As Americans mark the centennial of the National Park Service, many still refer to environmentalist John Muir (1838–1914) as the “Father of the National Parks.” Indeed, among other accomplishments he successfully lobbied Congress to pass the 1890 bill that established Yosemite National Park.

But years before Yosemite came Yellowstone, which in March 1872 officially became the first national park in the world, let alone the country. Yellowstone’s first superintendent, Nathaniel Langford, had no salary, no funding, and could do little to protect the park. In 1878 Congress provided his successor, Philetus Norris, with minimal funding to improve operations. Poaching and vandalism remained a problem, however, so in 1880 U.S. Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz hired Harry Yount as park gamekeeper.

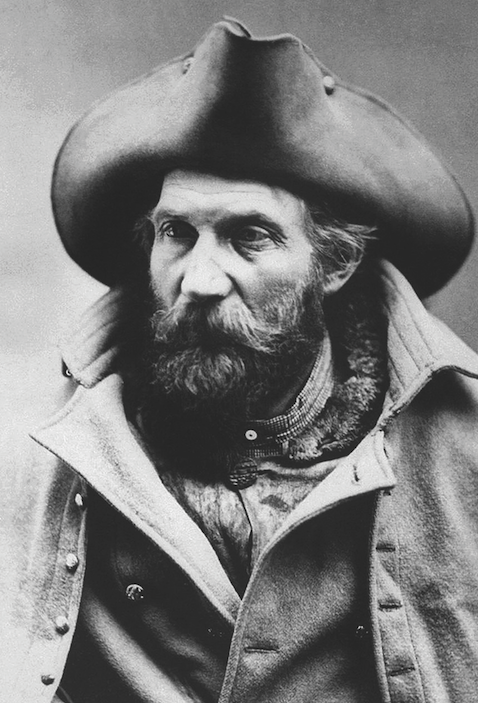

While Yount served just 14 months and certainly never became a household name like Muir, his efforts at Yellowstone helped inspire the creation of the National Park Service on Aug. 25, 1916. In his 1928 book “Oh, Ranger!” Horace Albright, who a year later became the second NPS director, recognized “Rocky Mountain Harry” as the “father of the ranger service, as well as the first national park ranger.”

Harry Yount, born Henry S. Yount in 1839, grew up in Missouri’s Harmony Township, about 90 miles southwest of St. Louis. His uncle George C. Yount left Missouri for Santa Fe and became a notable free trapper and explorer in the Southwest and California (see “Pioneers and Settlers” in the February 2016 Wild West).

CIVIL WAR SOLDIER

Harry Yount enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War and rose to the rank of company quartermaster sergeant. After his July 1865 discharge in Little Rock, Ark., Yount was hired on at Fort Kearny, Neb., as an Army bullwhacker. In July 1866 his first bull train reached Fort Laramie (in what would become Wyoming) and soon continued on the Bozeman Trail bound for newly established Fort C.F. Smith in Montana Territory.

Near the Bighorn River, Sioux warriors harassed the teamsters for several days. After Harry shot at one charging warrior, killing the man’s horse, the Sioux bothered them no more. He continued as a teamster along the Bozeman Trail and in 1868 did a stint at Wyoming Station, delivering finished ties and cordwood to Union Pacific crews.

He also worked for several years as a scout, trapper and hunter, during which time he became acquainted with Lakota Chiefs Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, Shoshone Chief Washakie and Northern Cheyenne Chief Dull Knife (aka Morning Star).

Starting in 1872, Yount spent seven summers as a packer and guide for the Hayden Geological Survey in what would become the states of New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming and Utah. (After exploring Yellowstone in 1871, Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden had been a leading proponent of the national park.)

Late in the 1874 season the survey party encountered deep snow in northwest Colorado. Some of the men, having lost their compass, became disoriented and delirious, and Yount told pack train leader Chunky Johnson to strap anyone who attempted to wander off to his mule. Yount then guided the party to a ranch on the Yampa River, where the men rested before continuing on to the railhead in Rawlins, Wyoming Territory. Perhaps it was during this trip Yount earned the nickname “Rocky Mountain Harry.”

After sundown on Aug. 25, 1878, Bannocks raiding through Yellowstone fired on Yount’s Henry Lake camp, prompting the guide, topographer Allen Wilson and others to flee into the woods. Nobody was hurt, but the Bannocks made off with their mounts and food supplies. It took Yount’s party three days to reach expedition headquarters in the Upper Geyser Basin.

That same summer as Yount guided survey member James Eccles’ attempt to summit Grand Teton, Harry slipped on a glacier and slid down the ice toward a large crevasse. His buckskin pants gripped the ice, stopping his fall, but according to Wilson, Yount was clinging to the icy rock like “a starfish hanging to a breakwater” before Wilson threw him a lifeline. The party turned around just shy of the summit, though the views were spectacular.

In winter Yount often hunted and trapped the Laramie Mountains, and in the early 1870s he collected study specimens of Rocky Mountain species —including mountain lions, foxes, wolves and sage grouse—for the Smithsonian Institution. In pursuit of grizzly bear specimens, he sometimes crawled right into their dens.

While always prepared with powder and ball for a second shot, he once had to hurriedly reload a third time in the dark to shoot one determined bear. As grizzlies often weighed more than 800 pounds, he used a mule team to drag their carcasses from the dens. Yount kept after grizzlies, usually employing a .40-90 Sharps, until his mid-60s. In 1892 he brought five grizzly skins into Cheyenne, Wyo., where he expected to get a $250 bounty on each hide.

DEFENDER OF WILDLIFE

Yount was mostly a defender of wildlife after reporting for duty as Yellowstone gamekeeper in July 1880. He built a cabin at the juncture of the Lamar and Soda Butte valleys so as to protect wintering bison and elk. In reports to Superintendent Norris and Secretary Schurz, though, he stressed his inability to safeguard the entire park and called for “a small, active, reliable police force, to receive regular pay during the spring and summer at least, when animals are likely to be slaughtered by tourists and mountaineers.

It is evident that such a force could, in addition to the protection of the game, assist the superintendent of the park in enforcing the laws, rules and regulations for protection of guideboards and bridges, and the preservation of the countless and widely scattered geyser cones and other matchless wonders of the park.”

After resigning his Yellowstone post in September 1881, Yount homesteaded and prospected in Wyoming. In 1892 he helped develop a marble quarry near Wheatland but sold his interest long before the quarry became profitable. In 1898 he homesteaded along Halleck Creek in Albany County and brought watermelons, corn and other vegetables to market in Cheyenne. By 1912 he had sold his place there and settled in Wheatland, where he remained until his death from heart failure on May 16, 1924.

The 1916 creation of the National Park Service was largely the result of a campaign spearheaded by businessmen and conservationists Stephen Mather and J. Horace McFarland and journalist Robert Sterling Yard, and Mather was appointed first director of the NPS.

But as “first ranger” at Yellowstone 35 years earlier, Harry Yount had done his part by setting standards and exemplifying the spirit of the future service. Hayden had recognized his efforts by naming Younts Peak, a summit in the Absarokas southeast of Yellowstone, after Harry, and in 1994 the NPS established the Harry Yount Award for rangers who demonstrate excellence in their duties.