William “Buffalo Bill” Cody truly was a frontiersman, scout and Indian fighter. But he became bigger than life as a showman thanks to newspapers, pulp fiction, dime novels, excellent promotion and his crowd-pleasing Wild West extravaganza. By the late 19th century, the name “Buffalo Bill” was recognized all over the United States and Europe. But Cody was not the first man to carry that catchy moniker.

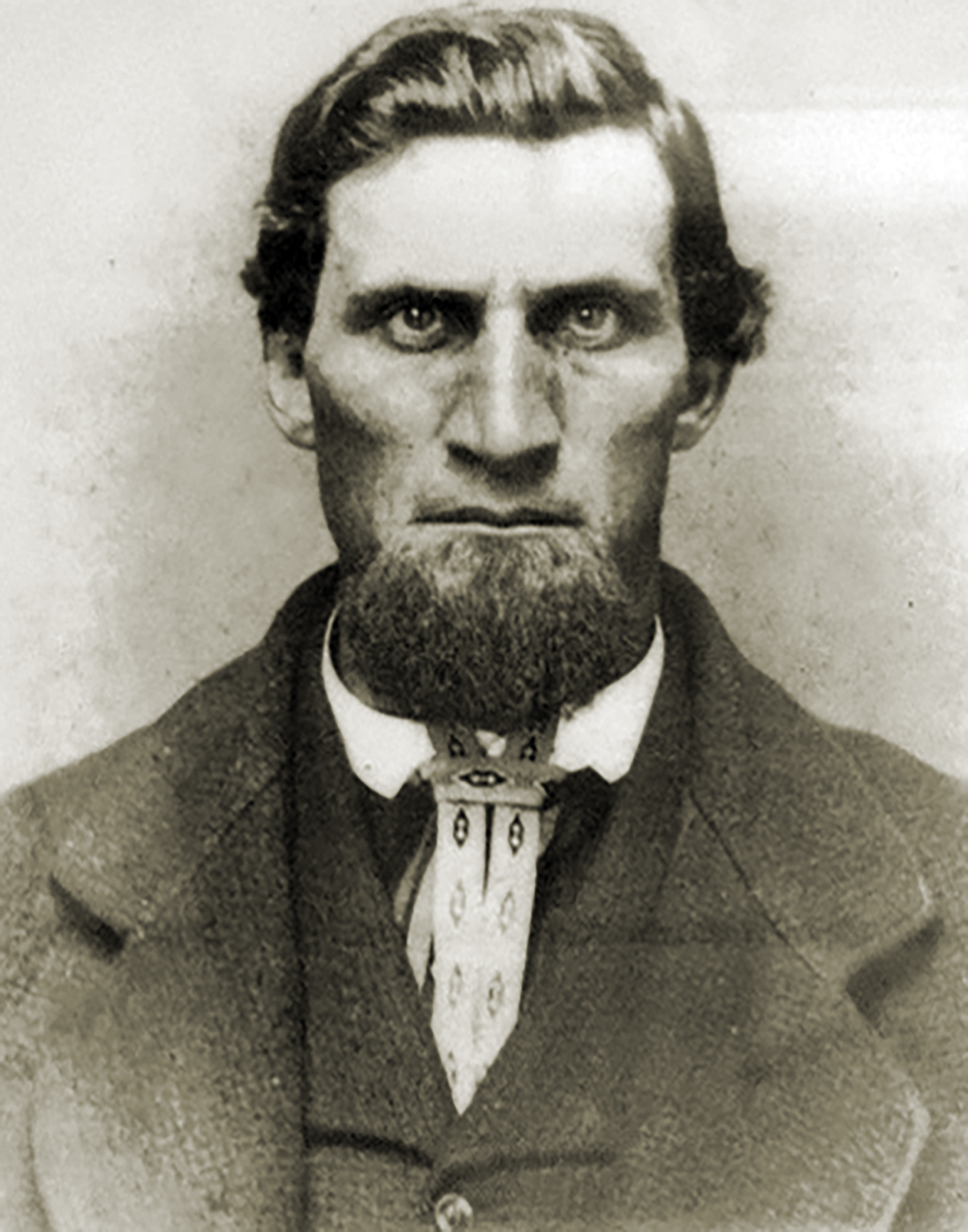

The first “Buffalo Bill” was a Kansas frontiersman, well known in his time but never a living legend. In his youth, he rode and trapped with Christopher “Kit” Carson. A familiar figure at Bent’s Fort and Fort St. Vrain, he traded with Indians on the central Plains and sometimes fought them. He once beat up Kiowa Chief Satanta (White Bear), warrior and future “Orator of the Plains,” and then became the chief’s trusted friend. He also counted George Armstrong Custer as a friend. Defining the northern end of a famous cattle trail was among his accomplishments, and he was one of the founders of Wichita, Kan. His birth name was William Mathewson.

Born on New Year’s Day 1830 in Triangle, N.Y., Mathewson at 19 jumped at an opportunity that would change his life forever—he joined the Northwestern Fur Company. As he traveled through the still-wild land that would become the Dakotas, Nebraska and Montana, he learned to trap, trade and fight. After two years with the Northwestern Fur Company, he joined a party under the direct command of Kit Carson and set off farther west toward the Rocky Mountains.

In 1852 Mathewson worked at Fort St.Vrain (in present-day central Colorado), a civilian post where he gained insight into business possibilities. He decided to establish a trading post along the Santa Fe Trail near the center of what is now Kansas—at the so-called Great Bend of the Arkansas River. Beginning in 1853, Mathewson was based at the post for 10 years and traded with both emigrants and Indians. Kansas Territory, which included much of present-day Colorado, was created in May 1854.

The summer of 1860 was unusually hot, dry and windy, and the settlers’ crops in eastern Kansas shriveled in the fields. By the bitter winter of 1860-61, many settlers were starving. One day a traveler returning from the West reached the eastern Kansas settlements with a wagon loaded with buffalo meat. Asked where he got all that meat, he replied, “Out at Bill’s.” Naturally, he was asked, “Bill who?” His casual answer: “Oh, just Bill, the buffalo killer out at Big Bend.” Thus, the moniker “Buffalo Bill” was bestowed on William Mathewson.

At his post on the Big Bend of the Arkansas, Buffalo Bill Mathewson generously supplied the needy folks with all the buffalo meat they could carry on horseback or haul in their wagons. Through the winter, he made almost daily trips to the buffalo range, sometimes killing as many as 80 of the big beasts a day to ensure a steady supply of “free” meat. It was six or seven years later that William F. Cody shot enough buffalo near Fort Hays, Kan., to earn the same soubriquet, “Buffalo Bill.”

In 1861 Kiowa Chief Satanta rode to Mathewson’s trading post intending to steal some stock and gain vengeance for a warrior who had been killed while attempting to take a horse from the post. In a heart beat, Mathewson floored Satanta and gave him a thorough beating, before escorting the chief and his followers off the property at gunpoint. From that day on, the Plains Indians in the area called Mathewson “Sinpah Zilbah (Long-Bearded Dangerous White Man). A year later, Satanta presented Mathewson with some of his finest ponies and entered into a treaty with his “friend.” If it was Mathewson’s generosity that impressed the Kansas settlers, it was his relationship with Satanta that made him well known among area Indians.

By the summer of 1864, Buffalo Bill Mathewson had left the post on the Big Bend and moved to a ranch. Life hadn’t become any easier, though. The Indians were on the warpath. Satanta warned Mathewson about the uprising long before raiders struck the ranch. Instead of seeking safer ground, Mathewson and a few other men, each armed with the first breechloading rifles used on the Kansas plains, made a stand. Early on July 20, hundreds of Indians attacked the ranch, but they were met by devastating fire. A three-day impasse ensued, and on the third night, the raiders withdrew after losing some 100 horses and several of their companions.

After getting the warning from Satanta, Mathewson had not only prepared a defense but also had written to both the Overland Transportation Company and Bryant, Banard & Company, advising them not to send out any supply wagons. One supply train of 147 wagons and 155 men had already departed the government posts in New Mexico Territory, however, and was now within three miles of Mathewson’s ranch. From the roof of his ranch, Buffalo Bill saw the Indians attack the wagon train. Leaving his men behind to protect the ranch, he loaded his Sharps rifle and Colt revolvers and rode headlong into the encircled wagons. Grabbing an ax, he broke open some crates in the wagons and distributed weapons and ammunition to the freight men. Under his leadership, the freighters delivered a scathing fire that broke the attack. Mathewson then took a group from the train and chased the retreating Indians.

Not long afterward, on August 28, 1864, Mathewson married Elizabeth Inman, who had emigrated from Yorkshire, England, in 1850. Becoming a married man didn’t mean Buffalo Bill would change his lifestyle. He taught Lizzie how to handle firearms, and she became his steadfast companion on trading expeditions. Later, she and a friend, Miss Fannie Cox of St. Joseph, Mo., would accompany him on the new Chisholm Trail—the first two white woman to do so. The Indians who visited the Mathewsons’ ranch/trading post called Lizzie “Marrwissa” (Golden Hair).

At the end of the Civil War, the Federal government requested that the commander of the Western Department find someone to contact the hostile Indians and arrange a council. The obvious choice was Mathewson, who discovered an Indian camp at the mouth of the Little Arkansas River and managed to arrange a council between the government commissioners and Indian leaders. In 1867, however, the Indians were back on the warpath in Kansas. After assessing the situation, Mathewson telegraphed Washington, requesting that General Winfield Scott Hancock and his troops be withdrawn from the area and stating that he would try to contact the Indians himself.

This request was granted, and Mathewson convinced the Indians to meet with government representatives. The result was the Medicine Lodge Treaty, in which the southern Plains tribes were assigned reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

That same year, Buffalo Bill took two boys he had rescued from the Comanches to Fort Arbuckle in Indian Territory. Upon delivering the youths, Mathewson ran into Colonel Henry Dougherty, who was moving a cattle herd north from Texas. Dougherty asked Mathewson to be his guide, and Mathewson led him over the northern portion of what then was called “Chisholm’s Trail,” bringing the first herd of Texas Longhorns to the Wichita area. After the railroad arrived in Wichita in 1872, the town became the major cattle shipping hub of Kansas, and Chisholm’s Trail became the famous Chisholm Trail.

Also during the 1860s, Mathewson met and frequently visited with an army man stationed in Kansas and destined to become a military icon of the Frontier West—Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, who would die at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory in 1876. Between 1868 and 1873, Mathewson was instrumental in securing the release of 54 white women and children held captive by the Indians. He and his wife settled in the Wichita area, where he built a log home, became a civic leader and established the Wichita Savings Bank in 1887.

Why was William Mathewson not a legend in his own time as was William F. Cody? His lack of national fame was his own choosing. He didn’t view his life as extraordinary; he simply did what needed doing. On numerous occasions Buffalo Bill Mathewson was approached by newspaper and magazine writers and even authors of the popular dime novels wanting to tell the story of his life on the Western frontier. However, Mathewson always rejected the proposals.

When Mathewson died in Wichita on March 22, 1916, he was referred to as “the original Buffalo Bill.” Not long after that, his son, William Mathewson Jr., received a letter from none other than the famous scout-turned-showman Buffalo Bill Cody. The letter voiced Cody’s condolences and acknowledged the fact that fellow frontiersman William Mathewson was truly the first “Buffalo Bill.”

Originally published in the August 2008 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.