In July 1968, 75-year-old Bruce C. Hopper looked back on his life with satisfaction…and a measure of disbelief. “My power to survive continues to astonish me,” he remarked. Hopper told a gathering of fellow Harvard University alumni that his “long record” of close calls had begun in World War I when, in his mid-20s, he served as a bomber pilot with the U.S. Army Air Service (USAS) in northeastern France. He said that in July 1918, for instance, he had somehow managed to survive the crash of his Sopwith Camel and was plucked from the wreckage by a doctor armed with a pair of pliers. He was briefly hospitalized but refused to be sent home and instead returned to the battlefield—“not from an eagerness for air combat but from a natural desire to stick with the gang.”

Over the next several months, Hopper flew 29 bombing missions as a flight leader of the Army’s 96th Aero Squadron “Red Devils” and was later awarded a Pershing Citation and a Croix de Guerre for his service.

Born on August 24, 1892, in Litchfield, Ill., Hopper spent his childhood in Billings, Mont., where his father was a rancher. In 1913 he enrolled at the University of Montana. But after two years, he and his friend and fellow sophomore Verne Robinson were bitten by a combination of “wanderlust and worthy purpose,” according to an article in the Great Falls Tribune. Soon the pair was making arrangements to join the American Red Cross in war-torn Europe.

Hopper put his plans on hold, however, when he was offered a scholarship to attend Harvard University. After less than two years at Harvard—with the United States having entered World War I in support of France, Great Britain and Russia—he decided to leave his studies and head to Europe on his own.

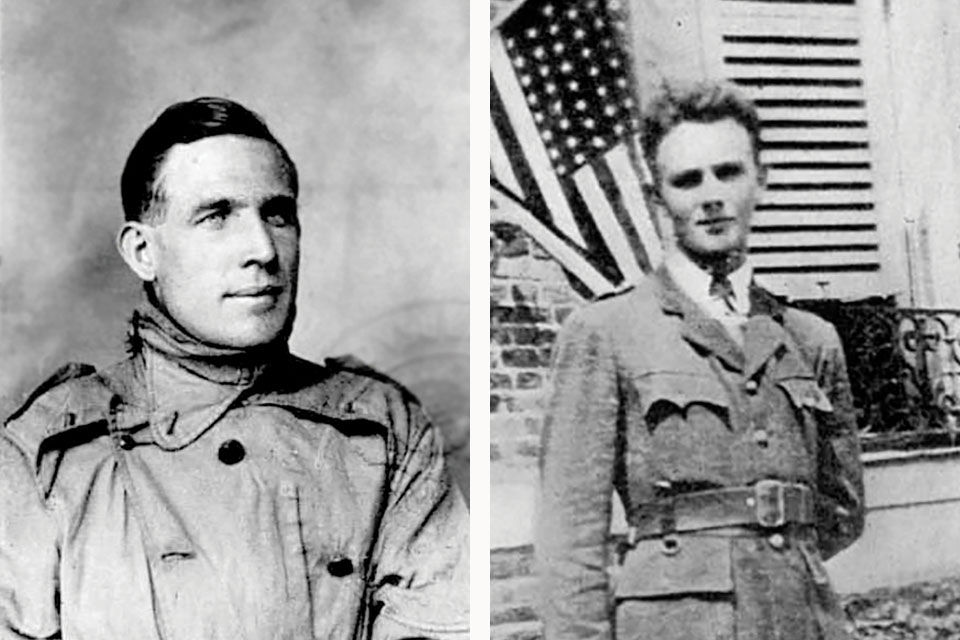

On April 28, 1917, little more than three weeks after the U.S. declared war on Germany, Hopper boarded the French liner SS La Touraine in New York, bound for Bordeaux, France. During the trip he befriended three students from the Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass.—Jack Morris Wright, William Taylor and Jack Sawhill—who, like him, were traveling to France to volunteer for service in the war. Once in France, the four men, calling themselves the “Four Musketeers,” joined the motor transport branch of the French army and were assigned to haul military equipment and personnel with Motor Transport Unit 526 (Réserve Mallet) along the Soissons and Reims fronts.

Hopper later said he was particularly fond of Wright, who was born in the U.S. but raised in France, noting they both shared a deep love for education. In an introduction to a collection of Wright’s letters home from Europe, published in 1918, Phillips Academy principal Alfred E. Stearns said that his student’s love of the French had led him to enter into their “great struggle.”

“I am sure I can help them,” Wright had told Stearns, “and I owe them so much.”

Once in France, Wright wrote to his mother saying he was driving a five-ton Pierce Arrow truck to and from the front and eating bread and cheese, “with guns flashing next to me…while sitting on a truck load of ten thousand pounds of dynamite.” On June 11, 1917, he said in a letter to his aunt that he had also seen airplanes “fall to their death” and had “heard the wounded cry.”

Despite the risks, Wright decided to join the USAS, training as a pilot. “It is a dangerous service,” he wrote to his mother. “Many do not come back….You’ll no longer have a son in the truck service, but a son in aviation.”

At about the same time, the other members of the Four Musketeers—Hopper, Sawhill and Taylor—also signed up to become pilots. Initial flight training for them and others took place at a complex of French military airfields near Tours, later known as the 2nd Air Instruction Center.

“We came to Tours together and learned to fly,” Hopper wrote in a letter to Wright’s mother, Sara Greene Wise, a well-known artist at the time. “Jack realized more than most of us the larger significance of flying….Flying was so tremendous in reality, so supernatural, so akin to some divine privilege….He told me he always felt as though invisible hands of a cosmic giant were supporting the frail wings of linen and wood, as on he rushed with the gripping power of the propeller.”

In early September 1917, after his first flight at Tours (with an instructor at the controls), Wright wrote to his mother saying that “you realize [you are] hanging in space by two thin wings and slowly progressing by the deafening motor and mad propeller…[and] that the space you are floating in is a breathing medium—a vast, colossal god in whose arms you are lying as a speck in the infinite.”

The next day, Wright was allowed to take the controls. But he came down, he said, “with the conviction that I could never make an aviator…I felt myself impossible to ever be able to hang correctly in space and tend to all the necessaries at once, when at the slightest mistake you were finished.” That night he slept restlessly, thinking that the next time he would climb into the airplane and “swing that machine around to the gale as I pleased, making myself at home and sure, or that I would, in attempting it, break my neck. I was bent on flying or nothing.”

As the sun came up the following day, “I got in [the plane], we tested the motor, and off,” he wrote his mother. “The sun shone bright and I said to myself as though in a hammock, ‘Fine day today; the country will look pleasant. We’ll enjoy the trip. Ah! We’re up. I was getting bored with the earth!’ I waited for the signal. Finally, at two hundred meters after passing over another plane, my pilot tapped me on the back. I took the controls and calmly remembered what I was [supposed to do]….The weather was calm—no ‘bumps’—no ‘pockets.’ I was running the old boat as I had intended to—like a man. When the trip was over, the results were accomplished. Between confident running of the plane or smash-up, I had gained the former—and, believe me, how I did enjoy it. Now I must go ahead, for I have much to learn and resist and conquer, inasmuch as I intend to make an aviator.”

But along with his sense of excitement were persistent thoughts of his possible demise. “[D]eath is the general joke of the day; it makes us laugh….it is there—always present.”

His roommate and fellow Musketeer Hopper later wrote that Wright’s “naive curiosity” had prompted him again and again to “stunt” with his airplane long before he was a master of the controls. Hopper said that at the advanced flight training school at the Issoudun aerodrome, about 150 miles south of Paris, a rivalry had sprung up between Wright and Jack Sawhill as to who would make the most rapid progress toward winning the much-coveted French brevet.

“One day [Wright] circled the field counter-traffic, that is he turned to the right on the take-off when the two balls at the pilotage indicated compulsory turning to the left,” Hopper noted. “For that error he was taken off the flying list for two or three days, much to Jack Sawhill’s delight. Jack Sawhill, however, landed crosswind the next day, and was given a similar punishment. This friendly rivalry continued till Jack Sawhill fell in a Nieuport, and was taken to the hospital with a broken arm.”

On January 16, 1918, Hopper said goodbye to Wright at Issoudun before heading back to Tours to become a flight instructor. “[I said] I should meet him in Paris, or at the front, or Julybe behind the moon….[But] his rendezvous was not with me, but with Death.”

Hopper wrote to Wright’s mother a few weeks later that on January 24 Wright had spiraled down from a height of 1,000 meters “with a cold motor” only to find that he was gliding short of the field. Wright tried to lengthen his landing angle but according to Hopper he flattened out at 50 meters altitude, the plane stalled and it “wing-slipped” to the ground. Wright was killed in the crash.

Just two days before the accident, Wright had written to his mother saying that he had been practicing spirals near the airport, which he found frightening: “[Y]ou’re hung up in space some three thousand feet when you cut…the motor and start,” he wrote. “I pulled the plane over on a perpendicular and down [and pulled] back a little on the stick to make her spin lightly, and off she went, the clouds whirling by as in a cyclone—a war of the gods and the wind roaring at me like a continual fog-horn and pulling on me hard.”

Wright continued: “Round like a top, down, down towards the earth, as in a falling merry-go-round the plane led me like a bolt through space. I remember vaguely acknowledging that if the bus did smash, it was nevertheless a great experience, and [it] was the height of the game.”

After landing, he immediately took to the sky for a second attempt. “My second, I felt was better, so that when I came out of it, it was as though I had held my breath under water a long time. I just burst loose and sang and shouted at the top of my voice.”

Wright told his mother that, between attempts, he had seen the deadly crash of another student pilot he knew. “I don’t feel heart-broken for him,” he wrote, “so much as for the mother back home.”

As for the fate of the other two Musketeers, Sawhill’s broken arm never fully healed and after a lengthy hospital stay he returned to the U.S. at war’s end. Bill Taylor completed his flight training and joined the 95th Aero Squadron, but was killed in action on September 17, 1918.

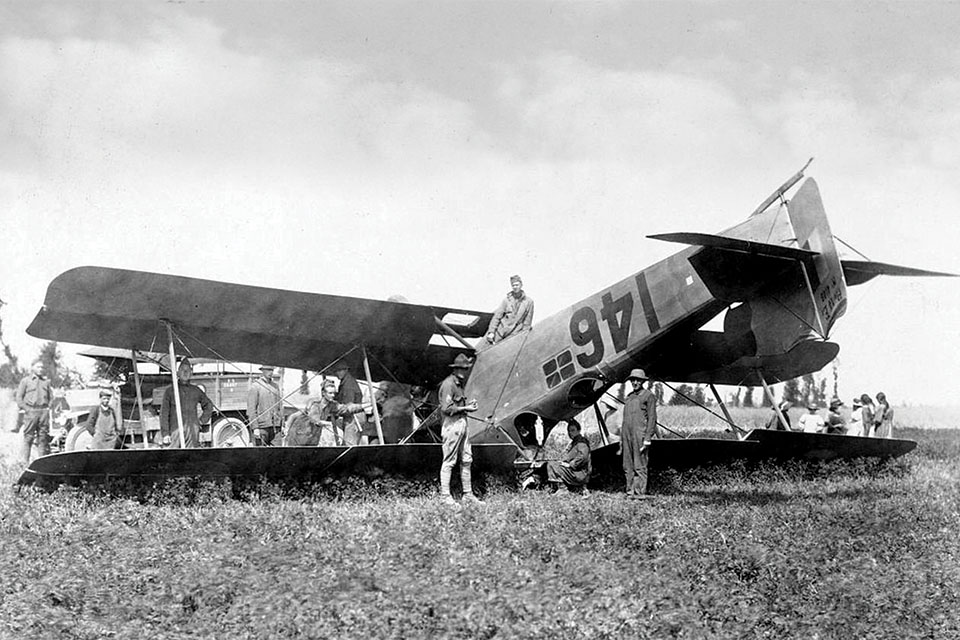

Hopper would spend the remainder of the war as a lead bomber pilot with the 96th Aero Squadron, flying the Breguet 14.B2 from the squadron’s base at Amanty Airdrome, near the front. Initially, in the spring of 1918, the squadron had to make do with 10 old Breguets that were in constant need of major repairs. “It was impossible to get spare parts,” Hopper wrote. “The squadron mechanics, when ordered to get the Breguets ready for duty over the lines, were forced to utilize worn out farm machinery discarded by peasants in the vicinity of the airdrome.”

On June 12, the 96th conducted its first bombing mission of the war when it attacked the railroad yards at Dommary-Baroncourt with a formation of six Breguets. The Americans dropped nearly a ton of bombs during the four-hour raid, leaving a trail of explosions across the yards and an adjacent warehouse.

But on July 12 the squadron suffered a major loss when six Breguets were forced to land in enemy territory due to adverse weather and poor navigation. The pilots and observers of all six bombers were captured, including Major Harry M. Brown, the 96th’s commanding officer.

Hopper wrote in a postwar report titled “Tactical History of American Day Bombardment Aviation” that after the debacle, which left the 96th effectively without aircraft, bombing operations ceased until early August, when 11 new Breguets were delivered to Amanty from Colombey-les-Belles. Twenty raids were conducted, Hopper said, and 21.1 tons of bombs dropped during two weeks in August. He said the raid on Conflans on August 20 was particularly successful: 40 German airplanes were destroyed on the ground and 50 workman and soldiers were killed.

Hopper also participated in a number of successful bombing missions over the next few days, including those targeting the railroad yards at Longuyon and Audun-le-Roman on August 21 and Conflans on August 22, 23, 25 and 30 and September 3.

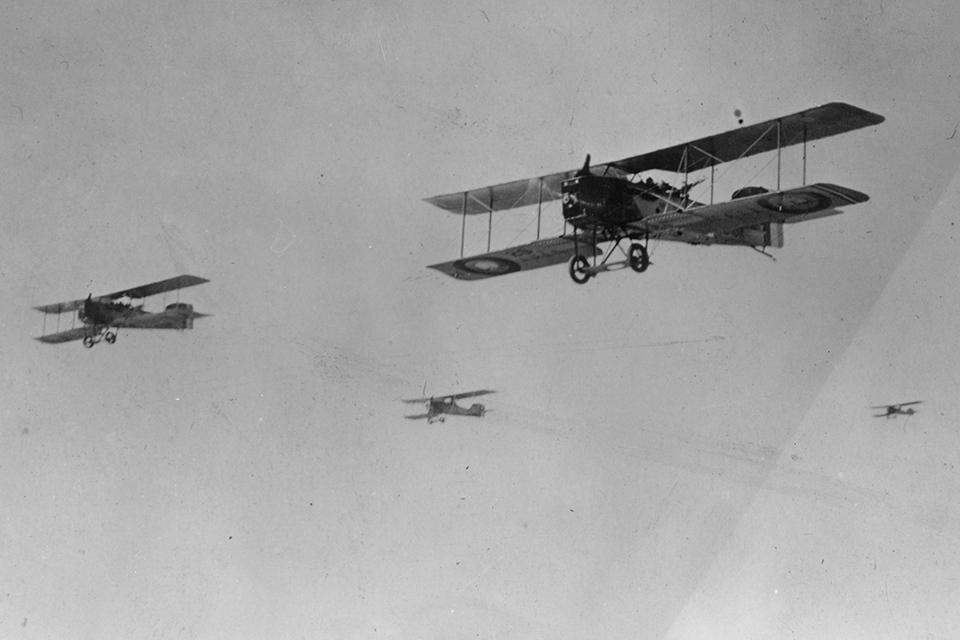

At the same time, Colonel William “Billy” Mitchell, commander of the First Army Air Service, was moving his headquarters to Ligny-en-Barrois, a few miles from the front, in preparation for a major Allied assault on the German defenses—the St. Mihiel Offensive. From there, he would command the largest aggregation of air assets engaged in a single battle during the war, involving roughly 1,500 aircraft in support of 550,000 American and 110,000 French troops on the ground.

According to Hopper, the day that the offensive began—Thursday, September 12—was “the worst flying day in many months.” A strong southwest wind made formation flying extremely dangerous, he wrote, and low, fast-moving clouds made it impossible to see more than a mile and a half ahead. The weather improved in the afternoon, however, and the 96th was able to conduct three missions—with disastrous results. Eight planes were wrecked or put out of commission, and three members of the 96th were killed.

The results over the next few days were not much better. The squadron scored a perfect hit at the neck of the railroad yards at Conflans and successfully bombed enemy troops on the roads between Vittonville and Arnaville on the Moselle River. But according to Hopper the 96th lost no fewer than 16 fliers over the course of the four-day St. Mihiel operation along with 14 airplanes that were either destroyed in combat or forced down in hostile territory.

During the final Allied assault of the war, however, from September 26 until the Armistice of November 11, 1918, the 96th recorded a series of major bombing successes as part of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

“For the first time since the squadron had been operating,” Hopper wrote, “the pursuit planes cooperated closely with the bombers. The protection afforded by the pursuit planes…[was] of immense value for precision bombing.”

Hopper said that larger formations, comprising up to 20 airplanes, were also employed by the 96th over Meuse-Argonne. “The success of the big formation…did more to raise the spirits and courage of the squadron than any incident in its history,” he recalled.

One of the first successes of the new-style formation occurred on October 1 when Hopper led 13 planes on a bombing mission over Banthéville. On October 18 a flight of 14 aircraft led by Hopper reached its objective, Sivry, dropping 1,600 kilograms of bombs on the town center and near-by roads. “According to intelligence reports from French sources,” he noted, “250 men were killed, and 700 wounded on this raid.”

Immediately following his discharge from the USAS in 1919, Hopper wrote a history of the 96th Aero Squadron, which he later said was “a pathetically small manuscript because there was just one log book as a record.” He then teamed up with an Army buddy, Cass Canfield (who later served as president and chairman of Harper & Brothers publishers), to travel the world. The pair floated down the Nile River in a felucca, camping at night on the riverbank. They traveled across China on foot and by raft and sampan for three months in 1920-21, ending up in Shanghai, where Hopper spent a year writing editorials and a column for the China Press and Shanghai Evening Star.

Hopper also wandered through the Urals dressed as a peasant. With Junius B. Wood, a correspondent for the Chicago Daily News, he traveled to Murmansk and inland to Luvozero by reindeer-drawn sled.

In 1924 he returned to Harvard to complete work on his bachelor of science degree, followed by a master’s degree in 1925. He spent two years in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1929 as a fellow with the Institute of Current World Affairs and completed work on his Ph.D. at Harvard in 1930, joining the faculty as an assistant professor of government. Among his students over the years were three Kennedy brothers: Joseph P., John F. and Edward M.

In March 1942 Hopper established a branch of the Office of Strategic Services—precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency—in Sweden, where he observed and interpreted Soviet activities in the Baltic region for about a year. He later served as chief historian for the U.S. Eighth Air Force and U.S. Strategic Air Forces and subsequently worked at the Pentagon as special consultant and speechwriter for General Carl A. Spaatz.

In 1946-47 Hopper served as a member of the site selection board for the U.S. Air Force Academy. He then returned to Harvard, where he spent the next 13 years, until his retirement in 1961, as an associate professor specializing in Soviet affairs. He died at age 80 in Cambridge, Mass., on July 6, 1973.

Gary G. Yerkey is a former foreign correspondent for several U.S. media outlets, including Time-LIFE and the Christian Science Monitor. He currently works as a journalist and author based in Washington, D.C. Further reading: Hostile Skies, by James J. Hudson; Destiny’s Wings, by Hugh T. Harrington; A Poet of the Air, by Jack Morris Wright; and Wings of Honor, by James J. Sloan Jr.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!