During the golden age of Alaska bush flying, pioneering airmen did things their way, regardless of what others thought impossible.

Legends are sparked by unbelievable deeds. So it was for Alaskan bush pilot Bob Reeve when he asked a group of mountaineers to push his airplane into position so he could take off from a cliff. In 1937 Reeve had landed famed mountain climber Henry Bradford Washburn and his team on the slopes of 17,146-foot Mount Lucania near the Canadian border with Alaska. Reeve quickly discovered the air was too thin and snow too slushy for his ski-equipped Fairchild 51 to take off. He tried three times. Then he had a crazy idea. Reeve figured if he launched off the cliff the rush of air as he plunged downward would provide the lift he needed.

Washburn vehemently protested, saying it was sure death. “I’m a pilot,” Reeve replied. “You skin your skunk and I’ll skin mine.”

Washburn’s party then pushed the Fairchild into position for Reeve to make a takeoff run off the cliff and were shocked when he actually did just that. The bush pilot went over the cliff and out of view. That was the last Washburn saw of Reeve until a press conference months later when the pilot walked in. Stunned, Washburn stood up, pointed at Reeve and declared he was “the greatest pilot who ever lived!”

Reeve was one of only 50 pilots who flew in the Territory of Alaska before World War II. The period from 1924, when Carl Ben Eielson first took off into the Alaska sky, to the war is considered the golden age of the Alaska bush pilot. For these men there were very few government regulations on flying, and what little enforcement the Civil Aeronautics Authority undertook in the late 1930s was conducted by a handful of agents sprinkled across what amounted to a subcontinent. Thus, planes flew overloaded, sometimes with drunken pilots at the controls. Damaged and worn out aircraft were mended with wire, tape and, in one case, tree branches.

Flying to the point of addiction, these bush pilots faced adverse weather and deep subzero cold in frail aircraft powered by undependable engines. They landed where there were no runways on a daily basis. Reeve joked he was not flying an airplane at all but a collection of assorted parts that happened to be flying in formation.

Almost one-fifth the size of the United States or two and a half times bigger than Texas, Alaska’s terrain encompasses glaciers the size of small states, the highest mountains in North America, hundreds of active volcanoes and miles of endless wetlands, tundra and unmapped forests. Even today, the vast majority of Alaskan communities are inaccessible by road. For the people who populate them and the businesses they work, everything has to be either flown in or brought in by barge.

Alaska bush pilots carried groceries, mail, provided emergency medical flights and even ferried Santa Claus with presents for children to remote villages and cabins. They also flew felons handcuffed to a seat, corpses strapped to the wing and drugged polar bears. They would tie timber, pipe and even a bedspring to the outside of the plane as Sig Wien did—whatever it took to turn a profit.

Getting enough fuel in the Alaska frontier was a never-ending challenge. Gasoline and other combustibles came in 55-gallon drums. There were no automatic fuel pumps, so it had to be hand-cranked out of the drums and into the aircraft’s fuel tanks. If the cap was not put tightly back on the drum, water could get into the fuel, not to mention dirt and mosquitoes. When Joe Cross crashed in Kotzebue, a ball of mosquitoes was found to have clogged his fuel line.

They flew during the age of open-cockpit aircraft with little instrumentation and no de-icing equipment. And they crashed—over and over again. The four Wien brothers were responsible for mapping a large section of interior Alaska simply by walking out from their crash sites and noting the terrain they crossed. Accurate maps were rare. Some sections of Alaska were still using 19th-century Russian colonial charts as recently as the turn of the 21st century.

Proper flight bearings were a constant challenge for pilots. During the Alaska winter, the sun rises in the south, not the east. Compass readings are not accurate. The disparity between true north and magnetic north in Fairbanks is 27 degrees.

Like Reeve’s escape from Mount Lucania, the exploits of his fellow bush pilots became legend on some level—local, regional or national. Several, including Fairbanks’ Eielson and Anchorage’s Russ Merrill, never lived long enough to enjoy or even know of their reputations.

Tony Schwamm was landing with floats in southeast Alaska when suddenly he felt his plane being lifted upward. He had alighted on the back of a whale! Archie Ferguson was transporting a polar bear cub when it broke free of its bonds, snarling and swatting the back of his head. Soon the airwaves were filled with Ferguson screaming that the bear was loose inside his plane and was going to eat him alive. After battling the cub for 20 minutes, he reportedly made a perfect landing at Kotzebue.

The poster child of this era was Harold Gillam. Dashing, ruggedly handsome and full of personality, Gillam went where others did not dare to go. He came to Cordova in 1931 as a pilot flying in supplies and equipment to outlying mines nestled in narrow mountain valleys. In this land of sawtooth peaks and dense fog, Gilliam relied on his instruments and mathematics for navigation. He believed a good pilot could compute speed, distance and elevations of the surrounding mountains and fly in any type of weather.

Trapper “Honest John” McCreary gave Gillam the opportunity to prove his theory. During a howling snowstorm, McCreary fell and impaled himself on a large nail. His survival depended on getting to a doctor at the Kennecott mine 125 miles inland through the Chugach Mountains. Gillam loaded McCreary into his plane and took off in the blinding snow. He timed his ascent, climbing to avoid the peaks he knew were there but were hidden by the storm. Despite the unseen dangers and buffeting from high winds, Gillam delivered McCreary to the mine’s doctor. When the doctor said the man would not last the night, Gillam flew back through the storm to Cordova and brought his son back to be at his side. In that driving snow with high winds, Gillam had mastered the peaks at night for a total of 375 miles flying blind. And despite the doctor’s prediction, McCreary recovered.

This hair-raising version of early IFR flying made Gillam a hero throughout the territory. When elementary students at the Cordova school were told to compose a poem about their favorite person, a 3rd-grader wrote:

He thrill ’em / Chill ’em / Spill ’em / But no kill ’em / Gillam

“No Kill ’Em” Gillam became his nickname.

Gillam continued his mastery of early instrument flying. On another occasion Oscar Winchell was one of several pilots weathered in at McGrath. They were talking in a cabin trying to stay warm when, Winchell later said, they heard a plane land outside. In walked Gillam.

Saying hello, he helped himself to a cup of coffee while his plane was refueled. Then he collected the mail sack, stepped back into the snowstorm and took off. The pilots were weathered in at McGrath for three days while Gillam continued to deliver mail and supplies to the town and returned to Fairbanks.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Pilots began talking about three types of weather: Pan American weather, which meant the skies were clear; flying weather, the usual bad Alaskan weather; and Gillam weather, conditions in which only Gillam would fly—dense fog, violent winds and horizontal precipitation.

Not that Bob Reeve was any less daring. He had arrived in Valdez in 1932 with $2 in his pocket after being thrown off a passing freighter. There he found a wrecked Eaglerock A-7 biplane, repaired it and then leased it from the owner for $10 an hour.

The Valdez region had a number of potential gold mining sites. The problem had always been how to get equipment up to them. Sometimes Reeve would wrap old mattresses around generators, small engines and mining equipment and drop them from the air without landing. Other times he would do a “controlled crash” on an ice field, running his plane into a snowbank so it would stop. Soon he found himself with supply contracts for 13 mines in the area, earning the nickname Glacier Pilot.

Reeve upgraded to a Fairchild, charging 35 cents a pound for deliveries. His new plane was so battered, however, that he patched its floor with grocery boxes, the labels still on them. Mudflats served as his runway in Valdez. A sign hung over the shack in which he slept, advertising: “Always use Reeve Airways. Slow, unreliable, unfair and crooked. Scared and unlicensed and nuts. Reeve Airways—the best.”

Rex Beach, a friend of Wyatt Earp’s and author of the bestselling 1906 book The Spoilers, wrote magazine articles about Reeve. Women began writing to the daredevil pilot wanting to marry him. One, Janice Morisette, came up looking for him in June 1935. Reeve hid out in the Yukon Territory for a month before sneaking back to get a peek at her. She soon became Mrs. Reeve.

Eventually Reeve found the Alaska hinterland too tame and launched Reeve Aleutian Airways in 1946, taking passengers and cargo out along the storm-plagued Aleutian Islands. He died in 1980 from natural causes, but his airline continued for another two decades.

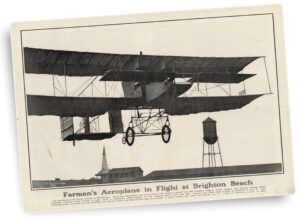

Before Alaska’s first commercial flight by Carl Ben Eielson, freight had to be hauled by dogsled to every remote corner of the vast territory. Tall and laconic, Eielson came to Fairbanks in 1922 to teach school after serving in the U.S. Army Air Service during World War I. It didn’t take him long to start thinking of making money flying supplies to the mines around Fairbanks. But to get off the ground he needed reliable income. For two years Eielson hounded the U.S. Postal Service to award him a mail delivery contract, and he was finally rewarded with the Fairbanks to McGrath route, a distance of 250 miles. The USPS shipped Eielson a Liberty-engine de Havilland DH-4B in pieces for his use and agreed to pay him $2 a mile—less than half the cost of mail delivery by dogsled.

When Eielson took off for McGrath in the open-cockpit biplane at 8:50 a.m. on February 21, 1924, the temperature was 5 below zero. As he approached McGrath a few hours later, musher Fred Milligan and his dogs were arriving at McGrath with supplies, and Eielson flew right over him. “The pilot leaned out and waved at me with his long, black bearskin mittens,” Milligan said. It was a pivotal moment for the musher as he thought it marked an end to freight hauling by dogsled. He quit dog freighting and went into the airline business, working for Pan American.

After delivering the mail and picking up his cargo, Eielson made a critical mistake—he shut down the engine to enjoy a meal. Afterward, it took him three hours to restart the de Havilland. Lesson learned. It was that way for several years as he mastered techniques to successfully fly in Alaska. All the issues to which bush pilots would need answers—such as icing or dealing with magnetic north—Eielson encountered first and found solutions. Several legendary bush pilots, including Joe Crosson, got their starts working for him.

In early November 1929, Eielson flew to Russian waters to assist a cargo vessel that had become trapped in the ice. On his second flight in, on November 9, Eielson and mechanic Earl Borland went missing. Search parties were organized and nearly every bush pilot in Alaska flew for Siberia to bring Eielson home. Crosson, who had earned a reputation for flying medical supplies to indigenous villages in the Arctic, led the effort. On January 25, 1930, Gillam spotted Eielson’s wreckage. A Soviet search party found his and Borland’s bodies under several feet of snow on February 18.

Despite the concerted effort to locate Eielson, it was not an indication that bush pilots were a close fraternity. They saw each other as competition for the same dollar. Archie Ferguson moved landing strip flags so that passengers onboard Sig Wien’s plane would have a rough landing. To steal Jack Jefford’s passengers, Ferguson would land ahead, telling waiting customers that Jefford had crashed. Yet all of them, including Ferguson, dropped everything when a pilot went missing.

Gillam continued to study meteorology and navigational aids to improve his skills. He was one of the first in Alaska to install a directional gyro, altimeter and direction-finder in his plane. But the aviation cliché that there are old pilots and bold pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots, eventually caught up with him.

World War II found Gillam flying for Morrison-Knudsen contractors. During the first week of January 1943 he was assigned to fly five passengers from Seattle to Anchorage in a twin-engine Lockheed 10B Electra. Gillam flew through dense fog on instruments, and since Alaska was considered a war zone, maintained radio silence.

As it neared Ketchikan, the plane was struck by a downdraft, dropping 4,000 feet in the dark. Still flying full speed, Gillam swerved to miss a mountain. Seeing a break in the fog, he headed for it when suddenly his right wing struck a tree. After that the only sound was the hissing of hot engines in the snow.

Though the cockpit had crushed down on Gillam and he suffered a deep gash to his head, he managed to crawl out from the wreckage. He built snow shelters for the injured passengers from pieces of the plane, lit fires to warm them and gave them food. They could hear blasting from construction work on nearby Annette Island, but rescue planes could not find them due to the tree canopy. On the sixth day Gillam decided to set out and attempt to signal a rescue party.

When Gillam did not return, two of the passengers dragged two others down the mountainside to a better location near the shore. The fifth passenger had died, and they left her body by the wreckage. A Coast Guard patrol vessel spotted their signal fire along the shoreline.

Gillam’s body was found less than a mile away from the signal fire. He had wrapped himself in a parachute for warmth. There were signs he had broken through the ice of a nearby stream and then attempted to dry his clothes before laying down to rest. He never woke up.

For many, the death of No Kill ’Em Gillam brought a close to the golden age of the Alaskan bush pilot.

Mike Coppock has lived on and off in Alaska since 1985, working as an FAA flight specialist, general store clerk, teacher, editor, state park site manager and cultural interpreter at Denali National Park. Additional reading: Glacier Pilot, by Beth Day; Bush Pilot, by Arnold Griese; Bush Pilots of Alaska, by Kim Heacox; and The Flying North, by Jean Potter.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2021 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!