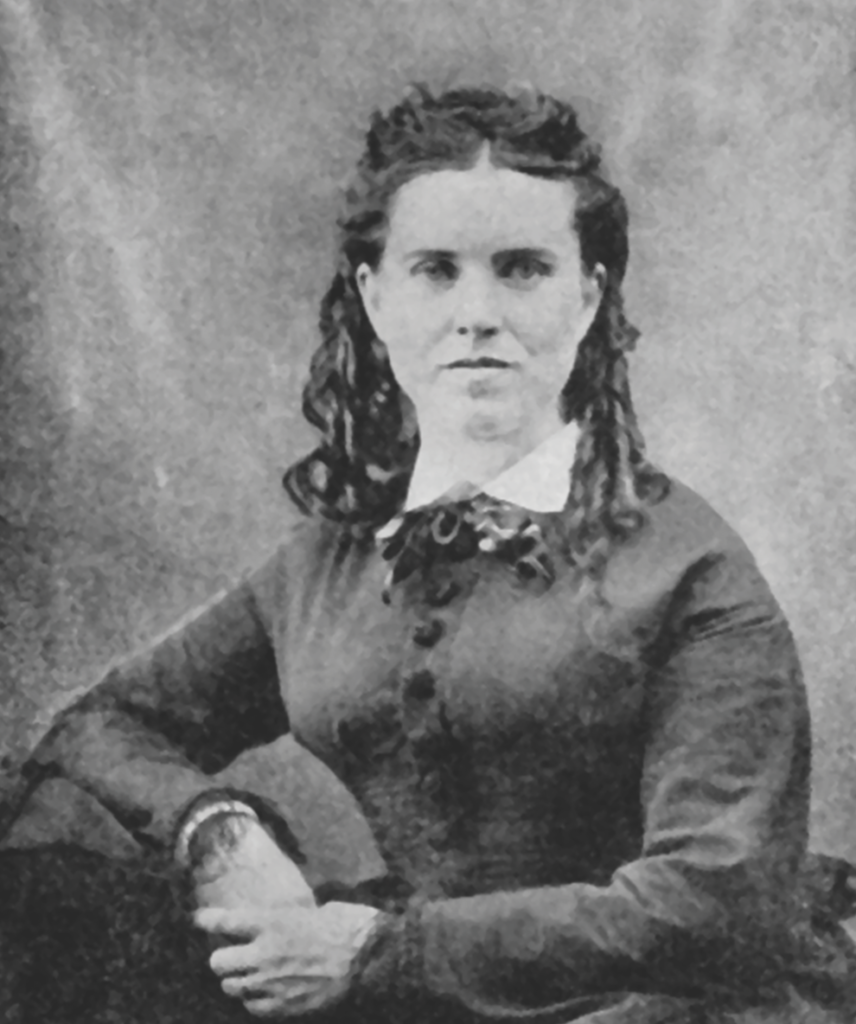

Fanny Kelly was desperate. Captured by a Lakota war party on July 12, 1864, in Dakota Territory (present-day central Wyoming), she became the trophy bride of their septuagenarian chief.

A week after Fanny’s capture the elderly chief’s brother-in-law gave her a pair of stockings, a gesture that provoked dire consequences. Flying into a jealous rage, the chief abruptly shot one of the brother-in-law’s horses. Fanny described what happened next in her 1871 bestseller “Narrative of My Captivity Among the Sioux Indians:”

“His brother-in-law, enraged at his arrogance, drew his bow and aimed his arrow at my heart, determined to have satisfaction for the loss of his horse…when a young Blackfoot [Sihasapa Lakota], whose name was Jumping Bear, saved me from the approaching doom by adroitly snatching the bow from the savage and hurling it to the earth.”

BORN IN CANADA

Born in Ontario, Canada, in 1845, Francis “Fanny” Wiggins had immigrated to Kansas when she was 11. In 1864 Fanny, husband Josiah Kelly and their adopted daughter Mary had joined a small party of emigrants bound for Oregon. They had just crossed Little Box Elder Creek (east of present-day Casper) that July 12 when attacked by the Lakotas, who killed three men, wounded another and captured Fanny and Mary, as well as Sarah Larimer and son Frank.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Fanny’s husband and two others had eluded the war party, and Sarah and Frank Larimer soon escaped. Fanny dropped Mary along the trail and told her to backtrack, hoping her daughter would manage to elude captors. But she later saw her daughter’s shawl and scalp dangling from a Lakota’s saddle.

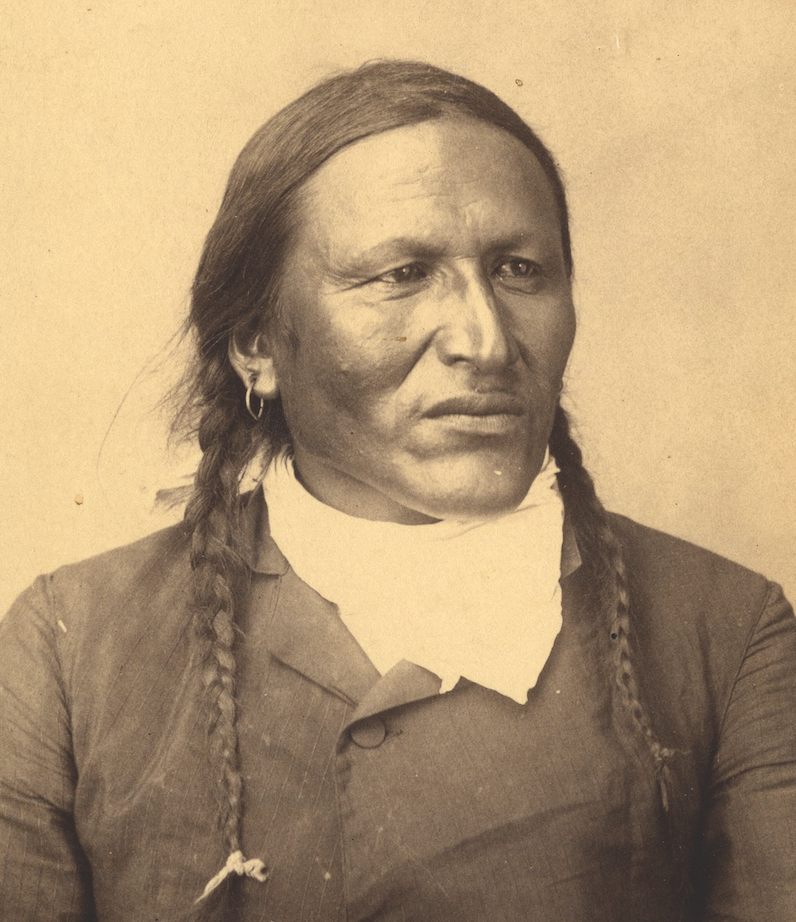

Jumping Bear (aka Charging Bear) was born circa 1836 and baptized at age 3 as John Grass by Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, a Belgian-born Jesuit noted for his missionary outreach to American Indians. By 1872 Grass would be an important chief. As Fanny tells it, in the weeks after he saved her life, her rescuer made romantic advances to her.

“I replied that I did not fear him,” she wrote, “that I felt grateful for his kindness and protection, but that unless he proved his friendship for me, no persuasion could induce me to listen.”

Promising he would be rewarded, Fanny ultimately persuaded Grass to carry a letter to nearby Fort Sully. “The contents of the letter,” she recalled, “were a warning to the ‘Big Chief’ and the soldiers of an intended attack on the fort and the massacre of the garrison, using me as a ruse to enable them [the Lakotas] to get inside the fort.” She included a testimonial for Grass and beseeched the soldiers to rescue her.

According to Fanny’s account, when the advance party of eight chiefs rode into the fort with their captive, the soldiers yanked Fanny aside and slammed the door in the faces of the would-be war party. Finally free after five months in captivity, Fanny later received $5,000 from Congress for saving the fort.

GRASS’S ACCOUNT

In 1915 an elderly Grass told his adopted son, North Dakota National Guard Captain Alfred Burton Welch, his version of events. Grass claimed Fanny was initially the captive of a larger band of Hunkpapas affiliated with his own Sihasapas.

“We wanted that white woman, but we did not want to fight for her if we could help it, for there were more Hunkpapa men,” he recalled. “We sent for eight of the best warriors of the Hunkpapa…gave them much to eat and some fine clothes and some feathers.…Then they made this plan: We would give each of these brave eight men a horse. They were to help get her for us. So they said, ‘Yes,’ and went away.”

The eight warriors told Fanny’s owner they would trade him horses for the woman, but if he refused, they would bury him. Not wanting to die that day, the man agreed to negotiate. “So,” Grass continued, “we got the white woman for 16 horses…all my own horses, and they were good ones, too.…After a long time we took the white woman to Fort Sully and gave her to the white people there. She was glad to be with white people again.”

By all accounts Grass was both an adept warrior and diplomat. Through the 1850s and ’60s he fought against rival tribes, but he realized the whites were too numerous and well equipped to be driven away. Family lore has it Grass was in Sitting Bull’s camp at the Little Bighorn in June 1876 and had joined the Hunkpapa and Oglala warriors in battle to stave off a slaughter of Indian women and children.

In August he was back at the Standing Rock Agency, telling post commander Lt. Col. William P. Carlin—who considered the Lakota “treacherous”—that George Custer had brought the whole thing on himself. Grass, whose absence from the agency during the battle had not been noticed, also reportedly urged any willing Indians at Standing Rock to take up arms and join Sitting Bull’s people. There were few takers. Soon running short of food, those who did not join Sitting Bull in Canada returned to their agencies. In 1881 Sitting Bull himself returned.

That presented Grass with a new diplomatic challenge: to save as much American Indian land as possible without touching off further bloodshed. He worked with Gall, the Hunkpapa war chief at the Little Bighorn, who had also come to realize armed resistance was futile. To Sitting Bull’s irritation, Grass stepped forward as spokesman for the American Indians at Standing Rock.

PROUD GRANDFATHER

He led opposition to a proposed 1882 land cession and efforts by the 1888 Pratt Commission to break up the Great Sioux Reservation and sell the surplus land to white settlers. But in 1889, as the Crook Commission met at Standing Rock, Agent James McLaughlin convinced the Sioux the government would simply seize the land if they didn’t sell. Grass and most of the other leaders buckled.

The Lakotas got approximately their present-day reservations in South Dakota and North Dakota and $1.25 an acre for the “surplus” land. A year later American Indian police at Standing Rock killed Sitting Bull, the last opposition leader, supposedly while resisting arrest. Two weeks later the Sioux wars ended in bloodshed at Wounded Knee.

Though disheartened by perfidy, Grass was proud when grandson Albert shipped off to fight for the United States in World War I. John Grass died on May 10, 1918. Albert died two months later in Soissons, France.

In 1921 John Grass’ widow told adopted son Welch of her late husband’s last encounter with Fanny Kelly, in the nation’s capital. “At Washington once,” she recalled, “this woman came and shook hands with him and called him kola mitawa (“my friend”) and was glad to see him.”

By the time of that recollection, Fanny Wiggins Kelly Gordon had died wealthy—and a friend of the Indians, especially Jumping Bear—in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 15, 1904.

This story originally appeared in the April 2017 print edition of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.