“Fokker is still the old Fokker,” wrote Lieutenant Rudolf Stark after seeing Fokker D.VII and E.V fighters on August 24, 1918, “for every new machine he brings out is a considerable improvement on the last. Other firms also bring out new machines, but they are generally content with a few superficial alterations that do not effect much improvement in the flying and fighting capacities.”

Beginning in 1915, when he introduced his E.I fighter with a machine gun synchronized to fire between propeller blades, Dutch-born aircraft designer Anthony Fokker had acquired a reputation in German air service circles for innovation. But in the course of developing such elegant designs as the Dr.I triplane, D.VII biplane and E.V monoplane, he made a few wrong turns. The most glaring of those deviations was the Fünfdecker (fivewinged) Fokker V8.

The V8 was the mutant offspring among an extensive crop of triplanes, a craze touched off by the stunning maneuverability, climb rate and overall performance displayed by the British Sopwith Triplane in the spring of 1917. In response, the Inspektion der Fliegertruppen, or Idflieg—which had earlier favored sesquiplane wing designs in reaction to the success of France’s Nieuport 11 and 17 fighters in 1916—ordered virtually every German airplane builder to produce a triplane of its own. Just about all of them did, too, but ironically the most successful Dreidecker was created by the designer least enthusiastic about doing so.

Early in 1917, Anthony Fokker had been test-flying a new series of aircraft based on a box spar wing structure pioneered by Swedish-born engineer Villehad Forssman. Although Fokker knew of Hugo Junkers’ all-metal cantilever wing aircraft, he decided that Forssman’s wooden structure offered a lighter airframe for the power that engines of the time could provide. The first of Fokker’s experimental Verspannungslos (“without external bracing”) designs, the V1 and V2, were sesquiplanes with plywood-covered wings and fuselages, respectively powered by air-cooled rotary and water-cooled inline engines. Promising though they were, however, Fokker was aware of Idflieg’s triplane requirement even before it was issued in June—and with his own designs having been eclipsed by the Albatros D.I, D.II and D.III fighters in the fall of 1916, he was not about to pass up an opportunity to regain his prominence in the industry. He therefore took the fuselage of a V3, a rotary engine biplane fighter he’d been building for the Austro-Hungarian air service, and reconfigured it as a triplane, the V4.

To save weight, canvas rather than plywood covered the V4’s steel tube fuselage frame and plywood box spar wing structure. The wings originally had no interplane struts, but during development they were slightly increased in span, necessitating a set of I-shaped struts. Balanced ailerons and elevators were also added. A captured 110-hp Le Rhône engine provided power, with production aircraft using a German-built copy, the Oberursel Ur.II.

While the improved V4—later redesignated the V5—was undergoing testing late in June, Fokker also produced the V6, with a 120-hp Mercedes D.II 6-cylinder watercooled inline engine, but it proved to be heavy, slow and sluggish compared to its rotary counterpart. The rotary engine V5, however, impressed pilots and the Idflieg favorably enough for Fokker to begin work on three preproduction F.Is. Two were issued to Jagdgeschwader I on August 28, 1917, and although both were destroyed by the end of September, their achievements in the hands of renowned aces Manfred von Richthofen and Werner Voss made them the talk of the Western Front and sealed a production deal under the designation of Dr.I.

German airmen who had seen a new generation of Allied fighters such as the Spad VII, S.E.5a and Sopwith Camel outclass their structurally unreliable Albatros D.Vs and sluggish Pfalz D.IIIs looked to the new triplane, which offered stunning maneuverability and climb rate, with high hopes in the fall of 1917. They were in for a disappointment, however. A sudden rash of upper-wing failures in late October and early November revealed internal rot and structural inadequacies that led the Idflieg to halt production until Fokker took steps to fix them. Fokker did so, and Dr.I deliveries resumed in December.

Even then, though the Fokker Dr.I went on to become one of the most famous aircraft of World War I, it proved to be less than the answer to German fighter pilots’ prayers. Its rotary engines required fine castor oil for lubrication, but the Allied maritime blockade made castor beans a scarce commodity. German-developed chemical substitutes tended to burn up rapidly, especially in warm weather, resulting in entire squadrons of Dr.Is being grounded in June 1918. Above all, with a maximum speed barely topping 100 mph, the Dr.I was too slow for an air superiority fighter.

Characteristically, Fokker was already addressing the speed problem. He built four V7s, stretched to accommodate more-powerful rotaries and Siemens und Halske’s 160-hp rotary-radial engine, but testing did not yield sufficiently improved performance to justify further development. Fokker then turned back to the V6, with its more reliable water-cooled engine. More power could give it greater speed, but would it retain the agility to which triplane pilots were becoming accustomed? Enter the V8.

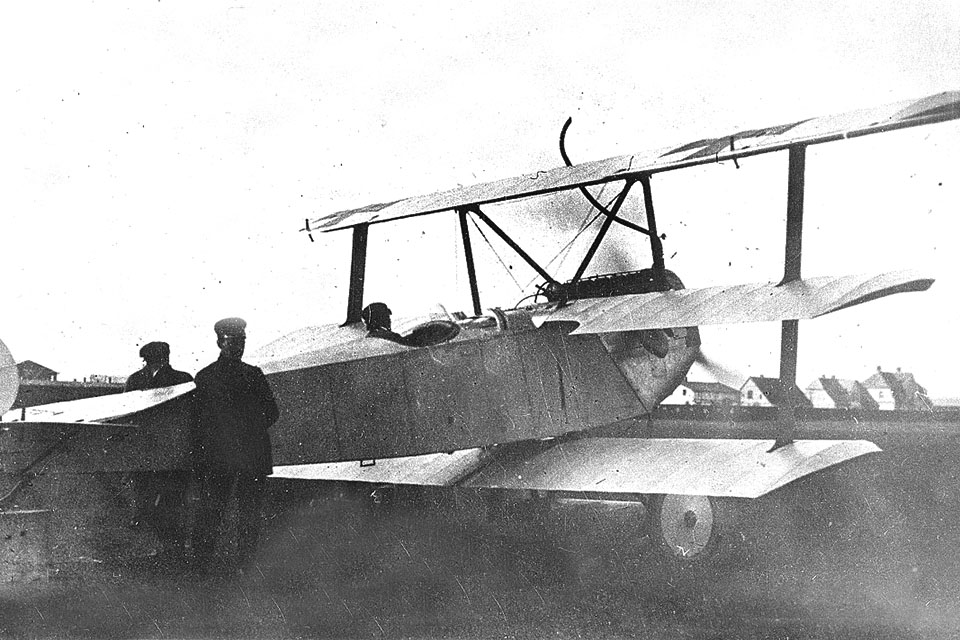

Uniquely radical among Fokker’s Verspannungslos menagerie, the V8 had its main three wings moved up to the cowling just aft of the propeller, seemingly suspended on the upper and lower sets of cabane struts that sprouted from the tubular steel mounting for its Mercedes engine. The aft center section of the lower wing had to be partially cut away to make room for the wheels. Two more wings were similarly strut-mounted above and below the fuselage aft of the cockpit. Balanced ailerons were installed on both upper wings, fore and aft. In contrast to other Fokkers of the time, there was no stagger to either wing set. Tail surfaces consisted of the same triangular-shaped horizontal stabilizer, balanced elevators and comma-shaped rudder that were standard on the Dr.I.

For want of any other takers, Fokker himself took his freakish creation up for two brief test hops about a week apart during October 1917. None too surprisingly, he concluded that five wings were not better than three, scrapped the V8 and resumed his experiments with biplanes, starting with the rotary engine V9 and the inline V11. The latter, with its interplane and cabane strut arrangements, became the prototype for the plane that Fokker and the German fighter pilots had been awaiting for so long. It dominated the German fighter competition of January 1918 and, after further modifications, achieved production, combat success and universal fame as the deadly Fokker D.VII.

Originally published in the July 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.