The E.G. Budd Company dubbed its stainless steel cargo plane the Conestoga, but “Pullman” might have been more apt.

During World War II, the United States became the “Arsenal of Democracy,” supplying vast numbers of vehicles, ships, aircraft and weapons to the U.S. armed forces and Allied nations. Not surprisingly, shortages of certain strategic raw materials were anticipated. Of particular concern was the supply of aluminum and light alloys needed for aircraft production. As a result, specific requests were issued to design aircraft manufactured from non-strategic materials that could be produced by companies outside the normal aircraft industry. Such sources were seen as particularly desirable for aircraft designated for second-line or non-combat uses, including training and transport. Of the many such airplanes developed, most were constructed using wood. But one manufacturer took the definition of “non-strategic materials” in a whole new direction.

Philadelphia’s E.G. Budd Company was not really part of the aviation industry. Founded in 1912, it had pioneered the fabrication of pressed-steel bodies for automobiles, and later manufactured stainless steel railroad passenger cars. In the early 1930s, however, Budd mechanical engineer Earl Ragsdale had come up with a new process for fabricating structures from stainless steel. Known as “shot welding,” it allowed sheets of stainless steel to be welded together without distortion, and without any loss of their tensile strength or rust-resisting properties. The welded sheets also demonstrated twice the strength of riveted structures. In 1934 Budd won acclaim when it used its shot-welding technique to build the stainless steel cars for the nation’s first “streamliner” passenger train, the revolutionary Burlington Zephyr.

Budd had also been branching out into aircraft manufacturing. In 1931 the firm built an amphibious biplane, modified from the Italian Savoia-Marchetti S.56 flying boat but fabricated using shot-welded stainless steel. Known as the BB-1 Pioneer, the aircraft failed to garner any sales or production orders, though it flew for about 1,000 hours in the U.S. and Europe before being donated to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, where it remains on display today.

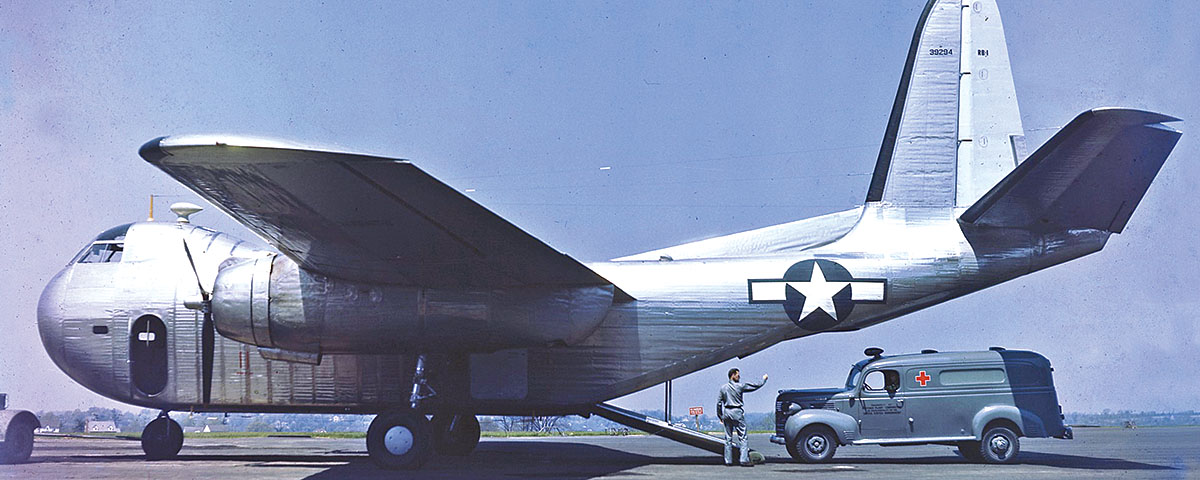

The Pioneer was the only airplane Budd produced until 1942, when it contracted with the Navy to develop a cargo plane manufactured entirely out of shot-welded stainless steel. Dubbed the Conestoga by the builder, Budd’s design resulted in a 200-plane order from the Navy under the designation RB-1. The Army Air Forces also became interested, ordering 600 aircraft under its own designation, C-93.

Flown for the first time on Halloween 1943, the RB-1 was a twin-engine, high-wing monoplane. The only exceptions to its stainless steel construction were the fabric-covered trailing edges of the outer wing panels. The Conestoga had a wingspan of 100 feet, and was 68 feet long and 38 feet 9 inches high. The aircraft featured semi-retractable tricycle landing gear, with the retracted nosewheel protruding slightly beneath the forward fuselage. Power was provided by a pair of 1,200-hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp air-cooled radials. The Conestoga weighed 20,157 pounds empty and could take off at 33,861 pounds fully loaded. In place of cargo, it could accommodate 24 fully equipped paratroops or evacuate 24 stretcher cases.

Although the Conestoga was considered odd-looking in its day, it included a number of advanced design features. The flight deck of the three-man cockpit was raised above the fuselage, leaving an unobstructed 25-foot-long cargo area. The upswept tail with a retractable ramp, another revolutionary feature at the time, facilitated cargo loading and allowed vehicles to be driven directly on or off the plane. In fact, the basic layout of the Conestoga’s fuselage was not unlike some cargo aircraft developed years later, including Fairchild’s C-123 Provider and Lockheed’s C-130 Hercules.

The Conestoga’s structural strength earned it high marks, but pilots claimed its handling was reminiscent of the railroad cars its makers were more accustomed to producing. Though powered by the same engines used in Douglas’ C-47, the RB-1 weighed 3,000 pounds more empty, making it relatively underpowered and less fuel efficient. And the Conestoga turned out to be more expensive to produce than the C-47.

Another complaint was the deafening noise level inside the RB-1’s voluminous stainless steel fuselage, which acted like an echo chamber. One former crewmember described it as like being inside a bass drum.

A sufficient supply of aircraft aluminum turned out to be the final nail in the Conestoga’s coffin. C-47s continued to pour off the assembly lines by the thousands. As a result, the Army canceled its C-93 order and the Navy reduced its RB-1 order to 25 airplanes, of which only 17 were delivered.

Although the Conestoga was the Budd Company’s last foray into aircraft manufacturing, the firm produced railway coaches until 1978, when it was taken over by the German Thyssen Allgemeine Gesellschaft. During the 1980s the company was reorganized, closing down its Philadelphia facility and phasing out railroad car production, but it remained in business in Troy, Mich., manufacturing auto body components.

Most of the 17 Conestogas built went straight from the manufacturer to storage. Soon after the war ended, the War Assets Administration offered them for sale as surplus. Fourteen were purchased by the National Skyway Freight Corporation, later known as the Flying Tiger Line, for use as commercial air freighters until the early 1950s. A few found their way to South America, continuing to serve as freighters. A single surviving example of the Budd Conestoga can be seen today at the Pima Air Museum in Tucson, Ariz., where it is currently awaiting restoration.

This article orginally appeared in the July 2016 issue of Aviation History Magazine. Subscribe here!