Early on a Hawaiian morning more than seven decades ago, three young soldiers stepped off a bus at a stop halfway between Pearl Harbor and downtown Honolulu. The three, all members of the California National Guard’s 251st Coast Artillery Regiment, then walked down a residential street to the front gate of John Rodgers Airport.

Despite the early hour—barely 7:15 a.m.—the field was busy. A Hawaiian Airlines DC-3 was being prepped for a flight to Maui, and an Aeronca 65TC Tandem carrying a local lawyer and his teenage son had already taken off on a sightseeing flight. As the soldiers walked toward two Piper Cubs parked in front of the K-T Flying Service hangar, three small aircraft belonging to other operators were already jockeying for position on the airfield’s 1,000-foot-long takeoff strip, their student pilots and instructors hoping to get airborne before the morning winds kicked up along Oahu’s south coast. One after another the airplanes lifted into the sky, then turned in different directions, setting out on the first training flights of the day.

After watching the trainers depart, the soldiers prepared for their own takeoff. Two of the men—20-year-old Sergeant Henry C. Blackwell and 21-year-old Corporal Clyde C. Brown—were licensed pilots who’d been taught to fly during their off-duty hours by Robert Tyce, K-T’s co-owner. The GIs had arranged to rent the Cubs in order to take two nonflying fellow soldiers on an early-morning sightseeing trip, though only one friend—21-year-old Sergeant Warren D. Rasmussen—had sacrificed his Sunday morning sack time to see Oahu from the air.

As the soldiers strapped themselves into the bright yellow Cubs—two in one aircraft and the third in the other—38-year-old Bob Tyce and his 31-year-old wife, Edna, were leaving their Honolulu home for the airport. While Sunday was a normal workday for the couple, they also wanted to be on hand when Blackwell and Brown returned. The two Guardsmen were scheduled to leave for the mainland the next day, and Bob and Edna, who thought of the young men almost as family, wanted to say their farewells.

What neither the Tyces nor the three soldiers knew was that disaster was about to descend on them. The date was December 7, 1941; in less than an hour the GIs would become the first American military personnel killed during the Japanese attack on Oahu, and Bob Tyce would be the assault’s first civilian victim. Though their deaths quickly became mere footnotes to the larger story of Pearl Harbor and America’s subsequent entry into World War II, they also sparked a continuing historical controversy and ultimately led one investigator to revisit a case that had been closed for decades.

Blackwell, Brown and Rasmussen were in the air that morning by virtue of a contract won in November 1939 by Tyce and his partner in K-T, Charles B. Knox. Their small company joined the government’s Civilian Flight Training Program, conceived in 1938 by the Civil Aeronautics Authority as a way to boost the nation’s commercial aviation industry by teaching large numbers of college-age Americans to fly.

But as war clouds gathered over Europe, the CFTP also became a way for the United States to create a pool of trained pilots who could quickly transition to military aviation. Colleges and universities offered the necessary ground instruction, while flying schools provided the required 35 to 50 hours of flight time. Tyce and Knox weren’t the only ones in Hawaii to participate in the CFTP; their friendly competitor and neighbor at John Rodgers Airport, Olen Andrew and his Andrew Flying Service, also jumped on the bandwagon, as did 27-year-old Marguerite Gambo, a former student of Tyce’s who’d opened her own small company in a hangar next to K-T’s. All three firms began CFTP training early in 1940.

College students were the program’s intended resource pool, but civilian defense workers and enlisted military personnel soon gravitated to the CFTP to improve their chances of gaining military aviator wings. This was especially true on Oahu, where civilian workers at Pearl Harbor vied with sailors and soldiers for the CFTP slots. After attending ground school at the University of Hawaii, the prospective aviators were assigned to one of the three flying services at John Rodgers for flight instruction.

Among the servicemen who applied for the CFTP were Clyde Brown and Henry Blackwell. Both had grown up in California and joined the same Guard unit—Battery F, 251st Coast Artillery Regiment. When the regiment deployed to Hawaii in late 1940, Brown and Blackwell realized the CFTP would allow them to take the flying lessons they couldn’t afford in California. They entered the program in the spring of 1941, were taught to fly by Tyce and received their licenses that October.

The two Guardsmen were fortunate to be taught by Tyce himself. The CFTP contracts quickly became K-T’s primary revenue generator, and Tyce had to hire several additional instructors to operate a fleet that had grown to 10 aircraft. One of the new hires was 26-year-old Guy Nathan “Tommy” Tomberlin, whom Tyce had taught to fly in 1938. Recently discharged from the Navy, the young pilot instructed part-time for both K-T and the Honolulu Chamber of Commerce–sponsored Hui Lele Flying Club. Tomberlin and Cornelia Fort, a 22-year-old pilot from Nashville hired in September 1941 by Olen Andrew, would later find themselves inadvertently playing starring roles in the dramatic events that played out in the skies over Oahu.

On the morning of December 7, Brown and Blackwell taxied toward the southwest end of the John Rodgers field takeoff strip at about 7:40. Brown was piloting a J3C-50 Cub (NC-26950) and Blackwell a slightly more powerful J3C-65 (NC-35111). It’s not clear in which aircraft Rasmussen was riding, but it’s logical to assume the 6-foot-1-inch, 150-pound soldier would have been in the rear seat of Blackwell’s Cub. The Cubs took off to the northeast, then flew parallel to Waikiki Beach toward Diamond Head before reversing direction and heading west. They were about two miles offshore at an altitude of between 500 and 800 feet, headed toward Camp Malakole, the 251st C.A. Regiment’s base just north of Barber’s Point, on Oahu’s southwest coast.

Some 30 miles to the north, Tommy Tomberlin and his Hui Lele Club student, James Duncan, had just rounded Kahuku Point, Oahu’s most northerly headland. They were flying just onshore in a bright orange Aeronca 65TC (NC-33838) that the club rented from Marguerite Gambo, and were headed southwest at about 1,000 feet toward Laie. Gambo herself was southwest of Kaneohe Bay as her student polished his cross-country skills. Back over Honolulu, attorney Roy Vitousek and his 17-year-old son, Martin, had returned from their sightseeing trip and were circling Rodgers at about 800 feet in their rented Gambo Flying Service Aeronca (NC-33768). And, finally, an Interstate S-1A Cadet (most probably NC-37345) bearing Cornelia Fort and her student, a defense worker named Soumala, was about to turn into the airport’s landing pattern for the last of several touch-and-goes Fort wanted her student to perform before he soloed.

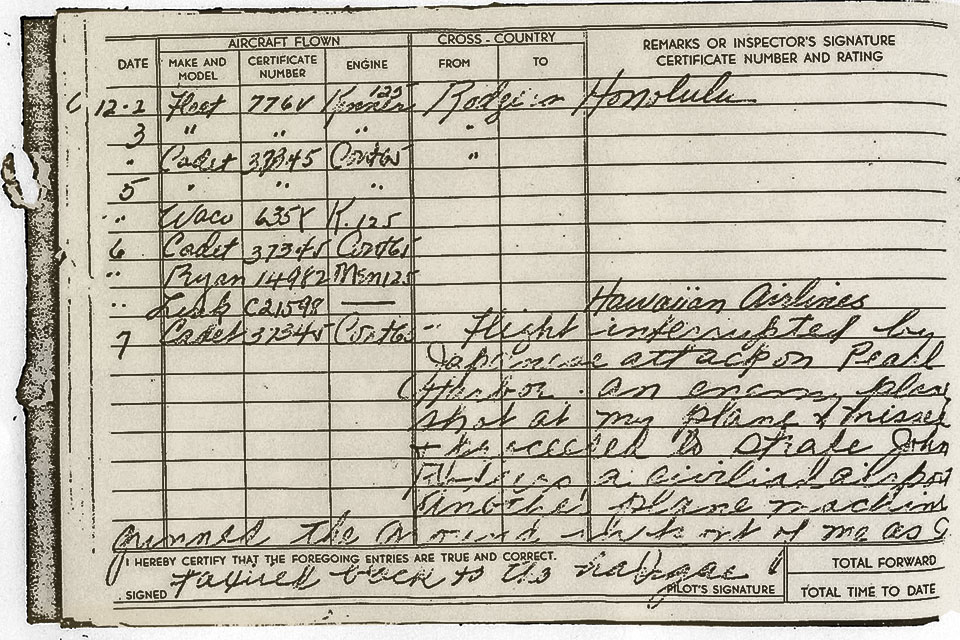

Tomberlin was the first of the civilian pilots to realize that war had come to Hawaii. At 7:52 (as he noted in his logbook), he and Duncan were just north of the Mormon Temple in Laie when two streams of red tracers converged on their Aeronca from behind, punching fist-sized holes in the fabric covering the rear fuselage and vertical stabilizer and shearing two longerons. Tomberlin, in the rear seat, instinctively took the controls and snapped the Aeronca into a descending left bank, toward the sea, jinking as the plane lost altitude. Over the next three minutes two Japanese aircraft—most likely Mitsubishi A6M2 Zeros from an 11-plane flight tasked with strafing Kaneohe Naval Air Station—fired at the Aeronca, though they scored no additional hits. Knowing they had more important targets, the Japanese raced off to rejoin their formation. Tomberlin, keeping the Aeronca just above the waves, headed southeast, intending to sneak through the Pali Pass through the Ko’olau Range on the way back to John Rodgers.

Already approaching the Pali from the southeast were Gambo and her student. As the Japanese fighters pulled up after their first strafing run on Kaneohe, the Aeronca was buffeted with turbulence caused by their passing. Though Gambo initially thought they were Army aircraft, a quick glance at the smoke plumes rising over Kaneohe convinced her they were enemy planes. The interlopers roared past without firing a shot, and Gambo turned toward the Pali and raced for the airport.

At that moment John Rodgers was not quite the haven Tomberlin and Gambo were hoping for. Japanese aircraft had begun attacking Hickam Field, just to the northwest of the civilian airport, at 7:55, and the sky around John Rodgers was filled with Zeros, Aichi D3A1 dive bombers and Nakajima B5N2 horizontal bombers either starting their attack runs or pulling off their targets. Approaching the civilian field at about 800 feet and concentrating on lining up for landing, Roy Vitousek was oblivious to the hostile aircraft below and just north of the Aeronca until Martin called out, “Look! P-40s!” Roy snapped his head to the left and, seeing the huge red ball on the side of one nearby airplane, shouted back: “P-40s hell! They’re Japanese!” The elder Vitousek pulled the Tandem into a steep climb and turned south, out to sea. The rear gunners in two of the passing attack aircraft fired at the Aeronca but did no damage, and Vitousek circled offshore until he saw a chance to slip into John Rodgers. Once on the ground, he and his son ran to their car and raced toward the city.

At roughly the same time the Vitouseks became aware of the Japanese planes, Cornelia Fort and her student were approaching the airfield from the southeast at around 200 feet, about to turn onto the base leg of the traffic pattern. Fort looked to her left, out to sea, to ensure the Cadet was clear to make the turn and saw a military plane heading toward shore at a higher altitude. Noting that it would clear the Cadet by several hundred feet, Fort leaned forward to tell her student to begin the turn—and saw a different military plane headed directly at the Cadet on a collision course.

Fort grabbed the controls and pulled up, jamming the throttle open. Annoyed at what she assumed was a hot-dogging Army pilot, she glanced down as the interloper passed beneath the Cadet, hoping to get its registration number. Instead she saw the red balls on the plane’s wings and, looking toward Pearl Harbor, saw smoke billowing into the sky. Realizing, as she later wrote, that “the air was not the place for our little baby airplane,” Fort put the Cadet on the ground as quickly as she could and taxied to the Andrew Flying Service hangar, bullets from a strafing plane kicking up dust in front of her. She and her student jumped from the aircraft and sprinted to Andrew’s office, where Fort’s “The Japs are attacking!” exclamation was met with disbelieving laughter. The laughing stopped abruptly, however, when a mechanic ran in from outside and shouted, “That strafing plane that just flew over killed Bob Tyce!”

The co-owner of K-T Flying Service and his wife had arrived at their hangar at about 7:50, and soon after that Bob walked out on the ramp to stand in the sun. Almost immediately he turned and shouted for Edna, who was in the office, to join him. As she walked out, Bob pointed to pillars of smoke boiling into the sky to the west and said, “I think Hickam Field is having some kind of an accident.” The couple could hear the thump of explosions, and wondered if there had been a fire at the base’s ammunition dump.

While Bob and Edna stood staring at the smoke, they noticed an airplane approaching from the direction of Hickam, flying low and fast. As the plane sped toward them, Edna said, “They’re flying too low over a civilian airport.” She looked at her watch—noting the time as exactly 7:55—when the mysterious aircraft roared past, so low that Edna clearly saw the two crew members.

The plane zoomed out over the ocean, turned steeply and came back toward the K-T hangar. As the Japanese pilot opened fire, just missing Cornelia Fort’s taxiing Cadet, Bob turned to say something to Edna and a bullet hit him in the back of the head, exiting through the side of his throat and leaving a hole that Edna later described as being big enough to “put a golf ball through.” He dropped to the ground, and his wife—unhurt despite the fact she’d been standing right next to him—reacted as the nurse she had once been, checking Bob’s pulse, though she knew intuitively that he was already gone.

The aircraft that killed Tyce was likely the same one that soon afterward strafed the Hawaiian Airlines DC-3 that had been preparing for its morning departure to Maui. The airliner was hit by dozens of rounds that damaged its left wing, cockpit, both engines and passenger compartment. Fortunately, passengers and crew were unhurt; they’d been hustled off the plane when the ground staff realized Hickam was under attack.

Though Japanese planes made several passes over John Rodgers, it initially appeared to the shaken survivors of the strafing that Tyce was the airfield’s only casualty. Then, nearly an hour after the attack, Edna realized that the two Cubs rented by the young California soldiers had not yet returned.

The best witness we have for what happened to the Piper Cubs bearing Brown, Blackwell and Rasmussen is Navy Machinists’ Mate 1st Class Norman B. Rapue, a 41-year-old sailor assigned to YT-153, a 65-foot motor tugboat commanded by Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Ralph Holzhaus. Rapue’s account of the events of December 7 appeared both in Honolulu’s Star-Bulletin newspaper on December 20, 1941, and as part of a sworn deposition he gave on February 3, 1942.

At 7:55 a.m. YT-153 was underway for the Pearl Harbor entrance channel to transfer a harbor pilot to the incoming cargo vessel USS Antares. The tug was about 400 yards south of channel buoy 4 when the crew saw explosions engulfing Hickam, barely a mile off their port side. Rapue saw the bright yellow Cubs ahead of the tug, offshore and south of Fort Weaver—a coast artillery post on the west bank of the entrance channel—as the planes were attacked.

“They didn’t have a chance,” Rapue told the Star-Bulletin. “Both were cruising about two and a half miles offshore at about 500 feet altitude when seven Japanese planes swooped down….One of the yellow [civilian] planes plummeted straight down into the ocean while the other circled for a moment and then plunged down.” Rapue modified his account only slightly in the 1942 deposition, saying that the Cubs were about two miles south of Fort Weaver, that they were attacked by “a number” of Japanese planes and adding that the second yellow trainer “floated for a while” before sinking. Though an Army crash-rescue boat sortied from Pearl Harbor within 30 minutes of the incident, its crew found no trace of the Cubs or their occupants.

By the evening of December 7, Edna Tyce assumed the two rented aircraft and the young soldiers—she believed there were four, based on what Brown and Blackwell had said when filling out the rental forms the day before—were victims of the Japanese attack. But the young widow had to wait 11 days for any sort of physical confirmation: On the morning of December 18, Dr. Dai Yen Chang, a prominent Honolulu dentist, was walking on the beach just west of the entrance to Pearl Harbor when he found a large piece of bright yellow doped fabric and what appeared to be a section of an airplane’s outer wing panel. Both Edna and a Civil Aeronautics Authority inspector positively identified the wreckage as having come from one of the K-T Cubs.

The downing of the two aircraft and the deaths of the Guard soldiers quickly became mere historical footnotes as America rushed headlong into World War II. Brown, Blackwell and Rasmussen were officially listed as “Missing in Action—Body Not Recovered,” and over time their families moved on with their lives. In October 1942, Edna Tyce married Robert Q. Palmer, a sailor based at Pearl Harbor, and in 1943 she and Charlie Knox received a check for $2,335.56 from the government’s War Damage Corporation as full settlement of their claim for the loss of the two Cubs. In 1944 K-T Flying Service was sold to new owners, who liquidated the company within a few years and sold the hangar to an air taxi service. Charlie Knox saw military service in WWII and died in Nevada in 1949. The Palmers eventually settled in northern California, where Edna died on July 20, 2000, at age 89. With her death, the story of the shot-down Piper Cubs and the three young soldiers they carried—the first American military personnel killed by the Japanese in WWII—seemed definitively at an end.

But then in 2008 a retired U.S. Marine began writing a new chapter in the story based on a discovery made just weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack.

On the afternoon of December 31, 1941, soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 35th Infantry Regiment, on a work detail at Fort Kamehameha—a post south of Hickam Field and bordering the west end of John Rodgers Airport—made a macabre discovery. Washed up on the beach was a brown Army service shoe containing a badly decomposed human foot encased in a waterlogged Army-issue sock. In that age before DNA testing, there was no way to determine to whom the foot belonged, and on January 2, 1942, it was marked “Unknown” and buried in Schofield Barracks’ post cemetery. In the early 1950s it was re-interred in grave A-780 at Oahu’s National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

And the foot would have remained at Punchbowl, unidentified, had it not been for Ted Darcy. A retired Marine, Darcy runs the Massachusetts-based WFI Research Group, founded in 1984 to compile and preserve records pertaining to the U.S. armed forces in WWII. WFI used primary-source documents from all the military services to build extensive databases, one of which lists personnel killed in the conflict, and another those still classified as missing in action. The latter proved especially valuable when, in December 2010, a cousin of Henry Blackwell’s contacted WFI seeking further information.

Darcy cross-referenced his databases and pulled additional facts from such official records as the Individual Deceased Personnel Files the Army had compiled during and after the war on Blackwell, Brown and Rasmussen. The key record was one produced by the Army’s Hawaiian Department headquarters at Fort Shafter in the months following the Pearl Harbor attack. The document lists more than 240 Army personnel killed in the assault who had not been immediately identifiable, either because the remains were badly charred or consisted only of “disarticulated” body parts. While investigators ultimately identified most of the men on the list—through fingerprint records, dental charts, tattoos or even laundry tags on what was left of their uniforms—the owner of the foot recovered by the 35th Infantry Regiment soldiers and tagged as “Unknown Case Number 238” remained a mystery.

That entry did offer one important detail: The Army shoe in which the foot was encased was a size 11. By checking the three Guard soldiers’ deceased personnel files, Darcy determined that Henry Blackwell had worn size 11D shoes. While it would be impossible to positively identify the foot should it be exhumed (like the majority of decomposed remains interred in the weeks after Pearl Harbor, it had been sprayed with chemicals that would compromise the validity of a modern DNA test), Darcy ultimately concluded that the foot was, in fact, Blackwell’s.

In 2011 Darcy submitted evidence supporting the identification of the Case 238 unknown to the Department of Defense’s Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, the Hawaii-based agency tasked with locating, recovering and identifying the more than 83,000 Americans still missing from the nation’s conflicts. He has heard nothing from JPAC since that time, and my own recent request to the agency for an update on the Blackwell case elicited a form response that “JPAC does not discuss the specific progress of an unresolved case out of respect for the families’ privacy.” It seems that final closure for Henry Blackwell’s surviving family members will have to wait a while longer.

Stephen Harding is the author of eight books and some 300 articles. His most recent book is The Last Battle: When U.S. and German Soldiers Joined Forces in the Waning Hours of World War II in Europe. Additional reading: Long Day’s Journey Into War, by Stanley Weintraub, and At Dawn We Slept, by Gordon W. Prange.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2014 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!