THINGS WERE spiraling out of control for John Brown. From less than 100 yards away, Osborne Anderson could see that the radical abolitionist had barricaded himself in the tiny fire engine house. The little brick building, at the federal armory and arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, was crowded with Brown’s followers, their hostages, and slaves the raiders had come to free. Outside, a mob of citizens and militiamen was shouting for blood. It was Monday, October 17, 1859. Anderson was watching the chaos from another arsenal building. Clearly, Brown’s scheme to spark a slave uprising that he hoped would rage throughout the South had failed.

With Anderson was Albert Hazlett, 22. Raw-boned and muscular, the Pennsylvanian had signed up with Brown to fight slavery in Kansas. At one point Shields Green joined the two. Green, an escaped slave, had met Brown through Frederick Douglass when Brown tried in vain to persuade the freedman abolitionist to join the raid. Green was “the most inexorable of our party, a very Turco in his hatred against the stealers of men,” Anderson wrote later. Green also saw that Brown had no chance, but nonetheless returned to the engine house to share his leader’s fate. Anderson, 29, had joined Brown’s improvised war on the peculiar institution with enthusiasm. Now he knew Brown was doomed.

His own chances, Anderson believed, were a bit better.

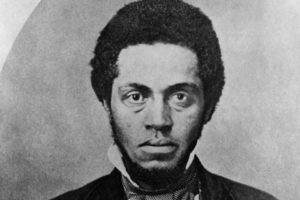

Osborne Perry Anderson was a “tall, handsome mulatto, with a thoughtful face, sadly earnest eyes, and an expression of intellectual power that impressed toe observer strongly,” wrote a contemporary. He was born in West Fallowfield, in Pennsylvania’s Chester County, in July 1830, to parents who were free blacks; his slaveholding grandfather was white. Anderson lived with his father until age 19 or 20, receiving a common school education. He loved to read. Growing up in a state rife with abolitionist sentiment, he hated human bondage. Pennsylvania was home to anti-slavery activists like William Goodridge. Born a slave in Baltimore in 1805, Goodridge became free at 16, moved north, and opened a barbershop in York. Business-minded, he acquired a dozen properties and ran a railroad, the Reliance Line. Besides hauling freight, Goodridge used his 13 railcars to smuggle escaped slaves to Philadelphia and points north—an Underground Railroad conductor worthy of the title. Another abolitionist figure in Pennsylvania was Philadelphian William Still. Born free in New Jersey in 1821, Still started working for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in 1844 and later chaired the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, which aided fugitive slaves. According to one count, Still helped 649 slaves reach freedom.

Anderson developed into a passionate abolitionist. As a biographical note in his 1861 memoir put it, “He often expressed to his father great regret at his inability to assist the oppressed and wronged of his race who were then in bondage in the South, stating that he was satisfied that God who created us all free and equal never intended his people to be held this way in slavery.”

As a youth, Anderson met Mary Ann Shadd, and her parents, free black abolitionists. Shadd became a teacher in New York City. In 1851, she moved to Canada, a magnet for African-Americans seeking to avoid slavery’s reach, especially after passage in 1850 of the Fugitive Slave Law. In Chatham, Ontario, 50 miles west of Detroit, Michigan, Shadd—North America’s first black female newspaper publisher—oversaw the Provincial Freeman. When Shadd’s father and uncle gravitated to Chatham, Anderson, now a young man, came along. Shadd hired him as a subscription agent and printer.

In April 1858, Anderson met John Brown. The abolitionist had become a legend among foes and friends of slavery for his willingness to take up the gun and the sword. Sporting a white beard that bespoke his Calvinistic intensity, Brown had come to Chatham to convene like minds; his zeal impressed the young printer. “He realized and enforced the doctrine of destroying the tree that bringeth forth corrupt fruit,” Anderson wrote. “Slavery was to him the corrupt tree, and the duty of every Christian man was to strike down slavery, and to commit its fragments to the flames.”

To his 46 delegates, Brown, who had been fighting slavery in Kansas, revealed a new strategy—he would spark a slave insurrection across the South. He would establish fortified sanctuaries in the Appalachian Mountains for escaped slaves to use as bases in making war on their former oppressors.

As evidence of his seriousness, Brown presented to the delegates for ratification a “Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States”—a preamble enumerating slavery’s evils and 48 ordinances outlining a reformed, anti-slavery U.S. government. The document included oddities; Article XXXV bore the title “No Needless Waste.” The delegates elected Brown their commander-in-chief. For their “secretary of war,” they selected John Kagi, formerly a lawyer, teacher, and journalist and now unofficial second-in-command to Brown. The convention also selected Osborne P. Anderson, the quiet, reserved printer, as a member of its congress.

Brown spent almost a year staging his insurrection. As “Isaac Smith,” he established himself in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where he stockpiled supplies and weapons. From a Connecticut blacksmith Brown ordered nearly 1,000 pikes with which to arm the slaves he expected to join his rebellion.

The first target, Harpers Ferry, Virginia, lay 50 miles south on a tongue of land at the confluence of the Potomac and the Shenandoah rivers—a place of singular beauty set off by cliffs rising precipitously above wide waters. Besides the rivers, the town had rail lines and the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal—and a federal armory, arsenal, and rifle factory, whose inventory would further arm the uprising. From a widow named Kennedy, “Smith” rented a hillside farm in Maryland, five miles outside Harpers Ferry. From there, in October 1859, Brown planned to ignite what he expected to be a conflagration purging America of its original sin.

Brown recruited Anderson and 20 others, including Brown’s sons Owen, Oliver, and Watson, and two of his son-in-law’s brothers, Dauphin and William Thompson. Among the insurrectionists was the hot-tempered Aaron D. Stevens, a Mexican War veteran court-martialed for attacking a U.S. Army officer. Escaping from Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, Stevens joined an anti-slavery militia, leading him into Brown’s circle. Anderson was one of the party’s five black insurrectionists, along with Shields Green; Dangerfield Newby, a former slave intent on buying his wife and children out of bondage; Lewis Leary, who had left his wife in Oberlin, Ohio, to join Brown; and Leary’s nephew, John Copeland. Other raiders included Albert Hazlett; John E. Cook, a ladies’ man who while scouting Harpers Ferry for Brown had married a young townswoman; Charles P. Tidd, a Maine native “fond of practical jokes and sharp teasing”; William Leeman, 20, another Mainer and the youngest raider; and Francis Meriam, the last of Brown’s followers to reach the Kennedy farm. Annie Brown, the leader’s daughter, and Martha Brown, his daughter-in-law, tended house for the raiders until the end of September, when Brown sent the women away.

On September 13, a Tuesday, Anderson left Chatham to join Brown. Anderson traveled to Philadelphia, where he boarded a train for Chambersburg, departing there afoot on September 24. By dark Anderson had walked 16 miles to the Maryland border, where Brown was waiting with a wagon. The men drove overnight to the rented farm, purposefully arriving before daybreak; in Maryland, a slave state, the sight of white and black traveling together could raise suspicion.

Brown’s headquarters for toppling the slave empire was not much to see—“[r]ough, unsightly, and aged,” in Anderson’s eyes. The first floor had a kitchen, dining room, and bedroom; upstairs was a loft where the raiders hid during the day. Anderson compared life there to prison.

When Brown was present, days began with a Bible reading, after which his troops crammed themselves into the loft. If strangers appeared, the men upstairs froze. At night they could step outside “to breathe the fresh air and enjoy the beautiful solitude of the mountain scenery around, by moonlight.”

The morning of Sunday, October 16, Brown read a Bible passage “applicable to the condition of the slaves, and our duty as their brethren,” remembered Anderson, and prayed for divine help in liberating “the bondmen in that slaveholding land.” That afternoon the old man, as Brown was called, issued orders for the coming day’s action. Some men would remain at headquarters, assigned to transfer weapons and supplies to a schoolhouse nearer town that they intended to seize. Others were to secure bridges over the Potomac and the Shenandoah. A third group had orders to seize buildings at the armory and prepare to hold prisoners.

Brown had a list of prospective hostages. He assigned Anderson and others to grab Lewis Washington, a great-grandnephew of George Washington. A wealthy slave owner who lived outside Harpers Ferry, Lewis Washington had inherited items of symbolic importance—a sword Frederick the Great supposedly had given the first president and pistols the Marquis de Lafayette once owned. Brown directed that Anderson personally relieve Washington of the sword. “Anderson being a colored man, and colored men being only things in the South, it is proper that the South be taught a lesson upon this point,” Brown said. Under Stevens’s command, Tidd, Green, Cook, and Leary would back Anderson on this mission, which also included grabbing a slave owner named John Allstadt.

At 8 p.m., Brown departed for Harpers Ferry driving a wagonload of weapons; Anderson and the others walked, “as solemnly as a funeral procession,” to the Maryland terminus of the Potomac bridge. Raiders captured the watchman, secured the span, and crossed on the rails to seize the lightly defended armory and rifle works. They stowed prisoners in the armory’s engine house and sent two men to take the Shenandoah bridge. “These places were all taken, and the prisoners secured, without the snap of a gun, or any violence whatever,” Anderson noted.

Anderson’s squad set out for Lewis Washington’s home. When they confronted the slaveholder, he volunteered to free his Negroes and, “blubbering like a great calf,” begged for his life. Washington appeared startled when Anderson stepped forward to take the sword. Next, the raiders bundled Allstadt, his son, and his slaves into a wagon for the ride to Harpers Ferry. After returning with the hostages, Anderson handed the ceremonial Washington sword to Brown, who buckled on the weapon and asked Anderson to distribute pikes from the wagon to the few slaves present.

By this time the raid had begun shedding blood.

At the rail station, raiders had stopped a Baltimore-bound train. Told to halt, baggage handler Hayward Shepherd kept moving. A raider shot him. The first fatality in Brown’s war on slavery was a free black man.

The first raider to fall was Dangerfield Newby. Harpers Ferry residents and militiamen from the countryside were pouring into town, and on Shenandoah Street one of their bullets felled Newby, a letter from his enslaved wife in his pocket. Souvenir hunters cut off pieces of the dead man’s ears.

The situation deteriorated, and with it Brown’s resolve. “Capt. Brown was all activity, though I could not help thinking that at times he appeared somewhat puzzled,” Anderson wrote. The old man sent Tidd, Leeman, and Cook back to the Kennedy farm with several freed slaves. He posted Leary, Kagi, and Copeland at the rifle factory. Brown told Anderson and Hazlett to hold the arsenal building. Beyond these steps, the raid’s leader seemed to have no plan, and his retreat into the engine house trapped him. Brown sent William Thompson out under a flag of truce; foes grabbed and killed him. Gunmen shot Stevens and Oliver Brown. A bullet claimed Leeman as he tried to escape across the Potomac. Townsmen and militiamen chased Kagi, Leary, and Copeland from the rifle works and into the Shenandoah, where they shot Kagi dead, mortally wounded Leary, and captured Copeland.

Anderson began gauging his chances. From this point his 1861 memoir, A Voice From Harpers Ferry, doesn’t add up, perhaps because, writing as a fugitive, he hesitated to give information useful to prosecutors; he also may have been responding to latter-day accusations that he abandoned Brown. By his own account, Anderson hid with Hazlett in the armory until Tuesday, when U.S. Marines from Washington DC, led by U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee, stormed the engine house. More likely, Anderson slipped away Monday night, before Lee and the Marine contingent had arrived at Harpers Ferry.

Anderson and Hazlett decided “it was better to retreat while it was possible…than to recklessly invite capture and brutality at the hands of our enemies,” Anderson wrote years later in his memoir. “We could not aid Captain Brown by remaining. We might, by joining the men at the Farm, devise plans for his succor; or our experience might become available on some future occasion.”

Anderson and Hazlett climbed out a window and headed to the banks of the Shenandoah. In his memoir, which tests reader credulity, Anderson says he and his companion captured and released a townsman before hiding downstream and trading shots with locals. In this passage he claims to have seen attackers “bite the dust” before their companions withdrew. In any event, the fugitives found a boat and crossed the Potomac to Maryland. They followed the C&O Canal towpath north toward the farm—finding it deserted, as had been the schoolhouse where the raiders had stashed arms.

The path to safety went through Chambersburg, 50 miles away. With that city still distant, Hazlett—exhausted, hungry, his feet blistered—gave up.

“He declared it was impossible for him to go further, and begged me to go on, as we should be more in danger if seen together in the vicinity of the towns,” Anderson wrote later.

Reaching Chambersburg in the middle of the night, Anderson hid his rifle and found the home of an unnamed acquaintance—perhaps Henry Watson, a barber who had guided Frederick Douglass to his August meeting with Brown. “Greatly agitated” to find Anderson at his door, this party nonetheless took in and fed the fugitive. Anderson had just eaten when a federal marshal knocked. As the marshal entered the front door, Anderson slipped out the back. He retrieved his weapon and made for York, another 70 miles east. He hoped to find William Goodridge, the entrepreneurial freedman and Underground Railroad conductor.

Like Anderson’s nameless savior in Chambersburg, Goodridge was discomfited to see the fugitive. Goodridge spirited Anderson from his Philadelphia Street home to another of his holdings, where Anderson hid for weeks in a closet. Once the hue and cry about Harpers Ferry subsided, Goodridge probably ran Anderson by rail across the Susquehanna River to Columbia, an Underground Railroad hub 15 miles east of York.

From Columbia, Anderson traveled to Chester County to find his parents, only to have his father rebuff him, as he later told Brown’s daughter, Annie.

Anderson “told me with tears in his eyes and voice that, while escaping through Pennsylvania, his own father turned him from the door, threatening to have him arrested if he ever came again; and that most of the colored people he met turned the cold shoulder to him as if he was an outcast,” Annie Brown recalled.

Anderson’s next stop would have been Philadelphia, home of one man he knew would not reject him. William Still makes no mention of Anderson in a memoir he published after the Civil War, but the two had met in March 1858, and a month before the raid Brown had been to Philadelphia to meet with Still and other black leaders.

With or without assistance from Still, Anderson departed Pennsylvania for Ohio. In December 1859, Charles Tidd, the raider John Brown ordered to go to the farm from the armory before everything fell apart, said he encountered “Chatham” Anderson in Cleveland.

“He escaped from below with Hazlett but before they got to Chambersburg, ‘Al’ gave out, and so Anderson had to leave him,” Tidd wrote to Owen Brown, who had also escaped to Ohio. Tidd said he and Anderson traveled together to Chatham, where they ran into Francis J. Meriam, another former raider, “so there were three of the originals together.”

Other raiders had made their way from Harpers Ferry, but the ranks of the fallen were growing. Hazlett, captured in Pennsylvania, was tried, convicted, and executed. John Cook was arrested in Pennsylvania; authorities hanged him in Charles Town, Virginia, in December 1859—the same month John Brown, captured by Lee and his Marines, was hanged.

The family took their patriarch’s body to the Brown homestead in North Elba, New York, for interment. One day at North Elba the following July, Annie Brown noticed a figure kneeling at her father’s grave—a black man who appeared to be weeping and praying. Going to the burial site, Annie Brown recognized Anderson. She invited him in; he declined.

“I might not be welcome,” Anderson told his former commander’s daughter. “I have seen you and the Captain’s grave, and now I’ll go.”

But Annie Brown insisted, and Anderson remained at the Brown homestead long enough to be present at an Independence Day ceremony honoring the old man at graveside.

“The harsh manner in which, among others, some of his own relatives had received him, threatening even his arrest in their selfish and cowardly alarm, had made the refined and sensitive man timid even of this hospitality,” Annie told one of her father’s biographers.

As Anderson was leaving the Brown place, he apologized for staying so long “and said he dreaded to go back and into the world where he would be so friendless and alone,” Annie Brown recalled later.

Although a wanted man, Anderson periodically left the safety of Canada for the United States to give speeches and raise money. In January 1861, aided by Mary Ann Shadd Cary—she had married in 1857—Anderson published A Voice from Harpers Ferry, a pamphlet in which he described Brown’s raid and his own escape, contesting claims that local slaves had spurned Brown.

As Shadd Cary and others did, Anderson may have helped recruit African-Americans to fight for the Union during the Civil War. Some accounts have him enlisting, but his name appears on no muster rolls. After the war he moved to Washington, DC. He is said to have visited Harpers Ferry with friends to show where he had fought. Anderson died at 42 of tuberculosis in the capital on December 10, 1872. “Osborne P. Anderson was truly a noble and devoted lover of freedom for all mankind and proved his devotion in a way that many other decided and earnest friends of freedom really had not the courage to pursue, or of which they failed to see the utility,” wrote editors with the New National Era in an obituary in which they observed that attendance at Anderson’s funeral “was not as large as the occasion merited.”

No one knows where Osborne Anderson is buried.