Germany’s Fokker D.VII embodied all the characteristics considered most important for a successful fighter aircraft during World War I, and many aviation historians regard it as the finest all-around fighter of its day. Its appearance in the spring of 1918, coinciding with the last great German offensive of the war, represented the final and most formidable challenge to Allied aerial supremacy over the Western Front.

There is no question that German aviators regarded the D.VII as far superior to the Albatros, Pfalz and Fokker triplane fighters it replaced. So impressive was its reputation, in fact, that when the war finally ended in November 1918, the D.VII enjoyed the dubious distinction of being the only aircraft type specifically mentioned in the armistice agreement (a fact that the plane’s producer, Anthony Fokker, never ceased to remind his prospective customers of in future years).

The German air service might never have had the D.VII were it not for the persistence of a foreign airplane builder. A Dutchman born in the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia), Anthony Fokker was a far cry from the popular image of the stodgy, meticulous, science-minded German engineer. Fokker, an inattentive student who preferred sports and tinkering with mechanical devices to schoolroom studies, had a natural flair for both flying and business, and he became a flamboyant entrepreneur. Although he was always an outsider among the German high command, Fokker’s flying expertise enabled him to achieve a rapport with many of Germany’s frontline combat aviators, and he wasn’t above using those relationships to his advantage in securing military contracts. When it came to engineering, his aircraft designs were created more by a process of empirical trial and error than through scientific or technical knowledge. But Fokker was shrewd enough to recognize the value of other engineers’ good ideas when he saw them, and knew how to capitalize on them.

After Anthony dropped out of high school, his father sent him to Germany to study mechanics. Bitten by the aviation bug in 1908, he dropped out again and constructed his own airplane in 1910. By the time WWI began Fokker had established his own aircraft manufacturing company in Germany, where he produced a series modeled after the highly successful French Morane-Saulnier monoplanes. Fokker’s products, which featured stronger wooden wings and an innovative lightweight steel-tube framework for the fuselage and tail surfaces, were actually considered superior to the Morane-Saulnier originals.

As a non-German, Fokker lacked access to the best German aero engines of the day. Instead he had to make do with license-built copies of the French Le Rhône rotary power plant, manufactured by the Oberursel factory, which Fokker owned. While lighter than the water-cooled German engines, the rotaries were less powerful and not as reliable. They also had the disadvantage of requiring lubrication with castor oil, which was in short supply in wartime Germany.

Fokker applied for German citizenship in December 1914 (he would later claim that he was coerced into it so that his company could continue to get orders from the German military). But his firm was still denied access to the more advanced aero engines, and his rotary-engine products were regarded as second-rate. That situation changed in the summer of 1915, when Fokker developed the first successful system for synchronizing a machine gun to fire through the whirling blades of an airplane’s propeller. By installing a machine gun fitted with his new interrupter gear into his M-5 monoplane in May 1915, he produced the first truly effective fighter in history, the Fokker E.I. Although his plane’s airframe may have been based on the Morane-Saulnier, with a less-than-ideal rotary engine, the German air service couldn’t ignore the fact that Fokker’s new machine outclassed everything else in the air at that time. Introduced into combat in July 1915, the “Fokker Scourge” dominated the skies over the Western Front for the next year, and Allied airplanes and their hapless crews became known as “Fokker Fodder.”

By the summer of 1916, however, the Fokker Eindeckers were fast becoming obsolete. Fitted with only one machine gun and using the same rotary engines, Fokker’s D.II and D.III biplane fighters were being outclassed by efficient new Mercedes-powered Halberstadt fighters and even deadlier twin-gun Albatros D.I and D.II biplanes. In fact, the Fokker D.III was then seen as so mediocre that the Germans offered to sell some to the neutral Netherlands. Fokker’s Mercedes-powered D.I and D.IV biplane fighters were also outperformed by their contemporaries, and suffered from so many structural and quality-control problems that they were relegated to training duties.

Technology had moved on, and Fokker had been left behind. His aircraft were held in such low regard that the Inspektion der Fliegertruppen, or Idflieg, actually ordered him to undertake license manufacture of another company’s design, the AEG C.IV.

During mid-1916, when Fokker’s aircraft manufacturing career was at its lowest point, several events occurred to reverse his fortunes. In June his chief designer, Martin Kreuzer, died in a plane crash. He was replaced by Franz Möser, who would subsequently be responsible for designing the highly successful Dr.I triplane, D.VII biplane and D.VIII monoplane fighters. During that same period, the German air ministry encouraged the merger of Fokker’s company with that of Hugo Junkers, in an effort to utilize Fokker’s facilities for the production of Junkers’ revolutionary new all-metal monoplanes. Fokker never actually built any Junkers planes. Much to Junkers’ annoyance, however, he did adapt Junkers’ design for a thick-section cantilever wing to wooden construction, by means of a box-spar structure pioneered by Swedishborn engineer Villehad Forssman, and applied it to his own succeeding airplane designs.

At Fokker’s direction, Möser initiated the development of a series of prototypes utilizing the new wooden cantilever wing. So radically different were these new airplanes that, in place of the “M” numbers assigned to previous Fokker prototypes, they were designated with numbers prefaced by “V” for Verspannungslos, or cantilever. The first of them, the V-1, flown in December 1916, was a sesquiplane with no external bracing wires. Neither it nor the succeeding V-2 was considered suitable for operational service, but when Idflieg, perhaps overly impressed with Britain’s Sopwith Triplane, ordered all German manufacturers to produce triplanes of their own, Fokker adapted the new wing to his offering. The V-3 triplane prototype, introduced in the summer of 1917 and further refined as the V-4, was ordered into pre-production as the F.I. After a short but spectacular career in the hands of Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen and Werner Voss, the type was approved for mass production as the Dr.I (for Dreidecker, or “tri-wing”).

Fokker’s first successful fighter since the E.III monoplane of early 1916, the Dr.I seemed likely to redress the balance of air power over the Western Front as effectively as Fokker’s monoplanes had two years earlier. The new triplane had barely arrived at frontline squadrons in late October, however, when quality-control issues arose with it, costing the lives of several pilots. All Dr.Is were grounded until modifications could be made, and Idflieg came close to canceling its order for the new fighters. Fokker always insisted that the quality issues were largely the result of the poor raw materials made available to his company by the German government. Whatever the root cause, the damage was done. Only 320 Dr.Is were ever built.

The Dr.I featured excellent climb capability and maneuverability, but it was still powered by the same 110-hp Oberursel rotary engine that had propelled the E.III. That factor, along with the aerodynamic drag generated by the three wings, kept the Dr.I’s level speed markedly slower than those of the new S.E.5as and Spad XIIIs then being introduced by the Allies.

Concerned about the Dr.I’s shortcomings as well as those of its stablemates, the structurally weak Albatros D.V and the sluggish Pfalz D.III, Idflieg arranged a competition for a new fighter to replace them all, to be held in January 1918. One of the stipulations was that all entrants would be powered by the 160-hp Mercedes D.III liquid-cooled, 6-cylinder inline engine. Anthony Fokker was thus finally allowed access to the more sophisticated and higher-powered aero engines that had been largely denied him up to that time.

The competition included no fewer than 31 different planes from 10 different manufacturers, eight of which were submitted by Fokker. All the planes were to be evaluated both by test pilots and by experienced combat aviators. Fokker’s main hopes were pinned on his V-11, a biplane design that was based upon the fuselage of the Dr.I, fitted with the Mercedes D.III engine and a set of wooden cantilever wings. The “Red Baron” Richthofen, Germany’s leading ace, flew the V-11 and liked it a great deal, though he told Fokker he thought its coffin-shaped fuselage was a bit too short, rendering it directionally unstable under certain circumstances. Fokker added several inches to the rear fuselage, as well as a small triangular fin, and the V-11 became the unquestioned winner of the competition.

After further refinement, the new fighter was ordered into production as the Fokker D.VII. Much to Fokker’s satisfaction, Idflieg ordered his archrival, Albatros, and its subsidiary, the Ostdeutsche Albatros Werke (OAW), to manufacture the D.VII under license as well—paying Fokker a royalty for each one they built.

In an interesting example of the way Anthony Fokker operated, he did not prepare any production drawings of the D.VII. Instead he simply sent a complete airplane to Albatros to dismantle and analyze—from which it produced its own production drawings. As a result, parts from Albatros-built D.VIIs were not interchangeable with those of Fokker-built aircraft. Ironically, but perhaps not too surprisingly, the Albatros- and OAW-built copies were considered better made than the Fokker originals.

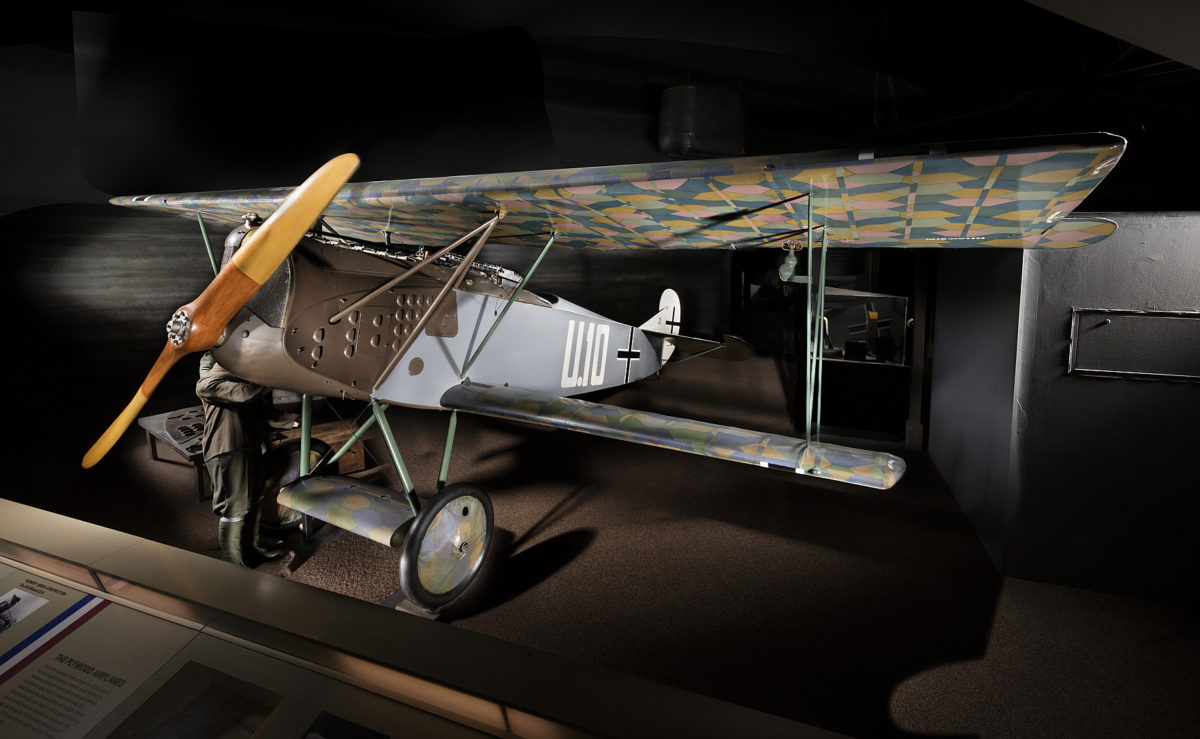

Unlike most wooden-framed aircraft of the era, the Fokker D.VII’s fabric-covered fuselage and tail surfaces were built on a strong but lightweight framework of welded steel tubes. All the external wing and landing gear struts were also fabricated from streamlined steel tubes. The wings, however, consisted of a plywood box structure with the leading edges clad in plywood veneer and the remainder covered with fabric. The lift, compression and torsion loads were handled by thick box spars within the airfoil section rather than by drag-producing external bracing wires. In addition, the D.VII’s wings required no adjustments by ground crew riggers, as did most other aircraft in those days. The design was essentially a wooden adaptation of Junkers’ all-metal cantilever wing, which was too heavy to achieve widespread use until more powerful engines became available.

Like the Dr.I, the D.VII included another unique Fokker feature: an airfoil built onto the axle between the landing wheels. That airfoil allegedly provided enough aerodynamic lift to support the weight of the landing gear in flight.

Fokker D.VIIs began arriving at frontline squadrons in April 1918, just in time to participate in Germany’s last spring offensive of the war. The Red Baron, who had championed the new fighter at the January competition, was among the pilots eagerly awaiting its arrival, but he never had the opportunity to find out what he could do with it. The victor of 80 aerial combats and indisputably the most successful fighter pilot of World War I, Richthofen was killed on April 21 while flying his by-then-obsolete Dr.I triplane.

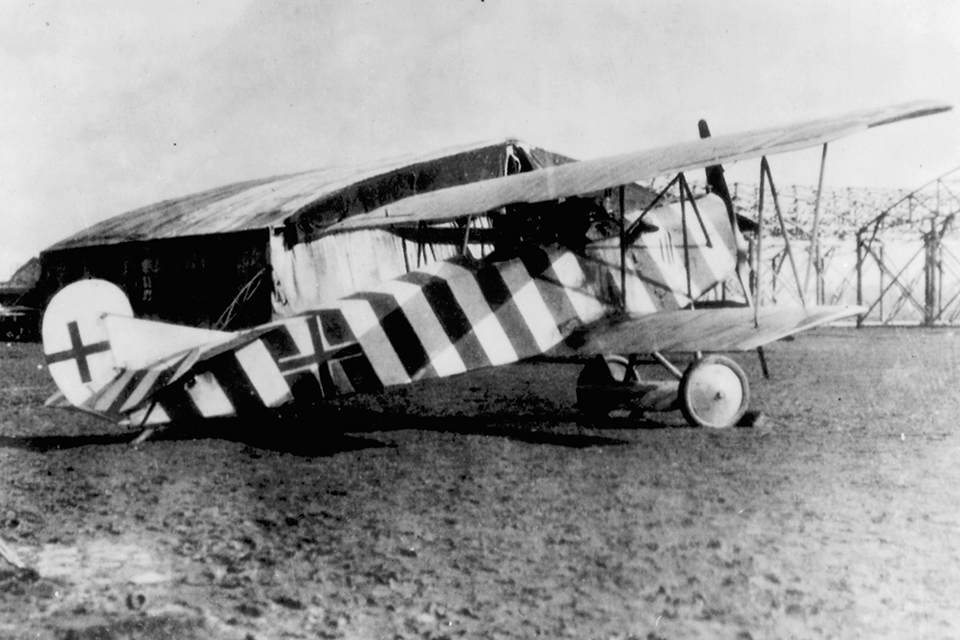

The D.VII’s introduction to combat provided both a qualitative and morale boost to the German air service, and a shock to its Allied counterparts. Although its coffinlike fuselage looked less streamlined than those of its elegant-looking Albatros and Pfalz predecessors, the boxy Fokker performed better because it was lighter, stronger and possessed more efficient wings, which gave it superior lift characteristics compared to its thin-winged contemporaries. In fact, the D.VII’s thick-sectioned wings were so efficient that at low speeds the fighter could virtually hang on its prop, a trick often witnessed by Allied pilots during dogfights.

Not only did the Fokker’s wing design endow it with a superior rate of climb and maneuverability, it also enabled the fighter to maintain those advantages at higher altitudes than its chief Allied opponents, the Spad XIII and S.E.5a. Although the supremely nimble Sopwith Camel could still outmaneuver the Fokker at lower altitudes, the power of its rotary engines began to fall off above 12,000 feet, while the D.VII could still function effectively at 20,000. Furthermore, the D.VII’s strong cantilever wing structure bestowed a higher diving speed than was possible in the preceding Albatros D.V and D.Va sesquiplanes, whose wings had a tendency to break when overstressed.

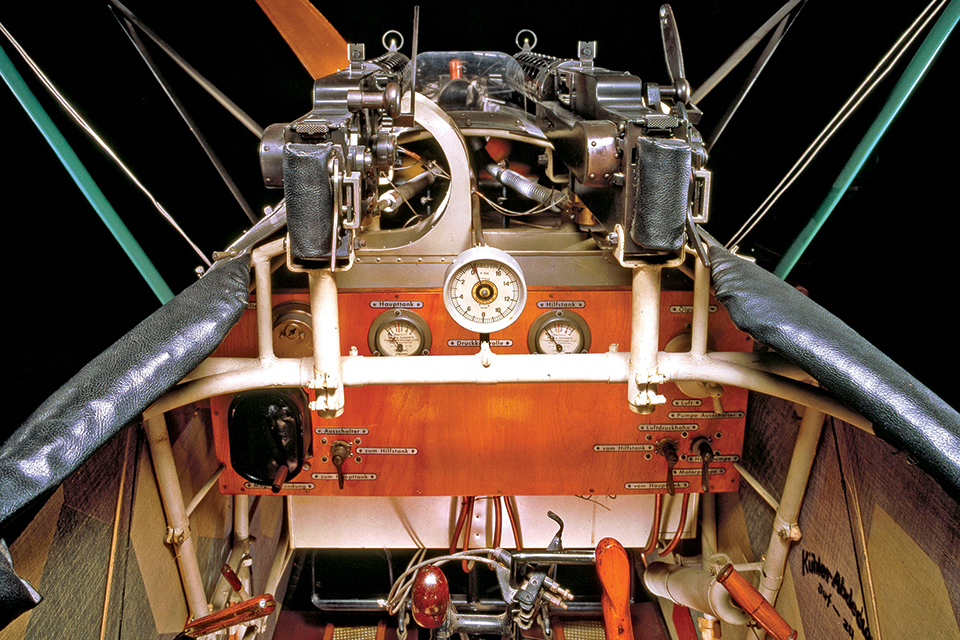

While early D.VIIs were powered by the 160-hp Mercedes IIIa, that engine was eventually superseded on the production line by an improved higher-compression 180-hp version, the IIIaü, and the 200-hp IIIaüv. Better yet, during the summer of 1918 the new D.VIIF appeared, powered by a 185-hp BMW IIIa engine. It became the most coveted version of the fighter among knowledgeable German aces. The BMW engine raised the maximum speed from 116 to 124 mph, and climb to 2,000 meters was reduced from eight minutes to six. Just as important, the engine maintained its power output at higher altitudes better than the Mercedes.

The Fokker D.VII was 23 feet long and had a wingspan of 29 feet 3½ inches. In an effort to improve the pilot’s downward visibility, the lower wing was somewhat smaller than the upper. Wing area was 219 square feet, and armament was two synchronized 7.92mm Maxim 08/15 machine guns with 500 rounds per gun. Gross weights varied with the engine used; the 160-hp Mercedes version weighed 1,936 pounds, while the 185-hp BMW version weighed 1,993 pounds.

Besides possessing the best fighter, German pilots enjoyed other advantages over their Allied counterparts in 1918. For one thing, they began to be issued parachutes, which while not as reliable as modern chutes, at least gave them a fighting chance of escaping alive in an emergency. Another innovation introduced on the D.VII was a rudimentary high-altitude breathing system. It may only have been a compressed air tank with a valve and a tube, terminating in a mouthpiece like the stem of a tobacco pipe, but it was better than struggling for breath at 20,000 feet, as Allied pilots did.

About the only significant design flaw the D.VII exhibited pertained to its armament. The two machine guns were well placed and accessible to pilots, but the ammunition supply, forward of the cockpit, proved to be too close to the engine bay. There were instances of ammunition “cooking off” in D.VIIs while airborne, setting the planes on fire. Several pilots lost their lives as a result, including 21-victory ace Fritz Friedrichs, killed when his D.VII caught fire on July 15, 1918. The problem was eventually alleviated with better ammunition and by cutting additional cooling louvers in the metal cowling.

By the end of the war some 70 German fighter squadrons had been equipped, either wholly or in part, with D.VIIs. German pilots regarded it as by far their best fighter, and widely believed that it could transform a mediocre pilot into a good one, and a good one into an outstanding one. There never seemed to be enough D.VIIs to go around. Units that were issued improved versions of older designs, such as the Albatros D.Va or Pfalz D.IIIa, or supplementary new types such as the Roland D.VI or Pfalz D.XII, were apt to think they’d had to settle for an inferior second best, even if that wasn’t true.

Approximately 3,300 D.VIIs were manufactured by Fokker, Albatros and OAW. In spite of their qualitative superiority, however, there weren’t a sufficient number of them to stave off Germany’s inevitable defeat. Although Fokker considered the specific mention of the surrender of all D.VII fighters in the terms of the armistice extremely flattering, and it made great advertising, the seizure of all his assets at war’s end left him in a difficult position.

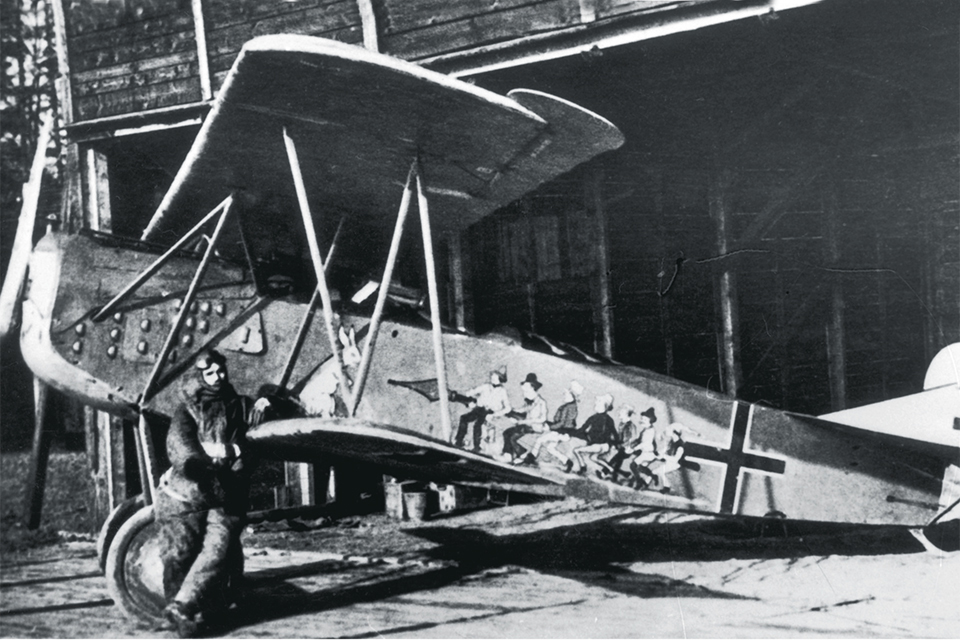

Fokker wanted to continue building civil aircraft after the war, but that was clearly impossible in Germany. Ever the slick entrepreneur, he managed to hide from the Allies 220 aircraft, mostly D.VIIs, along with 400 engines and manufacturing equipment. Social unrest was so rampant in postwar Germany that he also secretly modified a D.VII into a two-seater, with an extra fuel tank in the airfoil fairing between the wheels, in case he and his wife needed to make a quick getaway. In the end the two-seater D.VII was unnecessary. By means of bribery and other subterfuges Fokker smuggled six trainloads of planes, engines, spare parts and machinery into the Netherlands, along with himself and his wife.

Fokker landed on his feet. Largely through the sale of his smuggled planes, particularly the D.VIIs, he soon established himself as an aircraft manufacturer and celebrity in his native Netherlands. Some of the D.VIIs were sold to the Dutch air service and others were sold abroad, often clandestinely, to various foreign powers. At least 50 are known to have been exported to the Soviet Union. By the early 1920s Fokker was back in business, operating highly successful aircraft manufacturing enterprises in the Netherlands and the United States. Although he died in 1939, his aircraft company continued to operate in the Netherlands until 1996.

Frequent contributor Robert Guttman recommends for further reading: Fokker: A Transatlantic Biography, by Marc Dierikx; Fokkers of World War I, by Peter M. Bowers; and The Fokker D.VII, by Profile Publications.

Click here to build your own replica of, Herman Göring’s gleaming white Fokker DVII.

Originally published in the May 2012 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.