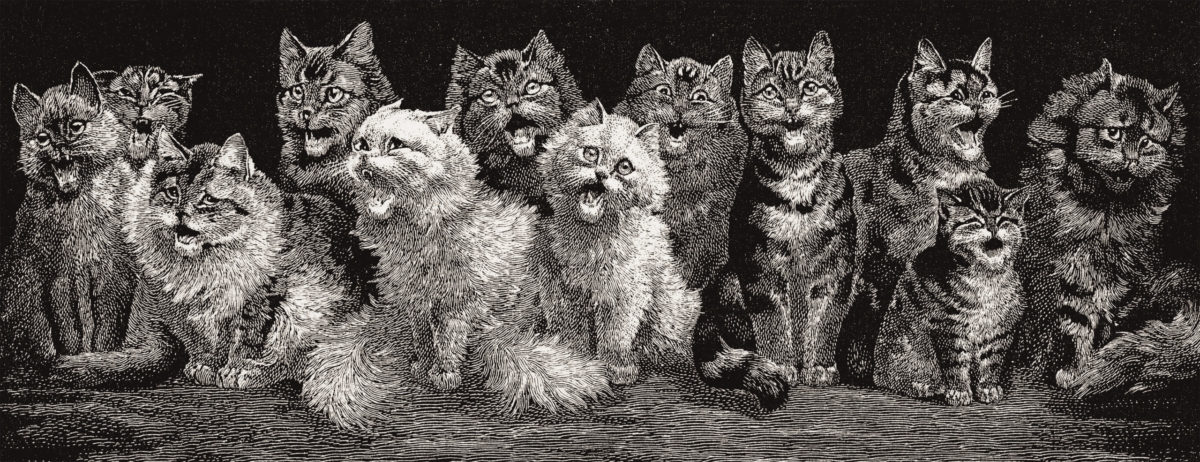

As disturbers of the peace, neither celebrating cowboys nor dueling gunmen could hold a candle to the feral cats that roamed the streets and disrupted the dreams of folks in mining towns, cow towns and other settlements across the Old West. Meowing, trilling, hissing, growling, snarling, grunting, screeching and wailing at all hours of the night, such roving felines were to nighttime tranquility what dynamite was to solid rock. If period accounts are any indication, for all the good cats may have done in reducing rodent populations, the benefit came at a long-term cost to citizens’ slumber.

Editors and readers alike complained in print of the interminable feline fandangos that shattered the after-hours quietude craved by frontier saints and sinners. The caterwauling came from perches as varied as fences, roofs, bushes, wagons, front porches and the neighbor’s yard, invariably when residents were settling in for a long night’s sleep.

“The cats have been troubling us considerably of late,” Nevada journalist and diarist Alfred Doten wrote of a May 1874 evening in Gold Hill, “every night holding caucuses on the back porch and making a hideous noise, so that I had to raid out at them with oyster cans and beer bottles two or three times a night.”

The complaints came in from far and wide. “The cat shooting season will commence shortly in this place if the brutes don’t make less noise of nights,” vowed a sleep-deprived editor in Eureka, Kan., in the summer of 1869. “A fellow isn’t half so much bothered by the dog days as he is by the cat nights,” wrote a wag in Fulton, Mo., in September 1878. “Musical concerts by Thomas cats are becoming common these moonshiny nights,” quipped a Texan in the Brenham Weekly Banner in May 1877. “A cat is not as large as a steam piano,” observed The Kansas City Evening Star in September 1881, “but it can make more noise when fully aroused.” That lesson became all too apparent one star-crossed night in August 1891 when boarders at the Windsor Hotel in Anaconda, Mont., “had their peaceful nocturnal slumbers aroused by the unearthly squalling of a cat.”

Portland’s Morning Oregonian likened the melodies of “a thousand amorous John Thomas cats” to the city’s Chinese theaters, “[making] night hideous with banging of gongs and with songs in a falsetto key.” Addressing the ceaseless urban cacophony in an 1874 editorial, The New North-West of Deer Lodge, Mont., summed up the situation: “The American people are a patient race; but there is a place where they draw a line. It is at abnormally vociferous cats.”

In February 1878 the rare appearance of a two-headed kitten in Guthrie County, Iowa, made the news some 300 miles south in Eureka, Kan., whose Herald observed, “When a man sits down and reflects that the next generation of cats may possess double the facilities for making nocturnal noises that their fathers have, it is enough to destroy all the theological theories of the age.”

The San Francisco Chronicle raised the alarm in the spring of 1889 when an unnamed municipality in Iowa shipped unwanted cats west to the Dakotas. “Three carloads of cats!” the paper mused. “Only imagine the concentration of cussedness which that implies. Fancy the moonlight serenades on the back fences and shed roofs, the number of flying bootjacks and soap dishes, and the amount of Dakotan swear words which are latent in three carloads of cats.”

An 1893 editorial in Kansas’ Coffeyville Weekly Journal feigned sympathy for the plight of the feline. “The cat is a fine musician,” it noted. “As a midnight serenader he attracts more attention than a mandolin club, quartette or string band. He never fails to receive an encore, generally consisting of bootjacks, stove legs, brick bats and anything else that may happen to be handy.” The Emporia Daily News concurred, noting, “George Washington was so fond of cats that he would get up in the middle of the night to throw a bootjack at them.”

While it appears the bootjack (a V-shaped wooden wedge used to remove one’s own boots) was the weapon of choice to hurl at wailing, cantankerous cats, it was far from the only anti-feline missile employed. “Every adult cat has had more costly articles thrown at it than any opera singer that ever lived,” The Arizona Daily Star observed in 1882, “for when a man’s state of mind becomes such that he gets out of bed to serve his country in this cause, the first article he touches is the thing that goes, whether it be a coal scuttle, an ivory-backed hairbrush or a diamond bracelet. Man has the right of this conflict, and he will surely win if he lives long enough.”

Frontier folks threw so many items at cats that clever youngsters learned to profit from it. According to reports from Iowa, one boy who’d learned to imitate a cat’s meow would visit neighbors’ yards at night, start caterwauling and then collect and sell anything worthwhile thrown at him. A boy in Utah tried something similar with promising results—that is, until he got “a load of bird shot from a double-barreled shotgun.”

Such was his desperation for a full night’s sleep that Comstock Lode journalist and satirist Dan De Quille conceived a bootjack packed with dynamite that “explodes as soon as it hits the ground and annihilates the cat.” Never mind that his explosive epiphany came on the heels of a devastating 1875 fire that ravaged Virginia City, destroying 2,000 buildings and mining properties valued at upward of $10 million . Terrible as the fire had been, the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat suggested Comstock denizens had reason enough to be thankful. “There’s a silver lining in the Virginia City cloud in the fact that from 15,000 to 20,000 prowling pussycats are estimated to have gone up in the flames of the recent conflagration.”

While it was the ravages of fire that decimated the cats of Virginia City, elsewhere in the West the nocturnal crooners were more likely to be shot, clubbed, lynched or drowned alive. Like outlaws and coyotes, cats even had bounties placed on their heads. “Speaking of the grand and beneficent results of science,” the Newton Kansan reported in 1888, “the senior pharmacists of the Kansas university are offering 15 cents for cats, dead or alive.”

In 1875 south-central Nebraska’s Red Cloud Chief hailed a resident of Beatrice, four counties to the east, who “shot 118 cats in three minutes by the light of the silver moon.” An 1886 edition of The San Saba News praised the unknown persons who had shot some of that central Texas community’s stray dogs and noted, “If they would kill about a hundred cats, while they had their hands in, they would receive the gratitude of a long-suffering public.” In February 1894 Arizona Territory’s Tombstone Weekly Epitaph reported a step in that direction. “Two shots fired in rapid succession early this morning on Fremont Street,” the paper wrote, “resulted in the ninth death of a big black cat whose melodious voice had kept the neighborhood awake the greater part of the night.”

A May 1877 report out of Lawrence, Kan., told of a “champion cat-destroying angel” that over the past 10 days had “made 38 full-grown cats bite the dust, and that, too, without the aid of shotgun or poison.” The “angel” in question would catch cats by the tail, then cruelly bash them against a tree, a fence or a wall. “With three cheers, a swing and a tiger, pussy is no more,” the Daily Journal bluntly reported. But even sleepless townspeople had humane limits. In March 1894 officials in San Francisco arrested one John “Judy” Johnson, 13, and Arthur “Fishy” Whiting, 15, “whose studies run mostly to dime novels and the soul-harrowing order of drama,” for having lynched a number of cats—though their slaying of a dog was what may have landed them in jail.

Newspapers could be faulted for such slips in civility. The editors of various Kansas newspapers, for instance, put forth equally barbaric solutions to the cat-astrophe. One suggested administering a half pound of shot to “sympathetic cats,” which would “bear fruit in increased hours of slumber.” Another held to the credo, “If your dog goes mad, kill your cat.” Perhaps the most heartless proposed “amputation of the tail just back of the ears.” Others looked to agriculture for a remedy. “Now is a good time to plant cats,” editorialized one paper in the summer of 1872. “The cats should be prepared with a club, revolver or some other farming utensil and then planted under a peach tree. If you have not got a peach tree, plant anywhere. Plant as many as you can, and plant deep. This branch of agriculture is much neglected.” In 1888 the Abilene Daily Reflector proposed planting a cat with every new tree so western Kansas could grow forests. “If the cats hold out, 20 years from now where buffalo grass and prairie dogs exist will be huge forests and logging camps.”

More humane was the enterprising Oklahoma newspaperman who, on learning of a $10 reward for the return of a lost cat in a neighboring city, wrote, “Let us send over a thousand or two—it may be in the lot.”

But such restraint proved the exception rather than the rule. A newspaper in California, for example, offered the story of a man who entered a gun shop and was offered a six-shooter. “Better make it a nine-shooter,” he replied. “I want to kill a cat.”

Animosity toward cats persisted far past the frontier days and nights, mostly because the felines refused to shut up, especially after dark. The universal disgust with their nighttime antics was perhaps best summed up by a young lad who had raised cats for a time before expressing misgivings to his mother. “Mama,” he said, “I hope the next cat I have will be a dog.”

Texas author Preston Lewis, a past president of Western Writers of America, is an award-winning author of more than 40 books. For further reading see his Cat Tales of the Old West: Poems, Puns & Perspectives on Frontier Felines.