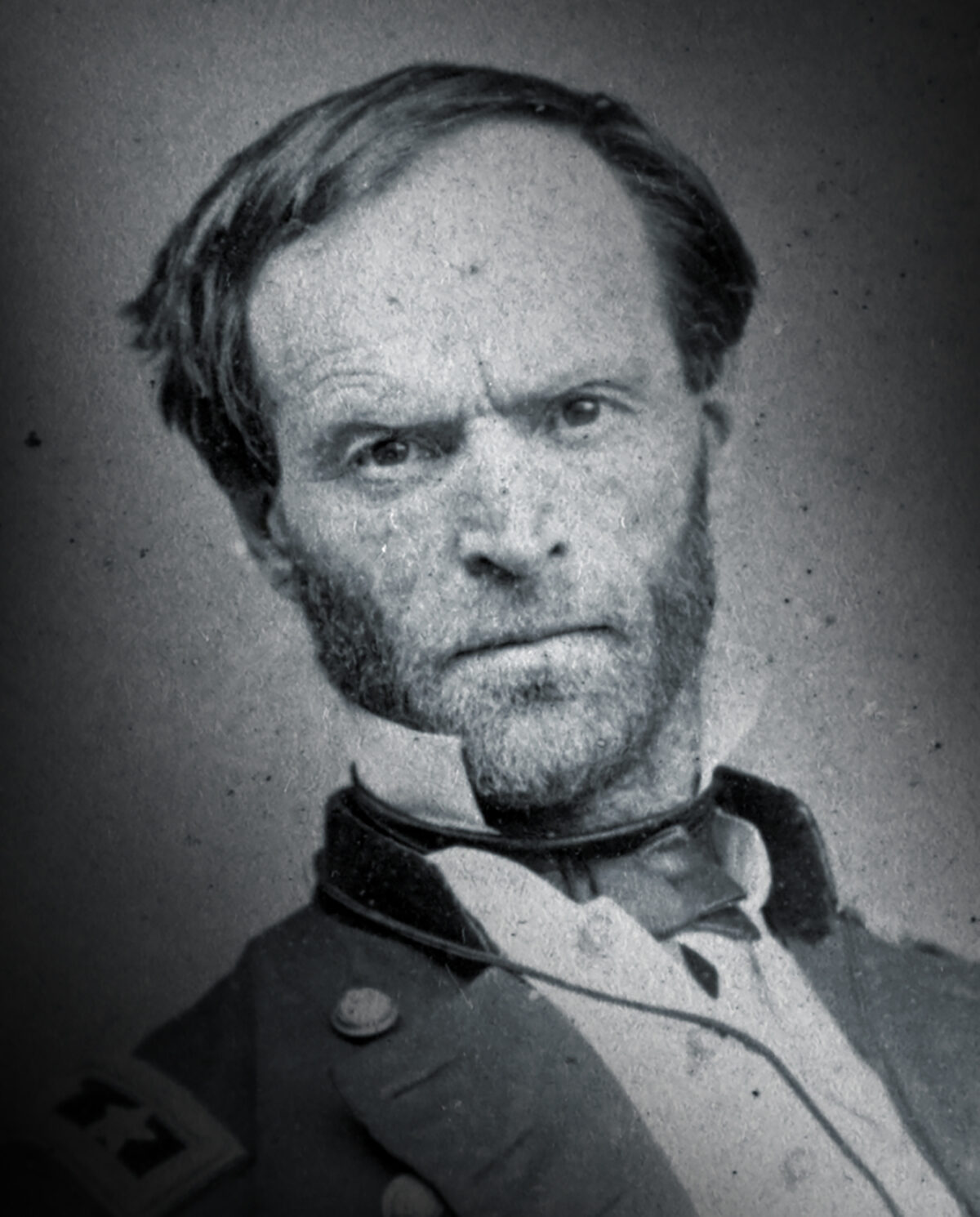

Most Americans have heard the phrase “40 acres and a mule.” Few, however, know it originated in a directive known as Special Field Orders, No. 15 (SFO 15), issued by Union major general William T. Sherman on January 16, 1865. And fewer still know the story behind the order.

SFO 15 set aside a swath of coastal land stretching 30 miles inland and extending from the St. John’s River in Florida north to Charleston, South Carolina, “for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war” and by the Emancipation Proclamation. Tis district would be entirely free of white habitation and would be “subject only to the United States military authority and the acts of Congress.” SFO 15 outlined the process whereby African American heads of families could claim up to 40 acres of land in the district. It made no mention of mules or any other livestock, but when it was implemented, a number of black families received surplus army mules; hence the expression “40 acres and a mule.”

the order came from Sherman’s headquarters, it sounds as if Sherman was an advocate of the freed slaves. Hardly. Sherman had scant sympathy for freed people. He resisted the enlistment of black soldiers and refused to use any African American regiments in his field armies. Most Union generals, to be sure, were every bit as racist as Sherman. Consequently, the military policies they created to handle the great number of slaves that fed to the Union armies tended to be highly conservative. In the occupied South, freed slaves seldom received the right to work without white supervision. Thousands found themselves confined to so-called contraband camps, a term derived from an earlier wartime theory that slaves remained property and as enemy property could be confiscated as “contraband of war.” Within these camps, freed people worked under military oversight.

In the Mississippi River Valley, the Union army forced tens of thousands of freed people into “contract labor” relationships, which dictated that, although they were technically employees and no longer slaves, they must “labor faithfully” for their employers—usually their erstwhile masters—in exchange for wages or a share of the crop. Because Sherman had military jurisdiction over practically the whole region between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River, his policies had more impact than any other Union commander.

He was also, by the end of 1864, among the most successful of Union commanders. In September 1864 he had captured Atlanta. In mid-November he had taken 60,000 troops on a 250-mile “March to the Sea,” capturing the port of Savannah five weeks later. There he paused to resupply his army and prepare his next move, a march north through the Carolinas to link up with the armies under Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, then besieging Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s army at Petersburg, Virginia.

If Sherman thought his victories would leave him free from the critical scrutiny of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, however, he was mistaken. Soon after the form of a letter from the Union chief of staff, Major General Henry Halleck, a friend of Sherman and, like Sherman, no particular friend of African Americans. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., and observant of the city’s every political current, Halleck alerted Sherman to impending trouble. “While almost everyone is praising your great march through Georgia and the capture of Savannah,” he wrote, “there is a certain class, having now great influence with the President… who are decidedly disposed to make a point against you. I mean in regard to ‘inevitable Sambo.’ They say that you have manifested an almost criminal dislike to the negro,” Halleck warned, “and that you are not willing to carry out the wishes of the Government in regard to him, but repulse him with contempt! They say you might have brought with you to Savannah more than fifty thousand, thus stripping Georgia of that number of laborers and opening a road by which as many more could have escaped from their masters; but that, instead of this, you drove them from your ranks, prevented them from following you by cutting the [pontoon] bridges in your rear, and thus caused the massacre of large numbers by [Confederate] cavalry.” Halleck urged Sherman, for his own good, to do something positive for the freed slaves, something that would allay the suspicions of his masters in Washington.

Sherman did no such thing. On January 11, however, Stanton arrived in Savannah aboard a revenue cutter, accompanied by two high-ranking officers and a number of civilians, and went straightaway to visit Sherman at his well-appointed headquarters in the home of a prosperous local merchant. Almost at once he interrogated Sherman on the matter of the cutting of his pontoon bridges and the abandonment of black refugees to the mercy of pursuing Confederate horsemen. Sherman summoned the corps commander on whose watch that had occurred. Together they offered Stanton an explanation of what had transpired that, according to Sherman, satisfied the concerns of the secretary of war.

But either then or the next day, Stanton informed Sherman that he and Sherman would meet with 20 local African American clergy and lay leaders. At 8 p.m. on January 12 the group assembled at Sherman’s headquarters. The oldest was 72 years old, the youngest 26. Fifteen had been slaves. Some of these had been freed by their masters or had purchased their freedom; about half were liberated only with the arrival of Union troops. To speak on their behalf, they chose 67-year old Garrison Frazier, a Baptist minister who had preached the gospel as both a slave and a free man.

Stanton put 12 questions to Frazier, each intended, it would seem, to impress upon Sherman the loyalty of the freed people, their intelligence, and their understanding of the stakes of the war and the meaning of freedom. A Union officer took down a verbatim record of the questions and responses. The third question was key: “State in what manner you think you can take care of yourselves, and how can you best assist the Government in maintaining your freedom.”

“The way we can best take care of ourselves,” Frazier replied, “is to have land, and turn it and till it by our labor—that is, by the labor of the women, and children, and old men—and we can soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare; and to assist the Government the young men should enlist in the service of the Government, and serve in such manner as they may be wanted.…We want to be placed on land until we are able to buy it and make it our own.” Asked whether he thought the freed people would prefer to live by themselves or in the company of whites, Frazier replied, “I would prefer to live by ourselves, for there is a prejudice against us in the South that will take years to get over.” All but one of the other African Americans present agreed.

Finally, before posing the 12th and final question, Stanton asked Sherman to leave the room. Ten he asked Frazier to tell him about “the feeling of the colored people toward General Sherman.” Although this clearly invited Frazier to criticize Sherman, Frazier refused to take the bait. “We have confidence in General Sherman, and think what concerns us could not be under better hands.”

Frazier’s judicious response would hardly have mollified Sherman. He was outraged that Stanton would question the African Americans behind his back, and nothing that transpired that evening changed his opinion of the freed people, which remained precisely as he had expressed it earlier in the day in a letter to Halleck. “The n——? Why in God’s name can’t sensible men let him alone?” Rejecting any special projects on behalf of the freed people, he had fumed, “Don’t military success imply the safety of Sambo and vice versa?”

After the interview, however, Stanton asked Sherman to issue a directive granting freed people lands along the coastal strip. Stanton reviewed and approved a draft of SFO 15, which Sherman issued the day after Stanton left Savannah. Two weeks later Sherman embarked upon his march through the Carolinas; by that time hundreds of freed people were migrating toward the coastal district. By war’s end about 20,000 occupied the abandoned land; an additional 20,000 arrived in the months that followed.

Their tenure was short-lived. Nearly all the land had belonged to white planters who fed into the interior with the advent of “Lucifer’s legions.” After the war most of the planters claimed the right to return to their property. Conservative president Andrew Johnson thoroughly sympathized with them. Thus, by 1867 most of the freed people had been ejected from the 40 acres given them under SFO 15. Sherman, who had never believed in the order issued under his authority, said not a word in protest.