FDR got polio, but polio didn’t get him

AS THE 20th CENTURY dawned, American summers stopped being times of fireflies, baseball, and beaches to become seasons of terror. Each year with warm weather came some new proscription for parents: Keep children away from crowds, ice cream parlors, public swimming places. Do not send kids to the movies or let them overexert, or get too hot, or too cold. Keep little ones away from dusty streets, swat their fingers away from their noses. Let no fly remain alive inside any house. Keep windows closed. No one could follow all those rules, but parents had no other way to try to safeguard children from the scourge of poliomyelitis, a viral disease then called infantile paralysis, and now known as polio.

Polio dates to prehistory, but not until 1894 did the disease break out on a large scale in the United States. That summer’s epidemic, in northern New England, sickened 123 children. Outbreaks multiplied and intensified as the three strains—one mild and flu-like, another

characterized by paralysis, and the most acute, bulbar polio, sometimes causing death—mutated. In summer 1916, all three strains converged in New York City, striking 8,900 people and killing 2,400 children, 80 percent age 4 or younger. Panicked city officials barred children from subways and trains, closed summer camps, and mandated screening of doors and windows in residences. Trying to contain the urban outbreak, health inspectors searched the suburbs for fleeing city children, placing polio refugees under house arrest. The virus spread to 26 other states, causing another 27,000 cases and 6,000 more deaths.

Polio hit quickly—youngsters at play one afternoon found themselves the next morning in ambulances. Polio ward staffs isolated suspected carriers from their families, stripped away and incinerated clothes and belongings assumed to be infected, and put terrified youngsters through excruciating spinal taps. Patients with confirmed diagnoses donned hospital-issue pajamas; a large red dot on the back advertised infectious status. In confinement, patients passed through a week or more of high fever, difficulty breathing, nausea, and muscle spasms. Some came away paralyzed. Paralysis could affect the limbs, but also the abdominal muscles, causing them to tighten so much some patients bent permanently at the waist, perhaps forced to walk on hands and knees. Cases could involve two years of rehabilitation—if a “crippled polio,” as patients were called, was lucky.

Bulbar polio struck the muscles employed to swallow and to breathe, killing by respiratory failure. A bout often began with severe headache, sweating, and vomiting. Soon the patient, unable to cough or to swallow, was gasping and turning blue from lack of oxygen. In an infant, the danger sign came when a baby suddenly stopped crying; doctors would rush to intubate the child, an emergency procedure often undertaken too late.

Adulthood conferred no immunity. As early as 1921, medical authorities were downplaying use of the adjective “infantile” because the disease overtook older children and even young adults, though only a few people in their thirties. But more virulent viral mutations broadened the age range. In 1916, 80 percent of New York City polio patients were 4 or younger, but by 1955, 25 percent would be 20 or older.

Adult onset polio was quite rare when, on August 10, 1921, Franklin Delano Roosevelt fell ill. The gregarious, cheerful politician was vacationing with wife Eleanor and their five children on Campobello Island in New Brunswick, Canada, when he experienced chills, a fever, and loss of feeling in his limbs.

At 39, Roosevelt stood just over six feet tall. A vigorous, athletic fellow in the prime of his life, he golfed, played tennis and field hockey, and ran cross-country. He chopped trees, sailed iceboats, and sledded with his young children. A scion of a wealthy old Hudson Valley family, Roosevelt had a law degree but, under the influence of energetic presidential cousin Theodore, he had gravitated to public service. In 1910, the younger man won election to the New York State Senate. During the world war, he served as assistant secretary of the Navy, and in 1920 had been the Democratic candidate for the vice presidency. He was looking forward to a bright future.

However, within 24 hours of taking to his bed at Campobello, Franklin Roosevelt could not even stand. Local doctors attended him. Nine days later, his paralysis had spread. He could feel nothing from the neck down.

On August 25, a physician summoned from Boston diagnosed polio. In time Roosevelt’s arms worked again, but not his legs. Even so, through sheer will he resumed his political career to extraordinary result. Never denying that he had polio—and never identifying as its victim—Roosevelt held himself up as having defeated the disease and its paralysis, and, with the same vigor, worked to help his country defeat polio as well. In the words of biographer Roger Daniels, the story of FDR and infantile paralysis is “not what polio did to Roosevelt, but what Roosevelt did for polio.”

A vacationing Franklin Roosevelt was celebrity enough that bad news involving him intrigued the press. Interest built among local reporters when Roosevelt delayed his departure from Campobello until after Labor Day, ostensibly to avoid traveling in hot weather. Political manager Louis Howe announced that FDR would be leaving his family home by boat and landing on the docks at Eastport, Maine. While newshounds milled around the wrong end of town, Howe was having the stretcher-bound Roosevelt transported by launch to a different dock and delivered to the railway depot, where handlers loaded him onto a baggage cart and trundled him into his private car. By the time reporters found the correct platform and rail car, the object of their attention was seated happily at an open window, smiling and joking. Roosevelt, his doctors, and his family rolled back to Manhattan. Only then did the world learn he had polio.

If his mother had had her way, Roosevelt would have retreated to the family estate at Hyde Park, New York, and lived as an invalid, but FDR responded to his condition with resilience and determination. He needed round-the-clock help—someone to carry him up and down stairs, maneuver him into and out of bed, wash him, help him empty his bowels, lift him into and out of chairs and vehicles. Yet Roosevelt managed his life so successfully that his “disability was of little interest to the voters,” wrote historian David Oshinsky.

“The doctors are most encouraging,” Roosevelt claimed in September 1921, declaring he had “been given every reason to expect” that he would overcome paralysis. In addition to his family’s status and considerable fortune, he had the support of George Draper, his personal physician and a childhood friend.

Draper, who harbored grave doubts about whether his pal would walk again, kept quiet about how he was “much concerned at the very slow recovery” FDR was making. Draper wrote later that he hesitated to quash his friend’s hope of reversing paralysis through hard work “because the psychological factor in his management is paramount.”

Roosevelt’s optimism extended to his political career, which for now had to defer to his recovery. Even so, almost from the moment his employer fell ill, Howe was mounting a cheerfully optimistic—or willfully deceptive—line of reasoning in the press. A day after physicians at Presbyterian Hospital confirmed the polio diagnosis, The New York Times was reporting that Roosevelt was “seriously ill” but “improving.” The article did not mention polio.

“His physician is confident of his ultimate recovery,” the New York World wrote.

Roosevelt “will not be crippled,” Draper had told the Times. “No one need have any fear of permanent injury from this attack.” Newspapers across the United States reproduced the

statement. The Washington Post reported the increasingly famous patient to be “nearing recovery.”

Six weeks into his stay at Presbyterian, Roosevelt still could not stand. But the fact that he could wrestle himself into a wheelchair persuaded doctors to discharge him. He returned to his East 65th Street townhouse, three blocks from Central Park. He and his medical staff developed an exercise regime meant to restore the use of his legs and help him cope. Hoisting himself on straps dangling above his bed, he did sets of pull-ups. To keep his abdominal muscles from shortening and distorting his posture, doctors encased him for weeks in a full body cast—a circumstance Eleanor Roosevelt described as “torture” that her husband bore “without the slightest complaint, just as he bore his illness from the very beginning.” Stamina revived, Roosevelt donned leg braces. These contraptions let him practice standing on his own—until he fell. Someone would pick him up, and he would fall again. He imitated the act of walking by gripping parallel bars and using his increasing upper body strength to drag his inert lower frame forward. He rehearsed rescuing himself in a fire by throwing himself from bed or chair to the floor and with hands and elbows dragging himself to an exit. Seeing her husband demonstrate this hard-learned technique, Eleanor ran from the room crying.

By May 1922, Roosevelt’s condition had improved enough to permit him to travel to Boston. At Massachusetts General Hospital, technicians fitted him with new braces and taught him a new exercise and movement regime. He began using crutches, which sufficed until October. One day that month, as he was traversing a Manhattan building lobby with a chauffeur’s aid, the crutch tips slipped. Roosevelt came to spectacular grief, tumbling to the polished floor—in front of a crowd.

Realizing scenes like that would doom him politically no less than the sight of him in a wheelchair, Roosevelt determined to walk—or at least appear to. Standing arm in arm with someone large and strong enough to ballast him—often adolescent son James—he rehearsed holding a cane and executing a shoulder-powered shuffle that shifted his weight from side to side, moving his useless, braced legs. The process was arduous and Roosevelt struggled to maintain an even emotional keel.

The real test came in June 1924—less than three years after he was stricken—when Roosevelt’s party invited him to address its quadrennial national convention in Manhattan. On the appointed afternoon, the man of the hour summoned his resources and labored to the podium at Madison Square Garden. Beaming at the cheering horde with a wide smile, Roosevelt entered New York Governor Al Smith’s name into contention for the Democratic presidential nod.

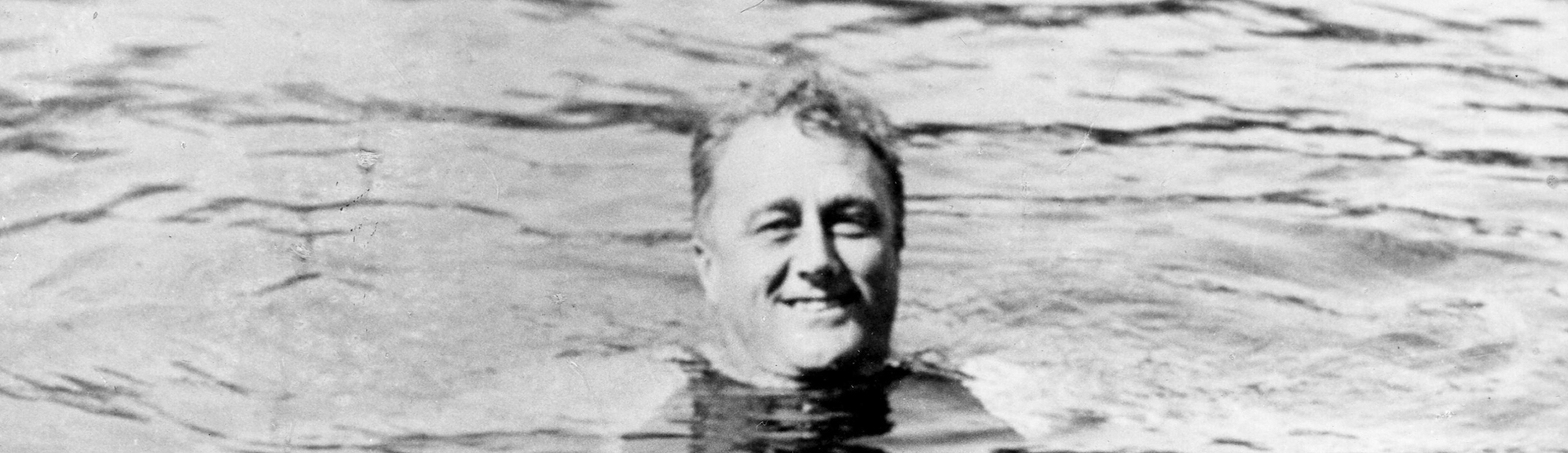

For the next three years, however, Roosevelt retreated from public life. In October 1924, he first visited Warm Springs, Georgia, a resort town south of Atlanta. Word was that upon exercising in the 88o mineral-rich pools there, several crippled polios had found they could walk. Immersed, Roosevelt found he could stand upright unassisted, move his legs, even walk and swim. He happily relayed to Eleanor that “the walking and general exercising in the water is fine and I have worked out some special exercises.” The Atlanta Journal reported on the benefits Roosevelt experienced in the waters at Warm Springs, adding that he planned to build a cottage of his own and “spend a portion of each year there until he is completely cured.” By 1926, Roosevelt so believed in Warm Springs that he stretched his strained personal finances to buy the property. In 1927 he established the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation, a non-profit that could receive tax-free gifts and grants that would allow the facility to help others in his situation.

Accustomed to seeing Roosevelt use only two canes, ambulating with his tortured shuffle, advisors and pundits began to tout him as the Democrats’ man for the presidency in 1928.

Impossible, Roosevelt said; he barely was able to walk with with the assistance of braces, crutches, and canes, and often had to be carried. He continued his rehabilitation—and the publicity campaign positing his inevitable recovery.

To maintain his upper body, Roosevelt doggedly worked out, sometimes spending three hours a day on the parallel bars. By September 1928, in the privacy of his Warm Springs cottage, he had managed several steps without cane or crutch. That autumn, he sought and won New York’s governorship.

“I just figured it was now or never,” he told one of his sons.

Throughout the gubernatorial campaign and Roosevelt’s tenure as governor, Louis Howe continued to ballyhoo his boss’s physical fitness, taking care to douse rumors that Roosevelt’s health problems came from untreated syphilis and that physical disability had sapped his mind.

The highlight of the effort to sell FDR’s strength and vigor was a grandiose declaration that “every rumor of Franklin Roosevelt’s physical incapacity can be unqualifiedly defined as false.” This assertion appeared in the July 25, 1931, edition of Liberty magazine. The popular weekly’s article began with journalist Earle Looker challenging Roosevelt to prove his health and suitability for the nation’s highest office.

The theoretical candidate responded head on, submitting to a thorough examination. Three medical specialists unequivocally declared him “physically fit,” with healthy organs, an aligned spine, and no known disease. Liberty left out the detail that Looker, a Roosevelt family acquaintance, had confected the whole thing. In 1932, Looker published a biography, This Man Roosevelt, a fluffier version of the article.

Better conditioned, more seasoned in his adaptive strategies, and blessed with an opponent, Herbert Hoover, who had the Depression draped across his shoulders, Roosevelt easily won the 1932 election. In his March 4, 1933, inaugural address he reassured a fretful nation that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” Less well known is his next sentence, in which he defined fear as “nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.” That double entendre invited listeners to take heart from FDR’s determination to apply the rigor he had shown in overcoming paralysis and taking the White House to the task of restarting a ravaged economy and uplifting a demoralized populace.

Organizing what disability advocate Hugh Gallagher called a “splendid deception,” FDR mobilized all available resources to maintain the optimism-cum-pretense that had carried him to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW. He ordered leg braces in an unobtrusive black finish. He had his touring car fitted with a bar he could grip while standing to address crowds. He expanded the Secret Service’s role; besides keeping the chief executive safe, agents searched for alternate entrances so the president could get into buildings away from the public eye. Roosevelt’s guardians installed ramps, made bathrooms accessible, and bolted down podiums. When FDR moved on foot in public, he did so at the center of a knot of Secret Service men, some of the men supporting him by the elbows.

The press helped maintain appearances, adhering to FDR’s wish that he not be photographed or filmed in awkward or vulnerable positions, such as exiting a vehicle or struggling from chair to chair. When Roosevelt did submit to photo sessions, he stage-managed them, as often as possible in the form of press conferences he conducted in the Oval Office. Seated at his cluttered desk with an air of informal industry, he—and his interlocutors—all could overlook his paralysis.

Polio remains incurable, but in 1930, Philip Drinker and Louis Agassiz Shaw of Harvard University invented the iron lung. These ponderous metal cylinders, big enough to hold a person, forced air in and out of the lungs of patients lying within, keeping some alive—but also immobilizing them, separating them from human touch, and reducing their field of vision to what they were able to see reflected in a mirror.

And those were the fortunate few. In 1939, a year of hospitalization for polio cost around $900, a tad more than the average American’s annual income. No federal agency funded treatment or rehabilitation, and less than 10 percent of American families had health insurance.

Against the backdrop of polio’s seasonal terror and the specter of lives spent in iron lungs, President Roosevelt threw his clout into fundraising and research. In 1934, he hosted a “Birthday Ball” to benefit the Warm Springs Foundation. That first January 29, more than 6,000 parties took place nationwide, with the premier event, at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel, featuring a 28-foot-wide cake that fed 5,000 guests. That year’s balls raised more than $1 million, and became an institution. In 1938, Roosevelt founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, focused on finding a cure for polio and assisting patients. The foundation’s efforts kicked off with the March of Dimes—entertainer Eddie Cantor’s pun on the popular “March of Time” newsreels—as mothers went house to house around the country asking neighbors to contribute ten cents to help advance polio research. That first campaign raised $2,680,000.

Reelected three times, beloved by millions—and pilloried by other millions—overseer of the economy’s recovery, pillar of the war against the Axis, Franklin Roosevelt in the execution of his duties as wartime commander-in-chief was “a marvel,” Winston Churchill commented. Even Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin was observed to respond to FDR’s fortitude, affectionately patting his ally’s shoulder during meetings. Gas mask draped on his wheelchair, Roosevelt in wartime left Washington more than he ever had. On some visits with wounded troops, he allowed GIs to see him in his wheelchair. However, his schedule forced him to give up his exercise routine, and in early 1944 his health entered into rapid decline.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt died in his cottage at Warm Springs on April 12, 1945, probably of a cerebral hemorrhage. The following year, the U.S. Treasury Department fittingly memorialized his support for polio research by putting his face on the ten-cent piece.

By the 1950s, thanks to the March of Dimes, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, and heightened public support, more than 80 percent of American polio patients were receiving significant financial and medical aid.

Donations to these entities helped fund Dr. Jonas Salk’s research into the vaccine named for him. First made available in 1955, the Salk vaccine was outstandingly effective: in the early 1950s, the U.S. averaged over 45,000 polio cases per year. By 1962, fewer than 1,000 cases were presenting annually.

As generations unfamiliar with polio or President Roosevelt have come of age, an impression has arisen that FDR was “hiding” what polio had done to his body. This is not true. Americans may not have always recognized or remembered that their president was a paraplegic, but Roosevelt’s limitations were popular knowledge, as was his dedication to polio research and treatment. FDR’s legacy is not that he conned fellow Americans, but that he overcame polio’s limitations to become one of the greatest advocates on behalf of fellow patients. In her autobiography, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote that for her husband polio was “a blessing in disguise, for it gave him strength and courage he had not had before. He had to think out the fundamentals of living and learn the greatest of all lessons—infinite patience and never-ending persistence.”