I received some good discussion on my last post. Some took me to task, others were supportive, and still others were non-committal. At issue was the notion of how much of history is an eye-of-the-beholder narrative and how much is—to use a term that seems to have fallen out of favor today—objective truth. I was having some fun last time out with my post-modernist friends in the historical profession who very much subscribe to the first point of view.

Look, I am the last person to argue against the inclusion of new, previously unheard voices. That’s been going on in academic history since at least the 1960s. Women, racial and ethnic minorities, the working classes: folks who previously had been missing in action from the histories finally began to receive the attention that was due to them. Back then, we called it “social history”—a more inclusive kind of history that sought a perspective from the bottom up rather than from the top down. Military historians took to it in a big way, so much so that it became common to speak of a “new military history.” Sure, it’s great to know what FDR or Ike or Bradley or Norm Cota were thinking and doing on D-Day, the traditional commanders-only approach to military history. But I hope we can all agree that it’s just as important to know what PFC John Smith was thinking and doing, not to mention John’s wife, family, and friends back on the home front in Cleveland, Ohio.

Post-modernism is a very different animal. It’s not really interested in giving everyone a say. Rather, it claims that–since we all use language in unique and mutually unintelligible ways—there can never be a true reconstruction of any historical event. We will never really know what happened at Pearl Harbor, post-modernist historians believe, so trying to do so is a waste of time. One way they try to get around this conundrum is to focus on the “history of memory”—to study how Pearl Harbor has been memorialized and how the way we remember it has changed over time. It is not about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor at all, but more about how the government and other “memory elites” have succeeded in forcing their views on the rest of society over time, how they have “constructed a cultural icon” of Pearl Harbor that serves their interests. I love different historical approaches, and history of memory can be fascinating stuff to read, but in the end, I’m like most military historians, I suspect. I’m more interested in the event itself, and I guess I’m never going to be completely comfortable with any discussion that down-plays what actually happened.

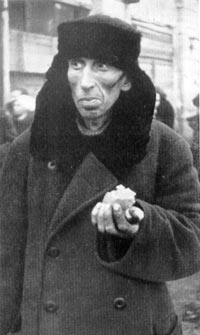

With that in mind, I recently read a very good book by Anna Reid on the siege of Leningrad in World War II. Frankly, it turned my stomach, but not because it is a bad book. Far from it—it’s a fantastic book, and I learned a lot. Reid is a skilled writer, and she does her share of assigning blame and parsing how the post-1945 Soviet government tried to exploit the memory of what happened. To be frank, however, I just can’t get as interested in those angles as I should.

And the reason is this: I can’t get past the simple fact of what happened in Leningrad. Reid’s book is a page turner, and each page is more terrible than the one before. Consider this scenario: What if you lived in New York during some future war and some enemy force cut off Manhattan from contact with the outside world—closed the bridges, blocked the seaward approaches and rivers, shut down the Metro North Line. How soon would the food on that densely populated island last? How about the clean water? Medicine and other essential supplies? Let’s say that the noose is drawn tight in September. What do you think that following winter would be like? How soon would people begin to starve to death? Freeze to death? What would the final death toll be? During a few short months back in 1941, Leningraders learned the awful answer to all of these questions.

And the reason is this: I can’t get past the simple fact of what happened in Leningrad. Reid’s book is a page turner, and each page is more terrible than the one before. Consider this scenario: What if you lived in New York during some future war and some enemy force cut off Manhattan from contact with the outside world—closed the bridges, blocked the seaward approaches and rivers, shut down the Metro North Line. How soon would the food on that densely populated island last? How about the clean water? Medicine and other essential supplies? Let’s say that the noose is drawn tight in September. What do you think that following winter would be like? How soon would people begin to starve to death? Freeze to death? What would the final death toll be? During a few short months back in 1941, Leningraders learned the awful answer to all of these questions.

More of this next week. But I have to warn you: it won’t be pretty.

For the latest in military history from World War II‘s sister publications visit HistoryNet.com.