The Civil War has long been recognized as a conflict that ushered in many military and technological innovations—from trench warfare and repeating firearms to submarines and ironclad warships—that foreshadowed the evolution of warfare in the 20th century. What may be less well known, but no less important, is that the war also witnessed the service of the very first female chaplain in the U.S. military, Ellen Elvira Gibson Hobart. A rather obscure correspondence file that found its way into the letter files of the Volunteer Service Division in the Adjutant General’s Office at the War Department documents the little-known story of how “Ella” Gibson Hobart faithfully served the 1st Wisconsin Heavy Artillery during the Civil War but tried unsuccessfully to obtain War Department recognition for her efforts.

Ellen Gibson was born May 8, 1821, in Winchendon, Mass., to Isaac and Nancy (Kimball) Gibson. In 1827, Isaac moved the family back to his hometown of Rindge, N.H., where Ella became a successful teacher in the local public schools. She also taught children at Winchendon, Ashby, and Fitchbury, Mass. In 1852 Gibson embarked on a career as a writer and public lecturer on abolition, women’s rights, and other moral reform issues. According to later tributes, she achieved early attention as “one of the very first women in America who spoke from the public rostrum,” and did not shy away from challenging “the creeds of the church and antiquated political and religious dogmas.” After the Civil War began, Gibson engaged in organizing Ladies’ Aid societies in Wisconsin to support the needs of soldiers in the field, and was involved with the Northwest Sanitary Fair in Chicago.

On July 21, 1861, Gibson married John E. Hobart, in Geneva, Ill. (they later divorced on August 5, 1868). An ordained Methodist clergyman who entered the Spiritualist tradition in 1856-57, John Hobart soon became chaplain of the 8th Wisconsin Infantry. By then an ardent patriot and Abolitionist, Ella followed her husband to camp and assisted with the spiritual well-being of the troops as well as the physical comfort of the sick and wounded. She became ordained herself in the Spiritualist tradition by the Religio Philosophical Society of St. Charles, Illinois, on November 13, 1863. Her ordination license, or Certificate of Fellowship—a copy of which was included in her correspondence file at the AGO—recognized Hobart as a Regular Ordained Minister of the Gospel and authorized her “to solemnize marriages in accordance with law.” An accompanying statement from the board of the Religio Philosophical Society, dated May 2, 1864, confirmed Hobart’s status as an ordained member and recommended her for “the appointment to a Chaplaincy either in the Regular Army of the United States or for a post in Regimental Volunteer Service Chaplaincy.”

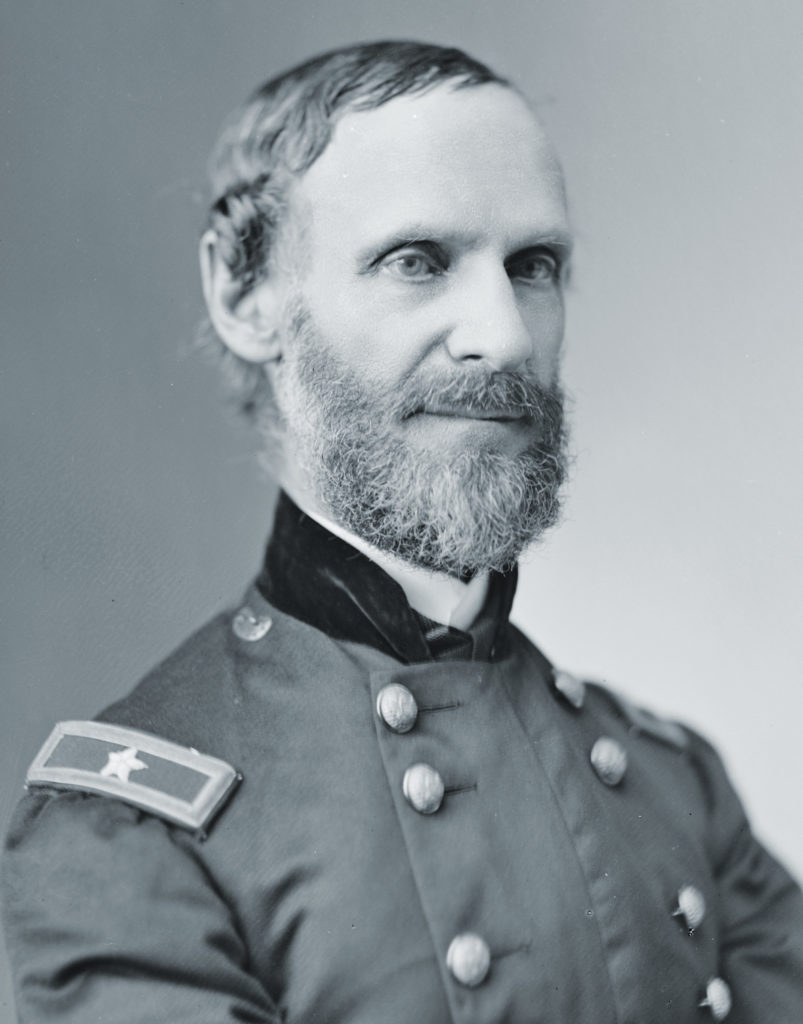

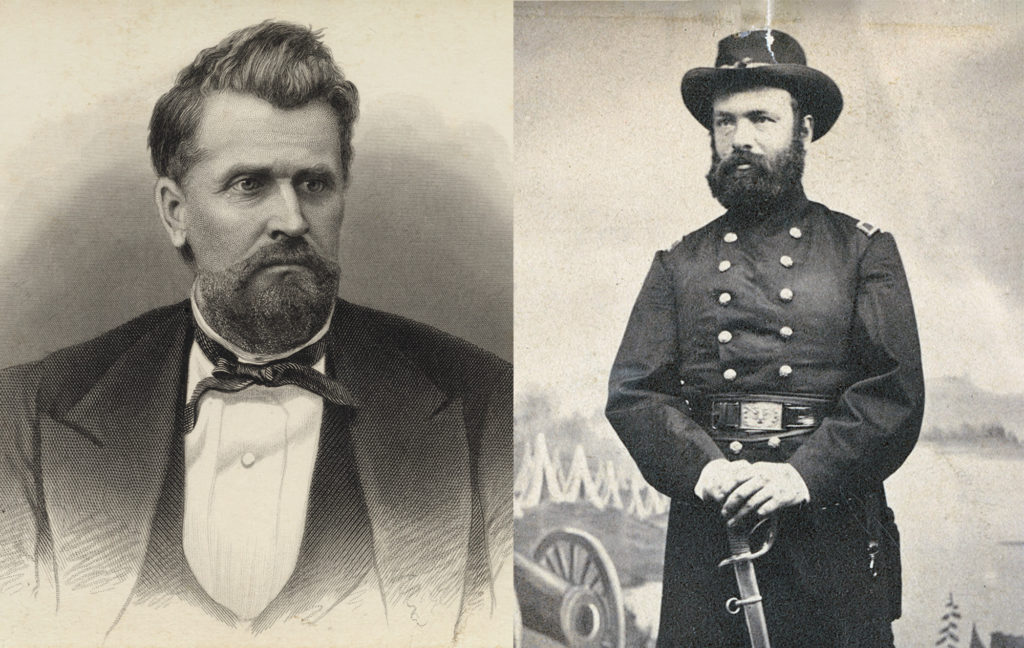

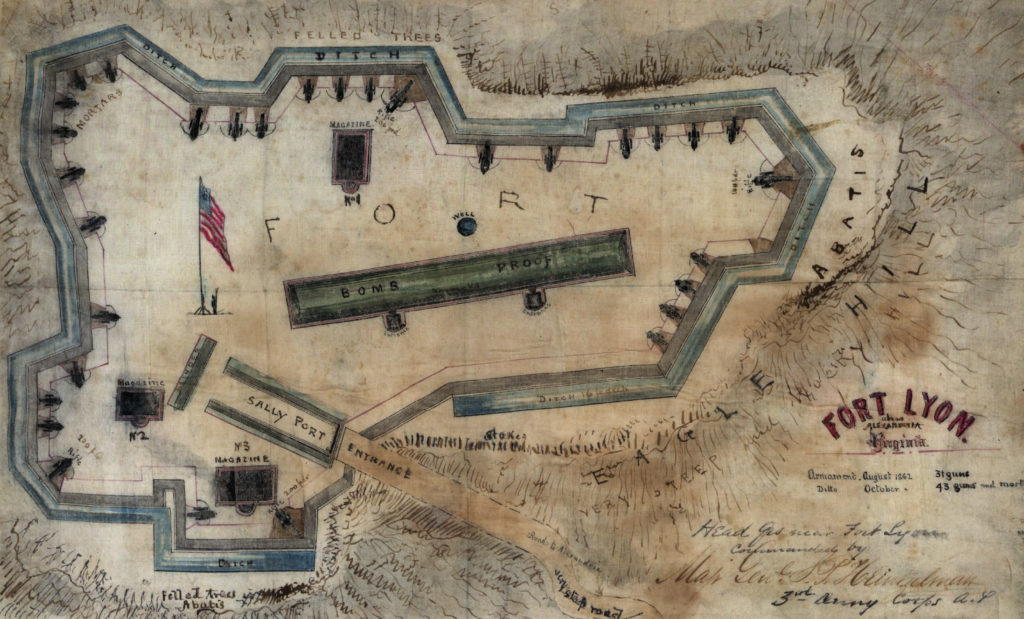

An opportunity for regimental service soon came along as Ella began to perform unofficial duties as chaplain of the 1st Wisconsin Heavy Artillery while batteries E through M were being organized at Camp Randall in Madison, Wis., in September 1864. The regiment then moved to the defenses outside Washington, D.C., and at Fort Lyon in Alexandria, Va., Hobart was elected chaplain by the regimental officers on November 22, 1864. Wisconsin’s adjutant general wrote to the War Department on December 17, 1864, requesting confirmation of Hobart’s election by securing her an official appointment to the regiment’s chaplaincy. Despite having a roundabout endorsement from President Abraham Lincoln, to whom Ella had previously applied for support and who expressed no objection to her commission (even though Lincoln claimed to have no legal authority to approve such an appointment), Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton flatly denied the request on the grounds that no precedent existed to muster a female into military service. In spite of the official rejection, Ella Hobart continued to minister “faithfully and to the satisfaction of the officers and enlisted men” of the 1st Wisconsin for the remainder of the war until July 12, 1865.

Official recognition for Hobart’s military service as a chaplain came slowly in the postwar years. On March 3, 1869, a joint resolution was finally introduced in Congress to grant Hobart full pay and related emoluments “for the time during which she faithfully performed the service of a chaplain…as if she had been regularly commissioned and mustered into service.”

To support her case for back pay, Hobart penned a lengthy narrative of her military service to Adjutant General Edward D. Townsend, in which she adamantly defended her work as a chaplain despite the inherent disadvantages she faced in her profession because of her gender:

Boston

Dec. 9th 1869.

Maj. Gen. E.D. Townsend

A.A. Gen. U.S.A.

Washington, D.C.

Sir—

Understanding that you demand further proofs to establish my Claim passed by Congress last session, permit me, Sir, to make a plain statement of facts as I know and understand them. Bear with me and I will be as brief as possible.

Last July, I received letters from three of the officers of the Regiment, saying, that they were ready to give again, their affidavits, when called upon. I then saw Col. Swift’s Agent in Boston, who told me, that the proofs already forwarded and then on file, upon which the Bill passed Congress, were sufficient, therefore, I made no farther effort to procure them. I regret, now, exceedingly that they were not then obtained, as their non-appearance seems to have given rise to the supposition that such proofs as to service actually rendered could not be procured.

But, Sir, permit me, torefer you to those on which the Bill passed as evidence, not only of such service, but of nearly two years unpaid toil, previous to my entering the Army as Chaplain.

Have patience, Sir, I beseech you, and give me a hearing. It was in consequence of this two years faithful service, in organizing Soldiers Aid Societies in Wisconsin, raising funds for the Sanitary Commission, and rendering service in other states, in various ways, both North and South that influenced Governor Lewis, General Fairchild—then State Secretary—and Hon. S. D. Hastings—State Treasurer, to recommend this Chaplaincy to the then enlisting Regiments in Camp Randall, Madison, Wisconsin.

Governor Lewis and General Fairchild desired to give me a paying position—the former, saying, that he would commission me provided I was elected by any Wisconsin Regiment, for enquire, then, why he did not do so: Have patience, Sir, and I will give you the facts as I understand them, and as reported to me by him and others.

The Regiment was not organized until after we reached Alexandria. I went down with one of the Batteries. Col. Meservey was already there, and when the election came off he forwarded the appointment to Governor Lewis, who instead of Commissioning me wrote to the Secretary of War enquiring if he would authorize the mustering provided he did commission me. Mr. Stanton replied in the negative. Every effort seems to have been made by the Wisconsin State authorities to induce him to reconsider his decision, but of no avail. Even the approbation of President Lincoln, obtained by myself failed to move him. The Officers of the Regiment were not behind in that endeavor, as their Petition will testify; they affirmed they would not elect any other Chaplain, and I signified my willingness to remain and act as Chaplain as long as they were satisfied, without any expense to them or the Regiment. Secretary Stanton, then advised me to put a Bill in Congress and obtain the place by a special Act, which I then did not feel disposed to do.

Now for the service. I did all and more than was required of me in the Hospital; and as to lecturing on preaching to the men—a portion of the Sundays I held two or three services in various barracks, speaking also week day evenings, and conducting funerals in the open air, as late in the season as December. We had no Chapel or place of meeting except the barracks, and the open air.

It does not seem modest for me, Sir, to Speak of these labors particularly, even could I without appearing egotistical and incurring your contempt. I would therefore, refer you to Colonel Meservey, and Surgeon Waterhouse of the Regiment, General Auger and Capt. Lee, for proofs; in one instance, as to service rendered under the most difficult, sad and soul harrowing circumstances in procuring a furlough for a soldier to escort him to Wisconsin a distracted mother and the dead body of her son, whom she expected on her arrival at our Headquarters to find alive and well, but whose lifeless son had been taken to the Dead House one hour previous. He was her son; She could not leave his body there! She was too distracted to return alone! O, Sir, though you may think lightly of it, a mother is a mother, and appreciates such service—and does not God; and will not my country, and render to a woman, who knew neither ease nor rest for nearly three long years, her pay to keep her from starving!

O, Sir, had I been a man, my ability and usefulness would never have been questioned! The reason I am so explicit is because I understood you question whether such service as is claimed ever was or could ever be rendered.

Now as to the time of service. Colonel Meservey and all his Officers in Camp at that time committed themselves to me on September 30th, 1864. I was not “a favorite” of the Colonel or any of his Officers. I had been speaking there and had in six weeks time given thirty nine lectures in Camp Randall, [illegible word]. I had never seen the Colonel until that day, but he had heard of my labors and the report with the papers, in my possession, influenced him to grant me this position. Neither was I acquainted with the other Officers of the Regiment.

Colonel Meservey left for Alexandria that day, but as I was informed, not till after he had seen Governor Lewis and obtained from him the ratification of his promise made to me, that he would commission me, provided I was elected Chaplain of any regiment.

From that time Sept. 30th 1864, I date my claim for pay, because, from that day I labored particularly for that Regiment or the Batteries composing it, then being filled up in Camp Randall and till I left for Alexandria Oct 17th, and reached there Oct. 22d and until the election Nov 22d, when the Regiment composing these several batteries, could legally elect me, I was doing all in my power for the comfort and happiness of the men the [sic] serve as after the election when I was legally acknowledged Chaplain-elect of the Regiment.

I claim that all this time I was “faithfully performing the services of Chaplain to said Regiment as if I had been regularly commissioned and mustered into the service,” and was bearing my own expenses independent of the Government or any individual, either in the Regiment or out.

Now, Sir, when does my term of service commence—not when I was commissioned, for I never was commissioned, not when I was mustered for I never was mustered; from when I was elected, or when a sufficient number of days after the election had expired to have had my commission arrive from Wisconsin and myself been legally mustered into the service as Chaplain? The mustering might then have taken place in about ten days after the election—Nov. 22d, which would have been December 1st or 2d.

Now, Sir, I claim as the Resolution provides, “shall be entitled to receive the full pay and emoluments of a Chaplain in the United States army for the time during which she faithfully performed the services of a Chaplain to said Regiment,” that that “time” commenced Sept 30th 1864 and continued till July 4th 1865 and also claim three months pay after the close of the war the same as other Chaplains, with all the emoluments of a Chaplain during this time. I am not indebted to the government except the use of a tent a few weeks, I had none of the privileges of an Officer of the rank of Chaplain, but performed the duties of that office, while to all intents and purposes I was only a citizen as far as the government was concerned.

I am not disposed, Sir, to be captious or exacting but humanity, benevolence and patriotism is paid very poorly, if I am entitled to nothing from government or my fellow creatures.

The encouragement to utility, morality, charity and love is meager indeed, when it becomes less in the eyes of this Republic than the value of a bridge or a piece of land. Where will you find your Florence Nightingale in another war if you refuse thus to acknowledge them in this.

O, Sir, I beseech you, stand not in the way of this Claim, for it is due me as you may know if you will take the pains to enquire of Governors Lewis, Fairchild and Salamon and many other gentlemen to whom you may be referred.

I have need of this pay as I am alone, alone in this world—all my loved ones are dead or dying and with my health ruined, like many a male Soldier of the Rebellion I enquire, shall I end my days in a pauper house, disabled, sad and misanthropic realizing that “Republics are indeed ungrateful?”

Sir, I have given you a synopsis of facts as far as my knowledge extends and if you desire farther particulars explanations or references, please, inform me. Do not suffer misrepresentation or prejudice to influence you in a matter which though to yourself of slight importance, nevertheless, involves the real or woe of one whose comfort and happiness are as dear to her, as are yours to you or even as are a President’s or titled Monarch’s to them.

Aware that you are but a servant and can only obey the law under which you are sworn, permit me, Sir, to add, in conclusion, that whatever the Resolution is proven to signify that I will accept as a Resolution though not as my Claim and right from Government, unless it includes all I demand.

Therefore, if it should be proven that the time of service included in the Resolution did not commence till much later than I claim, I shall still maintain that my labors with the Regiment began Sept 30th and also my expenses.

I have recently written to four of the Officers of the Regiment for Affidavits and will forward them as soon as received.

In hopes that justice will finally be rendered me, I await your action and reply.

Mrs. Ella G. Hobart

242 Harrison Avenue

Boston, Mass.

Hobart finally received payment for her services as a chaplain on March 7, 1876, in the amount of $1,210.56. Recognition for her military service, however, remained elusive. The 1869 joint resolution was amended twice in the House of Representatives, in 1880 (H.R. 8578) and 1892 (H.R. 3842), to recognize Hobart as chaplain of the 1st Wisconsin Heavy Artillery and to muster her into the Volunteer Service of the United States at the equivalent grade. Both measures apparently failed. Meanwhile, Hobart (who by then had reverted to using her maiden name of Gibson) continued her career as an author, penning articles for The Truth Seeker, The Boston Investigator, The Ironclad Age, and The Moralist (and serving as editor of the latter periodical in the early 1890s). She became a supporter of the Free Thought movement and a charter member of the National Liberal League. Ellen Hobart died on March 8, 1901, in Barre, Mass.

It was not until 100 years after Hobart’s death that a grateful nation finally recognized her military service when Congress posthumously granted Hobart the grade of captain in the Chaplain Corps of the U.S. Army via the National Defense Authorization Act of 2002. By then, however, Hobart had already been eclipsed for nearly 30 years as the first “official” female chaplain in the military by Lt. Dianna Pohlman Bell, who was commissioned as a U.S. Navy chaplain in 1973.

John P. Deeben holds B.A. and M.A. degrees in American History from Gettysburg College and Penn State University and is a reference archivist with Research Services at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. He has published articles in numerous genealogical journals and magazines, including Prologue, American Ancestors, and National Genealogical Society Quarterly.