For every outstanding aircraft design that achieved fame during World War II, there was another that did not—usually a victim of circumstance, best summed up with the all-too-familiar adage, “too little, too late.” Unique among those might-have-beens is the VL Pyörremyrsky, a one-of-a-kind prototype fighter whose only victory was against the ravages of time.

The final few months of 1942 were full of ominous events for the Axis powers, as the tide of war turned against them at places called El Alamein, Guadalcanal and Stalingrad. In the air, a new generation of British, American and Soviet aircraft arose to challenge the air arms of the Axis powers. One of these was the Soviet Lavochkin La-5 fighter, a radial-engine development of the LaGG-3 that was disturbingly superior in performance.

The appearance of La-5s over the Soviet northern front caused particular alarm in Finland’s air force, the Suomen Ilmavoimat. Since Finland had resumed hostilities against the Soviet Union on June 25, 1942, the Ilmavoimat had been holding its own with a hodgepodge of imported fighters such as the American-built Brewster B-239 and Curtiss H-75A Hawk, the French Morane-Saulnier M.S.406, the Italian Fiat G.50, and the Dutch Fokker D.XXI. Superb training and motivation had helped the Finnish pilots to prevail over their more numerous Soviet opponents during that time, but the prospect of facing hordes of improved Soviet aircraft made it clear that the Finns would need newer aircraft of their own.

The Finnish government instructed the State Aircraft Factory (Valtion Lentokonetehdas, or VL) to place maximum priority on the design and construction of two prototypes of a modern fighter. The new plane would have to make maximum use of indigenous materials, be able to serve in both interception and ground attack roles, and be durable enough to operate from small front-line airfields under the most severe climatic conditions.

VL was not exactly new to the field of aircraft development. By 1939, it had developed nine aircraft types, and it had just begun to tool up for series production of the Myrsky (“storm”) single-seat fighter. The aircraft was powered by a 1,065-hp Pratt & Whitney SC3-G Twin Wasp (bought from the Germans, who had captured a great number of the engines in the course of their earlier conquests). The Myrsky was plagued by numerous structural weaknesses, however, and the final production model, the Myrsky II, proved to be a disappointment—no match for the La-5 and other modern Soviet fighters. The development of a more advanced successor became a vital matter.

The task of designing the new fighter, which was to be called Pyörremyrsky (“whirlwind”), was entrusted to engineer Torsti R. Verkkola. A 1935 graduate of the Technical University of Finland, Verkkola had undertaken postgraduate studies in Berlin before joining VL in 1937. There, he had assisted in the design of several aircraft, aiding engineer Arvo Ylinen with the Pyry (“snow flurry”) advanced trainer, and collaborating with Ylinen and VL’s chief designer, E. Wegelius, on the Myrsky.

Creating a new fighter from scratch is never easy. In the Myrsky’s initial form, the wing tended to bend under stress, and defective bonding had resulted in the plywood skin peeling off. Two fatal crashes were eventually found to have been the result of tailplane flutter, necessitating the redesign of both wing and horizontal tail surfaces.

Nevertheless, the VL staff had learned a lot from that experience, not the least of which was another adage: “Haste makes waste.” Consequently, despite the urgency attached to the development of the Myrsky’s successor, Verkkola and his team exercised a lot more care in designing it, especially in their analyses of stress and weight factors.

Early in March 1943, Finnish pilots ferried over 16 Messerschmitt Me-109G-2s—the first of several batches of German fighters (48 Me-109G-2s, 112 Me-109G-6s and two Me-109G-8s) that would eventually supplant, though not entirely eclipse, the older fighters. With the Messerschmitts came stocks of their engine, the 12-cylinder inverted-vee, liquid-cooled Daimler-Benz DB 605, which became the logical choice for the new Finnish design.

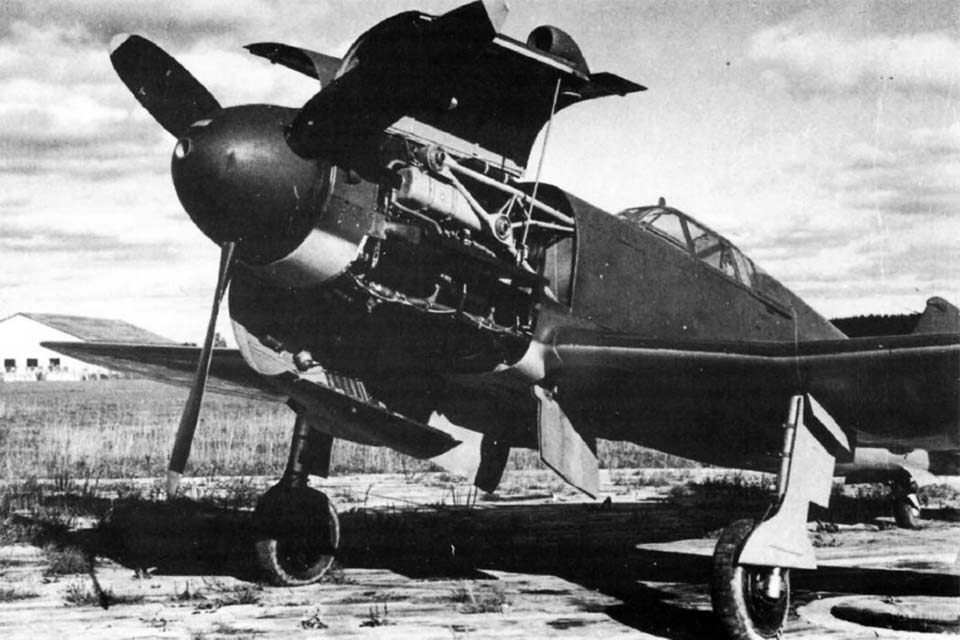

After the Ilmavoimat had considered five different proposals, the VL design team began to build an exceptionally clean, compact prototype around the DB 605 and a VDM three-bladed, metal constant-speed propeller. Not too surprisingly, the Pyörremyrsky’s nose bore a striking similarity to that of an Me-109G-2, but the resemblance ended there. The forward part of the Pyörremyrsky’s fuselage consisted of a chrome-molybdenum steel-tube frame covered by detachable metal panels, while the rear, which included the vertical stabilizer, was a wooden monocoque structure of pine and plywood. The ailerons, elevators and rudder were metal-framed and fabric-covered. The wings were built over single wooden spars and skinned in plywood, with electrically operated, light-alloy flaps. The upper surfaces of the wings’ inboard sections had a few degrees of anhedral, giving the whole assembly a subtle inverted-gull appearance.

The relatively spacious cockpit, similar to the Myrsky’s, was enclosed by an aft-sliding canopy. Aft protection was provided by a 10mm armor bulkhead immediately behind the seat. Most instrumentation was of Finnish manufacture, but the radio was a German FuG VIIa. A self-sealing tank behind the armored bulkhead held about 101 gallons of fuel, which could be supplemented by two 33-gallon drop tanks under the wing. Armament was to have been an engine-mounted 20mm MG 151 cannon and two 12.7mm LKK-42 machine guns in the upper decking of the fuselage nose, although they were never fitted. For the close-support role, provision was made for two 441-pound bombs under the wing.

The Pyörremyrsky order had been reduced from two to only the one by 1944—and work on the existing prototype was proceeding slowly. Regardless of Finland’s need for the new fighter, the overworked State Aircraft Factory simply had too many other things to do. In the first eight months of 1944, VL was also busily engaged in getting the Myrsky II into full production while converting Morane-Saulnier M.S.406s into Mörkö-Moranes (“Ghost Moranes”) with captured Soviet 1,100-hp Klimov VK-105P engines.

Recommended for you

The factory also had to overhaul and repair Finland’s existing front-line aircraft amid desperate fighting that reached its peak over the Karelian Isthmus during the summer of 1944. On September 4, 1944, the Finnish government was compelled to accept Soviet armistice terms, at which point work on the Pyörremyrsky prototype, which had been languishing for several months, came to a complete halt.

After helping to drive out German forces from Finland in accordance with the armistice terms, most Ilmavoimat units returned to their peacetime bases on January 20, 1945. Soon after that, VL, somewhat surprisingly, resumed work on the Pyörremyrsky. A DB 605 AC engine, removed from an Me-109G and overhauled, was installed in the prototype airframe and was rated at 1,475 hp for takeoff and 1,355 hp at 18,700 feet. Empty weight was 5,774 pounds, while normal loaded weight would have been 7,297 pounds. Its wingspan was 34 feet 2⁄3 inches, wing area 204.514 square feet, length 32 feet 33⁄4 inches, and height 12 feet 91⁄4 inches.

Preliminary taxiing trials took place at Tampere, and the prototype, bearing the serial number PM-1, flew for the first time on November 21, 1945, with VL’s chief test pilot, Captain Esko Halme, in the cockpit. Despite the care that had gone into the plane’s design, its maiden flight was almost its last, as parts of the cowling fell off and exhaust fumes filled the cockpit. Halme almost lost consciousness before he was able to use his oxygen gear.

With its wider-track landing gear, the Pyörremyrsky’s taxiing and takeoff characteristics were markedly superior to the Me-109’s. Once in the air, Halme reported that its controls were too light and “caught” at higher speeds, while the rudder was too heavy and the center of gravity was too far aft. Those problems aside, however, his general opinion was positive. He rated overall maneuverability as superior to that of the Me-109G-6. During speed and climb trials, Halme recorded a maximum speed of 324 mph at sea level and 385 mph at 21,000 feet. The Pyörremyrsky could reach an altitude of 16,400 feet in 5 minutes 30 seconds, and its calculated service ceiling was 39,910 feet. The normal flight endurance of 1 hour 50 minutes could be extended to about 21⁄2 hours using the auxiliary drop tanks.

After the PM-1’s first flight, VL devoted 2,300 design hours and 6,400 workshop hours to ironing out its shortcomings. Engine mounting bolts had fractured, the landing gear had malfunctioned and the electric system was troublesome. Consequently, the landing gear and flap electric motors were replaced—the latter with those of the Bell P-39 Airacobra. The inner landing gear doors were removed entirely. The tailplane trim mechanism was redesigned.

Seven other test pilots put the Pyörremyrsky through a total of 42 flights and 27 hours of flight time. During that time, the prototype’s problems were largely eradicated, but by then the whole test program was no more than an academic exercise. The postwar Ilmavoimat’s fighter component had been drastically reduced. As far as the replacement of its Me-109Gs was concerned, something other than the no longer available Daimler-Benz DB 605 was needed, and in the case of the Pyörremyrsky, that would require costly redesign.

Thus, the Pyörremyrsky program was terminated in 1947, with only test pilot Halme to testify to its potential. “It was undoubtedly one of the most pleasant and efficient piston-engined aircraft I have ever piloted,” he commented years later. “If only it had been available in quantity in the summer of 1944!”

The Pyörremyrsky remained intact until April 1, 1953, when an official decision led to its dismantlement. Its more useful components, such as instruments, were auctioned off at the Finnish air force depot at Tampere. The DB 605 engine was packed in a case, while the airframe was placed in cold storage at Kuorevesi. The aircraft’s remains were later left out in the open, but then were put back in cold storage at Tampere.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

In 1970, a small contingent of workers at the Air Force Depot began to express the desire to restore some of the historic aircraft. They eventually received the government’s blessing to use certain facilities for the project—provided that the work be done only in their free time. The ad hoc committee that embarked on the project included two depot inspectors, a storekeeper, a mechanic and a staff sergeant. The first object of their attention was the Pyörremyrsky, despite the fact that its airframe had by then greatly deteriorated.

The Pyörremyrsky’s wooden wings were moved from the storage hut to a hangar at the end of April. Photographs and color samples were taken to provide accurate reference once the fighter was repainted and its markings reapplied. The entire aircraft was then disassembled and all parts cleaned and repaired, while a list of missing items was compiled and a search was begun for replacements. Captain Halme offered help and advice to the team, and various Finnish companies assisted.

The original DB 605 AC engine was found, though its exhaust manifolds were missing. Fortunately, a search of Me-109Gs in scrapyards all over northern Finland yielded the necessary replacements. During final assembly of the aircraft, the restorers found, to their dismay, that they could not attach the engine cowlings because the appropriate locking fittings were missing. They were eventually discovered under an old car in a junkyard in Jamsa.

In all, the dedicated team spent some 1,240 hours restoring the Pyörremyrsky, which was completed in October 1972. On August 19, 1980, a Mil Mi-8 helicopter transported it to the Central Finland Aviation Museum at Tikkakoski, near Jyväskylä, where it can be seen today.

Too late to see combat, the Pyörremyrsky nevertheless represented a great aeronautical achievement for a small, overworked aircraft manufacturer learning its business amid unimaginable wartime duress. The surviving prototype stands to equal degree as a monument to the dedication of a team of enthusiasts who devoted as much care to resurrecting it as the design team had devoted to developing it. As such, the VL Pyörremyrsky is a unique airplane well worth preserving.