Boredom as a feature of military life can yield interesting outcomes. For a B-17 crew of the U.S. Eighth Air Force waylaid in North Africa in 1943, the quest for distraction led to the acquisition of World War II’s quirkiest mascot: Lady Moe, the cigarette-eating donkey.

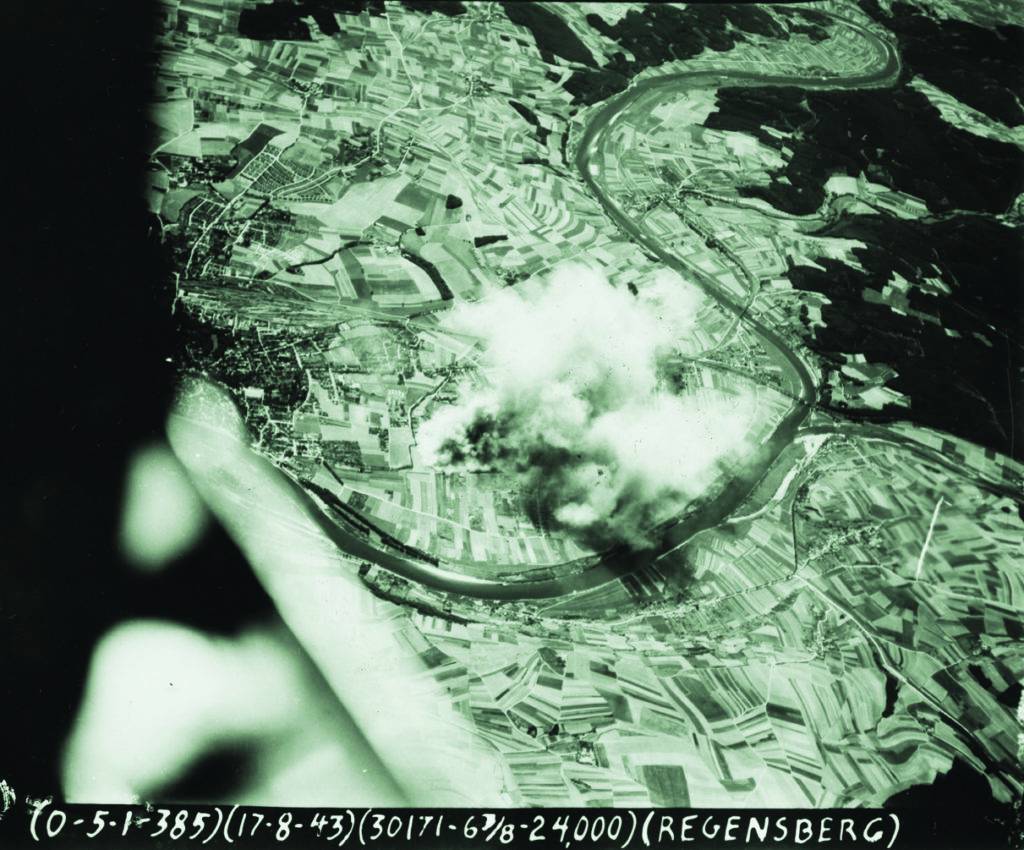

From dogs and cats to more unconventional creatures like monkeys and parrots, animal mascots have long been part and parcel of military life. Few, though, can claim an origin story quite like Lady Moe’s, whose odyssey from North Africa to the United Kingdom began as high strategy. In August 1943, the U.S. Army Air Forces planned to send the Eighth Air Force’s heavy bombers to two targets in southern Germany, an undertaking known as the Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission—the first major U.S. deep penetration strategic bombing raid. One force would return to England after bombing Schweinfurt’s ball bearing factories; the other would strike the Messerschmitt fighter plant at Regensburg and then continue to North Africa, bomb up, refuel, and return, hitting the Bordeaux-Merignac airfield in occupied France on the way back.

While the initial strategy looked great on paper, execution ultimately left something to be desired. The target cities were both successfully hit, but at a cost: 60 Eighth Air Force bombers were shot down, with many more heavily damaged. The weakened Regensburg task force flew on as planned to North Africa, only to find insufficient spare parts and maintenance facilities; just 60 of the 115 B-17 Flying Fortresses that made it to Algeria were deemed airworthy for the return strike on Bordeaux-Merignac. On top of this, dismal weather delayed their return for five days, leaving a bunch of airmen at loose ends—including the crew of a B-17 with the 96th Bomb Group whose name, “The Miracle Tribe,” was an homage to its pilot, Second Lieutenant Andrew Miracle.

During this hiatus, Miracle Tribe member and ball turret gunner Lou Klimchak suggested a mascot might be a good idea—something besides the usual dog. There was the typical joking. Being in North Africa, a camel naturally came to mind, but the airmen couldn’t figure out a way to fit a camel, even a small one, into a B-17. A veiled Arab maiden was considered and vetoed on the consensus that taking one might be considered kidnapping. A young Algerian lurking around the airfield overheard the conversation and mentioned that his family had a donkey that might be for sale, so Klimchak and Miracle Tribe copilot Jim Harris went to the boy’s home to take a look. There they were greeted by donkeys, a few goats, scrawny chickens, a cow, and several people. Moe was perhaps the sorriest member of the household, Harris recalled.

“She was about two feet tall, weighed about 50 pounds, and looked like she was about to starve to death,” he said.

Haggling over Moe began at 800 Algerian francs, or about $16. The final price was 400 francs. The sale complete, the two took Moe away to begin her new life as sort of a hairy Ava Gardner, destined to hobnob with royalty and find herself in the pages of Time.

She also became the first—and possibly only—one of her kind to successfully fly a combat mission with the U.S. Army Air Forces. On the way to hit Bordeaux-Merignac before the return to England, the airmen installed Moe in the bomber’s radio room, fitted with a jury-rigged oxygen mask and wrapped in all the blankets the crew could scrounge together. She arrived safely, although a second donkey acquired by another crew on the mission wasn’t so lucky; it succumbed to the altitude and cold (or perhaps simple fright) and was dumped with the bombs on what must have been a startled Bordeaux.

The 96th Bomb Group’s public information officer made a big deal of Lady Moe’s arrival; one memorable portrait shows her peering out of a B-17’s right waist window with both Klimchak and waist gunner Ed “Coots” Matthews looking on. Unfortunately, the publicity also attracted the attention of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, which insisted that Lady Moe be returned to her ancestral home immediately. Objections to her presence faded when Matthews pointed out that the society would have to foot the bill for her transportation since no 96th B-17s were likely to be returning to North Africa anytime soon. In an ironic twist, Lady Moe was later a celebrity guest at a fundraiser for the RSPCA. She met the Queen Mother and helped raise $1,600.

Lady Moe settled in quickly at the airbase at Snetterton Heath, the 96th Bomb Group’s home in Norfolk, England. Provided with a deluxe straw-lined squad tent, the donkey preferred the free and easy life of mooching, according to 96th bombardier [and the author’s father] Fred Huston; she found human quarters more to her taste than her lonely abode.

“You had to check your bunk for anything furry after a quiet night at the club,” he said. “It took a lot of cussin’ and kickin’ to move a comfortable Moe.”

Lady Moe knew what time meals were served and could predictably be found waiting at the doors of the mess halls for handouts. Unfortunately, a lack of respect for rank caused her to be banished from the officer’s mess. It was her custom, Huston said, to stick her nose into everyone’s plates to see if there was anything good. But the morning she stuck her nose into the group commanding officer’s plate she went too far, and thenceforward had to wait outside. (Huston said Lady Moe got her revenge by nosing the CO’s two Dalmatians into the firefighting lagoon as they were taking a drink.) On post exchange day, when one might be expected to find something besides razor blades at the airbase’s army-operated convenience store, there she would be, Huston said, “stretching her neck and making pitiful, hungry donkey noises and doing her best to get in on whatever goodies might be at hand.”

Lady Moe “was even known to eat Ping bars [a tooth-achingly sugary Mars product made of sweet chocolate, coconut, walnuts, and corn syrup], which were pretty much inedible,” he said. “If you didn’t feed her, she would advertise the fact loudly. She would eat anything—cigarettes, preferably, or anything with sugar in it.” Lady Moe had no brand preference when it came to cigarettes, Huston added; she’d eat any coffin nail offered to her.

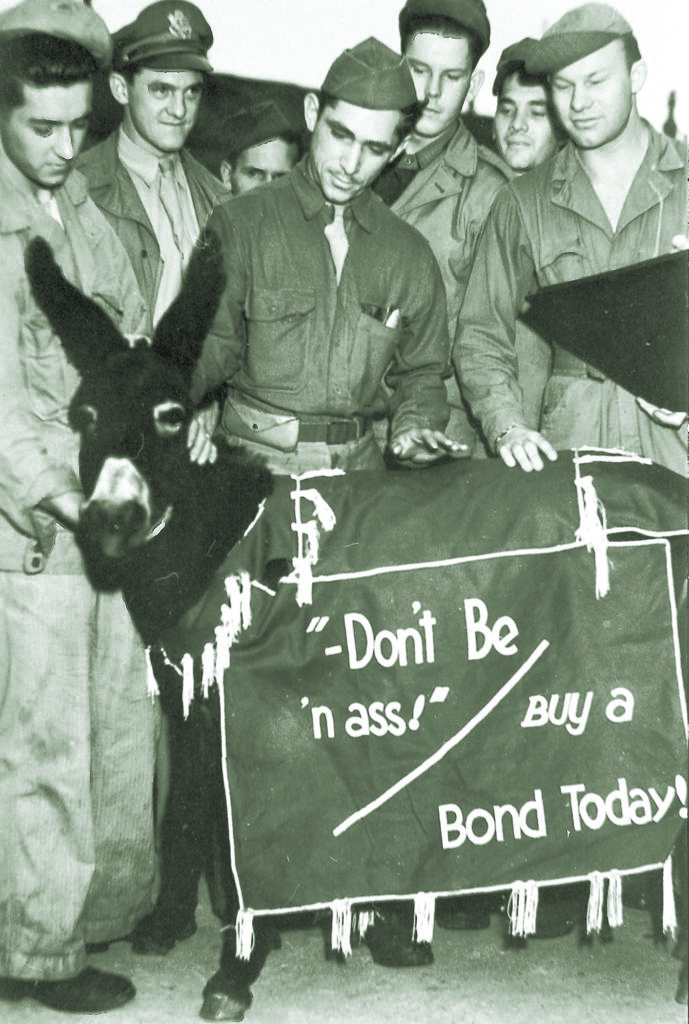

Naturally, Lady Moe was the star of nearly every event on the base. At Christmas, she was adorned with antlers to become a reindeer at a party for English orphans. She had her own red-and-gold bond-drive blanket for payday appearances. For a reason not recorded, she once appeared in front of the officers’ mess painted in bright green-and-white vertical stripes—a sight, Huston said, that made one want to give up strong drink.

Celebrity came with a price. A feature in the December 27, 1943, issue of Time magazine included the unkind quip, “Probably the most photographed member of a heavy bomber squadron in the Eighth Air Force is not a pilot, but a grotesque little North African donkey. Her name: Lady Moe.” And while she was beloved by Snetterton Heath’s bombardiers, the group public information officer complained that he had joined the army to serve his country, not be a valet to a jackass. His responsibilities included answering the donkey’s fan mail and escorting her to her many public appearances.

Lady Moe survived the war. Her fate shortly after that is less certain. Some 96th Bomb Group veterans insist a local farmer adopted her. But it’s more likely that Lady Moe, accustomed to wandering freely around Snetterton Heath, trotted in front of a London and Northeastern train in October 1945—a grim end supported by newspaper and military accounts. At any rate, her fame as an Eighth Air Force mascot is everlasting, enough so that an unrelated Texas donkey acquired in the late 1950s by the 338th Bomb Squadron, 96th Bomb Wing, at Dyess Air Force Base near Abilene, was dubbed “Lady Moe II.” ✯