Glowing object that streaked across Connecticut sky in 1807 puts a young nation on the scientific map

AS A QUIET WINTER’S NIGHT in the Northeast was nearing its end, light blazed in the darkness. At half past six on the morning of Monday, December 14, 1807, a fiery mass traversed the sky north to south, rocketing into and out of sight in 30 seconds. In Wenham, Massachusetts, a woman named Gardner wondered “where the moon was going.” In Weston, Connecticut, Judge Nathan Wheeler was making his usual early morning survey of his farm when “a sudden flash…illuminated every object.” The jurist looked up to see “a globe of fire just then passing” followed soon after by three loud reports and lesser rumbles whose reverberations suggested a “cannonball rolling over a floor.”

A meteorite had exploded overhead, rattling residences in New Milford, Connecticut, 20 miles away. Fragments of space debris rained on then rural Weston in the state’s southwest corner. One stampeded a dairy herd. Another chunk buried itself a meter deep.

The Weston Fall, the first meteorite documented to have landed in the United States fascinated locals and their president, Thomas Jefferson. The meteorite strike deep in Connecticut also put American science on the world map.

The United States of the early 1800s was a scientific backwater much condescended to by Europeans. “Among civilized nations…few have made less progress in the higher science…than the United States,” wrote Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America. The young country boasted a few first-class scientific minds, like Benjamin Franklin. A founder of the American Philosophical Society, a center of scientific study, he theorized that meteorites might come from space—a crazy notion, according to many fellow citizens. The ancient, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and Chinese had noted the phenomenon, sometimes regarding it as an ill omen.

“Meteorite” derives from the Greek for “thing in the air.” As far back to 2,300 BCE, observers in southern Iraq had noted how a meteorite left a two-mile crater. By the Renaissance, however, the Vatican had decreed it heresy to claim stones fell from heaven because that suggested that God’s creation was less than perfect. This tension between believers and scientists has waxed and waned but never gone away and remains strong even today.

Enlightenment thinkers initially hypothesized that meteorites were volcanic projectiles, a theory adjusted to locate the presumed eruptions as coming from the moon. Another thesis held that lightning in clouds fused dust particles into three-dimensional lumps, like geological hail.

An 1803 meteorite fall at L’Aigle, France, got sky watchers rethinking meteorites’ origin because so many people saw the event. Analyzing meteorites’ makeup, European chemists discovered the objects’ geology differed from Earth’s, lending credence to the theory these projectiles were not of this world.

The Weston meteorite caused a sensation. Reported the Connecticut Herald, “The meteor which has so recently excited alarm in many and astonishment in all” brought with it the “apprehension of some impending catastrophe.”

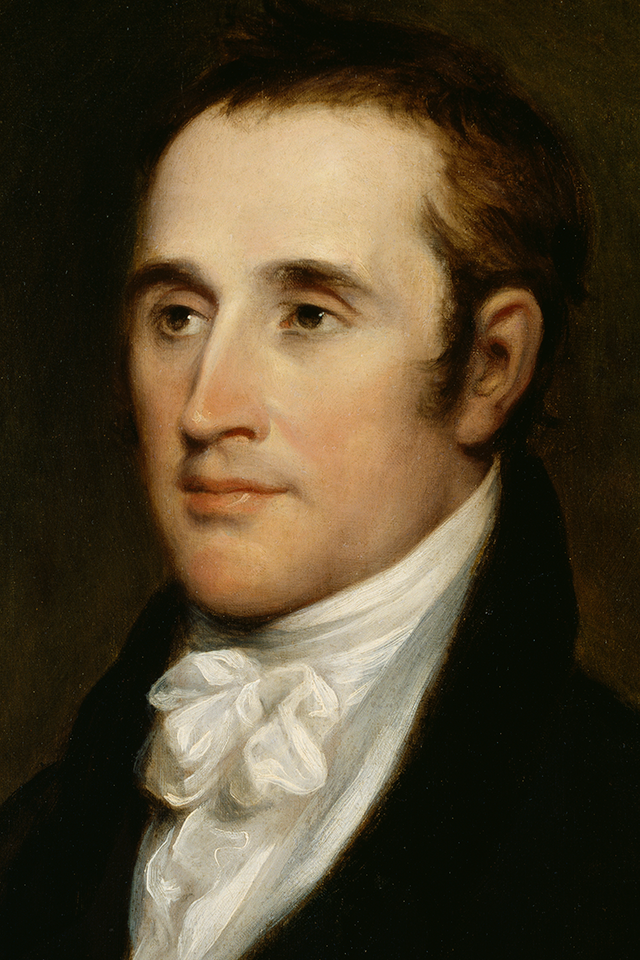

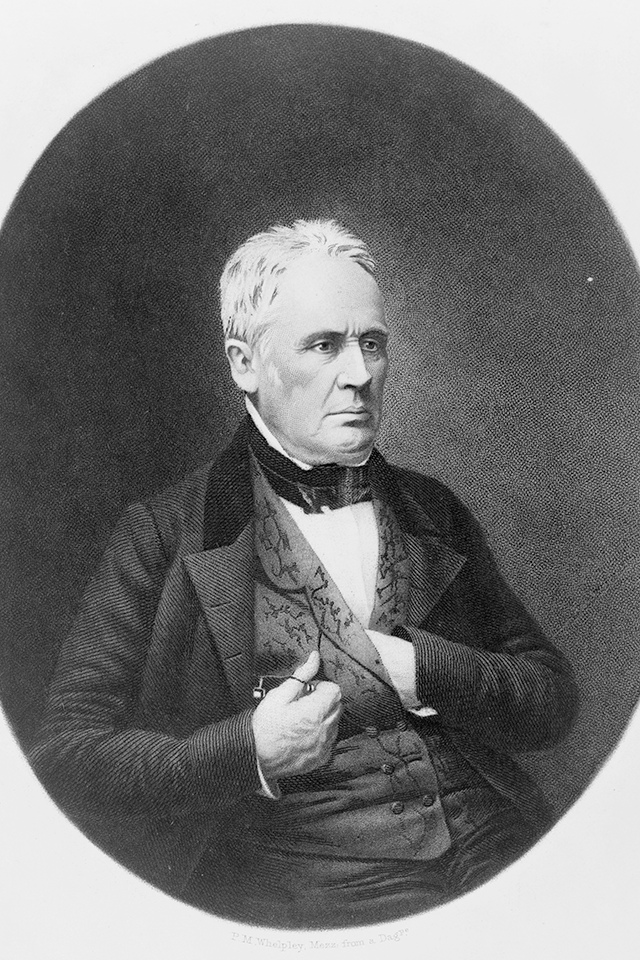

Benjamin Silliman, 29, was tapped to investigate the mystery object. A professor of chemistry at Yale College in New Haven, Silliman was the son of a farmer who had fought alongside George Washington in the Revolution. He was a native of Fairfield, a coastal town a few miles away.

Founded in 1701 to educate young men in theology, Yale College—“university” came in 1887—was one of the first schools in New England to schedule classes in “chymistry.” Shortly after Silliman graduated in 1796, Yale’s progressive president, Timothy Dwight, picked him to expand science curricula at the institution, at the time no center of science compared with Boston and Philadelphia. To learn chemistry, Silliman went for a year of advanced study in Philadelphia, London, and Edinburgh. He returned to Yale in 1806 as the college’s first professor of chemistry and natural history.

Silliman, tall and handsome with dark hair and dark eyes, was known for his gracious manner and integrity; his undergraduate nickname was “Sober Ben.” And though he worshipped at the altar of logic he held strong Christian beliefs. There was little chance of him upsetting Yale’s theological applecart since he could appreciate both science and faith.

Silliman made it his business to investigate the Weston Fall after receiving a letter from Dr. Isaac Bronson, a friend and physician from nearby Greenfield who had witnessed the flame in the sky. Energized, Silliman, conversant with “meteorites and the phenomena that …attended their Fall,” immediately “broke off every…engagement and immediately resorted to the scene of this remarkable event.”

Treading lightly, Silliman invited fellow Yale Professor James L. Kingsley to join him in the enterprise. Kingsley was an astute choice. A classical scholar with knowledge of ecclesiastical history, Kingsley bore himself with religious faith that would balance Silliman’s rationality should their findings stir controversy.

The two left New Haven by chaise the morning of Saturday, December 19, arriving later that day in Fairfield. Honoring the Sabbath by not traveling, they made Weston Monday morning December 21, eight days post-facto—in that era, swift. Weston had changed little since colonial times. Heavily forested, hilly, marked with granite outcroppings and rutted roads, the town was one of Connecticut’s poorest and most isolated. Its 2,500 residents were subsistence farmers mainly growing onions and beets in fields so rocky plowmen referred to cobbles as “New England potatoes.”

The fall was the talk of Weston. William Prince had been asleep when a hunk of meteorite buried itself within 25 feet of his house. He went outside but saw nothing and assumed he had heard a lightning strike. Learning of the meteorite at a town meeting that day he looked again, finding a “noble specimen…two feet from the surface.” Prince sold a 12-lb. fragment to Bronson; it was the source of the sample sent to Silliman.

Bronson introduced Silliman and Kingsley to townsfolk who led the men to six of the seven sites struck by fragments along a line six to ten miles long roughly matching the flaming object’s trajectory. A piece that was estimated to weigh 200 lb. plowed a 100-foot trench.

Farmers knew their land well enough to recognize disturbed spots, making it easy to find some strike zones, such as one crater a foot wide and two feet deep. And meteorites, usually blackened by heat, contain a disproportionate amount of iron, making them heavy.

Merwin Burr had been standing near his house when a chunk weighing 20 to 25 pounds struck a boulder 50 feet from him. The impact so pulverized the falling piece, he told Silliman, that the largest fragment “did not exceed the size of a goose egg [but] was…still warm to [Burr’s] hand.”

Emulating the entrepreneurial Prince, a few Westonians put a price on their finds. Silliman had to purchase at least one specimen “for it had now become an article of sale,” he noted. “It had pleased heaven to rain down this treasure…and they would bring their thunderbolts to the best market they could.” Others held onto their heavenly souvenirs, “impressed with the idea that these stones contained gold and silver.”

That wish did not pan out. For two days Silliman and Kingsley tramped the woods lugging sample boxes, scales, compass, and notepaper. Silliman took measurements with which he hoped to calculate the meteorite’s weight, trajectory, and rate of descent. “We visited and carefully examined every spot where the stones had…fallen, obtained specimens [and spoke] with all the principal witnesses,” he wrote.

Silliman deemed the account by Wheeler, a justice on the court of common pleas, as the most trustworthy of those he heard, characterizing Wheeler as “a gentleman of…undoubted veracity, who seems to have been entirely uninfluenced by fear or imagination.” Silliman and Kingsley missed at least one fragment, a 36.5-lb. piece that was sold, to Silliman’s disappointment, to Colonel George Gibbs, a wealthy mineral collector from Newport, Rhode Island. The largest sample Silliman obtained weighed six lb. He and Kingsley returned to New Haven to analyze their space bits.

To satisfy public interest—and perhaps to stake a claim on academic immortality—Silliman rushed into print a two-part letter on his preliminary findings. The first portion appeared December 29 in the Connecticut Herald and was reprinted by other papers. Everyday Americans were not alone in wanting to know more about the stone from the sky. Coverage spread to England and France.

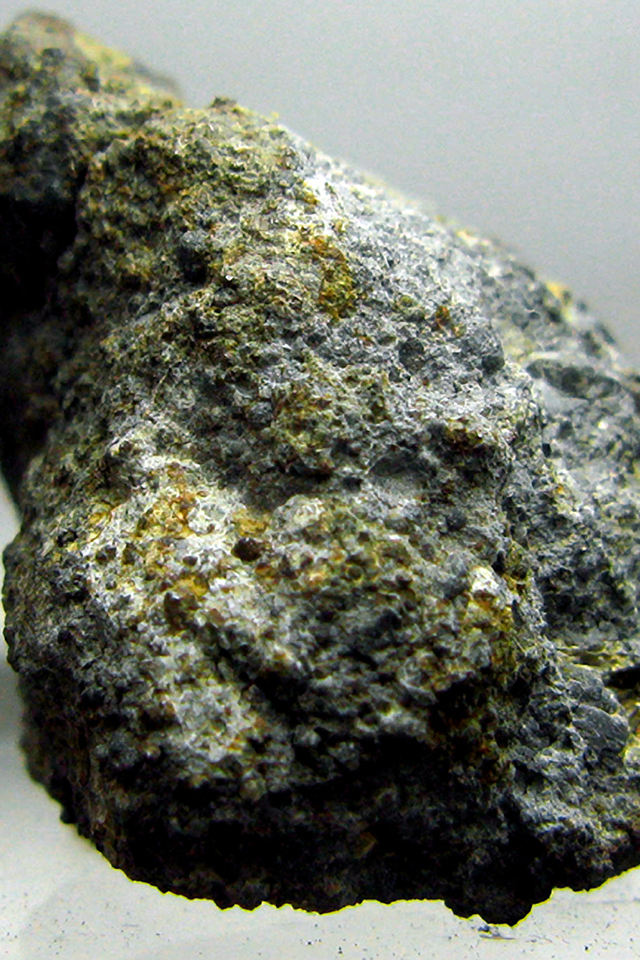

A March 1808 update of Silliman’s report included one of the first chemical analyses of a meteorite. Silliman estimated the original meteorite to have been at least three hundred feet across, traveling 200 to 300 mph when it struck Earth. The object was “everywhere covered with a thin black crust, destitute of splendor,” he wrote, adding, “The surface…feels harsh…produced probably by the intense heat…[and] the stone is thickly interspersed with black globular masses…the largest the size of a pigeon shot.”

That “pigeon shot,” which Silliman encountered when he broke open the stones, came to be called chondrules, a defining characteristic of a meteorite and not found in terrestrial rock. Silliman found nickel alloyed with iron, now known to be common in meteorites, as well as silex (silica or flint), magnesium, and sulfur.

The Weston fall was one of the few to be so geographically concentrated and widely witnessed, and the relative speed with which Silliman arrived on the scene meant he obtained the most accurate and comprehensive account extant of a meteorite strike. The event itself was exceedingly rare; most meteorites burn up on entry, as evidenced by the tally of only 154 meteorites that are known to have landed in the United States since 1807.

Thomas Jefferson was midway through his second term as president when the Weston meteorite fell. He’d hardly won a mandate in 1804; for him to return to the White House, the House of Representatives had to break a tie in the Electoral College between him and opponent Charles Pinckney of South Carolina. Connecticut voters largely opposed Jefferson, a southerner pious New Englanders viewed as an apostate because he worked on the Sabbath and rarely attended church. In addition, Jefferson advocated on behalf of centralized federal control of foreign policy, an anathema to many in Connecticut, where Yale’s President Dwight regularly railed at Jefferson’s foreign policy as a threat to the college’s solvency.

Two weeks after the Weston fall the indefatigably curious Jefferson wrote to a friend who had a sample of the object. “It may be difficult to explain how the stone you possess came into the position in which it was found,” Jefferson wrote. “But is it easier to explain how it got into the clouds from whence it is supposed to have fallen? The actual fact however [sic] is the thing to be established.”

Though he preferred botany to geology, which he dismissed as “too idle to be worth an hour of any man’s life,” Jefferson’s obsession with fossils earned him the disparaging sobriquet, “Mr. Mammoth.”

“We certainly are not to deny whatever we cannot account for,” Jefferson said regarding the Weston event. However, his approach to the event diminished Yale and Silliman. Instead of relying on Yale’s findings, Jefferson appointed astronomer Nathaniel Bowditch to learn everything he could about the stones that fell from heaven. Bowditch’s inquiry confirmed Silliman’s findings.

Silliman’s report, co-authored with Kingsley, ran in the Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences under the title

AN ACCOUNT OF THE METEOR,

Which burst over Weston in

Connecticut, in December 1807,

and of the falling of Stones on

that occasion.

BY PROFESSORS SILLIMAN

AND KINGSLEY.

WITH A CHEMICAL ANALYSIS

OF THE STONES,

BY PROFESSOR SILLIMAN.

The paper was republished by the American Philosophical Society and was read aloud at The Philosophical Society in London and the

Academy of Sciences in Paris—the world’s most prestigious forums, implicitly validating Silliman’s report not only for quality but significance. In 1818, Silliman founded the American Journal of Science, now ranked as the oldest continuously published scientific journal in the United States.

In a 50-year career at Yale, he educated many young scientists, earning the sobriquet of father of science education in America. He married Harriett Trumbull, daughter of Connecticut’s governor; they had four children. He married Sarah Isabella Webb after Harriett’s death and died at 85 in 1864. A college at Yale bears his name and his portrait hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington.

Scientists now believe that the Weston meteorite probably began its long journey 30 million years ago with a collision involving asteroids. Gravity pulled one hunk to Earth in 1807. That meteorite is classified as an H4 chondrite—H meaning “high in iron”—and was the first meteorite collected by Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History when that facility opened in 1866.

Only 50 lb. of the 1807 meteorite’s estimated 350 lb. mass can be accounted for. Some pieces likely collected dust on Weston mantelpieces until being thrown out; others may lie where they buried themselves that chilly morning long ago. Of the fragments of sky stone that Silliman collected, some saw use in his analysis; others went to fellow scientists and other institutions in exchange for samples from other meteorites.

The remaining Weston Fall sample is the fragment that Colonel Gibbs purchased soon after the event. Yale bought that space souvenir in 1825, along with the other contents of the Gibbs mineral collection. The Weston piece, roughly the shape of Australia, is on display at the Peabody Museum in New Haven, Connecticut.