High above the Arizona desert in 2004 a harrowing scene played out. Lieutenant Colonel Edward B. Lamar Jr., a veteran air tanker pilot with service in Bosnia and Iraq, was flying a KC-135 on a training mission, refueling a flight of four A-10 Thunderbolts, when one of the Warthogs got stuck on his boom. “We can’t bail out because we’ll hit his airplane,” Lamar recalled. “He can’t punch out because we’ll crash. We can’t land together. Any other plane, it wouldn’t have been as bad, but with the A-10 the boom’s right in front of the cockpit.”

The tanker crew and Warthog pilot struggled for what seemed like an eternity to separate the aircraft, eventually arriving at a solution. “The guy wound up killing both his generators at the same time we retracted the boom,” said Lamar, “and it somehow interrupted the electrical charge of the jaws that were keeping him clamped onto us. Finally—after 45 long minutes—he managed to break free. It damaged the boom and the fueling receptacle, but we both landed safely.”

Fortunately, episodes like this have been rare in the 85-year history of in-flight refueling, or IFR. That’s a good thing, because aerial refueling has never been as important as it is today, especially with air forces operating in hostile airspace such as over Iraq and Afghanistan. The aerial ballet that is modern IFR remains a key component in warfare and reconnaissance, as well as humanitarian missions.

It all started with a barnstorming stunt in November 1921, when wing-walker Wesley May strapped a gas can to his back and stepped out of an airborne Lincoln Standard, crossed over to a Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” and filled its tank. The idea had actually been envisioned during World War I—notably by Russian aviator Alexander de Seversky in 1917—but it didn’t get serious consideration until the 1920s, when record-breaking endurance flights began to make headlines.

In June 1923 the crews of two U.S. Army Air Service de Havilland D.H.4Bs accomplished the first practical IFR, using a hose to transfer 75 gallons of gas between the planes. A more dramatic experiment took place in the first week of January 1929, this time with a Fokker C-2A trimotor crewed by Major Carl Spaatz, Captain Ira Eaker, Lieutenant Harry Halverson, Lieutenant Elwood Quesada and Sergeant Ray Hooe. Since no one knew how long the Fokker could stay aloft without landing, it was dubbed Question Mark. The answer was just under 151 hours, with 42 successful refueling sorties made by two Douglas C-1s acting as tankers. One fuel transfer actually took place over the Rose Bowl in Pasadena while Georgia Tech and California battled it out on the field below. The flight finally ended after the Fokker developed engine trouble. One of the Douglas pilots, Captain Ross Hoyt, later achieved legendary status thanks to the Brig. Gen. Ross Hoyt Award, which is awarded annually to the Air Force’s top refueling crew.

In a 1935 demonstration, brothers Fred and Al Key made use of the first spill-free refueling nozzle, employing a cutoff valve designed by A.D. Hunter. That device has been essential to IFR ever since.

Despite these preliminary successes, the U.S. Army Air Corps did not zealously pursue aerial refueling in the run-up to World War II. At one point the U.S. Navy considered developing the strategy for its seaplanes, but once aircraft carriers came on the scene, IFR took a back seat. The concept was actively explored by other nations, however, with Britain taking the lead.

The Royal Air Force’s early test programs involved joining two aircraft together with trailing lead lines, after which a crewman on the receiving plane dragged the refueling hose to the fill receptacle using brute force. The British later perfected that technique. In fact, the first private enterprise dedicated to aerial refueling, Flight Refuelling Limited, was started in 1934 by renowned British aviator Sir Alan Cobham, whose company developed equipment that has long supplied tankers with hoses and “probe-and-drogue” receptacle systems.

Part of FRL’s development work focused on commercial aviation, envisioning a future in which transatlantic and other long-distance routes became a matter of routine. But although experiments done toward that end, such as one performed in 1929 along a U.S. transcontinental mail route, were on the whole successful, they never attracted customers. Commercial pilots were not enthusiastic about IFR, and it was thought passengers would be even less so.

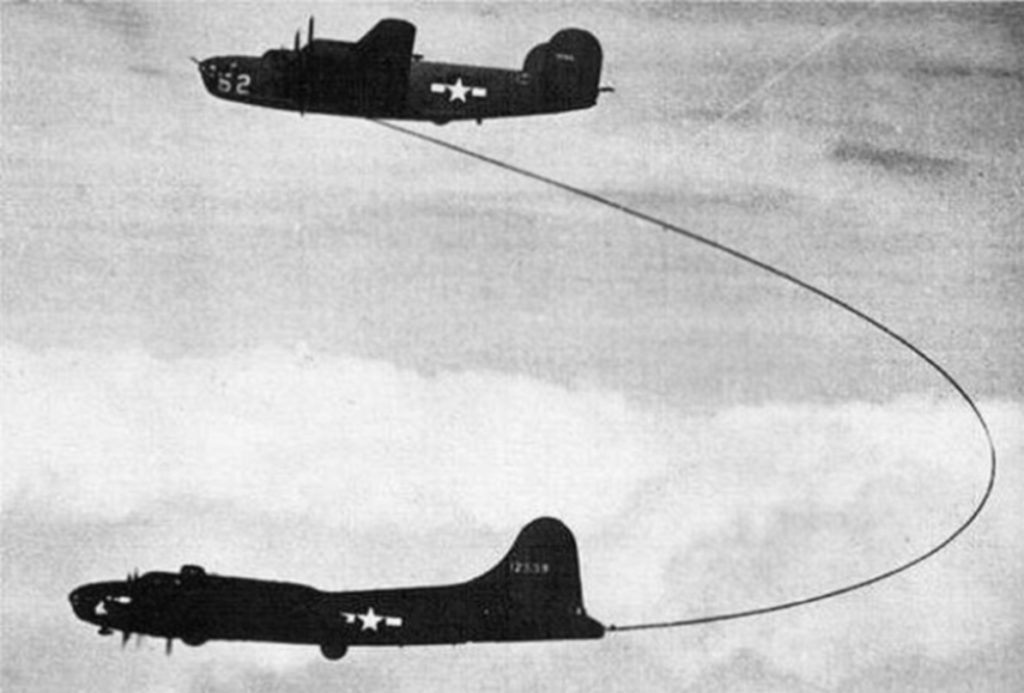

The Allies conducted successful air-to-air tests during WWII, including one in which a Consolidated B-24 refueled a Boeing B-17. But the Luftwaffe’s defeat in the Battle of Britain, coupled with Allied successes in North Africa and Italy, ensured that American aircraft would not be forced to fly grueling transatlantic missions. In the Pacific, the introduction of the long-range Boeing B-29 and North American P-51 meant that bombers and their escorts could reach Japanese targets and return to base without the need for IFR.

Following WWII, the Communist threat that fostered the Cold War made IFR a growing American priority. The mission for Strategic Air Command, formed in 1946, became preparation and visibility, and refueling was an integral part of both. In 1948 the U.S. Air Force purchased two sets of Cobham’s IFR hardware, manufacturing rights to FRL’s system, a contract for 40 additional sets and a year of technical support. The first IFR squadrons were established at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and Roswell Air Force Base in 1948, at a time when Lt. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay was launching operations to showcase the strength of America’s strategic bomber force.

This new emphasis on strategic bombing produced the first dedicated air tanker, the KB-29M, a modified B-29 Superfortress. When operations commenced with the KB-29 and KB-50 (a tanker developed from the B-50 design update of the B-29), they relied on the reel hose and drogue method developed by the U.S. subsidiary of FRL. The drogue was an aerodynamically designed basket that the probe of the receiver aircraft locked into during the refueling process. But the system had its problems: Hooking up with the tanker was tricky for pilots, the pumping process was slow and crewmen found it difficult to keep the fuel-laden hose stable during fueling. Despite these difficulties, the exigencies of the Cold War demanded IFR capability, and the probe-and-drogue method worked. Some KB-29 and KB-50 refuelers were equipped with wingtip hose reels in addition to the standard fuselage assembly, enabling simultaneous refueling of three fighters or other smaller aircraft.

By the late 1940s, however, SAC was looking for a way to transfer more fuel faster to accommodate its new fleet of gas-guzzling jets. After approaching Boeing, SAC vacillated on the project, but Boeing continued working on the problem. Its research department started looking into possible configurations for a “flying boom,” a telescoping aluminum tube extending from the tanker. The name is appropriate because the boom operator controls the flying boom’s azimuth and elevation with a dual-wing “ruddervator” on the boom shaft. One of the ideas called for the boom to telescope upward from a B-29 forward gunner’s position, with the tanker trailing the receiver aircraft. Ultimately aerodynamics, safety and efficiency prompted designers to have the boom extend from the lower rear fuselage of the tanker toward the nose of a receiver plane, flying behind and below.

In May 1949, U.S. Air Force Air Materiel Command issued Boeing a contract for the flying boom, to be installed in KB-29Ps. The system featured a flow pump capable of transferring fuel at the rate of 700 gallons per minute. SAC made it mandatory for all its new aircraft to be fitted with receptacles to accommodate the new equipment, but Tactical Air Command (TAC) continued to order fighters equipped with probes. Eventually a detachable hose and drogue was developed that could be added onto the flying boom, allowing tankers to refuel a wide variety of thirsty planes.

The KB-29 and KB-50 were soon outdated, however, since the prop-driven tankers lacked sufficient speed to easily refuel jets. Although some KB-50s eventually mounted auxiliary General Electric J-47 engines to increase their speed, their active service days were numbered.

The next generation of dedicated tankers was developed in tandem with the new medium-range bomber that would become the centerpiece of SAC strength for more than a decade: the Boeing B-47 Stratojet. The B-47’s range, heavy payload and fuel requirements meant that IFR would be more important than ever. In response Boeing developed the KC-97 Stratotanker, an adaptation of the four-engine, prop-driven C-97 Stratofreighter. Both planes began their service life late in 1950 in training missions with the 306th Bombardment Wing. The Air Force ordered far more KC-97 tankers (Boeing produced 816 in all) than C-97 transports. Still, the piston-engine KC-97 needed to make a shallow dive to gain sufficient speed to refuel the B-47, which had to fly nose-up throughout the process. The introduction of the KC-97L, with a supplemental jet engine mounted under each wing, gave the tanker the speed required to refuel jet bombers without descending.

The Korean War saw the first tactical use of in-flight fueling for recon and fighter-bomber operations. In July 1951, a KB-29M refueled four Lockheed F-80s over North Korea—the first IFR over enemy territory. The first combat aerial refueling took place on May 29, 1952, during a bombing mission by 12 Republic F-84E Thunderjets from Japan, targeting Sariwon, North Korea. And that September Lt. Col. Harry W. Dorris, flying an F-80 with a 265-gallon fuel tank on each wingtip, pushed the endurance envelope for pilot and aircraft during one marathon mission: He bombed, launched rocket attacks, strafed and did reconnaissance over the course of a sortie that lasted 14 hours and 15 minutes—refueling three times before landing.

Following the Korean War, the Hungarian and Suez Canal crises prompted continuation of training exercises and rotations begun earlier in the 1950s, when SAC transferred bomber and fighter wings en masse to forward locations. Many of those transfers involved IFR.

Meanwhile, U.S. Navy refueling shifted from the experimental to the operational phase, still relying on the probe-and-drogue method. Navy and Marine Corps aircraft continue to use this method today.

Though it served the B-47 and subsonic jet wings well, the KC-97 was ultimately destined to be replaced once the next-generation bomber, the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, arrived. The reason? The B-52 had to cruise at near stall speed when refueling from the KC-97. Furthermore, the KC-97 could offload only 53,000 pounds of fuel, 21 percent of the B-52’s capacity, and the bomber burned a great deal of fuel descending to and climbing back from the KC-97’s altitude.

The B-52’s introduction led to the development of the most versatile tanker ever built—Boeing’s KC-135, which became the mainstay of the Air Force refueling fleet and still remains in service. Realizing that the Air Force would need a jet-powered tanker to complement its jet bombers, Boeing had begun work on the 367-80 prototype in 1952. The sweptwing 367-80—better known as the “Dash-80”—would become the first American-manufactured commercial jetliner, the 707/720 series, but it also yielded cargo and specialized use aircraft for the military. The KC-135A, featuring four of the new Pratt & Whitney J-57 engines and equipped with a flying boom, first flew on August 31, 1956. It carried 31,200 gallons of fuel, a tremendous improvement over the KC-97’s capacity of 8,513 gallons. Additionally, refueling could take place at 35,000 feet, almost twice the altitude of the KC-97. With a jet-powered tanker, bombers no longer had to slow down and decrease altitude to take on fuel.

SAC’s needs during the first two decades of the Cold War resulted in a number of changes in operational readiness for the bomber wings. First came the one-third ground alert posture, in which a third of the SAC bomber fleet needed to be prepared to be airborne within 15 minutes. The 1958 crises in Lebanon and Taiwan contributed to SAC’s decision to commence airborne alert posture in the last months of that year, and to disperse planes to keep them from being destroyed in a major strike on a single airfield. The changes put enormous strain on air-to-air refueling squadrons and wings. At the same time, SAC conducted speed and endurance tests with IFR to demonstrate the strike capabilities of its bombers, particularly B-52s.

The Cuban Missile Crisis, from October 14-28, 1962, posed the greatest challenge yet to SAC, and tankers proved crucial throughout that watershed event. B-47 bombers were dispersed to select military and civilian airfields. RB-47 and KC-97 tankers joined Lockheed U-2 spy planes and other aircraft in the search for Soviet ships headed to Cuba with missiles and support equipment.

A few years later, spy flights by the fastest jet ever made, the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird, also involved Air Force KC-135 tankers. For those operations, however, specially designated KC-135Q tankers had to carry two types of fuel—their own and the unique jet fuel used by the SR-71. The use of a hydrogen peroxide supplement that is denser than jet fuel reduced the amount of JP-7 carried, but it allowed the KC-135Q to pump 147,000 pounds of fuel into the Blackbird in 11 minutes—a record 1,200 gallons per minute.

The Vietnam War brought IFR to the forefront, as it played a huge role in strategic, tactical, air mobility and recon operations. Early in the war, between 1964 and 1966, tankers helped to get fighter and bomber wings to Southeast Asia bases. Most of the tankers stationed in-country were SAC KC-135s that serviced fighters and recon aircraft. Refueling circuits were set up in northern Thailand and the Gulf of Tonkin, with a few in South Vietnam, and TAC control squadrons directed thirsty aircraft to airborne tankers at “anchors.” Pilots would routinely ask KC-135 crews if they were a “mama” (hose-and-drogue capable) or “papa” (flying boom only). A drogue adapter could be added to tankers, but only when they were on the ground.

There are plenty of stories about tankers refueling groups of four or more aircraft at a time in Vietnam, as well as many accounts of individual bravery by refueling crews. Staff Sgt. Michael P. Schmitz, a radar operator in the 621st TAC Control Squadron at Nakhon Phanom, Thailand, remembered one mission in 1968 when his tanker actually towed a shot-up Republic F-105 Thunderchief back to base via its boom. “We were turning the tanker to roll out in front of him when the F-105 pilot called that he had a flame-out,” Schmitz recalled. “Instead of doing a normal 15-degree angle bank, the tanker put it down to a 30-degree bank, lowered its nose and rushed in front of the fighter, so the boom operator could hook him up. They dragged him back into Thailand and dropped him off at the nearest base.” The tanker crewmen received commendations for their extraordinary efforts.

There could be no doubt about aerial refueling’s importance to aviators in Vietnam: In the course of just one year, 1966, KC-135 crews were credited with saving 53 planes and crews that otherwise would have been lost. Tankers were always on the alert for downed pilots and other emergencies, and frequently performed IFR during search-and-rescue missions.

Even after America’s involvement in Vietnam ended, escalating Cold War operations and Middle East tensions resulted in the need for SAC to continue to upgrade its assets. After studying aircraft developed for the new wide-body commercial fleets—the Boeing 747, Lockheed L-1011, McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and Lockheed C-5 cargo plane—the Air Force decided on the DC-10, contracting with McDonnell Douglas to produce 60 planes at a conversion cost of $88 million each.

The first of the KC-10 Extenders was delivered on March 17, 1981. With a full load of fuel, the KC-10 has the greatest range of any production aircraft in the world, and it can refuel planes using both the flying boom and hose-and-drogue methods.

Despite the introduction of the KC-10, the KC-135 still made up the bulk of U.S. Air Force tanker assets. In 1984 a conversion program began in which the older tankers were upgraded with General Electric CFM 56 engines, reinforced wing spars and other improvements and redesignated KC-135Rs. While KC-10s primarily serve in the strategic role, refueling transports or large numbers of tactical aircraft on ferrying flights, KC-135s continue to perform most in-theater refueling.

Operation El Dorado Canyon, the 1986 bombing of Libya, was among the first conflicts in which the KC-10 saw service. Since European nations would not allow staging or overflight rights for the General Dynamics F-111s involved in that operation, all combat flights commenced in the British Isles and were refueled en route. During Operation Desert Shield in 1990, KC-10s were involved in ferrying fighters to Saudi Arabia as part of the buildup for Operation Desert Storm. More than 300 tankers—KC-10s and KC-135s—flew nearly 15,000 sorties during those operations, performing some 46,000 refuelings.

In 1993, when SAC was inactivated, tankers were assigned to Air Mobility Command. As the U.S. military has continued to respond to global challenges—in Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan, for example—IFR continues to play an integral role in strategic and tactical operations.

Former tanker pilot Edward Lamar Jr., who flew KC-135Es and Rs for 15 years, likens the decisions a tanker pilot faces on each mission to playing a hand of cards: “You’d draw cards at different steps on the way—my crew, the airplane, the weather. And what happens is guys will look at cards individually and not compare them: ‘Some auxiliary system’s not working right; it’s OK to take it. Well, the weather’s not that great there, but it’s within limits. Can you give us 10,000 extra pounds?’ Now I’ve got three bad cards. For a combat mission, you fly one set of rules—do whatever it takes to accomplish the mission and bring the airplane back, so it can accomplish the next mission. But in peacetime you want to have a bigger buffer between you and bad things happening. Each bad card you get erodes that buffer. You look at each card in isolation: ‘Oh, I can handle this, I can handle that.’ But can I handle this, this and this all at the same time? And all of a sudden that buffer is a lot less than you want it to be.”

Tanker crewmen face their own set of challenges, such as maintaining the airplane’s center of gravity as fuel flows from it. The co-pilot initiates pumping after contact is made, and the cockpit crew is responsible for maintaining even fuel distribution in the various wing and fuselage bladders. The nylon bladder walls are less than one-sixteenth of an inch thick, and interior baffles cut down on fuel movement. A series of valves controls the fuel flow. During an emergency, any member of the tanker crew, as well as the pilot of the receiver aircraft, can call for a “breakaway,” in which the boom is released and the planes immediately separate.

Retired Brig. Gen. Paul Cooper, a Lockheed C-141 Starlifter pilot, provides a perspective from the other side of the IFR equation. He recalled that refueling a “heavy” posed special challenges: “As you got about 100 feet behind the tanker you would encounter the downwash coming off the tanker wings. This acted as a wall—you had to add extra power to penetrate it and then immediately take the power off. As you came underneath the tanker, the C-141 bow wave would cause the tanker tail to rise. If the tanker pilot did not correct quickly for it, there also could be problems. Just like a large ship or heavy railroad train, it became harder to start and stop while taking on fuel, and it was even more critical to maintain position.”

In today’s U.S. Air Force, Air Combat Command is responsible for the deterrent force that maintains peace and conducts combat operations. Air Mobility Command is responsible for logistics, ambulatory services and deploying military personnel. IFR is the glue that holds all these operations together. As boom operator Chief Master Sgt. Bruce Garcia aptly summed it up, “Nobody kicks ass without tanker gas.”

California-based writer Jay Wertz wishes to thank the Public Affairs offices at March Air Reserve Base and Davis-Monthan Air Force Base for their help, as well as the Air Force personnel he interviewed. Further reading: Range Unlimited: A History of Aerial Refueling, by William G. Holder and Bill Holder; Passing Gas: The History of Inflight Refueling, by Vernon B. Byrd Jr.; and Seventy-Five Years of In-Flight Refueling, by Richard K. Smith.