Edmund Ruffin’s 1860 book predicted a Civil War from which the South emerged triumphant

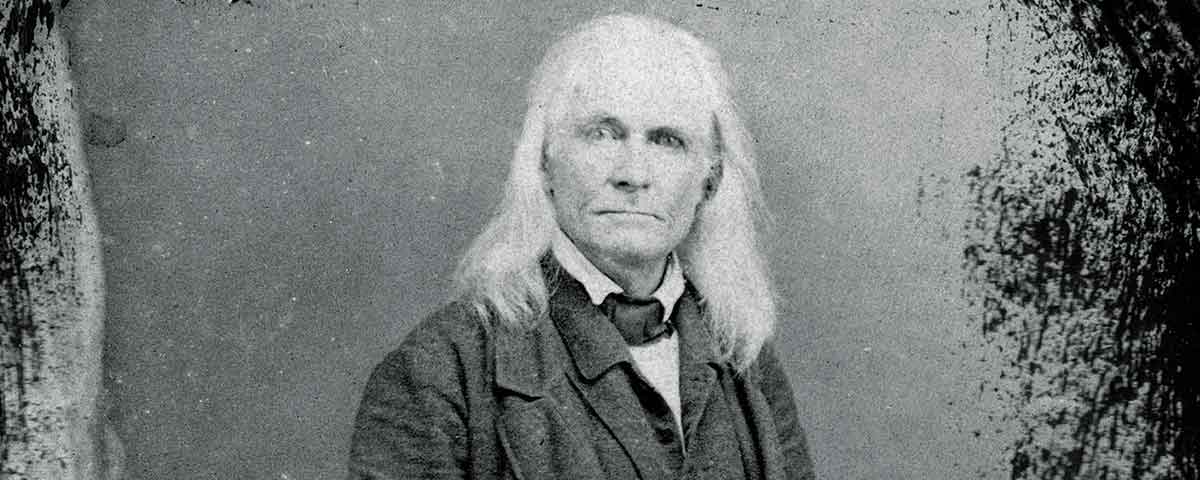

The irony is rich—avid abolitionist John Brown saved the life of Fire-eater Edmund Ruffin, and gave purpose to the Southerner’s life. Ruffin, a wealthy Virginia planter and slaveowner, was known for his scientific study of soil culture, undertaken to help improve and sustain the plantation economy of the South. He became a leading Fire-eater, as Southerners eager to see a separate nation built upon plantations and slavery were known, and by 1859, after decades of espousing Southern nationalism, he despaired of ever seeing his dream come true. In an October 18, 1859, diary entry, he contemplated suicide. The next day, John Brown saved Ruffin’s life. Newspapers for October 19 reported the abolitionist’s failed attempt to capture the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, orchestrated entirely by Northern men.

The news rekindled Ruffin’s hope for a Southern confederacy, and he raced to Charles Town, Va., the site of Brown’s trial, to watch it emerge.

Adapted from LOOMING CIVIL WAR: How Nineteenth-Century Americans Imagined the Future by Jason Phillips. Copyright © 2018 by Oxford University Press and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Can be purchase at www.amazon.com

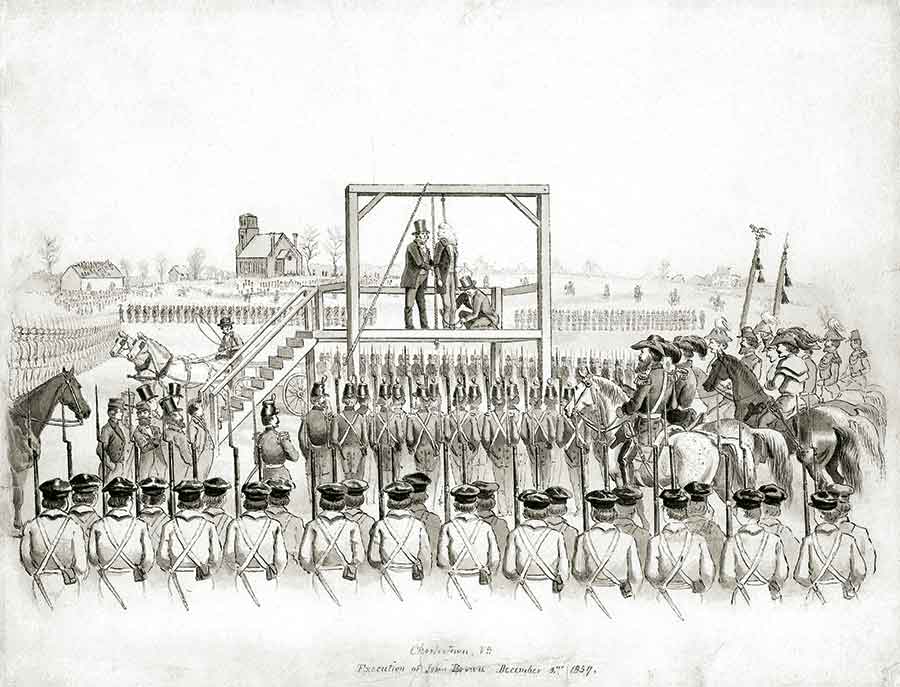

Brown was sentenced to be hanged, and on December 2, 1,500 militamen formed two squares facing his scaffold. Ruffin evaded a strict ban on civilian spectators by becoming, for a day, the oldest cadet of the Virginia Military Institute. The condemned man scaled the steps and Brown requested, “do not detain me any longer than is absolutely necessary.” According to Ruffin, Brown displayed “complete fearlessness of & insensibility to danger and death.”

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]eeks after John Brown’s death, Ruffin picked up a copy of Wild Southern Scenes by John Beauchamp Jones, who would later serve as a clerk for Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The book caught Ruffin’s eye because Jones’ novel anticipated secession and civil war at a time when Brown’s raid raised Ruffin’s hopes for Southern independence.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Ruffin penned over 300 pages in two months. His history of the future foretold secession, Civil War, and southern independence.[/quote]

Jones’ history of the future foretold a violent future in which Southerners would endure an era that would exceed the French Reign of Terror. Northern authorities erected a guillotine in every city and township. Tribunals of Three investigated and executed people suspected of sympathizing with slavery and the South. A Northern tyrant named Ruffleton assumed the title Lord Protector and planned an empire reminiscent of Rome. His Senate would consist of hereditary nobles drawn from the finest families. His subjects would identify themselves as Americans only; all state lines would be erased, all sectional affiliations would vanish within the new empire. The plan failed because Britain joined the war to finish off an old enemy. Stirred by the return of their revolutionary foes, American armies united and repelled Ruffleton’s invaders.

Ruffin, however, felt disappointment when he reached the end of the book to find the Union had been restored and sectionalism dissolved. “A very foolish book,” Ruffin concluded, “which I regret having bought, or spent the time in reading.” But Wild Southern Scenes inspired Ruffin to begin his own Southern fantasy on the eve of the 1860 election, and he set himself to the task to write his own history of the future. In two months, he penned more than 300 pages that foretold secession, civil war, and Southern independence. During a heated election year, the Charleston Mercury printed the first chapters in serial form. Ruffin titled his book Anticipations of the Future, and the text took the form of a series of fictional letters that described how a threatened and deceived South went to war.

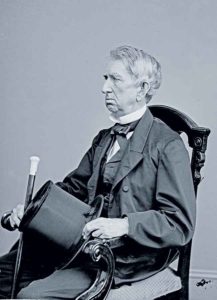

In Ruffin’s history, the real trouble had started in 1864 when New York Senator William Seward replaced Abraham Lincoln as president. To that point, secession had not occurred because Lincoln had not attacked slavery. Lincoln, according to Ruffin, was “praise-worthy, and respected for probity, wisdom, and firmness.” William Seward was different. He persuaded the Republican Congress to serve only Northern interests. They raised tariffs and improved only Northern canals and ports. They commissioned only Yankees as military officers and swelled the Army’s ranks with free labor scum. Meanwhile, Seward packed the Supreme Court with abolitionists.

The value of slavery in the border South plummeted, because runaways knew Seward’s administration would ignore the 1850 federal Fugitive Slave Law, which required captured escaped slaves be returned to their owners. In diplomacy, the government acknowledged the sovereignty of Haiti, formed by a slave revolt, and Liberia, an African republic in part populated by former slaves sent there by the American Colonization Society. Haitians wasted no time sending a minister to America, “a stout, burly negro, of clumsy frame” who called himself the Duke of Marmalade. All this time, Southerners loudly protested, but did nothing. Without bold action to back their fiery language, Northern politicians saw Southern statesmen as fragile to men.

In 1867, six states—New York, Ohio, Michigan, Minnesota, Kansas, and California—voted behind closed doors to split in two, thereby adding 12 abolitionist Senators and giving Republicans the three/fourths majority needed to abolish slavery. In 1868, Seward won reelection unopposed. The events finally convinced six Deep South states to secede on Christmas Eve, 1868. That night South Carolina captured Fort Sumter without a single casualty. Virginia and the Upper South remained in the Union, but they warned the federal government not to tread upon their soil. When Seward sent an army through western Virginia, Old Dominion troops repulsed it and the state seceded. The rest of the South followed, except for Texas.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Civil War finally erupted in the summer of 1868. Northern armies of abolitionists invaded the South. William Lloyd Garrison, the fiery leader of the American Anti-Slavery Society, captained one group of 700 whites and blacks who sailed five ships to Maryland. Their cargo included 10,000 muskets and 5,000 pikes to arm the slaves. But Southern disaster was averted, Ruffin wrote, because “If the plotters had known anything of negro human nature, they might have been sure that any such conspiracy, if confided to as many as fifty negroes, would necessarily be discovered and betrayed.” Southerners knew Garrison was coming three days before he arrived. Concealed along the shoreline, defenders fired into Garrison’s men after they disembarked. Preachers and abolitionist lecturers who came along for the adventure fled for their boats and were stabbed to death in the surf. Southerners singled out Garrison, “the apostle of insurrection and massacre,” and hanged him.

A much larger abolitionist army led by Owen Brown, John Brown’s son, invaded Kentucky. They butchered men, women, and children “after the infliction of still greater horrors.” During their first night back in the South, disenchanted black soldiers deserted in the hopes of returning to their former masters. “Like all other northerners, Brown was entirely ignorant of the peculiarities of negro nature, disposition, and character.” An army of white Kentuckians surrounded Brown’s dwindling force, massacred the Yankees, rounded up the remaining former slaves and returned them to bondage. Kentuckians hanged Brown and 27 officers from a giant oak, leaving their carcasses for the birds. The executioners were a number of black prisoners “who, when invited, readily volunteered to perform the…duty, and appeared to enjoy” hanging their former allies.

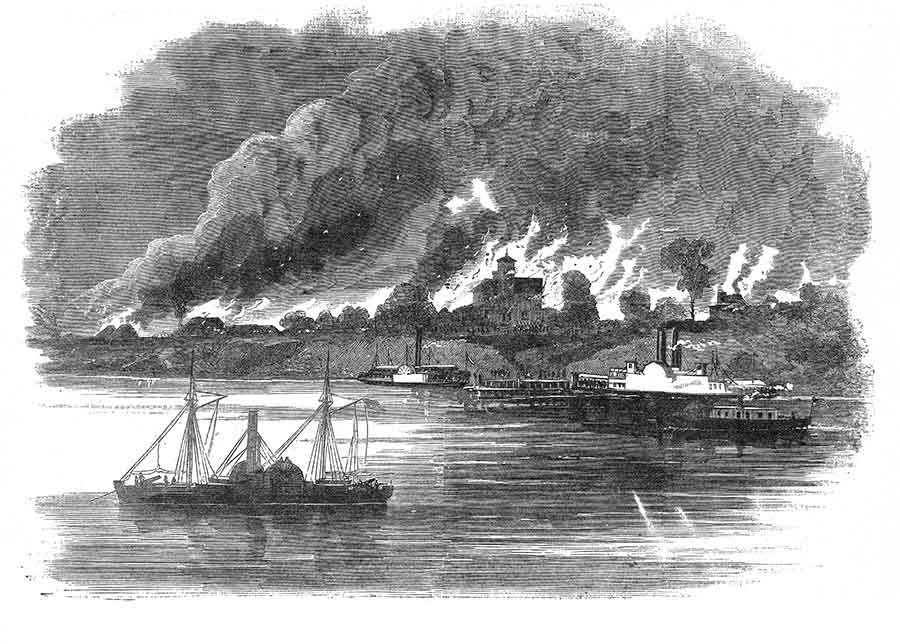

Meanwhile, conditions deteriorated on the Northern home front. Without Southern commerce, thousands of Northern workers lost their jobs and took to the streets and 40,000 rioters attacked New York City. The government sent 4,000 Regular soldiers into the melee. One thousand fought desperately and died in the streets. Three thousand joined the mob. By nightfall the horde controlled the city and torched it. More than a million New Yorkers burned to death under “one raging sea of flame, rising in billows and breakers above the tops of the houses.”

Thugs attempted the same thing in Philadelphia, but reliable military forces fired artillery shells into the crowds and slaughtered thousands. A Boston mob proved more successful. In addition to plundering the city, they hunted down and lynched prominent abolitionists. In Washington, D.C., the government fled the capital after Virginia and Maryland seceded. The United States set up a temporary seat of power in Albany, while the Confederacy claimed Washington for its own capital. The only noticeable change in the District was a new law expelling free negroes. Most blacks stayed in the city, however, because they voluntarily returned to slavery.

On September 20, 1868, the North requested a truce. The terms did not recognize Southern independence, but it was an established fact nonetheless. The United States was so crippled by this short, destructive war that another wave of secession seemed imminent. In time, the West and Mid-Atlantic would join the stronger Confederacy, leaving fanatical New England alone, poor, and irrelevant.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s Ruffin wrote his book, he consulted The Partisan Leader by Nathaniel Beverley Tucker, Ruffin’s friend and distant cousin. A law professor at William and Mary, Tucker set the standard for Southern histories of the future when his 1836 book predicted that Martin Van Buren sought the presidency to secure Northern dominion over the South. Like Ruffin, Tucker timed his publication in an attempt to influence the presidential election. Tucker warned that Van Buren conspired to turn the presidency into a dictatorship by creating a sectional majority party that would help him win an unprecedented third term of office.

When Van Buren accomplished his plan in The Partisan Leader, the South coordinated a swift secession movement and formed a separate nation. The Southern Confederacy preserved the legacy of the Revolution, the spirit of the Union, and the Constitution. Virginia hesitated to secede, unsure about abandoning the nation it sired, and a nasty guerrilla war ensued that tested the allegiance of every Virginian and decided the fate of free government in America.

In 1861, Ruffin’s Civil War prophecy became reality, and he traveled to the scene of action in South Carolina to stare at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor and live his imagined future. It was the most gratifying experience of his life. During the summer of 1860, he had acquired detailed information about the harbor and fort from friends in the federal government. When rumors swirled that the Confederates would resist attempts to supply the fort’s garrison on April 8, Ruffin raced to the Citadel, borrowed a musket, and boarded a steamboat to be in the harbor when the war he anticipated began. Nothing happened. The following morning he embarked with a boatload of volunteers for the Confederate batteries at Morris Island.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The spectacle of an old man with long white hair clutching a musket and eager to fight drew a crowd.[/quote]

The spectacle of an old man with long white hair clutching a musket and eager to fight drew a crowd, and commanders of many regiments urged Ruffin to join their unit. He chose the Palmetto Guards because he anticipated that their position would be in the center of the looming battle. He was right. When drumbeats summoned men to their positions before dawn on April 12, 1861, Ruffin fired one of the first shots of the war. The shell struck the northeast parapet and the other Confederate batteries that ringed Charleston Harbor opened fire. When Major Robert Anderson surrendered the fort, Ruffin carried the Palmetto Guards’ flag at the ceremony. To mark the historic event, he picked through the debris, pocketing shell fragments and, when no one was looking, cut a swatch of fabric from the first Confederate flag to fly over conquered territory. History seemed to be happening exactly as Ruffin prophesied.

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]e would not miss the war he anticipated for the world. In July 1861, carrying cheese, crackers, blankets, and shoes, he hurried to the camps near Manassas, Va., to join his Fort Sumter comrades, the Palmetto Guards. Everything seemed to be unfolding just as he had anticipated in Anticipations of the Future. When he heard rumors of Yankee atrocities, Ruffin accepted them as fact. He wanted the Confederacy to pursue the strategy that worked in his history of the future: guerrilla warfare without quarter. Merry sounds around campfires, laughter, and martial music convinced him that he belonged to a great army, a band of knights. The finer elements of the South had stepped forward to make history.

But his body ached from sleeping on the ground and his new shoes tortured his feet. As the Palmetto Guards marched from one position to the next, Ruffin fell behind. He asked to ride with artillery crews and caught up with his company but was too tired to be of service. The active campaigning exposed his body’s inability to fight like an eager young volunteer. Nonetheless, when the First Battle of Manassas erupted on July 21, 1861, Ruffin was determined to be at the center of it.

But Union troops did not attack the Guards’ position, and Ruffin sat impatiently, galled to be “confined to one spot all day, between a high hill & thick woods, where nothing could be seen.” The white-haired soldier “became so excited with the sounds of the firing” that he deserted his post for the seat of war. A Confederate artillery battery spotted him and took him forward to a vantage point from where he spied a ragged blue line retreating. The old man gratefully accepted an offer to fire a shell that exploded among men scurrying to cross a bridge. Ruffin watched as panicked survivors fled from the carnage he caused.

After the battle, he walked to the spot where his shell landed, collected battle trophies, and counted the dead. Only three bodies remained. Disappointed, Ruffin convinced himself that he killed or wounded at least 15 Yankees. He predicted that the victory at Bull Run “would be virtually the close of the war.” In Anticipations of the Future, Ruffin imagined Northern armies bleeding to death in costly invasions of the South. Union aggression would cause “the impossibility of conveying reinforcements and supplies to the seat of war.” Then, as Northern society descended into anarchy, troops would be needed to suppress insurrections at home. He was impatient for that, and even wished for death in 1861. If only a cannonball had painlessly killed him at Bull Run, just as he had done to his enemies. Nothing would be better for his legacy than to die like John Brown, a willing sacrifice at the dawn of his cause.

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]ying at Bull Run would have saved Ruffin from a reckoning. He gravely misunderstood the motivations and mindset of African Americans. He was surprised to learn that slaves escaped as soon as the enemy approached. “The number, & general spreading of such abscondings of slaves are far beyond any previous conceptions,” he admitted. The war exposed Ruffin’s delusions that slaves preferred bondage to freedom and, for the first time in his life, Ruffin armed himself against the likelihood of a slave revolt. When the Army of the Potomac approached his home on the peninsula east of Richmond in May 1862, Ruffin expected slaves to rise up against him. “We prepared & loaded our fire-arms—& for the first time I even locked my room (which is also an out-door,) & closed & fastened the very frail window shutters, when I went to bed.” In 1862, one of his slaves, William, a carriage driver, fled to the Union Army.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Dying at Bull run would have saved Ruffin from a Reckoning.[/quote]

While his slaves turned against him, so did the war Ruffin worked so hard to create. The spring 1862 Peninsula Campaign ruined Ruffin’s future, because the enemy’s approach compelled him and his family to abandon three of their plantations in the Richmond vicinity. Ruffin, a man who had personified precipitate action when he rushed toward the conflict by volunteering at Harpers Ferry, Charleston, and Manassas, became a refugee of the war. The enemy hunted him as an outlaw and ringleader of secession. For three years, he and his family traveled across war-torn Virginia seeking a haven from the enemy for themselves and their remaining slaves. Ruffin realized that the fame he achieved in 1861 endangered his family.

Ruffin had collected battle trophies; now Union troops looted his belongings to signify the doom of secession. During the course of the war, the enemy destroyed all three plantations that Ruffin evacuated. They liberated slaves, trampled fields, burned fence rails, confiscated animals and grain, wrecked machinery, girdled trees, broke windows and doors, slashed furniture, looted his library, and carried off his private papers. Graffiti on the walls of his home read, “You did fire the first gun on Sumter, you traitor son of a bitch.” “Old Ruffin, don’t you wish you had left the Southern Confederacy go to Hell (where it will go) and had stayed at home,” read another scrawled insult.

The glory that Ruffin so confidently anticipated failed to materialize. Instead the looming war ruined him and stole his future. His children had warned him of this fate before he fired the first shot. Edmund Jr., Julian, Elizabeth, and Mildred forecast doom. By 1865 only his namesake survived.

Confederate surrender shattered Edmund Ruffin and his prophecy. His anticipations shaped his reality by presupposing the war’s scale, decisive factors, and outcomes. The alternative reality he expressed in Anticipations of the Future affected how Ruffin interpreted events and acted during the conflict. When the war erased Ruffin’s future, it radically redefined his life’s work. He had told William Yancey before secession, “I would stake my life on the venture,” and he did. Things did not go as planned. Defeat robbed Ruffin of his anticipated future as a national founder. Worse, the war disproved his claims to read the future.

Ruffin raged against the ending he did not foresee and could not accept. Looking to the future, Ruffin tried to prophesy one last time. He predicted a “far-distant day shall arrive for just retribution for Yankee usurpation, oppression, & atrocious outrages—& for deliverance & vengeance for the now ruined, subjugated, & enslaved Southern States!” Too old to participate in this vague reckoning to come, Ruffin chose not to meet his fate. His contempt for the present mixed with his proactive bent to form a lethal combination. Unwilling to become a burden to his children and a subject to Yankee rule, Ruffin took control of his future. Sitting in his private room at his son’s house, Ruffin waited for visitors to depart, noted the time on his watch, 12:15 p.m., bequeathed the timepiece to his grandson, rested his chin on the barrel of a shotgun, and pulled the trigger.

Jason Phillips is the Eberly Family Professor of Civil War Studies at West Virginia University. This article is adapted from his new book, Looming Civil War: How Nineteenth-Century Americans Imagined the Future. Copyright © 2018 by Oxford University Press and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.