When history travel becomes a reality, visit the small town where the border war got seriously ugly

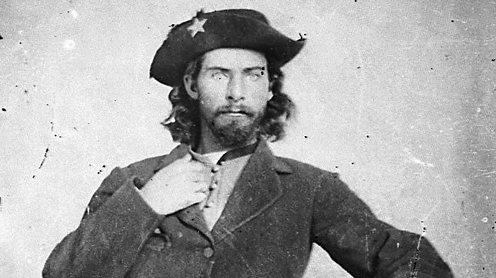

On the morning of September 27, 1864, in the tiny mid-Missouri town of Centralia, about 80 Confederate guerrillas under Captain William T. “Bloody Bill” Anderson carried out a brutal massacre of two dozen Union soldiers.

Later that day, about three miles southeast of town, Anderson and his men, joined there by several hundred other Confederate guerrillas, ambushed and wiped out an entire Union regiment that had been sent to pursue them. These two actions—the Centralia Massacre and the subsequent Battle of Centralia—reveal the guerrillas’ most notable characteristics: their exceptional fighting prowess in mounted combat and their absolute ruthlessness.

By the fall of 1864, the Civil War in Missouri had degenerated into a no-quarter struggle between the Union forces that had, in effect, occupied the strategically important border state since 1861 and highly mobile bands of Confederate guerrillas. Missouri’s population was divided: some were staunchly pro-Union; others rabidly pro-Confederate; and many simply wanted to be left alone—a largely untenable position when Union troops or Confederate guerrillas arrived at their farms or towns. The result was a horrific conflict in which the two sides exhibited a hatred for each other that is difficult to comprehend 150 years later. Atrocity begat atrocity: On August 21, 1863, Confederate guerrillas under William C. Quantrill burned Lawrence, Kan., killing 150 men and boys; four days later, Union commander Maj. Gen. Thomas Ewing issued his draconian Order No. 11, prompting the violent evacuation—today we’d call it “ethnic cleansing”—of four western Missouri counties, turning them into what became known as the “Burnt District.” Both sides routinely executed prisoners, scalped and mutilated fallen foes, murdered civilians, confiscated property and livestock, and burned homes, farms and public buildings. When “Bloody Bill” Anderson’s guerrillas arrived in Centralia around 9 a.m. that Tuesday, the town’s 100 residents knew enough to stay out of sight and hope for the best.

CENTRALIA MASSACRE

Anderson’s men looted the town’s stores and some homes, and blocked the tracks of the North Missouri Railroad with piles of railroad ties. This obstacle soon halted a westbound train out of St. Louis whose 125 passengers included two dozen Union soldiers, unarmed while traveling home on leave after Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign. Guerrillas ordered the Union soldiers to strip and Anderson called for the men’s commander. Sergeant Thomas Goodman stepped forward and Anderson took him prisoner, presumably to exchange him later for a captured guerrilla (10 days later Goodman successfully escaped). Within moments, guerrillas shot dead all of Goodman’s comrades, some of whom were scalped and their bodies mutilated. The guerrillas burned the train depot and destroyed the train by setting fire to it and sending it chugging crewless west along the tracks. Anderson then remounted his men and led them southeast out of Centralia.

BATTLE OF CENTRALIA

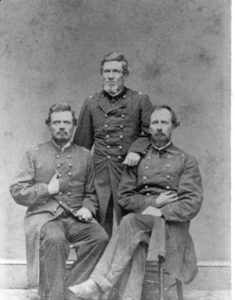

About 3 p.m., Union Major Andrew V.E. Johnston arrived in Centralia at the head of about 155 men of the 39th Missouri Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the infantrymen mounted on plodding farm horses, hardly a match for proper cavalry mounts. Although warned by townsfolk that Anderson had at least 80 well-armed men—and that hundreds more guerrillas were thought to be in the area—Johnston nevertheless left about 30 soldiers in the town and led the rest cross-country southeast in pursuit of the Confederate guerrillas. Just over three miles south of Centralia, in an open field surrounded on three sides by thick timber bordering a wide loop of Young’s Creek, Johnston’s command found Anderson’s men.

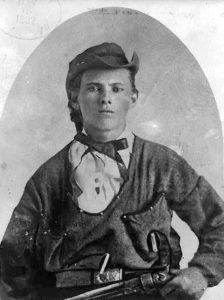

Trained to fight as infantrymen—their plough-horse mounts were only for mobility—the 39th Infantry soldiers dismounted and were formed into a line of battle. Soon after, Anderson’s guerrillas, each man well-armed with several six-shot revolvers, burst out of the tree line at a gallop. Johnston’s infantrymen fired one ragged, largely ineffective volley with their single-shot Enfield rifle-muskets but had no time to reload before the guerrillas overran the Union battle line, shooting Johnston’s men down with their rapid-firing pistols. Meanwhile, from the timber to Johnston’s right and left, hundreds more guerrillas charged the disintegrating Union line. Panicked Union soldiers tried to flee but the guerrillas, well-mounted on vastly superior horseflesh, quickly rode them down. Only a handful of Johnston’s men escaped, leaving the mutilated bodies of 123 of their comrades on the battlefield. The battle lasted perhaps three minutes and as few as only three guerrillas were killed. Frank James, one of Anderson’s band, later claimed that his 17-year-old brother Jesse fired the bullet that killed Major Johnston.

AFTERMATH

In retaliation for the Centralia raid, Union forces burned Rocheport, Mo., to the ground, killing many civilians merely suspected of “harboring” guerrillas. The Union force occupying Missouri also intensified efforts to track down and kill “Bloody Bill.” Anderson survived Centralia less than a month, being shot dead in a Union militia ambush near Orrick, Mo., about 120 miles west of Centralia, on October 26, 1864. His killers decapitated his corpse and displayed his severed head on a post.

HOW TO GET THERE WHEN YOU CAN GET THERE

While the Covid-19 pandemic has affected many businesses and restaurants in Centralia, it’s worth putting the sleepy farming town of about 4,000 on your travel bucket list for the future. It is less than 20 miles north of Interstate 70, the major east-west artery linking St. Louis and Kansas City. Take Exit 133 and follow Route Z north to Centralia. Interpretive markers and monuments in the town square and at the battlefield explain the massacre and battle. To learn more, visit centraliabattlefield.com

Massacre Site:

On Railroad Street between Rollins and Allen Streets

Battle Site (3.5 miles southeast of Centralia):

Proceed south on Jefferson St. (Route Z); turn left on E. Gano Chance Dr. (Route JJ); turn sharply right and road becomes N. Rangeline Rd. (County Road 997) to battlefield.

NEARBY ATTRACTIONS

The National Churchill Museum (nationalchurchillmuseum.org) at Westminster College, Fulton, Mo., is a major Cold War landmark—the site of Winston Churchill’s famed 1946 Iron Curtain speech. The state-of-the-art museum is in the undercroft of the Church of St. Mary Aldermanbury, a 17th-century Christopher Wren church damaged during the WWII Blitz. The church’s remains were moved to Fulton in the late 1960s and restored to its original magnificence. It has been hailed as the most authentic Wren church in existence. Fulton is about 42 miles southeast of Centralia via 1-70 East and US 54.

WHERE TO STAY

Columbia, about 22 miles southwest (via MO 124, N Route B/Paris Rd) and home of the University of Missouri, has dozens of hotels. We recommend: The historic Tiger Hotel (thetigerhotel.com), a 4-star luxury boutique hotel, 23 South Eighth St. When built in 1928, it was the first “skyscraper” between Kansas City and St. Louis.

WHERE TO EAT & DRINK

Restaurants and cafes also abound in Columbia (think of all those hungry, thirsty MU students). We recommend: Broadway Brewery (broadwaybrewery.com), 816 E. Broadway, which is open for pickup and curbside delivery. The menu features a variety of “pub food” of locally grown/raised produce, and—best of all—over two dozen house-crafted ales, stouts, porters and cider.

Among the beer selections is Flor Blanca, a Mexican-style lager brewed with flaked corn and a touch of Flor Blanca Mexican sea salt. This beer begs to be drunk with a lime to welcome in the warmer weather!

This story from America’s Civil War was posted on Historynet.com on April 28, 2020.