The apprentice airman could scarcely believe his situation. Yesterday he had been a supply truck driver with the Canadian Ordnance Corps. Today he was flying as an observer in the Royal Flying Corps, looking down from 10,000 feet on the zigzagging trenches of the Somme. Not only flying, but expected to fight the enemy from the front cockpit of an F.E.2b pusher biplane, part of a reconnaissance patrol heading into German-controlled territory. Incredibly, he had only flown once before, earlier that same day when he had been taken up to fire a Lewis machine gun at a can on the ground. Such was the pressing need in July 1916 for observer-gunners in the bloodied and battered RFC during the first Battle of the Somme.

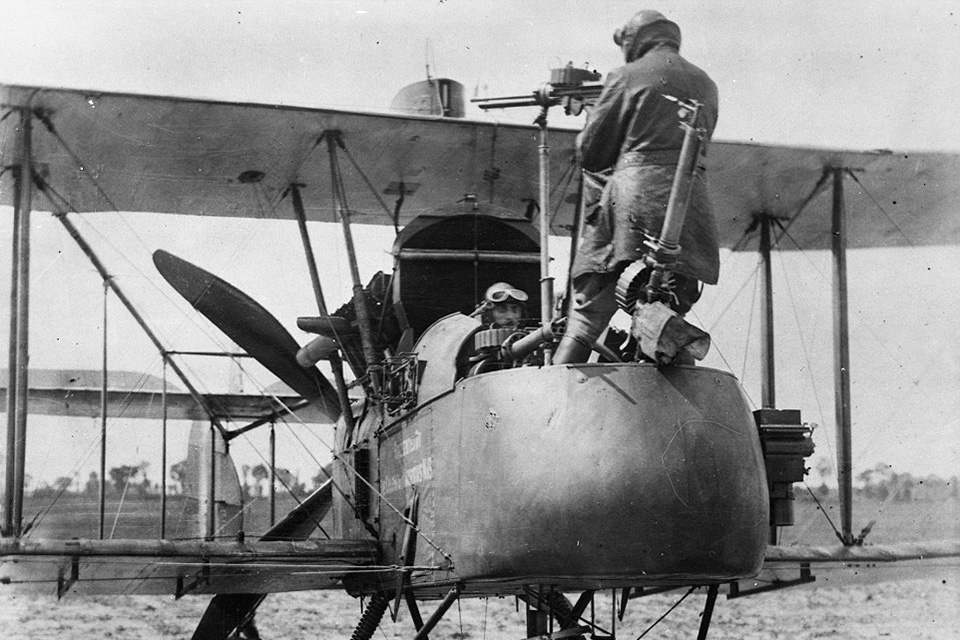

The novice observer had one Lewis in the F.E.’s exposed front cockpit, or “pulpit,” with another machine gun improbably mounted on a telescopic pole fixed just ahead of the pilot in his elevated rear cockpit. To use that gun, he first had to struggle to turn around in the 70 mph slipstream, then—with only the gun to cling to—balance precariously on his seat, legs braced against the plane’s structure, while firing rearward. All this in a violently maneuvering plane, without any seat belt or other form of restraint to keep him from tumbling out, and no parachute if he did.

Alert as they crossed the lines, the observer shifted from his seat onto his knees, unsure what to expect. A German aircraft appeared out of nowhere, giving off what the greenhorn airman at first took to be puffs of smoke. Tracers. Fighting back his fear, he began a frantic struggle to slot the forward Lewis into its swivel mount. Failing at the first attempt, he fell back cursing into the nacelle with the 26-pound gun on top of him. Upright again, he saw the German bank in front of him. Somehow he got the gun into position and opened fire without actually aiming, loosing all 47 rounds in one wild burst. Then came desperate fumbling to replace the magazine. By the time he looked up, the German had disappeared, leaving the F.E.’s wings peppered with bullet holes. As they headed home, he was surprised when the pilot reached forward to pat him on the head and shook his hand. Some quaint English custom, he guessed.

All was revealed after they landed. Ordered to report to the colonel, the observer was amazed to be congratulated and told that the German plane he fired on had gone down in flames. He had a confirmed victory on his first combat flight, and a rare bird at that, an Ago C.I two-seater pusher. Absorbed in changing the magazine, he had missed the Germans’ terrible end. It was July 15, 1916, and Private Frederick Libby, Canadian soldier and onetime American cowboy, had opened his score in spectacular fashion—on his birthday, no less.

Born in 1892 at the small cow town of Sterling in Colorado’s Platte Valley, Libby was at home in the saddle almost before he could run. After his mother died of consumption when he was 4, he was brought up largely by his father. Libby’s teenage adventures on horseback took him across the ranges from Mexico to Arizona to the Colorado plains, where he once spent many days trapped alone in a tiny sod hut while a great blizzard raged outside. Just after World War I broke out, when he and a friend found themselves in Calgary, Alberta, in September 1914, the restless Libby enlisted as a driver in a Canadian motor transport unit.

Shipped to France in April 1915 as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, he was soon involved in the grinding work of delivering supplies to the front. But he never actually saw combat in the trenches, for which he was unashamedly grateful. “Anytime I start feeling sorry for myself,” he wrote, “I always think, but for the grace of God I could be an infantryman.”

Even so, by July 1916 Libby had started to crave something more exciting. His opportunity came when a bulletin invited applications for transfer to the RFC as observers, initially on 30-day trials with the possibility of a commission if successful. Libby described his motives for transferring to the air service with typical candor: “Me, I’m not thinking of flying, but it might be a nice way out of this damn rain. I have no desire to be a hero either, living or dead, though if fate is kind, being a second lieutenant would be good as all second lieutenants I knew seemed to have it easy.”

Libby had scarcely applied when he found himself reporting to Major Ross Hume, commanding officer of No. 23 Squadron at Izel-le Hameau. After a brief introduction to the Lewis gun, he was kitted out in leather overcoat, helmet, goggles and gauntlets and given a trial flight on the morning of July 15. That afternoon he flew out over the lines for the first time as observer-gunner in an F.E.2b piloted by Lieutenant E.D. Hicks.

Fate would prove much kinder to Libby than to most of the chronically undertrained pilots and observer replacements then arriving from Britain. The hurried training program would be directly responsible for many of the appalling losses. This situation worsened as the balance of air superiority shifted away from the British with the arrival of new German single-seater fighter units and the establishment, in the early fall, of the first Jagdstaffel, or Jasta, of Albatros D.I and D.II fighters, with their two synchronized fixed machine guns. Meanwhile, there was no letup in the RFC’s unrelenting policy of carrying the fight to the enemy, giving the generally better-trained Germans the advantage of fighting over their own lines.

The Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.2b (Farman Experimental), or “Fee,” in which Libby so casually risked his life was much lower down the aeronautical evolutionary scale than the Albatros D.II. Based on an original design by Geoffrey de Havilland, the F.E.2b was responsible, along with the D.H.2 and the RFC’s other pusher biplanes, for effectively countering the “Scourge” of the Fokker E types, with their interrupter gear and machine gun firing forward through the propeller. (An F.E.2b crew had accounted for the German ace Lieutenant Max Immelman in his Fokker E.III on June 18, 1916.) Powered by a 120- or 160-hp Beard – more 6-cylinder inline engine that produced a maximum speed of just over 80 knots at sea level and a service ceiling of about 10,000 feet, it was scarcely a greyhound of the skies. But maneuverable and reliable it was. A potentially fatal defect the F.E.2b shared with other pushers was that during a serious crash its engine hurtled forward to crush the pilot.

After his initial taste of combat, Libby was put through a hurried course in the observer’s duties—aircraft recognition, photography and learning to drop 20-pound bombs. He practiced firing the Lewis in short bursts and also confronted the challenge of the rearward-facing weapon. “This gun is a nightmare,” he related, “nothing to hang onto except the gun, sticking up in the air anchored to a steel rod. A quick sideslip by your pilot would toss you so clear of the machine you would never get back.”

Official records show that Libby did not score again until August 22, 1916, by which time he had been commissioned a second lieutenant and transferred to B Flight of No. 11 Squadron, commanded by Major T. O’Brien Hubbard, at Bertangles. In his autobiography, however, he refers to a dogfight in late July while he was still with No. 23 Squadron, when he and his pilot and mentor, Captain Stephen W. Price, shot down “one beautiful Fokker monoplane. A quick burst of ten does it. His war is over, ours is just beginning. This was my second real engagement and my first real dogfight.”

On August 22, Libby and Price, who had transferred to No. 11 Squadron as B Flight commander, reportedly drove three Roland C.IIs down out of control south of Bapaume, all ostensibly at 1910 hours. At about the same time, however, Lieutenant Albert Ball— soon to become the RFC’s leading fighter pilot but then on his last day with No. 11 Squadron—was also credited with victories over three Roland C.IIs in the same area while flying a Nieuport 17 scout. Libby makes no mention of an encounter with three Rolands in his book, and the squadron history, while lauding Ball’s remarkable feat, includes no reference to its having been duplicated by the team of Libby and Price.

The pair were certainly airborne on August 22 as part of a large fighter group escorting several squadrons of extremely vulnerable B.E.2c reconnaissance planes converted into bombers. Attacked by a German flight, Libby opened fire using a Lewis fitted with a butt stock of his own devising. He recalled it was “like shooting fish with the front gun held firm by the shoulder…two bursts and he is upside down, then into a spin. But this was nothing. Almost to our lines, I catch a Fokker moving to come up under the tail of our upper back F.E.2b…I empty all forty-seven rounds into his middle. Two chances, two wins, two confirmed.”

Gradually the RFC was losing the upper hand as the reequipped German Jastas, under leaders like Captain Oswald Boelcke, took their remorseless toll. “Our casualties are bad,” Libby noted. “Every night at dinner there are always new flyers in our mess, taking the places of our lost ones killed in action or prisoners of war. Every week Boelcke has one of his pilots drop over a list of our fellows who are prisoners and also the names of the ones who are wounded or killed. Damn decent chap, this Boelcke.”

Meanwhile, although not yet a qualified observer, Libby had been appointed squadron gunnery officer and put in charge of training new observers. Of his own status as an American in the RFC, he commented: “I am a sort of curiosity. Everyone treats me wonderful, but still wonder why I am here.” Regarding his British colleagues, he confided: “Every day we are taking a licking, but every day we go back for more. One has to admire these English boys. With barely enough experience to fly a ship, they sail into Boelcke and his gang like old timers. They are short on experience but long on courage. I’m real proud to be one of them.” But worse was yet to come for Libby and the “English boys.”

Price and Libby sent an Aviatik C down out of control on August 25 and another on September 14, the day before the third phase of the Battle of the Somme began. This fifth victory made Libby the first American ace of the war, albeit not as a pilot. On September 17, however, the squadron suffered a devastating blow when Boelcke’s Jasta 2, flying their new Albatros D.IIs, shot down four of its aircraft. Two B.E.s they were escorting were also lost. A Fee flown by Lieutenant L.B.F. Morris and Lieutenant T. Rees, both of whom were killed, became the first victory for a new member of Jasta 2, Lieutenant Manfred von Richthofen. Libby, although not directly involved, was dismayed. “It is the worst defeat we have ever suffered,” he wrote. “Now with Mr. Boelcke and his new and faster machines, we will really catch hell.”

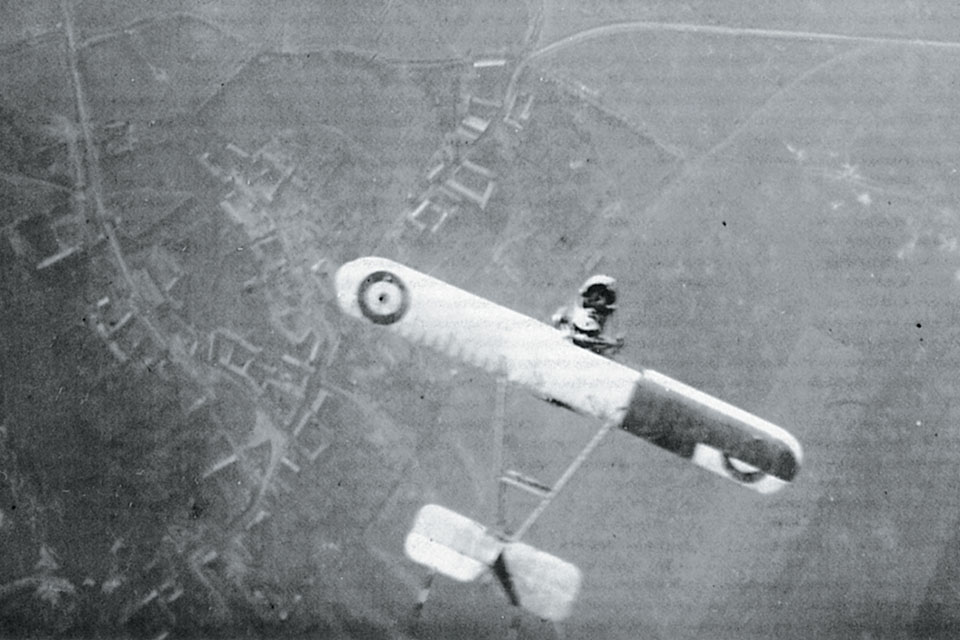

Two days later, a No. 11 Squadron reconnaissance flight and its No. 60 Squadron escort were attacked near Quéant by Jasta 2 to such shattering effect that the operation was abandoned. Soon after the mystified crews found themselves patrolling some 15 miles behind their own lines for four days—as they later discovered, because of an imminent visit to the wing by King George V. Libby quipped: “Here is the fellow I have been doing my best to keep well all these months on Thursday evenings (the loyal toast) and other days as well. He looks healthier than I.” Cowboy and king would meet again.

Libby and Sergeant Thompson downed an enemy fighter near Logeast on September 22, a day notable for the heightened activity of the increasingly confident German airmen crossing the lines. Four days later, with 50 hours over the lines, Libby officially qualified as an observer, entitled to wear the winged “O” brevet.

Price and Libby downed an Albatros D.I near Mory on October 17, after B Flight was bounced by a gaggle of Rolands and Albatroses while returning from a photorecon mission. Of this furious encounter, Libby recalled: “When the attack comes, Bogart [Rogers, another American volunteer] and a new observer to our back each get one of the diving Hun ships. I think I crippled a third, but one of our escorts is hit in the petrol tanks and is aflame. There is nothing we can do but keep going. We are hit by another flight from higher up. This time I am sure of one and my friend Bogart gets another.” B Flight lost two Fees in that engagement, with only one crewman surviving as a POW.

The last victory by Price and Libby was over an Albatros D.I near Douxcette-Ayette on October 20. Their partnership ended in early November, when Libby went to England for pilot training and Price assumed command of a training squadron at Gosport. They were reunited at Buckingham Palace in London on December 13, when King George invested them with their MCs.

Libby summed up his time with No. 11 Squadron: “I have been lucky and I am still alive….Of all the officers I first knew, only a few are now living. The British have given me credit for ten enemy planes confirmed and eleven probables. This only means I have been lucky and am still alive. One true thing I have found about being a flyer in the RFC is the greatest feeling of good fellowship I have ever known. Just to be a member in any capacity is an honor.”

Official figures for the period illustrate just how fortunate Libby was to survive this especially bitter chapter in the aerial conflict. By mid-November 1916, the RFC had lost 308 pilots killed, wounded or missing over the Somme, while 268 others had been sent home—a total of 576 from a force that had begun the battle with 426 pilots. By this time the life expectancy of RFC aircrews had fallen to one month, a critical hemorrhaging of experience.

Libby, who had already received some flight training from Price, officially qualified as a pilot on March 5, 1917. Characteristically he wrote: “Though this is what I have been working for, still the thought of not having my observer’s wing when I have been so lucky doesn’t seem right….Hell, my observer’s wing was a hundred times tougher to get than the pilot’s, and having been an observer has made the pilot training a breeze.” Thereafter, he always carried his observer’s wing in his pocket.

After advanced flight training, Libby was posted on April 18 to No. 43 Squadron at Treizennes and later Auchel. The squadron was commanded by Major William Sholto Douglas and equipped with the Sopwith 1½- Strutter two-seater, powered by a 130-hp Clerget rotary engine. The “Strutter,” although by this time nearly obsolete, was the first British aircraft designed to incorporate a synchronized machine gun and innovative features such as a variable-incidence tailplane and airbrakes on the lower wing. Libby took to it immediately.

His return to the front, during the Battle of Arras, coincided with a series of disasters that came to be known as “Bloody April.” Between April 4 and 8 alone, the RFC lost 75 aircraft in combat, many victims of German Albatroses, with Richthofen, now commanding Jasta 11, accounting for 21 British aircraft during the month. No. 43 Squadron, with 32 pilots and observers, suffered 35 aircrew casualties, many of them raw replacements shot down within days of their arrival. This was the high point of German aerial supremacy, as a new generation of British fighters—Bristol F.2b, S.E.5 and Sopwith Camel—gradually re – gained the dominance that they and their French allies would retain until war’s end.

Libby achieved his first victory as a pilot on May 6, when he destroyed an Aviatik two-seater. The squadron history recounted: “On a later patrol Second Lieutenant Libby (pilot) and Lieutenant J L Dickson (observer) when just south of Avion at about 4.30 pm fired on a hostile machine at 200 feet. After twenty rounds the machine was seen to dive away. Ground observers reported that the hostile craft had crashed at Petit Vimy.”

Libby was soon busy with an important recon assignment. The squadron history stated: “A very useful reconnaissance was carried out on 27 May 1917 by Second Lieutenant F Libby, who set out with Lieutenant F H Jones as observer at 1.15 pm, returning to Auchel two hours later. Considerable information concerning the positions in the area to the east of and around Lille was picked up from a height of 14,000, from which eighteen photographs were taken.” At 14,000 feet the Strutter would have been at the very limit of its ceiling, its crew frozen and desperately short of oxygen. By Libby’s account, on that sortie Jones “knocked off a Halberstadt scout,” though it was not confirmed.

As counselor to all probationary observers, Libby took under his wing a young infantry officer just transferred in from the trenches. Lieutenant W.S. “Babe” Cattell had a problem, as Libby described: “Cattell is an excellent shot with a machine gun on the range, but the minute he is in the air he becomes deathly ill. He vomits all over the ship and loses interest in the target and the world in general.” Libby persevered. How well he succeeded can be judged by the entry in the squadron history for June 1, 1917: “While over Cuinchy, Second Lieutenants F Libby and W S Cattell, observer, observed our AA batteries firing at a hostile machine. They immediately attacked and the enemy was last seen going down east of La Bassee.”

In appreciation for Libby’s efforts, Cattell presented him with a large American flag, which the new commanding officer, Major Stanley Dore, suggested he cut into streamers, “just to show the Hun that America had a flyer in action.” From then on, Libby always flew with the Stars and Stripes attached to the wings of his aircraft.

While Libby was kind to fledgling observers, he could be scathing about fellow pilots he suspected of “shooting a line.” In a clear allusion to No. 60 Squadron’s Billy Bishop, whose controversial June 2 solo attack on a German aerodrome earned the Canadian ace the Victoria Cross, Libby wrote: “We have one pilot in our wing who writes a wicked report….It seems early in the morning, before anyone else was up, he has his plane wheeled out, goes over to a German airfield and routs the Hun out of their beds, strafes the hangars and waits for Mr. Hun to come up. The first two off the ground he knocks off, then gets two more trying to get off. The next two, he chases into a tree and leaves them there like Santa Claus, then destroys two more, so home to breakfast. God Almighty! Excuse me while I vomit.”

On June 7, the squadron history noted approvingly that Libby and his observer, 2nd Lt. E.W. Pritchard, had attacked a German convoy near Warneton, then machinegunned troops in the area “with marked effect.” Libby had no doubt of their fate if they fell into the hands of their targets: “To be shot down and captured by the German Air Corps is not too bad, but to come down close to the lines where the German infantry can get their hands on you is curtains. They shoot you quick and find a reason later.”

Libby and Pritchard downed an Albatros D.III northeast of Lens on July 23. Two weeks later, Libby was promoted to captain and transferred as B Flight commander to No. 25 Squadron, also at Auchel, equipped with D.H.4 bombers. He scored two further victories in August, both with 2nd Lt. D.M. Hills.

The American’s remarkable RFC career ended in September 1917 when, at the request of Colonel Billy Mitchell, he was transferred into the U.S. Air Service. After a fundraising tour, highlighted by the auction of his Stars and Stripes wing streamers for Liberty Bonds at Carnegie Hall in New York City, he was assigned to the 22nd Aero Squadron at Hicks Field.

Unhappily, a spinal disability ended Libby’s flying career and troubled him for the rest of his life. Nevertheless, this remarkable man raised a family in California, made and lost fortunes in oil exploration and celebrated his 65th birthday with a flight in a supersonic U.S. Air Force jet.

Nor did the British forget Libby. In 1963 his former CO, Sholto Douglas, by then Marshal of the RAF and Lord Douglas of Kirtleside, recalled in his memoir Years of Combat: “An American youngster by the name of Frederick Libby, who had disguised himself as a Canadian, joined me at Treizennes as a pilot in No. 43 Squadron at the time of the Battle of Arras. Libby served with the Royal Flying Corps during the worst period in our fortunes and one afternoon not long after coming to us he shot down his first enemy aircraft which crashed just to the east of Vimy Ridge.”

Captain Frederick Libby, MC, America’s first ace and the first man to fly his country’s flag over German lines, died in Los Angeles on January 9, 1970, at age 77.

Derek O’Connor, who served in the RAF, writes from Amersham, Bucks, England. For further reading, he recommends Libby’s entertaining autobiography, Horses Don’t Fly, with the caveat that it was written largely from memory in retirement, and therefore it is sometimes chronologically wide of the mark.

Originally published in the July 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.