From June 1940 to November 1942 the air forces of Italy and Germany—the Regia Aeronautica and Luftwaffe, respectively—repeatedly bombed Allied forces on the strategically important island of Malta, south of Sicily in the central Mediterranean, while Axis ships sought to choke off Allied shipping to the British colony. The ultimate aim was to either bomb Malta’s defenders into submission or weaken their defenses in preparation for an amphibious invasion. The Allies fought heroically (and, ultimately, successfully) to prevent an Axis takeover. But the cost in lives and materiel was great.

Just after midnight on June 16, 1942, the Polish destroyer escort ORP Kujawiak (L-72) hit a mine while conducting a rescue operation near the port of Valetta, the Maltese capital. Despite valiant damage-control efforts, the crew was unable to close up the huge hole blown through the ship’s port side, and the warship sank to the bottom of the sea. There the vessel would lie undisturbed for decades. More than 70 years would pass before the wartime story of Kujawiak came to light.

In the winter of 2014 professional scuba diver and history enthusiast Peter Wytykowski attended a workshop in Toledo, Ohio. There he met Chris Kraska, whose father, Jan Kraska, was aboard Kujawiak the night the ship sank. Fascinated by the younger Kraska’s account of his father’s service in the Polish navy and the tragic events of the ship’s sinking, Wytykowski resolved to locate the shipwreck. He enlisted the assistance of Timmy Gambin, a professor of maritime archaeology at the University of Malta, and the hunt for L-72 began.

Stung by the September 1939 Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland and defeat of the Polish army, defiant Poles contributed to the Allied war effort through the end of World War II. Polish officials formed a government in exile—first in France and then in Britain—and Polish soldiers, airmen and sailors participated in numerous campaigns, notably the Battles of France and Britain in 1940, the Siege of Tobruk in 1941, and Operations Overlord and Market Garden and the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1944.

In cooperation with the British Royal Navy, the Polish navy helped escort Allied convoys—especially oil tankers and cargo freighters—in the Atlantic Ocean and the North and Mediterranean seas. Among other accomplishments, Polish destroyers engaged enemy submarines and aircraft, deployed depth charges and smoke screens, and rescued survivors from stricken vessels.

Kujawiak was among the warships assigned to escort duty. A British Type II Hunt-class destroyer escort launched in October 1940 as HMS Oakley, the 279-foot-10-inch, 1,050-ton vessel was transferred to the Polish navy before its completion. Though smaller and less heavily armed than many wartime counterparts, the ship was adapted to take on more depth charges to defend merchant ships from enemy submarines.

In May 1942 Kujawiak was dispatched to the Mediterranean to escort an Allied convoy carrying supplies to Malta. It was perilous duty, as at the time the island was the only Allied air and naval base between the British bases of Gibraltar, in the eastern Mediterranean, and Alexandria, Egypt. Malta thus became a prime target for Axis forces, and between 1940 and 1942 the 122-square-mile island group gained dubious distinction as one of the most heavily bombed places in the world.

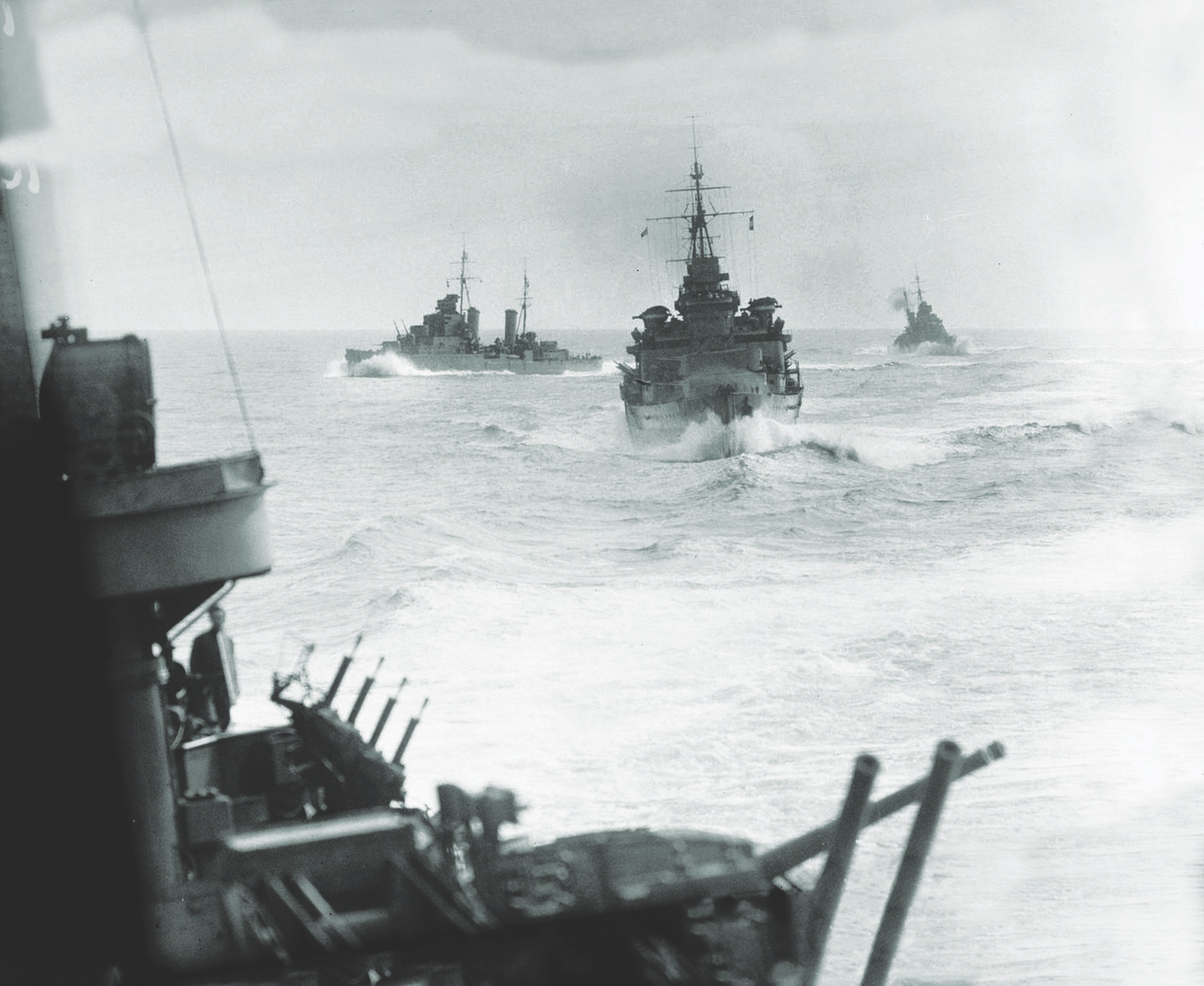

By mid-1942 the situation in Malta had become especially dangerous, as Axis aircraft had mounted raids against the island on all but one day of the first six months of the year. That June the Allies planned to send two large convoys of supplies to Malta—one westbound from Alexandria (code-named Vigorous), the other eastbound from Gibraltar (code-named Harpoon), hoping to split enemy forces mustered in opposition. The latter convoy initially comprised five supply ships and 10 destroyers that sailed from Britain to Gibraltar. On arrival in Gibraltar the convoy was joined by a tanker and two escorting corvettes, as well as Capt. Cecil Hardy’s Team X—an anti-aircraft cruiser, five fleet destroyers, four smaller destroyer escorts, and four fleet minesweepers. One of the destroyer escorts was Kujawiak. Further bolstering the convoy’s defenses was Force W, under Vice Adm. Alban Curteis, comprising the battleship HMS Malaya, two aircraft carriers, three light cruisers and eight destroyers. Closer to their destination, spread out in line between Sardinia and Sicily, four British submarines would provide overwatch.

Enemy aircraft and warships detected the convoy soon after it departed Gibraltar on June 12. German aircraft spotted the ships as they steamed south of Spain’s Balearic Islands, while more than a dozen Italian submarines were patrolling the waters north of Algeria and along the approach to Malta. The initial attacks came early on June 14, when two of the Italian submarines launched torpedoes at the convoy. Neither scored a hit. Around 10:30 a.m. aircraft from the Allied carriers beat back an enemy air raid, but an hour later Italian torpedo-bombers conducted a larger raid, sinking one cargo ship and damaging the light cruiser HMS Liverpool, which was towed back to Gibraltar. Anti-aircraft gunners aboard the defending ships managed to down two Italian planes. The next morning, in battle with Axis aircraft and an Italian navy squadron, the Allies lost three more cargo ships and the destroyer HMS Bedouin. The Italians captured 213 survivors from the British warship’s 241-man crew.

On the evening of June 15 the battered convoy finally rounded the southeastern shore of Malta and was nearing Valetta. However, due to communication lapses during its approach to Grand Harbour, the convoy strayed into a minefield. Just after midnight the destroyer HMS Badsworth hit a mine and began to founder. Kujawiak attempted a rescue operation, only to strike a mine itself just 13 minutes later. Proudly flying the red-and-white flag of the Polish navy to the end, the warship listed to port and soon slipped beneath the waves, 13 crewmen entombed within its hull. The destroyer HMS Blankney braved the minefield to pick up survivors. Of the six merchant ships in the convoy only two reached port safely.

In the aftermath of Kujawiak’s sinking its commander, Capt. Ludwik Lichodziejewski, wrote a report that included the warship’s last known position. Several postwar expeditions used his coordinates in efforts to locate the wreck, but to no avail. Kujawiak had gone missing.

Determined to solve the mystery, Wytykowski organized a research trip to the British National Archives in Kew to study all documents related to Operation Harpoon. He and his team also tracked down relevant documents from several other military archives, including the Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv in Freiberg, Germany. Analysis of those documents in turn led to the discovery of ship reports from Badsworth and Blankney. The research team used the reported positions of both vessels during the rescue operation to triangulate the location of the Polish destroyer.

After obtaining the necessary permits from Maltese authorities, project co-directors Wytykowski and Gambin launched their first expedition in September 2014. They plotted a concentrated search grid of approximately 1.5 square miles some 5 miles northeast off the coast of Valletta. After four days of searching (and a lost day due to bad weather), sonar picked up an object of a similar length and shape to a Hunt-class destroyer. It lay on its port side at 325 feet, its bow pointing south.

The search team then deployed a remotely operated underwater vehicle equipped with video cameras to get a closer look at the submerged object. Detailed analysis of the footage and comparison with technical blueprints of Kujawiak revealed the object was indeed the wreck of a Hunt-class destroyer escort. The ROV captured additional video footage and still images over the next few days, including close-ups of one of the vessel’s QF 4-inch Mk XVI twin gun mounts. That and the historical data confirmed the wreck as that of Kujawiak. It had come to rest just 1 mile north of the position given in Capt. Lichodziejewski’s after-action report.

Having established Kujawiak’s identity and location, Wytykowski and Gambin planned a 2015 expedition to explore the wreck and commemorate the sailors who lost their lives. Preparations took almost a year, during which time team members searched for relatives of the ship’s crew. They managed to track down several, including Patricia Olsztyn, sister-in-law of Ordinary Seaman Edward Olsztyn, among the 13 fallen crewmen.

The researchers also set out to locate survivors, though as seven decades had passed since the event, they knew any former Kujawiak sailors would be more than 90 years old. They managed to find just one—Leading Seaman Kazimierz Stefankiewicz, who had changed his name to Kenneth Stevens and settled in Nottingham, England. (On Aug. 19, 2017, the aging seaman turned 100 years old, and just five days after his birthday Stevens was awarded the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Rebirth of Poland for extraordinary and distinguished service to his home country.)

Throughout the follow-up expedition the team made a concerted effort to honor the fallen. The day before the team began diving on the wreck, members attended a Holy Mass in Lodz, Poland, in memory of those who’d gone down with the ship. On the final day Wytykowski and U.S. Air Force veteran Mark “Sharky” Alexander placed a bronze plaque on the wreck to commemorate the lost 13:

POLISH ESCORT DESTROYER

ORP KUJAWIAK

DISCOVERED ON SEPTEMBER 22, 2014

BY THE POLISH EXPEDITION “THE HUNT FOR L-72”

GRAVE OF THE THIRTEEN POLISH NAVY SAILORS

WHO LOST THEIR LIVES ON JUNE 16, 1942

MAY THEY REST IN PEACE

As a further testament to the fallen, the team organized a commemorative ceremony in the 17th century Upper Barrakka Gardens in Valletta. Transported to the wreck site beforehand by a patrol boat, Maltese and Polish officials and Polish veterans dropped memorial wreaths and bouquets of flowers into the sea. At the ceremony in the gardens officials unveiled a marble plaque commemorating the lost, and gunners fired a salute of 13 cannon salvos in their memory.

The exploration of Kujawiak by divers took place over three seasons in 2015, 2016 and 2017. Before beginning operations, the team tied a line to the wreck to ensure divers’ safety during decompression, which can last beyond three hours after just 30 minutes dive time below 300 feet. The divers split into three groups: Two were assigned to wreck exploration, one to supporting the deep divers.

The aim of the June 2015 expedition was to assess the condition of the wreck and take extensive photographs, as well as to place the commemorative plaque. Despite having been underwater for more than seven decades, the ship was well preserved, its hull largely intact and main features clearly recognizable. The bow was in pristine condition, the forward twin gun turret undamaged. In the command station atop the bridge the divers were able to make out the range finder, compass, pelorus (a reference tool also known as a “dumb compass”) and a chart table. The ship’s stern was in far worse condition, as it had buckled when Kujawiak slammed into the bottom. The seafloor around the stern was littered with items torn from their deck fittings, including one of the warship’s quadruple-barrel 40 mm anti-aircraft mounts.

The divers also encountered something of a mystery: The ship’s bell was not where it should have been—amidships on the starboard side near the funnel. The team feared it may have separated from Kujawiak when the destroyer escort hit the mine; if so, that meaningful artifact might be lost forever.

Finding the bell became a prime mission during the third expedition, in June 2016. Unfortunately, bad weather and strong currents limited the team to just three dives over the course of two weeks. The divers could spend only 25 minutes on the wreck, followed by hours of decompression, which left them completely exhausted on reaching the surface. The search seemed a hopeless task until the last moments of the final dive, when Wytykowski and Alexander took a closer look at the ship’s mast, which lay in pieces on the seabed. Much to their amazement, they found the bell, still attached to the mast, though wreathed in thick concretion and barely visible beneath a collapsed deck locker.

During the final dive season, in May 2017, divers focused on retrieving the bell. The team also planned to film and photograph the wreck in order to create a 3-D reconstruction—a huge undertaking, given their limited bottom time. Nevertheless, by the seventh and final dive they had completed the survey from bow to stern, including the rudder and propellers.

As for the bell, the divers first faced the arduous task of cutting through the solid steel bracket (about 1.5 inches in diameter) that attached the bell to the ship’s mast. It took them two dives. That accomplished, they secured the bell to a flotation device that when inflated was to have carried the bell to the surface. The bell proved too heavy, so the divers secured three additional personal decompression buoys to the flotation device. This time it worked, and when the bell reached the surface, team members carefully hoisted it onto the dive boat and placed it in a container filled with seawater and covered with a wet towel to protect it from oxidation in the air.

The team handed over the bell to Heritage Malta, the national oversight agency for museums, conservation and cultural heritage. Objects retrieved from saltwater must undergo extensive conservation methods to prevent further corrosion and deterioration. Over several months conservators meticulously cleaned the bell using an innovative surface-heating method. That process revealed the inscription HMS Oakley 1941—a surprising finding, given that British ships handed over to the Poles during World War II had their bells changed to reflect the vessel’s Polish name. As Kujawiak was transferred at the peak of the war, there was likely little time or impetus to change the inscription or replace the bell.

Divers capped off the final expedition by finishing their survey of the wreck. Having located and documented all features noted on the prior expeditions, they were able to determine whether Kujawiak had suffered any further degradation. Unfortunately, the wreck was visibly deteriorating and will, of course, continue to degrade.

Regardless of its inevitable decline, Kujawiak is a war grave that deserves our respect and protection. The Polish and Maltese governments have agreed to protect the wreckage, and Malta’s Superintendence of Cultural Heritage has declared the site an “area of archaeological importance” with a protective buffer zone of 1,500 feet.

The discovery of the wreck has shed new light on the intrepid Polish sailors who fought alongside the Allies in World War II. More important, after more than seven decades the 13 crewmen who lost their lives on Kujawiak have at last been recognized for their heroic actions. MH

Timmy Gambin is professor of maritime archaeology at the University of Malta and leads Heritage Malta’s Underwater Cultural Heritage Unit. Lucy Woods is a U.K.–based travel and archaeology journalist specializing in maritime archaeology and the preservation of cultural heritage. The authors would like to thank the Polish Shipwreck Expeditions Association for their important work and unwavering support on the Kujawiak project.