On the cold, flint-gray morning of November 29, 1872, as sleet drummed the frozen earth, 37 troopers of Company B, 1st U.S. Cavalry, entered a camp of nearly 200 Modoc Indians on the Lost River near where it flows into Tule Lake, along the California-Oregon border. Leading the force was Captain James Jackson, who had orders to return the Modocs to their homes in Oregon’s Klamath Indian Reservation. Modocs weren’t likely to go quietly. After clashes on the reservation

The with the Klamath tribe, a longtime enemy, they had returned to the Lost River region where their ancestors had lived and hunted for decades. Now, alarmed by Captain Jackson and his men, warriors stumbled from their lodges to confront the troopers. Chikclikam Lipolkuelatk, a Modoc war leader called Scarfaced Charley by white settlers, ordered the soldiers to leave, then distributed rifles to his men. Inside his lodge, the Modoc chief, Kientpoos, hurriedly dressed.

“What do you think of the situation?” Jackson asked his second in command, Lieutenant Frazier Boutelle. “There is going to be a fight,” the lieutenant warned, “and the sooner you open it the better.”

Jackson told Boutelle to arrest Scarfaced Charley. Boutelle leveled his pistol at the Modoc leader, demanded his gun, and barked, “You son of a bitch.” Charley raised his rifle in reply. The two fired but missed. Then everyone began shooting.

The fighting was over in five minutes. Eight soldiers and one Modoc were killed. When the smoke from the gunfire lifted, the Indians were gone, paddling their canoes hard across Tule Lake. Reaching shore, they took refuge in the Lava Beds, a rugged desert area of caves, boulders, and rock formed by volcanoes thousands of years ago.

The stage was set for a six-month struggle that ranks among the most humiliating U.S. Army campaigns of the Indian Wars. The Modoc force consisted of just 57 warriors armed only with single-shot, muzzle-loading rifles. Yet this small band would outfight and outfox an enemy force that eventually grew to 1,000 troops. Ultimately, the army would force the Indians to surrender, but not before guerrilla tactics and a harsh, unfamiliar landscape had humbled many seasoned veterans of the Civil War.

Before the Lost River fiasco, few Americans knew of the Modoc, a small tribe of about 600 Indians who had lived until 1864 on a 5,000-square-mile tract along the California-Oregon border. Although they fought encroaching miners and settlers, they eventually accepted the newcomers and adapted. The men cut their hair short, wore Western clothes, and took the names white men gave them.

In 1864 the Modoc chief Kientpoos, known to whites as Captain Jack, signed a treaty and reluctantly moved his people to the Klamath Reservation in southern Oregon, which they had to share with the Klamath and Yahooskin tribes, neither of whom were friends. Unhappy, Captain Jack and 183 Modocs decamped for their ancestral homeland on Lost River in 1870.

Captain Jack’s people harmed no one. Nevertheless, skittish settlers demanded their removal. The Indian superintendent for Oregon ordered the local army commander, Major John Green, to return the Modocs—forcibly if necessary—to the reservation. Without notifying his higher-ups, Green sent Jackson on his ill-fated November mission to Lost River.

On the same day Jackson and his men tangled with Captain Jack, a dozen white settlers took it upon themselves to capture the nearby camp of Hooker Jim, a Modoc sub-chief. The warriors drove off the Oregonians with a single volley, but not before a soldier’s load of buckshot killed a Modoc baby. Full of fury, Hooker Jim and his followers left Lost River to join Captain Jack, and during their two-day ride, they killed 11 settlers in retaliation for the baby’s death—slayings that would later earn Hooker Jim a death sentence from an Oregon court.

After these skirmishes, the Modoc assembled in the Lava Beds, a sagebrush-mottled region south of Tule Lake. A labyrinth of paths cut through the Lava Bed’s boulders and natural parapets. Bunch grass blanketed the rocks, making approaches to the Modoc encampment appear easy. The Indians called the sanctuary their “stone house.” The army would call it “Captain Jack’s stronghold.”

The duty of reducing the stronghold fell to the commander of the Military Department of the Columbia, Brigadier General Edward R. S. Canby. Kind and conciliatory, Canby had few grand ambitions. During his 33-year army career, he had compiled a solid if unspectacular record that included stints fighting Seminoles in Florida and Navajos in the New Mexico Territory. Indeed, he had more face-to-face experience with Indians than most generals, having negotiated the unconditional surrender of 24 Navajo chiefs.

During the Civil War, Canby enjoyed several battlefield successes, most notably a victory at the Battle of Glorieta Pass, which has been called “the Gettysburg of the West.” In late 1862, he was assigned to staff positions in the east, where he had a falling-out with Ulysses S. Grant. In his memoirs, Grant damned Canby with faint praise: “There have been in the army but very few, if any, officers who took as much interest in reading and digesting every act of Congress and every regulation for the government of the army as he….His services were valuable during the war, but principally as a bureau officer.”

Canby’s opposite in the Modoc camp, Captain Jack, fiercely desired a home off the reservation. But he was a peaceable man who hoped to reach an agreement without violence. Cho-ocks, the Modoc shaman, meanwhile, stoked the tribe’s war fever. Called Curly Headed Doctor by whites, the shaman knew that he would lose his standing in the tribe if the Modocs returned to the reservation, where officials insisted on converting the Indians to Christianity. He promised his followers that his powers would make the stronghold impenetrable.

On January 15, 1873, nearly two months after the Lost River battle, the army finally moved. Canby and Colonel Frank Wheaton, taking over from Green as field commander, had methodically assembled troops from throughout the Department of Columbia until 431 men stood ready to attack—more than seven times the Modoc force. Wheaton’s was a mixed command of 214 regulars (three troops from the 1st U.S. Cavalry and two companies from the 21st U.S. Infantry); 60 members of the Oregon militia; 24 California volunteers; 30 Klamath scouts of questionable loyalty; and 15 Snake Indians.

Wheaton composed a simple plan of battle. Captain Reuben F. Bernard was to attack the stronghold from the east with two troops of cavalry. From a ridge three miles west of the stronghold, Major Green was to advance with the main body. Wheaton intended for Green and Bernard to join forces south of the stronghold, blocking a Modoc escape deeper into the Lava Beds. All the soldiers were to fight dismounted. Fire from Coehorn mortars would provide artillery support.

Operations began on the morning of January 17. Nothing went as planned. The day dawned damp and foggy, and with the poor visibility, Wheaton withheld mortar fire for fear of hitting soldiers. Green’s command advanced blindly. Tearing their boots on the razor-sharp lava rocks, the soldiers inched forward along a three-mile front. None of the men could see anything but the muzzle flashes from Modoc rifles. Moving easily over the rocky ground they knew so well, the Modocs made a shambles of Green’s command and even taunted their enemy. When a wounded captain cried out, Modoc women laughed at him. “You come here to fight Indians and you make noise like that,” one jeered. “You no man.”

Green’s regulars covered just two miles in four hours. The Oregon volunteers dispersed early in the fight; the Klamath scouts, meanwhile, sat out the skirmish and slipped ammunition to their Modoc cousins.

Bernard fared even worse than Green. After losing five men, he huddled with his command among icy rocks. Green, with no chance of joining flanks south of the stronghold, slipped around the northern edge and withdrew with Bernard to the east. Wheaton had lost 12 dead and 26 wounded; no Modocs had been hit. “To sum up,” said one soldier, “we were eager to get in and glad to get out.”

Victory strengthened Curly Headed Doctor’s influence among the Modocs. Stunned by the army’s poor showing, the government sent a four-member peace commission to open negotiations. Talks dragged on for three months. That no peace was possible should have been obvious. The Modocs wanted their Lost River land and amnesty for Hooker Jim and his warriors in the murders of the settlers. The negotiators didn’t have authorization from Washington to grant either request. After two commissioners resigned in disgust over the interminable talks, Canby became de facto head of the group. The Grant administration gave him total control over what it called the “Modoc affair”; he could negotiate or fight as he thought best.

By mid-March, Canby had more than 500 men, evenly distributed between Colonel Alvan Gillem, who had replaced Wheaton after the debacle at the stronghold, and Major E. C. Mason, who had assumed command from Captain Bernard.

In the Modoc camp, meanwhile, a treacherous plot was afoot. Some of Captain Jack’s followers wanted to assassinate Canby at the next negotiating session, believing the U.S. soldiers would stand down if their commander was killed. Captain Jack opposed the idea but eventually agreed to lead the assassins—if Canby was given one last chance to meet the Modoc demands.

Canby learned of this scheme from one of his translators, Toby Riddle, a Modoc woman who had married a California pioneer also working as a translator. Riddle’s loyalty was beyond question, but Canby refused to believe that the Modocs would risk rash action when they were greatly outnumbered. He agreed to meet Captain Jack and five unarmed Modocs on Good Friday, April 11, at a council tent between the lines. The other commissioners and the Riddles reluctantly agreed to accompany him.

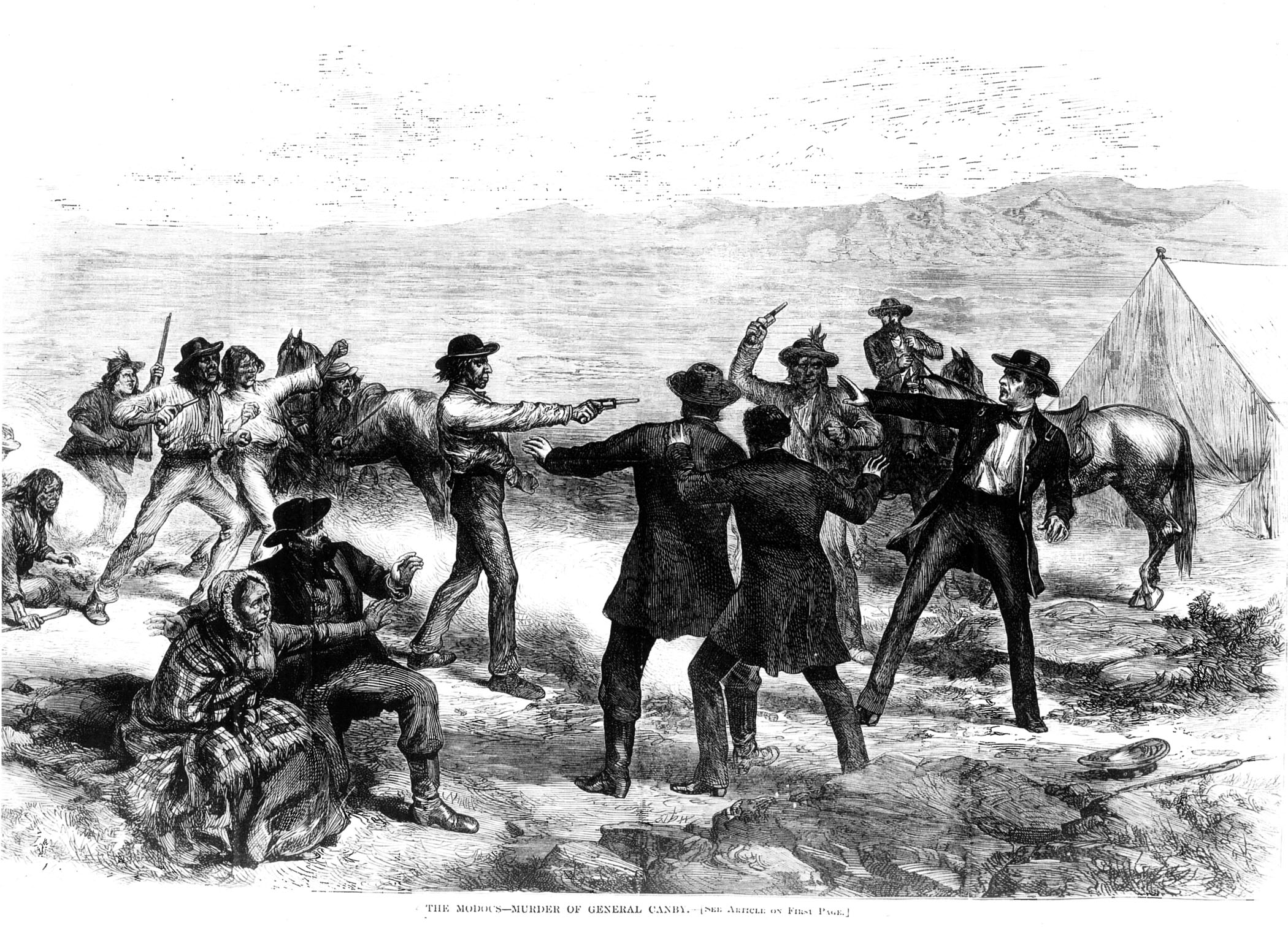

On the appointed day, Canby’s delegation arrived at the tent to find Captain Jack and seven armed warriors. The chief begged Canby to withdraw his troops; the Modocs in turn would accept the Lava Beds as a home. One commissioner later recalled that “all seemed to feel that if [Canby] assented to the withdrawal of the army the trouble would be passed over.” But Canby’s orders precluded him from abandoning the Lava Beds. The Modocs must surrender unconditionally, he told Captain Jack.

With that, the Modoc chief drew a pistol from his shirt and shot Canby in the face, killing him. The other warriors opened fire, slaying one of the commissioners, the Reverend Eleazer Thomas, and wounding another. Quick thinking by Toby Riddle prevented more bloodshed; she shouted that soldiers were coming, confusing the Modocs and helping the others escape.

The murder of General Canby shocked the nation. Commanding General of the Army William T. Sherman authorized the new Columbia department commander, Colonel Jefferson C. Davis, to use “any measure of severity against the savages.”

Davis would need two weeks to reach the Lava Beds from his headquarters in the Washington Territory. In the meantime, the fight belonged to Colonel Gillem. Four days after Canby was killed, he ordered Green and Mason to attack Captain Jack’s stronghold using the tactics Wheaton had tried earlier. Mason took up an assault position 700 yards east of the stronghold; Green, with the dismounted cavalry, advanced from the northwest.

This second attack fared only slightly better than the first. The Modocs again hid themselves in their lava-rock defenses. Captain Jack sent eight warriors out of the stronghold to harass the attackers as they advanced. Exposed to fire from a well-concealed enemy, the battle line of soldiers unraveled quickly on the broken ground. Officers herded the men forward as best they could, but Modoc snipers picked them off. Field howitzers that might have dislodged the enemy shooters were placed too far to the rear.

For six hours, the attackers picked their way through the lava rocks and rifle fire, covering only a half mile before the attack sputtered out at dark. The soldiers did kill one Modoc warrior. More important, they held their ground and built rock breastworks. The howitzers were brought forward, and mortars lobbed shells into the stronghold during the night.

Gillem renewed the attack the next morning, killing another warrior and inching into the Modocs’ defenses. With Curly Headed Doctor’s medicine apparently failing, the Modocs turned to Captain Jack. He withdrew before dawn on April 17, the second day of the army’s attack, and took his people along a hidden path deep into the southern reaches of the Lava Beds. Despite the opportunity to pursue the Indians and take the upper hand, Colonel Gillem declined to give chase. “Apathy had settled on him,” one lieutenant pronounced, “and like a nightmare seemed to follow him about.”

The Modocs delivered another humiliating blow to the army forces about a week later. On April 26 Gillem sent a 67-man patrol from the 12th U.S. Infantry to look for an artillery position two miles south of the stronghold in case the Modocs were nearby. Captain Evan Thomas, who had no Indian-fighting experience, led the patrol. He marched without protecting his flanks and called a lunch break in the shadow of a sand butte—a position extremely vulnerable to an ambush. After the troops had settled into their meal, 34 warriors under the Modoc leader Scarfaced Charley opened a blistering fire that killed or wounded half the command and sent the rest running. Among the dead was Thomas. The Modocs suffered no losses.

The officers and troops blamed Gillem for the April 26 “Thomas Massacre.” Colonel Davis arrived a week later and took charge. Determined to end the standoff with the Modocs, Sherman roughly doubled Davis’s force to nearly 1,000 men. Reporting that he had “restored a command demoralized by improper management,” Davis prepared to take the offensive.

Fortunately for Davis, his fresh troops included 70 scouts from the Warm Springs Indian tribe, enemies of the Modoc. They reported the whereabouts of Captain Jack and his band, who were now heading southeast, deeper into California. On May 9, Davis sent the Warm Springs Indians and three mounted companies to find them. That night the troops made camp alongside a large dry marsh the soldiers called Sorass Lake. The men bedded down within range of a bluff, taking little care for their safety.

The stage seemed set for another slaughter. At dawn the next day, Scarfaced Charley’s warriors opened fire from the bluff. Eight soldiers fell, and the cavalry horses stampeded. But the Warm Springs Indians kept their ponies and galloped around the Modoc flanks. A cool-headed sergeant yelled to his frightened men, “God damn it, let’s charge!” and several dozen soldiers swept up the bluff. Outflanked, the Modocs fled west.

The defeat splintered the Modocs. Hooker Jim and Curly Headed Doctor drifted west with part of the band, and Captain Jack headed east with the remainder. Out in the open, the Modocs stood little chance against the cavalry patrols. On May 22, Hooker Jim surrendered his followers to Colonel Davis. In exchange for his life, he offered to help track down Captain Jack. Davis believed Hooker Jim deserved to be hanged but agreed to his terms, reasoning that his betrayal would discourage other restless tribes from going to war.

Hooker Jim kept his word. On May 28 he helped the army corner Captain Jack in a cave 10 miles east of the Lava Beds. The six-month war was over.

In July a military commission sentenced Captain Jack and four other Modocs to death for the murders of Canby and Eleazer Thomas, the civilian peace commissioner. Grant commuted the sentence of two of the Modocs to life in prison. On October 10, 1873, Captain Jack and two accomplices were hanged. After he was lowered from the gallows, the Modoc chief was decapitated, and his head was sent to the curator of the Army Medical Museum, who made a hobby of studying Indian crania.

No one gained from the conflict. Sixty-eight soldiers died and 75 were wounded. Although the Modocs suffered just five killed and three wounded, the Interior Department ordered the surviving members of the tribe exiled to the Indian Territory, where dozens quickly succumbed to disease.

What’s now known as the Modoc War cost the government more than half a million dollars; the small parcel of Modoc ancestral land on Lost River was worth less than $10,000. Just three years later, the army would again underestimate an Indian foe, this time at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, with even more lethal consequences.

Originally published in the Summer 2011 issue of Military History Quarterly. To subscribe, click here.