Joseph McCarthy vaulted to fame as a fearmongering senator. But the war record that got him elected was more fiction than fact.

Joe McCarthy didn’t have to go to war. His job as an elected circuit judge in Appleton, Wisconsin, was important enough to exempt him from military service. It would be nice to say that he volunteered for the best of reasons: a strong sense of duty, a hatred of fascism. It would also be untrue. To his thinking, frontline action was an essential requirement for young politicians. There was but one rule to remember: One had to survive in order to exploit it.

The judgeship bored McCarthy. He viewed himself as a politician, and he had told everyone within earshot of his desire to seek “real” political office. Then the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Like many office seekers, McCarthy knew the value of a war record, and he told a fellow judge, Urban Van Susteren, that he must enlist at once. Van Susteren remembered advising him: “Look, if you’ve got to be a hero to be a politician, join the marines.” McCarthy agreed. Early in 1942 he entered a leatherneck recruit- ing office in Milwaukee and signed on the dotted line.

The news that a circuit judge had traded in his robes for a helmet and rifle traveled quickly through Wisconsin. And McCarthy helped the story along by implying that he wanted no special favors. He said he would serve “as a private, an officer, or anything else.” In fact, McCarthy had already written a letter on court stationery requesting an officer’s rank. He was sworn in as a first lieutenant.

On August 4, 1942, McCarthy began his tour of duty in the Pacific. For almost three years he served as an intelligence officer at Bougainville, in Papua New Guinea, debriefing combat pilots who returned from bombing runs over Japanese–held islands. By all accounts, he did a creditable job; his assignment, while hardly dangerous, was vital to the fliers who took the risks and got most of the glory. In his spare time, McCarthy played poker and acted as the island’s “procurer”—not of women, but of such things as liquor and exotic food. One Christmas he rounded up a few pilots and flew to Guadalcanal, where the men bartered for medicinal brandy, canned turkeys, pineapple juice, and other luxuries. On returning, he held an open house, passing out free food and drink to those who happened by.

But McCarthy was not about to be viewed as a small cog in a big machine. Not when his political instincts told him that those who came home with military honors would be rewarded at the ballot box. Before long, stories about his military exploits began filtering back to Wisconsin. In 1943 the Post-Crescent printed the following dispatch:

Guadalcanal—Every evening the “judge” holds court in a dilapidated shack just off a jungle air strip deep in the South Pacific combat zone. The folks in Wisconsin might be a trifle shocked at his lack of dignity now. He stands bare-chested before his bench, an ancient table reeling on its last legs, and opens court with: “All right, what kind of hell did you give the Japs today?”

That was only the beginning. News reached Wisconsin that McCarthy had become a tail gunner with Scout Bomber Squadron VMSB-235, flying dangerous missions and spraying more bullets (4,700 in one sortie) than any marine in history. As McCarthy carefully molded his image for the folks back home, he told of ever more impressive exploits. In 1944 he spoke of 14 bombing missions; in 1947 the figure rose to 17; in 1951 it peaked at 32. He requested—and received—an Air Medal with four stars and the Distinguished Flying Cross, awarded for 25 missions in combat. Honors poured in from the American Legion, the Gold Star Mothers, and the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

In 1949 the Madison Capital-Times received a letter from Marine Captain Jack Canaan, a flyer who was stationed with McCarthy at Bougainville. It claimed that McCarthy’s only combat experience had been two missions in one day. “He told me that he did it for publicity value,” wrote Canaan. “In fact, in a hospital in the New Hebrides he personally showed me the Associated Press clipping about firing more rounds than any gunner in one day….I believe on the day he fired them, the Jap planes at Rabaul were all dead.” Canaan advised the newspaper to check McCarthy’s “official jacket in Washington.” It would, he thought, “expose the guy for the fraud he is.”

The Capital-Times didn’t pursue the tip, but other reporters got wind of it and started their own inquiries. Before long the real story of McCarthy’s Pacific exploits had emerged. In 1943 his squadron was assigned to Henderson Field, Guadalcanal. The work varied—from routine “spotting” flights on New Georgia, the largest of the Solomon Islands, to bombing runs over the island of New Britain in western New Guinea. Sometimes, to ease the boredom, the pilots would try to break every flight record on the books—most missions in a day, most ammunition expended, and the like. According to one marine, “Everyone at the base who could possibly do so went along for the ride on some of these missions—it was hot, dusty, and dull on the ground, and a ride in an SBD [“Scout Bomber Douglas”] was cool and a break in the monotony. It was also quite safe—there weren’t any Jap planes or anti-aircraft gunners around.”

McCarthy wanted to break the record for most ammo used in a single mission. So he was strapped into a tail-gunner’s seat, sent aloft, and allowed to blast away at the coconut trees. As a matter of routine, the public relations officer gave him the record and wrote up a press release for the Wisconsin papers. A few weeks later, McCarthy came into the fellow’s hut waving a stack of clippings. “This is worth 50,000 votes to me,” he said with a smile. The two men then had a drink to celebrate the creation of “Tail-Gunner Joe.”

All told, McCarthy made about a dozen flights in the tail-gunner’s seat. He strafed deserted airfields, hit some fuel dumps, and came under enemy fire at least once. His buddies recalled that he “loved to shoot the guns.” They gave him an award for destroying the island’s plant life, and they laughed hysterically when he lost control of the twin 30s and pumped bullets through the tail of his plane.

It was on one of these missions that McCarthy claimed to have been wounded in action. Later, in his Senate campaigns, he would walk with a limp, saying that his plane had crash-landed or that he carried “ten pounds of shrapnel” in his leg. When pressed for details, he would refer to a citation from Admiral Chester Nimitz, the commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet: “Although suffering from a severe leg injury, [Captain McCarthy] refused to be hospitalized and continued to carry out his duties as an intelligence officer in a highly efficient manner. His courageous devotion to duty was in keeping with the highest traditions of the naval service.”

Citations like this were easy to come by. In McCarthy’s case, he apparently wrote it himself, forged his commanding officer’s signature, and sent it on to Nimitz, who signed thousands of such documents during the war. What bothered some newsmen was that McCarthy had never been awarded a Purple Heart. Could it be that his wound was not war related? “Maybe he fell off a bar stool,” mused Robert Fleming, the Milwaukee Journal’s crack reporter, as he began piecing together the incident. Fleming soon discovered that McCarthy had been aboard the seaplane tender Chandeleur on the day the injury occurred. It was June 22, 1943, and the Chandeleur’s crew was holding a “shellback” initiation as the ship crossed the equator. During the hazing, McCarthy was forced to attach an iron bucket to one foot and run the gantlet of paddle-wielding sailors. He slipped, fell down a stairwell, and suffered three fractures of the metatarsal (middle foot) bone. That was the extent of his “war” wounds.

It is not unusual for someone, particularly a politician, to exaggerate his war record. Nor is it the sort of falsehood that generally hurts the feelings or the reputations of others. Why, then, the controversy over “Tail-Gunner Joe”? The question can be answered in several ways. For one thing, McCarthy’s puffed-up gallantry was not an isolated instance of deception, but rather an example of the way he consistently misrepresented his actions. For another, McCarthy used his war record to shameless advantage. He thought nothing of attacking political opponents as cowardly slackers or of claiming the exclusive right to speak for veterans with disabilities and for “dead heroes.” Finally, like some compulsive braggarts, McCarthy seemed increasingly unable to differentiate fact from fancy. He lied so often and so boldly about his exploits that he himself came to accept their veracity. His friends insisted that McCarthy always stuck by his war record, even in private. When Urban Van Susteren once asked about the wound, McCarthy rolled up his pants, exposed a nasty scar, and growled, “There, you son of a bitch, now let’s hear no more about it.”

It would be an understatement to say that McCarthy launched his campaign for the Republican nomination for the U.S. Senate in 1944 as a long shot. He was, after all, a political novice residing some 9,000 miles from Wisconsin and running against an incumbent. And his hastily fashioned campaign platform consisted of two vaguely worded statements about “job security for every man and woman” and “lasting peace throughout the world.” Still, the very thought of a two-fisted marine running for political office was both novel and patriotic.

But there was a complication. According to Wisconsin law, judges can “hold no office of public trust, except a judicial office, during the term for which they are elected.” Was McCarthy violating the law? The secretary of state thought so, but the attorney general took a more liberal approach. McCarthy could run, he decided, and the courts could untangle the mess if he happened to win. Of course, McCarthy did not expect to win. He was in the race for the experience, the publicity, and the chance to position himself for a serious run in 1946. With the campaign in high gear, he got a 30-day leave and returned to a hero’s welcome. “When Joe set foot on Main Street this morning,” wrote the Shawano Evening Leader, “he did not have to walk far to find a friend. It was ‘Hello, Joe,’ left and right, to the young judge who left a seat on the bench…to take another…behind the rear guns of a dive bomber.”

On returning to the Pacific, he applied for another leave, claiming that his judicial duties had been too long overlooked. When it was denied, he resigned his commission, obtaining his official discharge in February 1945. While the war was far from over, the “fighting judge” had other things on his mind. A major national election was only a year away, with another Senate seat up for grabs. That it belonged to Robert M. La Follette Jr., a figure of heroic proportions, meant little to McCarthy. Less than a month after his discharge he was busily preparing to challenge La Follette in the GOP Senate primary.

Stalwarts of the GOP establishment in Wisconsin may not have liked McCarthy, but they thought he was the best bet to defeat La Follette. They therefore made every resource available to him, including a public relations firm, a campaign staff, and a big budget. The Committee to Elect Joe McCarthy spent more than $75,000 during the race. The La Follette figure was about $13,000. For McCarthy, money became the great equalizer.

Much of it was used to produce a slick brochure (“The Newspapers Say”) with pages of photographs and short favorable quips from the local press. The reader learned that McCarthy was a man with small-town, working-class roots; a self-made man, free of inherited wealth and privilege; a robust man who had been a farmer, a boxer, a tough marine gunner. It was an exceptional piece of campaign literature, emphasizing the very qualities that set him apart from La Follette. McCarthy loved the brochure. He told Van Susteren that most people “vote with their emotions, not with their minds. Show them a picture and they’ll never read.”

Much of the literature played strictly on McCarthy’s war record. Combat veterans have always done well at the polls, and 1946 was a fine year for patriotic chest-thumping. His newspaper ads were misleading but effective. They explained how he turned down a soft job exempt from military duty; how he joined the marines as a private; how he and millions of other Joes kept Wisconsin from speaking Japanese. And they all ended the same way: “Today Joe McCarthy is home. He wants to serve America in the Senate. Yes, folks, congress needs a tailgunner.”

McCarthy then zeroed in on La Follette’s failure to enlist. (The senator, 46 years old when Pearl Harbor was bombed, remained in Washington with virtually all his congressional colleagues.) “What, other than draw fat rations, did La Follette do for the war effort?” asked one campaign flyer. Another called La Follette a war profiteer, a charge that McCarthy pressed with great relish. The senator, it seemed, had invested in a Milwaukee radio station and was rewarded with a $47,000 profit during 1944–45. Noting that the Federal Communications Commission licensed the station, McCarthy alleged that La Follette had made “huge profits from dealing with a federal agency which exists by virtue of his vote.”

The charge was absurd. All stations are licensed by the FCC. While McCarthy didn’t try to prove that collusion occurred, his claims awakened liberal voters to the fact that La Follette had made a financial killing on a limited investment. His image as the archenemy of privilege had begun to wear thin.

McCarthy said little about his own campaign platform. He supported veterans’ pensions and the creation of an all-volunteer army—issues he knew to be popular with returning veterans and their families. His speeches on foreign affairs were laced with generalities that appealed to both isolationists and internationalists. His main theme was that America had the duty either to lead the world or to play no part in it at all. He never said which alternative he favored.

McCarthy edged La Follette by 5,000 votes. A few months later he won the general election as part of a GOP landslide that gave Republicans control of Congress for the first time in 18 years.

As a freshman U.S. senator, McCarthy was known mainly for his raucous behavior. Angry colleagues accused him of lying, of manipulating figures, and of disregarding the Senate’s most cherished traditions. By 1950 his political career was in deep trouble. He was up for reelection in 1952, and most political analysts expected him to lose. He felt that he needed an issue to attract attention—something to make his importance felt beyond the walls of the Senate chamber.

On February 9, 1950, during a routine dinner speech before a women’s Republican club in Wheeling, West Virginia, McCarthy declared that he held a list of 205 communists actively shaping policy in the State Department. Overnight, his notoriety grew a thousandfold.

Although McCarthy had hardly “discovered” the political exploitability of communist infiltration, he was uniquely gifted in using it to promote himself publicly. He convinced an increasingly frightened America that the Reds and their fellow travelers had orchestrated a conspiracy so immense that he—and he alone—could be trusted to deliver the nation from it.

But soon McCarthy’s life would rapidly disintegrate. In February 1954 the Senate had authorized his investigation by a vote of 85–1. Eight months later it had condemned him by a vote of 67–22. And eight months after that it would crush his spirit—and what remained of his career—by voting, 77–4, to censure him.

In the interval between his famous Wheeling speech in 1950 and his official Senate censure some four years later, McCarthy lost his identity as a man to that of an “ism,” his name touted by his enemies as a symbol of political opportunism, coercion, and reckless accusation. McCarthyism is still a dirty word in the American political vocabulary.

Although the censure had humiliated McCarthy, his physical decline had been obvious for years. In the latter part of 1956 McCarthy was treated at the Bethesda Naval Hospital for a variety of ailments: hepatitis, cirrhosis, delirium tremens, and the removal of a fatty tumor from his leg. Between visits, his friends pleaded with him to stop drinking, but to no avail. “I would scream at him,” Van Susteren recalled. “I’d say, ‘You’re killing yourself, Goddamit.’ And he’d say, “Kiss my ass, Van.’ And that was that.”

McCarthy entered Bethesda again on April 28, 1958. He died on May 2. The official cause of death was listed as acute hepatitis—or inflammation of the liver. There was no mention of cirrhosis or delirium tremens, though the press hinted, correctly, that he drank himself to death.

David M. Oshinsky, a Pulitzer Prize–winning historian, is a professor of history at New York University and the director of the Division of Medical Humanities at NYU Langone Health. He is the author of A Conspiracy So Immense: The World of Joe McCarthy (Free Press, 1983), from which this article is adapted.

[hr]

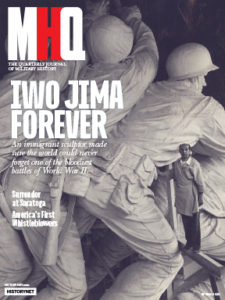

This article appears in the Spring 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: War Stories | The Tail Gunner

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!