Should campaigns against Native Americans and Confederates be viewed as one war or two?

During the last weeks of August 1862, Dakota Sioux warriors cut a violent swath through much of Minnesota. Far to the southeast, Union forces battled Confederates in the campaign that led to the Second Battle of Bull Run. “We are in the midst of a most terrible and exciting Indian war,” read a telegram to Abraham Lincoln from St. Paul on August 27. “A wild panic prevails in nearly one-half of the State. All are rushing to the frontier to defend the settlers.”

A week later, following defeat at Bull Run, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles recorded in his diary, “Our great army comes retreating to the banks of the Potomac, driven back to the entrenchments by rebels.” An executive order from Lincoln the previous day had directed government clerks and employees to be “armed and supplied with ammunition, for the defense of the capital.”

Should these events in Minnesota and northern Virginia both be considered part of the Civil War? More broadly, should confrontations between U.S. forces and Native Americans between 1861 and 1865 be treated as elements of a single military conflict that also witnessed conventional operations between Union and Confederate armies?

[dropcap]A[/dropcap] growing body of scholarship interprets the Civil War and military actions against Native Americans in the West as parts of one historical process. This trend exemplifies how historians, with their advantage of hindsight and access to all kinds of sources, often identify patterns by exploring seemingly disparate factors. In 2003, the distinguished Western scholar Elliott West assessed martial action against the Confederacy and against Native Americans as prongs of a single U.S. state-building effort in the 19th century. By concentrating on the war between the United States and the Confederacy, West argued, Civil War scholars had ignored a more “powerful drive toward national consolidation…the integration of a divided America into a whole.”

Other historians have seconded this viewpoint. For example, Megan Kate Nelson, writing about Apache Pass, Ariz., posited “a Civil War that was fought over African American emancipation in the East, and American Indian subjugation in the West.” Durwood Ball, an authority on the prewar army in the West, similarly stated: “By mid-1863, the Union war had become an epic struggle to terminate the shameful social injustice of Southern slavery; that same war, when waged in the West, advanced the national program to subjugate, reduce, and concentrate those Native Americans still living freely.”

It is always worth asking whether new interpretive frameworks would make sense to the historical actors who lived through an era. In this case, most people in the United States almost certainly would have found it puzzling to label military operations against Confederates and those against Indians between 1861 and 1865 as the “same war.” From their perspective, the war against the Confederacy involved the highest stakes—saving the republic, salvaging the promise of democracy in the western world, and guarding the legacy of the founding generation. That war dealt with a unique and existential menace and commanded nearly universal attention throughout the nation. Conflicts against Indians posed no mortal threat to the republic. Concerned with expanding and developing the nation’s continental empire and protecting white settlers, they continued longstanding policies and actions and largely affected only those individuals directly involved.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Political leaders, soldiers, and the press habitually treated the two arenas of warfare as distinct.[/quote]

Beyond this profound disparity in degree of threat to the nation, numbers and motivation for service help explain why the loyal population separated the two spheres of military action. The war to save the Union placed more than 2.2 million citizen-soldiers into uniform, the majority of them true volunteers, and cost billions of dollars. “What saved the Union,” noted Ulysses S. Grant admiringly in the 1870s, “was the coming forward of the young men of the nation…as they did in the time of the Revolution, giving everything to the country.” The Indian wars always had been, and going forward past Appomattox would remain, primarily the bailiwick of the tiny Regular Army. Its ranks contained men who took up arms as a profession, with no specific crisis to meet.

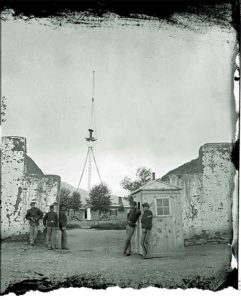

William Tecumseh Sherman, as general in chief of the U.S. Army after the war, got at the matter of scale when he wrote of infantry units deployed in Western posts: “To call the garrisons an Army is simply a misnomer. They are little squads of men strung along a frontier of fifteen hundred or sixteen hundred miles.” Such soldiers and their mission would never be equated, by the Civil War generation, with the Armies of the Potomac, the Tennessee, or the Cumberland.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t is most fruitful to interpret wartime struggles that pitted Indians against the U.S. Army and territorial military units as part of a much longer chronological trajectory. Three of the most written-about episodes involved the uprising and relocation of the Dakota Sioux from Minnesota in 1862-63, the forced resettlement of Navajos by U.S. forces under Brig. Gen. James Henry Carleton in 1863-64, and the slaughter of approximately 150 Cheyenne and Arapaho people, including many women and children, at Sand Creek, Colorado Territory, in 1864. These kinds of incidents would have occurred, at some place and in some fashion, in the absence of the four-year slaughter triggered by sectional wrangling and waged by large national armies. They fit within a framework that connects innumerable episodes from the Tidewater and Pequot wars of the 17th century to the conflicts between Native Americans and the U.S. Army during the post-Civil War decades.

Continuities across time abound. During the summer of 1863 in Cañon de Chelly, Colonel Christopher “Kit” Carson’s command destroyed crops on which Navajos “were depending entirely for subsistence” during the ensuing winter. Carson’s actions recalled attempts to deny Indians sustenance and shelter that went back to “feed fights” of the colonial era or, nearer the Civil War, to Colonel William J. Worth’s actions during the Second Seminole War in 1841-42. The relocation of the Dakota Sioux in Minnesota and, more famously, “The Long Walk” of 8,000-9,000 Navajos from modern-day Arizona to the Bosque Redondo near Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory, recalled the “removal” of the “Five Civilized Tribes,” so called in the 19th century, from the Old Southwest to what is now Oklahoma.

Wartime friction with Indians also inspired debates about methods that had arisen in earlier eras. One side, usually dominated by white voices from frontier areas, called for unrestrained war against Indians. For example, Colonel John M. Chivington, who led the Colorado and New Mexico units at Sand Creek, claimed “that to kill them is the only way we will ever have peace and quiet in Colorado.”

Others decried such brutal methods, as when Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania remarked in May 1864 “that, in nine cases out of ten, Indian wars have been produced by the provocations of the whites.” Going back to the late 18th century, insisted Stevens, overwhelmingly “the breach of faith has come from the white man….”

Political leaders, soldiers, and the press habitually treated the two arenas of warfare as distinct. Reactions to the violence in Minnesota illustrate this point. Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet, the Second Battle of Bull Run and Antietam prompted numerous discussions. But the fighting in Minnesota in August and September, which resulted in more than 500 dead white civilians and the mass hanging of 38 Indian men at Mankato later that year, received scarcely any mention. Indeed, the best-known aspect of the Minnesota drama related to Lincoln’s commuting death sentences of more than 250 Indians. Secretary of the Navy Welles devoted portions of just two entries in his voluminous diary to the Sioux uprising, both of which commented about executions.

Presidential secretary John G. Nicolay, sent by Lincoln to Minnesota, separated events there from the war against the Confederacy. In messages to Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton on August 26 and 27, he referred to the bloodshed as an “Indian war” that had wreaked havoc among settlers. “Compared with the great storm of rebellion which has darkened and overspread our whole national sky,” wrote Nicolay a few months later, “the Indian war on our northwestern frontier has been a little cloud ‘no bigger than a man’s hand.’” He went on to sketch a long historical arc unconnected to efforts to suppress the rebellion. Linking the violence in Minnesota to “similar events in our history,” Nicolay suggested that from “the days of King Philip to the time of Black Hawk, there has hardly been an outbreak so treacherous, so sudden, so bitter, and so bloody….”

Lincoln’s annual message to Congress in December 1862 aligned with Nicolay’s observations. Early in the message, he alluded to the “civil war, which has so radically changed for the moment, the occupation and habits of the American people….” Later in the text, he informed Congress that the “Territories of the United States, with unimportant exceptions, have remained undisturbed by the civil war” and also mentioned “Indian tribes upon our frontiers…[who] have engaged in open hostilities against the white settlements in their vicinity.” Lincoln referred to the fighting in Minnesota as “this Indian war,” during which “not less than eight hundred persons were killed by the Indians and a large amount of property destroyed.”

The Lincoln administration briefly considered sending paroled Union soldiers to augment local forces in Minnesota—a sure sign of separating military action against the Confederates from that against Indians. Under a cartel between the United States and the Confederacy that governed prisoners of war, paroled men could not return to service until they had been exchanged for soldiers captured by the other side. Yet Secretary Stanton, in response to a plea from Minnesota’s governor, embraced the idea of “the paroled soldiers being sent to the Indian borders” as an excellent one that “will be immediately acted upon.” Lincoln backed Stanton on September 20, urging that paroled soldiers be moved “to the seat of the Indian difficulties…with all possible dispatch.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The Lincoln administration briefly considered sending paroled union soldiers to augment local forces in Minnesota.[/quote]

Discussion of the issue continued for a month. General in Chief Henry W. Halleck sent three communications to the president on October 3-4, the last of which advised: “After full consultation with the Secretary of War and Colonel [Joseph] Holt it is concluded that the parole under the cartel does not prohibit doing service against the Indians.” The cartel, Halleck had stated in his initial reply, stipulated only that parolees not “bear arms against the Confederate States during the war or until exchanged.” Attorney General Edward Bates weighed in on October 18 with a contrary opinion: “It is the plainly declared purpose of the Cartel to prevent the use of prisoners paroled…in the discharge of any of the duties of a soldier….” Thus did four top officials, all lawyers who never would have used non-exchanged parolees to fight Confederates, seriously discuss utilizing such men in what they deemed an Indian war.

Editorial choices in Harper’s Weekly manifested a sharp distinction between the Indian war in Minnesota and operations against the Confederacy. During September, the newspaper contained multiple stories and illustrations concerning Second Bull Run and Confederate invasions of Kentucky and Maryland. Two passages totaling 15 lines covered Minnesota—one of which underscores attitudes about the relative importance of the Indian and Confederate wars. Because of escalating chaos, Governor Alexander Ramsey requested an extension to meet the state’s quota for troops in August. Harper’s Weekly printed the president’s perfunctory response: “Attend to the Indians. If the draft can not proceed, of course it will not proceed. Necessity knows no law. The Government cannot extend the time.” Lincoln’s reply signaled that the nation needed men to fight Rebels, and Ramsey could deal with Indians on his own.

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]any soldiers serving in remote Western areas nourished disappointment at being so far from what they considered the real war. Early in 1862, an Iowan affirmed that deployment in Dakota Territory “is not the height of our ambition. We are anxious to take an active part in this struggle for national existence, and distinguish ourselves…in maintaining our country’s rights and restoring peace and harmony to its now torn and distracted States.” Similarly, a member of the 4th Minnesota Infantry, a unit initially assigned to garrisons on the frontier, recalled how men in the regiment considered duty against Indians far less important than crushing the Confederacy and held out hope for a chance to help save the nation. “Our men believed that the war would be a long one,” he observed in designating the effort to defeat the Confederacy the principal conflict, “and that they would have the opportunity to see all the fighting that they would desire.”

It is difficult to imagine duty more removed from the seat of decisive military events than at many posts along the Western frontier. Typical was Fort Garland, which stood in the shadow of 14,351-foot Blanca Peak in the Sangre de Cristo range and guarded the eastern entrance to Colorado’s remote San Luis Valley. In October 1862, an inspector sent north from Santa Fe reported that 209 officers and men of the 1st New Mexico and 2nd Colorado Volunteers occupied the fort. The inspecting officer pronounced the New Mexicans “very deficient” in skirmish drills and “sadly deficient” in target practice. Officers “appeared sober but wanting in energy & industry,” and the 1st Colorado suffered from “laxity of discipline.” Moreover, the inspector found the guard duty “very negligently attended to” and the fort’s layout “scarcely defensible.” In sum, the garrison at Fort Garland, lackadaisical and without pressing business, seemingly marked time in an isolated world of its own.

Witnesses whose service spanned the Civil War and postwar years reveal how soldiers explained the transition from a war to save the Union to a war against Indians. George A. Forsyth, a volunteer who fought throughout the Civil War and held a commission in the postwar U.S. Army, addressed how quickly the change took place. “Scarcely had the echoes of the guns at Appomattox Courthouse died away,” he wrote, “when the demands of the West for protection from the warlike Indians on the great plains forced themselves upon the attention of Congress….” Only with Confederate surrender could “the urgent needs of the Western frontier, which had necessarily been neglected during the civil war, became once again one of the absorbing questions of the hour.”

Like Forsyth, George W. Baird juxtaposed the wars against Rebels and Indians. Colonel of the 32nd USCT during the Civil War and later an officer in the Regular Army, Baird spoke in 1906 before members of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. He tied the postwar Regular Army’s efforts against Indians to the professional soldiers of Arthur St. Clair and “Mad Anthony” Wayne who fought the battles of the Wabash and Fallen Timbers in the early days of the republic. Aware that MOLLUS meetings focused on the Civil War, Baird remarked that he would talk about “a war not less perilous, calling for rather more than less of heroism, than the war of the rebellion.” Giving full credit to both the “heroic little army of the frontier” and “the great national force of the period this order commemorates,” Baird lamented that the former “had no Homer to celebrate them in immortal verse.”

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]ongressional handling of veterans’ benefits showcased how Indian wars stood apart from the nation’s four-year effort to defeat the Rebels. Citizen-soldiers who saved the Union received far better treatment than their counterparts who labored in frontier garrisons and mounted operations against Native Americans. As late as the 1920s and 1930s, the latter sought equal treatment. In 1927, a report in the House of Representatives recommended raising the upper limit of pensions for Indian war veterans from $20 to $50 per month—and covered anyone “who served 30 days or more in any military organization” from January 1859 through December 1898 “under the authority, or by the approval of the United States or any State or Territory, in any Indian war or campaign.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Citizen-soldiers received far better treatment than their counterparts who labored in frontier garrisons.[/quote]

A hearing in January 1936 revealed that inequities lingered. Congressman John W. McCormack of Massachusetts, who served in World War I and later became speaker of the House of Representatives, complained that Civil War veterans could receive $100 per month while Indian war veterans were limited to half that sum, despite service “rendered in opening up the great frontier.” Another member of Congress remarked that Indian war veterans occupied “a class by themselves in the history of our country” and deserved to be treated better. The cost of fairness would not have been great. At their peak in 1896, Indian war veterans and their widows on the pension rolls numbered 6,955—compared to almost a million Civil War pensioners. By January 1936, just 3,661 men, with an average age of 74, remained on the rolls.

Anyone seeking to characterize the relationship between the Confederate and Indian wars of 1861-65 should take seriously participants’ testimony. Algernon S. Badger will contribute a final word about 19th-century attitudes. A native of Massachusetts who finished the Civil War as lieutenant colonel of the 1st Louisiana Cavalry (Union), Badger speculated in the summer of 1865 that some “cavalry will undoubtedly be sent up on the Indian frontier as the Indians are committing numerous depredations.” Badger had no desire “to chase Indians,” he told his father: “After the work of the past four and half years, it would seem boys play.”

Gary W. Gallagher taught for 30 years at Penn State University and the University of Virginia. The author or editor of more than 40 books, he also has played an active role in battlefield preservation. He is writing a book about how Americans, both in academia and in popular culture, understand the Civil War.