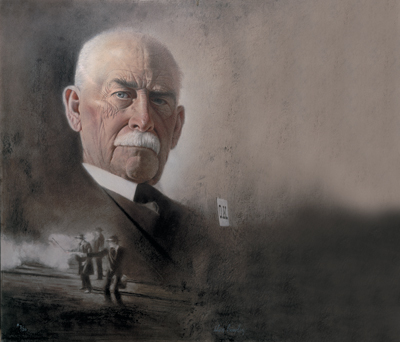

Wherever Clay Allison rode, he carried a reputation with him. “Probably the worst man who ever lived in the West was Clay Allison,” former Dodge City prosecuting attorney Ed Colborn recalled. “He was saturated with every criminal instinct and feared nothing.”

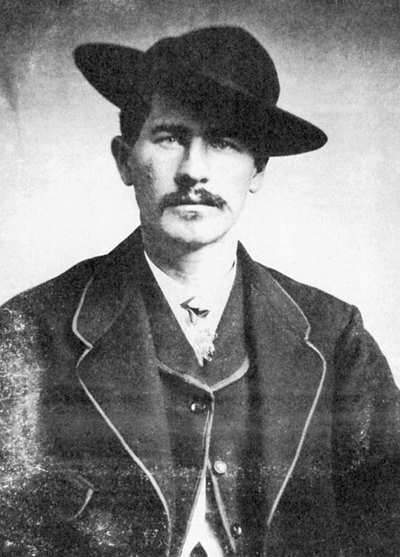

So when Allison rode into Dodge in the fall of 1878, he brought much trepidation to the folks of that dusty cow town on the Kansas plains. An enduring question remains from his visit: Did Wyatt Earp back down Clay Allison? Did the lawman confront the infamous shootist and demand he leave town, relying on courage and the steel of his personality more than the steel of his six-shooter?

Stuart Lake, Earp’s 1931 biographer, told how the marshal fearlessly faced down Allison in the middle of Front Street. In Lake’s telling, Earp drew his .45 so quickly that none in the crowd of onlookers even saw the six-shooter leave its holster. Shoving the muzzle into Allison’s ribs, the tough-talking lawman then demanded the gunman get out of Dodge. Allison complied rather than face Earp’s wrath.

It was an amazing tale, filled with glory and triumph—the type of story that grabs a reader and shows him the makings of frontier courage. It was the elevation of Wyatt Earp.

It was preposterous.

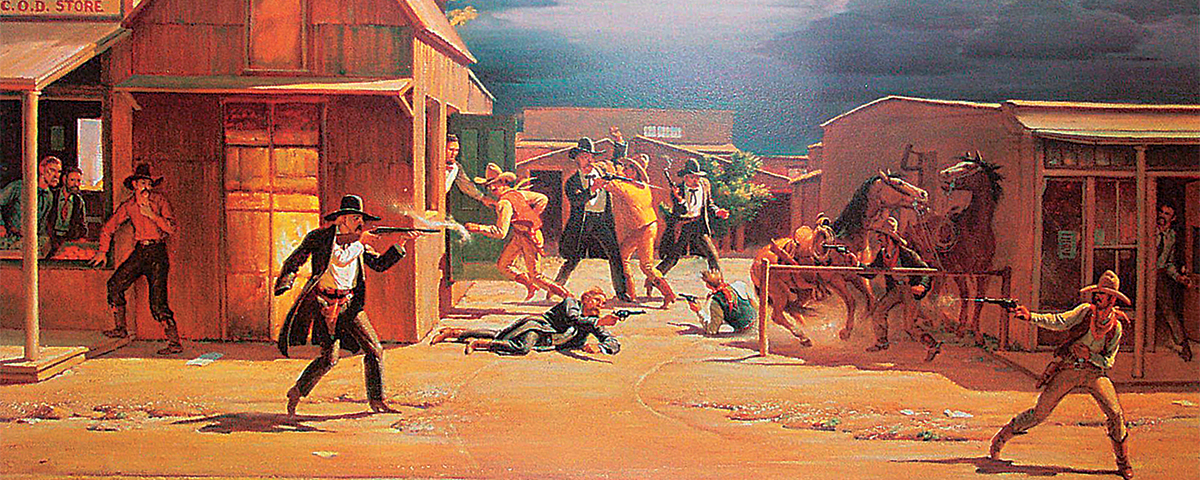

Almost from the moment Wyatt Earp, his brothers and Dr. John Henry “Doc” Holliday left the killing field near the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, on Oct. 26, 1881, people have circulated stories and legends about them. At different times, in different publications, Earp has been either vilified as a murderer and outlaw or glorified as the courageous symbol of the best in frontier grit. That contradiction has gripped Western history buffs. Was Earp a hero? Was he a villain? Was he something in between those extremes? And what about the specifics: Did he back down Allison? Did he fire on surrendering men in the legendary Tombstone gunfight?

As the decades pass, historians unearth ever more information in their search for a fuller understanding of Earp and his times. A cadre of especially diligent researchers has discovered previously unknown details about the lawman and the events that shaped his noteworthy life on the American frontier.

Earp made national headlines after the 1881 standoff known to history as the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral and the ensuing Vendetta Ride, in which he chased down the men he suspected of being involved in the assassination of brother Morgan and attempted assassination of brother Virgil. Within a decade newspapers up and down the East Coast ran fanciful articles that painted him as either villain or hero, vastly confusing his legacy.

Authors followed suit. First, Walter Noble Burns in 1927, then Lake in 1931, portrayed Earp as a hero in their respective bestselling biographies. Lake’s book, Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, exaggerated the lawman’s deeds and created a sort of frontier superhero. In the 1950s and ’60s a new wave of writers, led by Frank Waters, came along to debunk both the heroic myths and the claims Earp had been an unregenerate scalawag. Then came Glenn Boyer, who seemed to provide balance. But Boyer turned out to be the biggest hoaxer of them all, fabricating material and further muddying the waters.

The initial public perception of Earp had been fashioned on frauds and fantasies. Strange as it seems, researchers almost had to start over in their quest to learn the truth about the lawman and his associates in Dodge City, Tombstone and other frontier towns.

Another generation of researchers came to the forefront in the 1990s, searching for hard evidence rather than recycling the timeworn tales. Much new material appeared in my 1997 biography, Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend. Subsequent researchers have pored over old records and newspaper files, hunted through libraries and historical archives and exploited online resources. It is without question the most exciting time in Earp studies since the guns went off in the streets of Tombstone.

The discoveries have been exhilarating, some changing the way we regard the subject. The most salacious revelation is that Earp spent a good amount of time working in brothels along the Illinois River during the period in which Stuart Lake claimed he had been hunting buffalo on the plains. As presented by the late historian Roger Jay in the August 2003 Wild West, Earp went through quite a difficult period after the death of his first wife. He eventually landed in Peoria, Ill., where he worked in brothels, spent time in jail and lived with a 17-year-old prostitute who identified herself as Sarah Earp. Wyatt later worked on a brothel barge that plied the Illinois.

Before arriving in Peoria, Earp had had other scrapes with the law. He’d been arrested for horse stealing in Oklahoma Territory and jailed in Van Buren, Ark. For years no one could determine the outcome of the case, until Georgia writer Gary Roberts dug through documents and learned Earp had escaped. Oklahoman Roy Young then intensely researched the escape and presented the dramatic story. After spending 31 days in a dank cell, Earp with five cellmates pried through the wooden ceiling to the jail attic, pounded a hole in the stone outer wall, tied their blankets together, clambered down 20 feet to the ground and escaped into the night. A jury later acquitted one of the men accused of stealing horses with Earp, so authorities presumably canceled the warrants against Wyatt, though historians have yet to find evidence to prove it.

The incident was a rather inauspicious start for the man who became a symbol of law and order for future generations and whose reputed exploits played across the big screen and in the popular television show The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, for which Lake served as a consultant. Once Earp realized that enforcing the law brought more desirable results than breaking it, he engaged in a series of adventures Lake would glorify and exaggerate, leaving the rest of us to wonder what really had happened.

The infamous 1881 gunfight, which quickly unfolded on Fremont Street and in an empty lot near the rear entrance of the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, remains one of the most controversial episodes in Western history. From the time the bullets flew, aficionados have debated whether the Earps and Holliday were justified in their actions. During the preliminary hearing before Justice Wells Spicer (since known as the Spicer Hearing) a parade of witnesses came forth claiming brothers Wyatt, Virgil and Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday had fired on Frank and Tom McLaury and Ike and Billy Clanton as the so-called “Cowboys” sought to surrender. Perhaps the two most convincing witnesses were Cochise County Sheriff John Behan and Tombstone resident Billy Allen, neither of whom publicly identified with the Cowboy crowd at the time of the fight. Behan said he watched the Earps draw and fire the first shots; Allen said he saw the Clantons and McLaurys extend their hands, as if to surrender.

But new information from Roberts and Nevada researcher Robin Andrews has tainted both witnesses. Roberts found a newspaper article about the gunfight that mentions Harry Woods was out of town at the time. This is important because Woods served as both publisher of the Tombstone Daily Nugget and undersheriff to Behan. With Woods away, the reporting was left to Nugget city editor Richard Rule, a highly competent and objective journalist. That fact prompted Roberts and others to re-examine the Nugget article.

The jovial and popular Behan made friends easily. He had earned respect during his first 10 months in office, and most county residents would not expect him to lie. The Nugget article relies on evidence that could only have come from the sheriff and relates Behan’s words and actions. Most important, the article reports the battle began when one of the Cowboys went for his gun, then the Earp party responded. This suggests Behan did not initially finger the Earps for starting the fight. That became a point of contention in the Spicer Hearing, when Tombstone Marshal Virgil Earp insisted Behan had told him he had “done just right,” while Behan denied having made any such statement. The preliminary hearing concluded dramatically when assistant district attorney Winfield Scott Williams took the stand and claimed to have overheard Behan make the statement, essentially calling the sheriff a liar.

When local saloon man and investor Billy Allen testified at the Spicer Hearing, he kicked it off with a bombshell. Allen had no known ties to the Cowboys, thus no apparent reason to lie, yet he claimed to have watched as the Clanton and McLaury brothers extended their empty hands before the Earp party began firing. Other witnesses, including Ike Clanton and Billy Claiborne, made similar claims. Behan testified the Earps had fired the first shots, but as he’d had his back to the Cowboys, he did not know if they’d held out their hands.

Had the Earps fired on surrendering men, it was murder. Had any of the Clantons or McLaurys made even a motion toward their guns, it was justifiable homicide. Wyatt and Virgil Earp insisted the Cowboys never extended their hands. Other witnesses—notably visiting railroad man H.F. Sills and seamstress Addie Borland—supported the Earps’ version of events.

‘The new research raises the likelihood that two of the most critical witnesses against the Earps were fibbing’

Allen’s testimony remained pivotal. While the other “hands up, don’t shoot” witnesses were linked to the Cowboys, he was an ostensibly neutral local businessman. Had he told the truth? If not, why would he lie?

Andrews and Arizona author John Rose provided a likely answer in Rose’s 2015 book Witness at the O.K. Corral: Tombstone’s Billy Allen Le Van. They chronicle the unusual life of Billy Allen, whose full name was William Allen Le Van. Turns out, he was a Civil War deserter with a string of financial disputes who was fleeing criminal charges in Colorado. His past was filled with lies, deceit and cheating. Allen was at the mercy of anyone who desired to blackmail him. While this doesn’t prove he was lying on the witness stand, it certainly calls his credibility into serious question.

The new research raises the likelihood that two of the most critical witnesses against the Earps were fibbing.

Some recent discoveries dispel longstanding myths about the Earps. Frank Waters floated a remarkable story about how James Earp’s comely stepdaughter, Harriet “Hattie” Catchim, had been a catalyst for the feud between the Earps and the Cowboys. According to Waters, Catchim and Tom McLaury had engaged in a Romeo and Juliet romance of secret meetings and forbidden love. Southern Californian Anne E. Collier blasted apart that falsehood with her research, which revealed that Hattie had married first husband Thaddeus Harris early in 1881 and was no longer residing with the Earps. Collier then shared the juicy story of how Hattie left Harris eight years later to take up with wealthy cattleman William Land, prompting Harris to write letters that begged her to return to him.

Major contributions came from Sherry Monahan, whose Mrs. Earp: The Wives and Lovers of the Earp Brothers relates the stories of the women associated with the fighting Earps. Monahan provides transcripts of Louisa Earp’s private letters, which detail her life with husband Morgan and the conflict in Tombstone. These are agonizing to read, as she relates her transition from frontier wife to widow in the aftermath of her husband’s murder.

Ann Kirschner’s Lady at the O.K. Corral provides insights on Wyatt’s common-law wife Josephine and her exceptional life. As a result of such works the Earp women have emerged from their famed husbands’ shadows, revealing the hardships they endured while listening to the echoes of gunfire.

Among other revelations from ongoing research is a better understanding of the outlawry in Cochise County. For much of the last century such Earp historians as Ed Bartholomew have claimed that the extent of the “Cowboy problem” was based on exaggerations—first by Tombstone mayor, postmaster and Epitaph founder John Clum, then by Stuart Lake and other writers—and that the difficulties were little more than those experienced in any other frontier town. That notion has collapsed under the weight of evidence unearthed by Lynn Bailey, Peter Brand, Don Taylor and the late Paul Cool, who demonstrated that crime in Cochise was far more severe than even Lake had imagined in his 1931 biography. Unsealed government records and rediscovered documents show that John Ringo, Curly Bill Brocius, Bob Martin and the rest of the outlaw lot wreaked havoc with their rustling and robberies.

The last two decades of research have provided continual excitement for those who remain riveted by the storied saga of Wyatt Earp. Historians have logged far more discoveries, small and large, than could be listed in a short article. With the advent of online newspaper services and other web tools, a field that once seemed moribund glows with new life as discoveries keep popping up. The more knowledge that emerges, the better our understanding of Earp and his times, as well as the roots of who we are as a people.

So what really happened when Clay Allison came to Dodge City in the fall of 1878? As Stuart Lake told it, his visit ended in a mighty humiliation for the killer. Earp provided a different version in his 1896 interviews with the San Francisco Examiner, claiming he and Bat Masterson had essentially outwitted Allison, as Earp confronted the gunman while Masterson held a shotgun on him, convincing Allison that any move against Earp would mean certain death.

Several months before Earp shared his account in San Francisco, Ed Colborn, then serving as a judge in Salt Lake City, sat down for an interview with The Chicago Chronicle. Dodge City’s onetime prosecuting attorney admitted being perplexed at Earp’s seeming unconcern with Allison’s arrival in town. Opening the door to his office later that morning, the attorney found Masterson inside, standing watch with a repeating rifle. “All at once,” Colborn recalled, “Allison realized that the strange calm meant something. He stuck his spurs into his horse, and away he went.” The statement certainly supports Earp’s 1896 version of the story.

Masterson and Earp had found a clever way to diffuse the tense and potentially deadly situation. Lake’s exaggerations may have created a legend, but in many ways the true story of Wyatt Earp’s life is far more interesting. He was a man of mighty achievements, but also a man with very human failings who made more than his share of mistakes. The more we learn, the more fascinating the story becomes. WW

California-based writer Casey Tefertiller is the author of Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend. For this article, which appeared in the October 2017 issue, the Wild West History Association awarded Tefertiller its Six-Shooter Award for best article in a general Western publication. Texan Bob Cash has intensively researched Earp and contributed his insights to this article. Also suggested for further reading are Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend, by Gary Roberts; The Unwashed Crowd, by Lynn R. Bailey; and Murder in Tombstone: The Forgotten Trial of Wyatt Earp, by Steven Lubet.