, it was powered by a 3-cylinder, 35-hp Anzani engine. Flivver No. 2 had a 35-hp, 2-cylinder Ford engine installed. Its top speed was calculated at 85 mph.

In an era when aviation speed and distance records were being broken daily, Flivver No. 3—slightly larger than the other two—was designed to break the world distance record for lightplanes, which then stood at 870 miles. Ford’s favorite test pilot, 25-year-old Harry Brooks, departed Dearborn in January 1928 for Miami, Fla. After only nine hours in the air he was forced down at Emma, N.C., by rough weather and icing. He returned to Dearborn and tried again the next month, this time making it as far as Titusville, Fla., where he managed to land on the beach after discovering a fuel leak. He received credit for having set a new nonstop record of 972 miles for that type of aircraft. Just four days later, however, when he attempted to resume his flight to Miami, he disappeared over the Atlantic Ocean. His body was never found.

The Fords were greatly saddened by Brooks’ death, and production of the Flivvers was suspended. But Edsel’s interest in small planes was reenergized in November 1933 when Eugene Vidal, director of the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Aeronautics, encouraged the aircraft industry to produce 10,000 low-priced planes and “democratize” aviation by developing it for the multitudes.

Vidal’s hope was that “the New Deal may do for the airplane what the pioneers of mass production did for the automobile: Convert it from a rich man’s hobby to a daily utility or inexpensive pleasure for the average American citizen.” Vidal envisioned an all-metal aircraft built of steel alloy, equipped with two seats, an 8-cylinder engine and a geared propeller. It should have a landing speed of only 25 mph and cost $700.

After a consultation with Ford engineers, Vidal concluded this was a reasonable estimate, especially when Ford announced it could produce a small V-8 engine for $65 if 10,000 planes were built. It seemed an ill-timed proposal in the middle of the Depression, but Edsel nevertheless informed Vidal that the company was experimenting with its V-8 engines for use in aircraft, and a full-size mock-up of the plane had already been completed.

Designated the 15-P, the prototype was a strange-looking flying wing trainer that seated two people side by side. It featured steel tubing construction with fabric-covered wings, an aluminum alloy fuselage and a Ford V-8 aluminum engine with an exceptionally long propeller. Timothy J. O’Callaghan, a retired Ford executive and author of two books on the company’s aviation ventures, described how the 15-P was controlled: “The occupants were seated at the center of gravity and longitudinal control was activated by shifting their weight forward or backward. Lateral control was by conventional ailerons, and yawing was controlled by split rudders attached to the trailing edge of the wing tips adjacent to the ailerons. As can be imagined, control of the plane was difficult and the strong torque of the large propeller only made it more so. There was plenty of lift to get it off the ground but in spite of everything they could think of, they couldn’t control its tendency to turn.” After several short test flights, it was involved in an accident and destroyed.

Despite their disappointments with building small planes, the Fords continued promoting commercial aviation. They placed advertisements for Ford Tri-Motors in major newspapers and magazines that stressed the safety, comfort and reliability of modern aircraft when they were flown by responsible pilots. An editorial in Aero Digest claimed that Ford’s advertising had “done more to popularize flying among the reading public than all the stunts that have ever been stunted.”

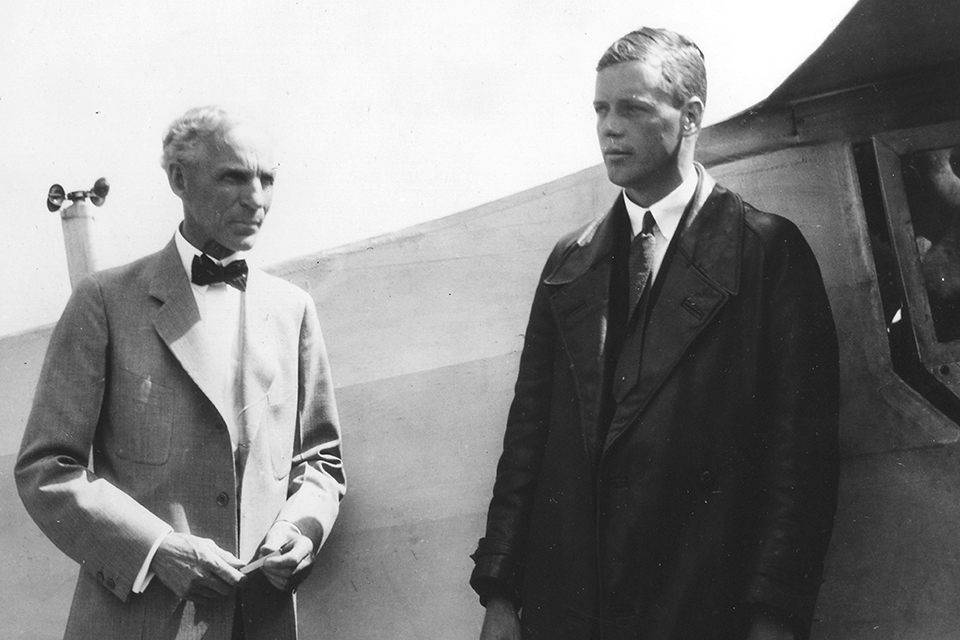

Charles A. Lindbergh visited Ford Airport with Spirit of St. Louis during a promotional tour after his epic flight in May 1927. Although the Fords were promoting commercial aviation at every opportunity, up to that time Henry Ford himself had steadfastly refused to fly in any type of airplane. Lindbergh, “as a matter of politeness,” invited Henry to fly with him, sure he would decline. This time, however, to Lindy’s surprise the elder Ford accepted.

“The Ford men standing around us looked astounded,” Lindbergh wrote in Autobiography of Values, “but of course no one questioned the wisdom of Mr. Ford’s decision—at least not in words. My cockpit had been designed to fit snugly around one slender man of six feet two and a half inches of height. It was possible for another person to sit hunched up on the armrest of the pilot’s seat; but that was a most uncomfortable position, and it forced me to lean awkwardly to the left side of the fuselage to make room. In the Spirit of St. Louis, bent over, cramped, and delighted, Henry Ford made his first flight in an airplane.”

Lindbergh took Henry on a 10-minute flight over Dearborn, then Edsel went up on his own first flight. Both Fords then accompanied Lindbergh on his first flight in a new Ford Tri-Motor. Lindbergh next flew a Flivver and remarked, “That gives you a real sensation of flying that you can’t get in one of the larger planes.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Lindbergh later said he was impressed with the elder Ford, this “mythical character who had become one of the world’s richest men…who was so powerful in the business world that he could make a success of almost anything he decided to support. The genius of Henry Ford did not depend much on logic for his business ventures. Intuition played a major part in his phenomenal success….The Ford Motor Co. maintained a tradition of action. Men who did not take action did not hold their jobs very long, and everybody who worked for the company was well aware of it.”

The Depression affected Ford adversely, as it did all auto and plane manufacturers. The last of 212 Stout/Ford aircraft built were two Ford Tri-Motors delivered to Pan American Airways in May 1933.

Adolf Hitler’s march into Poland in 1939 changed the focus of industrialists worldwide. Henry Ford, who hated war, quickly restructured the company to help aviation once more, as he had done during World War I. It was no secret that he was an inveterate critic of “Roosevelt’s War.” He was vilified in the press for his pacifist views, but the company accepted contracts to produce war materiel for Great Britain and France beginning in 1940. Ford directed the construction of the world’s largest factory, with 5 million square feet of space, at Willow Run near Ypsilanti, Mich., to produce Consolidated B-24 Liberators.

The workers soon found that there was a vast difference between turning out automobiles and warplanes on a moving production line. Unlike automobiles, aircraft were subject to continual design changes as the planes experienced the rigors of combat. These in turn led to factory slowdowns. Worker shortages, lack of expertise and inadequate supplies contributed to the problem. Some came to believe that planes were incapable of being mass-produced, and critics started derisively referring to Willow Run as “Will-it-run.”

Ever indomitable, Ford gradually ironed out the problems. Workers were imported from the South, and more women were hired to take the place of men who joined the services. The key to mass production was tooling, and Ford had carried the technique further than any other company in the world with his system of progressive assembly lines. Another key was training, although it was a much more difficult task to train 42,000 workers to construct a four-engine bomber, with more than 150,000 parts, compared to an automobile of the period, with some 15,000 components.

Ford subsequently set an eventual production goal of one B-24 Liberator per hour. By the end of 1942, only 56 acceptable B-24s had been produced at Willow Run, but 11 months later the 1,000th Liberator rolled out. The last of 8,685 Ford-produced B-24s was completed in June 1945, marking the end of the Ford Motor Company’s ventures in aircraft production.

Although the company is perhaps best remembered for that outstanding wartime accomplishment, which set production standards for aircraft manufacturing, Ford also turned out 4,000 Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engines, 4,202 Waco CG-4A Army gliders and 87 of the larger CG-13As. Ford engineers built an advanced altitude chamber for testing equipment and flight personnel at low temperatures and high altitudes. And 2,400 jet engines were assembled to power Army Air Forces and Navy missiles—improved versions of German V-1 buzz bombs—that were intended for use against Japan. Ford also produced hundreds of bomb trucks, airplane drop tanks, aircraft generators and cockpit instruments, and maintained a school to train 50,000 military aircraft maintenance personnel.

Edsel Ford, who had worked for a quarter century alongside his father, did not live to the end of the war. He died on May 26, 1943, at age 54. His father died at 83 on April 7, 1947, having seen the bombers his company produced make a major contribution to defeating the Axis powers.

Although Ford Tri-Motors have won a permanent place in history for their sturdy reliability, Henry Ford did not receive any honors for his aviation contributions during his lifetime. His remarkable accomplishments were finally recognized in 1984 by the National Aviation Hall of Fame, which enshrined him “for outstanding contributions to aviation by his leadership in the development and mass production of commercial and military aircraft and engines.”

It was a tribute long overdue.

For additional reading, contributing editor C.V. Glines recommends The Aviation Legacy of Henry & Edsel Ford, by Timothy J. O’Callaghan.

Originally published in the May 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.