Tactical success in combat rests upon a foundation of deeply human factors, and the battles of the Civil War were no exception. While scholars continue to tirelessly probe the letters and diaries of “common soldiers” hunting for evidence of their convictions on a wide range of topics, few have examined how the beliefs members of particular regiments collectively held about themselves, their unit, and the tasks they were assigned could influence their performance on the battlefield.

The operational history of the war has long been written mostly in narrative, chronicling the movements of regiments and brigades as if they were chess pieces pushed around by generals. Decisions of commanders are critically analyzed and their relative competence weighed against that of their opponents. But warfare is conducted by groups, not merely individuals, and is best analyzed through that lens. Civil War soldiers experienced battle as members of specific regiments and batteries, and the ways in which they and their comrades perceived events in battle and behaved under fire as a unit were powerfully informed by their past experiences as members of their particular unit. The assorted lessons and beliefs imparted by those experiences formed an important part of each unit’s culture. Every tattered regimental banner on a Civil War battlefield represented a distinctive story, a cohort with an individual personality, character, and culture borne of all the trials and tribulations, and successes and failures that had led it to that specific place in time and space.

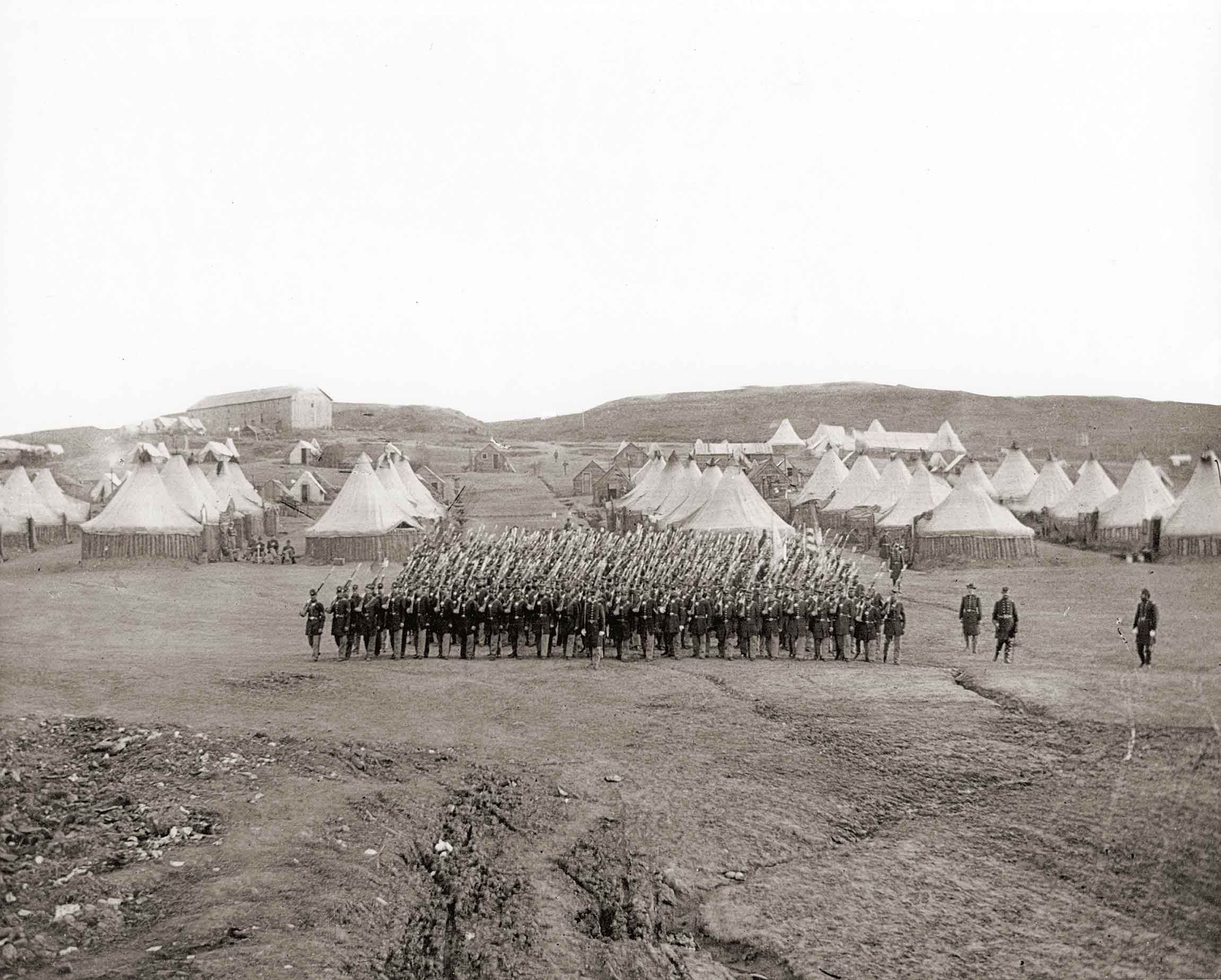

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he regiments of Union Brig. Gen. Charles Hovey’s brigade offer a case study of how regimental cultures formed and impacted combat performance. His new brigade of Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele’s 1st Division of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 15th Army Corps, Army of the Tennessee, was formed just weeks prior to the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou in late December 1862. The brigade of six infantry regiments and one battery was cobbled together from units garrisoning Helena, Ark., in preparation for Sherman’s first attempt to capture Vicksburg. They included two regiments of newly raised Iowa troops, the 25th and 31st, along with four “old” regiments, the German-majority 3rd, 12th, and 17th Missouri, and the 76th Ohio. While the latter four had all been in uniform since the first spring of the war, only the latter three had yet seen action in any meaningful sense. Hovey himself had earned his brigadier’s star for gallantry while leading an Illinois regiment through a Rebel ambush in Arkansas as a colonel, but was by no means a combat-hardened commander.

The prewar college president, however, was a quick study. Ordered by Steele on December 26 to probe cautiously down a heavily wooded and narrow levee with his brigade at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou northwest of Vicksburg, Hovey adeptly rotated out his green Iowans and placed the more experienced Missourians in the front of his column. Sherman ordered Steele to attempt to turn the Confederate forces ensconced atop Walnut Hills guarding the only road south into Vicksburg, and Hovey’s brigade was charged with spearheading this effort. Very quickly, his attention to the different levels of combat experience within each of his regiments paid off.

When the head of the brigade was suddenly ambushed, the Missouri veterans took it in stride, dispersing to find cover and returning fire. Having survived similar brushes with enemy fire before at the Battle of Pea Ridge, the Germans were steeled by their past experiences of survival and success. Even so, this time the Rebels proved unwilling to budge, and most of Hovey’s brigade eventually withdrew without ever firing a shot.

Although the rookie Iowans had been mercifully spared from danger, while they huddled around small fires in the Yazoo River bottoms that evening under a torrential downpour, survivors of other less fortunate Hawkeye regiments that had been heavily engaged in Sherman’s main assault on Walnut Hills mingled with the still-green recruits. The shell-shocked survivors “came around and told us how near they had come to being almost annihilated during the day and had barely escaped,” one green Hawkeye wrote. The horrific stories they told of terrible losses in the attack, along with the apparent incompetence of “our Generals,” made a deep impact on the impressionable recruits, negatively shaping their outlook on bayonet assaults and threatening their trust in both Sherman and Steele. “We wondered why…our Generals were only competent to lead single regiments into ambuscades and between cross fires of artillery thereby destroying the army and accomplishing nothing,” a frightened Iowan pondered.

The influence of these horror stories first became evident when the brigade received orders from Steele to prepare for a nighttime attack on the heavily fortified Rebel works north of Vicksburg at Drumgould’s Bluffs on New Year’s Eve. After being ferried northward by steamers under the cover of darkness, the division was to land and storm the enemy works at bayonet point. Those in the ranks were warned that any who failed to maintain their forward momentum would be shot on sight. Privates were “instructed that the danger was as great in the rear as from the front, and that the heights must be taken if every man should fall,” one shocked Hawkeye revealed. The receipt of such foreboding orders within the context of the horror stories they had just recently overheard was too much for many to take. “Many officers quailed before such a prospect,” one Iowan recalled. “Every man whose bowels did not overcome his bravery,” another wrote, “supposed that he had said his last prayer.” Even the veteran German officers of the 12th Missouri “brooded about what was going to become of us” while they “braced themselves up with whisky and steadied ‘file closers’ by the same means.” Fortunately, the attack plans were aborted when fog precluded all visibility of the objective.

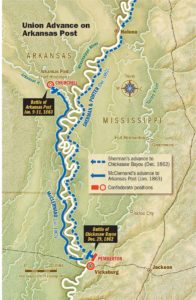

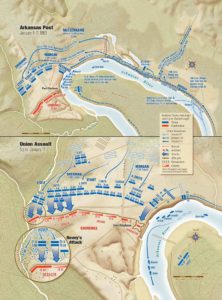

Two weeks later, on the morning of January 11 at the Battle of Arkansas Post, Steele ordered Hovey to form his brigade in preparation for an army-wide frontal assault against fewer than 5,000 Confederates who held hastily dug entrenchments protecting the vulnerable flank of Fort Hindman on the Arkansas River. The secessionists were vastly outnumbered by the 30,000-man Federal host with which Maj. Gen. John McClernand hoped to overwhelm the meager garrison. When McClernand’s initial plans to envelop the fort and force its bloodless capitulation were stymied by a combination of swampy terrain and Rebel opposition, only a direct assault seemed likely to decide the question. As Steele’s aide informed Hovey of the forthcoming assault, it fell to him to organize and arrange the regiments of his brigade in a manner that would best facilitate their success.

Hovey’s deployment decisions once again needed to be informed by the distinctive history, capabilities, and culture of each unit, not merely the relative experience of their commanding officers. Awaiting orders from the cover of a forest on Hovey’s right, Colonel Francis Hassendeubel’s veteran 17th Missouri, comprised principally of German amateur gymnasts from Turnverein athletic clubs across the Northern states, would constitute the tip of Hovey’s spear. Hassendeubel had earned an impressive record of valor both in Mexico and earlier in the Civil War, and had secured a reputation as a sound tactician and courageous leader. His “Turner” veterans prided themselves on athleticism and marksmanship, and the regiment quickly became Steele’s dedicated light infantry force, earning it the informal cognomen of “Hassendeubel’s sharpshooters.”

As the veteran 12th Missouri was detached to guard the brigade’s supplies at the transports, the 17th was one of only two units in Hovey’s brigade on the field that had ever conducted a charge, having successfully assaulted a wavering Secessionist line at the Battle of Pea Ridge, on March 8, 1862. More recently, several of the German companies had engaged in a brief skirmish with Texas Rangers in Arkansas that left several of their beloved comrades dead. The night after that fight, word spread that most of the casualties had been slaughtered in cold blood after surrendering and begging for mercy. The rumors deepened the anti-Rebel convictions of the free soil “Dutch,” and they thirsted for revenge.

Behind the 17th, Hovey deployed Colonel Isaac Shepard’s 3rd Missouri. Bay State native Shepard had never personally seen combat, but had led men in a prewar Boston militia before moving west to Missouri. That experience had netted him a position as Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon’s aide-de-camp at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, but a kick from the general’s horse incapacitated him just prior to the fight. Like their commander, most of Shepard’s men filling the 3rd Missouri’s ranks had never experienced combat. Previously assigned to counter-guerrilla duties in Missouri, they had conducted long marches and chased bushwhackers from countless hideouts in the brush, but the ultimate crucible of battle had thus far evaded them.

Fortunately, the veteran 17th would shield Shepard’s unblooded command from the impending storm of Rebel fire when the brigade approached the enemy works. The 3rd, in turn, would shield the even greener “fresh levies” of Colonel William Smyth’s 31st Iowa following in support. Smyth, a portly Irish lawyer, and his cohort represented the fruits of Lincoln’s most recent call for volunteers. Under arms for less than six months, the regiment was barely more than a crowd of civilians with elementary instruction in drill, having yet had no opportunity to test their collective mettle. Even Smyth still had trouble remembering the proper commands on the parade field, occasionally having to embarrassingly rely on a low-toned inquiry to his adjutant: “Lieutenant, what shall I say?”

Smyth’s Hawkeyes looked upon the band of “old” Germans arrayed to their front as hardened veterans by comparison. Focusing on following their lead would ease the terror of forthcoming events while presenting opportunities to learn from observation. Still, in the interest of everyone’s safety, Hovey ordered Smyth’s greenhorns not to fix bayonets or affix caps to their loaded rifles, but rather to follow closely behind Shepard’s line until further orders. This both signaled to the nervous Iowans that they would not be expected to engage in any hand-to-hand fighting and prevented their spontaneous firing against orders.

Formed to the left of these regiments, in the open beyond the timber, were the 76th Ohio and 25th Iowa. As with his arrangements on the right, Hovey placed the only other combat-experienced regiment in his brigade, the veteran Ohioans, ahead of the “new” Iowans following closely in support. At the signal of the field batteries, Hovey’s brigade launched into action.

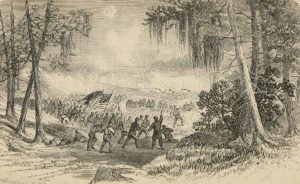

As the Ohioans and Hawkeyes on the left rushed ahead at the double-quick through the open field to their front with wild cheers, the trees and underbrush of the timber made it difficult for the right wing to keep pace. Rebel batteries began to blindly plunge shellfire into the trees. Fragments from one bursting shell tore into Hovey’s hand, distracting him briefly from command. As the rounds cracked through the canopy, the Westerners instinctively laid down in the brush for cover, further slowing their advance. One Iowan took note of how “trees and stumps were much sought for and those who had been in service before and honored for their bravery were among the first to seek them.”

As the two left wing regiments of the brigade continued to surge ahead, the 76th and 25th quickly found themselves alone, mostly out of sight or reach of either Hovey or the rest of the brigade. They would fight a separate engagement as a result. Though originally planning for the weight of his entire brigade to strike the Confederate works at once, the vexing terrain had robbed Hovey of his plans. Things only got worse. As the right wing crawled through the timber, sporadic enfilading fire through the trees from the right suddenly spelled danger to Hassendeubel’s Germans.

First Taste of Hard War

William T. Sherman’s and John McClernand’s expeditionary flotilla on the Mississippi River during the winter of 1862-63, the opening movements in the effort to capture Vicksburg, have received little attention from military historians of the Civil War. That is unfortunate given that the battles of Chickasaw Bayou (December 26-29, 1862) and Arkansas Post (January 9-11, 1863) featured many aspects of fighting now commonly considered to be typical of operations during the final year of the war: sustained periods of close contact and intense fighting, increased employment of skirmishing tactics, and regular recourse to earthworks.

All of those factors were integral components of the fighting in the Mississippi and Arkansas bottomlands in the winter of 1862-63. The labyrinthine prewar levee system planters had erected to control the fickle rivers proved ideal impromptu earthworks, introducing many regiments to the challenges of overcoming a fortified enemy position for the first time while simultaneously impressing upon them the value of digging in to provide similar protection.

“It does very well for men at home to turn up [their] nose at ditches and picks and spades,” one Iowa officer reflected, “but to a man brought up before cannon and sharp shooters they become a good institution.” After spending a week skirmishing and sharpshooting while in close contact with Rebel defenders along Chickasaw Bayou, many in the Federal ranks complained of “nervous strain and sleepless exposure.” Frequent rains and the lack of cover on steamer transports meant that many went for weeks with hardly any opportunity to dry their soaked uniforms and equipment.

Many subsequently froze while maneuvering at night on land where blankets and other creature comforts were frequently prohibited. Though small compared to months-long operations like the Atlanta Campaign, several soldiers who served in both perceived relatively little difference.

Reflecting on his experiences at Chickasaw Bayou after the war, Private Charles Willison of the 76th Ohio, a veteran of the most trying portions of the Atlanta Campaign, maintained that “no engagement in which I was afterward involved impressed me with the nightmarish sensation of this one.”

On the Civil War home front, many recoiled from newspaper accounts of grotesquely high casualty figures, equating the severity of particular fights with their respective “butcher’s bills,” just as historians often do today. Soldiers enduring the clashes, however, were restricted to what path-breaking historian John Keegan called their limited “personal angle of vision” when evaluating their own experiences. Comparatively small engagments could be as traumatic and impactful to participants as major, titanic engagements.

When soldiers read those same newspaper accounts published by embedded correspondents, even if they included portions of the official reports of generals, they often found that their personal experiences of an event, and those of their unit, were difficult to situate within the emerging big picture. As Keegan pointed out in his classic 1976 book The Face of Battle, the big picture did not reflect the myriad individual experiences that unfolded at the ground level.

But it was those experiences of a particular event at the ground level that soldiers and their regiments reflected upon and learned from. Historians still tend to think in terms of narratives wherein all the movements of even the smallest of actions are understood.

Such a reality was alien to the soldiers fighting through the smoke. Fully understanding the influence such experiences had on the maturation of the Civil War soldiers and units that fought and endured them requires a quest to reconstruct the many “faces of battle.” –E.M.B.

Spying a handful of Texas cavalrymen—their archenemies—the Turner skirmishers quickly changed front to address the new threat and removed the protective coverage of their veteran experience from the brigade’s assault. Piling into a ravine for cover, the 17th’s veterans began to ply their trade, even as the rest of Hovey’s formation, now with Shepard’s untested 3rd Missouri in the lead, debouched from the trees into the open and approached the still silent Rebel pits.

Civil war frontal assaults were almost entirely contingent upon psychology. Success relied on an attacking regiment’s task coordination and psychological resiliency. Commanders provided inspiration and guided their formation, junior officers repeated commands to the men above the din, sergeants maintained discipline from behind the ranks, and privates relied on confidence in their leaders, each other, and their perceived probabilities of survival. Above all else, a regiment needed to collectively believe it could successfully make (and survive) an attack in order to maximize its likelihood of doing so. This became especially important once the terrifying effects of enemy fire began to dramatically challenge the supposition. The capacity of a point-blank defensive volley to rob an assaulting unit of its belief in success and survival lay at the heart of defensive tactics.

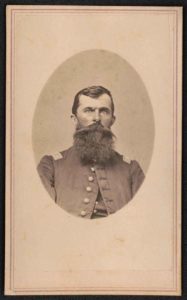

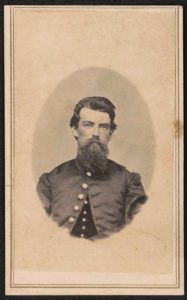

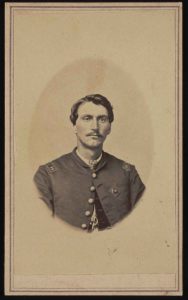

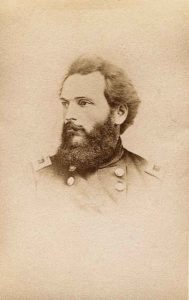

Hawkeye Leaders: The officers above all served in the 31st Iowa Infantry, and on their shoulders fell the responsibility to lead the regiment through its harrowing initial battles at Chickasaw Bayou and Arkansas Post.

All members of an attacking regiment had to sustain their confidence in success while maintaining forward momentum through the traumatic crucible of a defender’s initial volley. It was during the reception of this “shock” volley that a unit’s particular past experience and culture could make all the difference, either steeling the souls of the men or inspiring existential dread and premonitions of imminent disaster. If a regiment could psychologically withstand the terror of the initial blast of gunfire, the odds of a defender abandoning his position were relatively high. Rarely were attacking regiments physically destroyed by a single volley, and in most cases no hand-to-hand fighting would ensue. Bayonet charges functioned more as psychological weapons than as tools of physical coercion in Civil War battles, but contrary to popular belief frequently proved effective.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Frontal assaults were almost entirely contingent upon psychology[/quote]

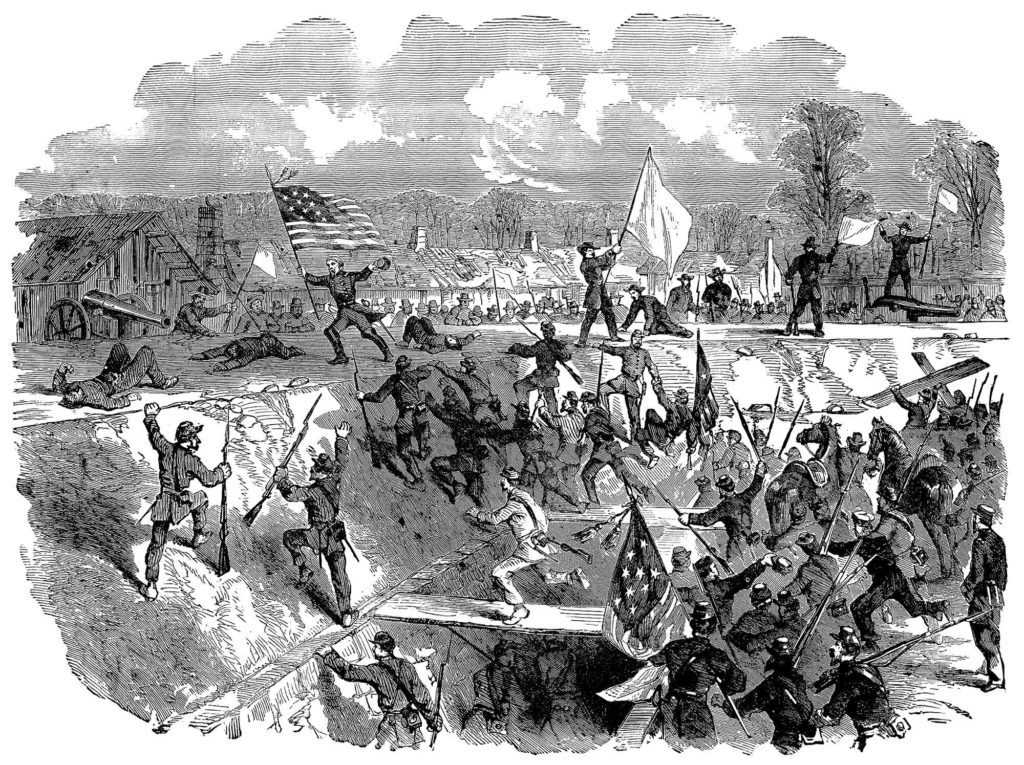

Hovey’s right wing was less than 100 paces from the Rebel earthworks when the “blue beans flew into our ranks, bringing death and destruction,” the 3rd Missouri color-bearer recalled. Unlike the errant veteran Ohioans to their left, who successfully endured two successive Rebel volleys before hitting the ground for cover upon realizing they were unsupported, nothing in the 3rd Missouri’s heritage had prepared it for such an experience. The Germans were cut down mercilessly by fire from the front and flanks as they struggled to climb over felled trees meant to slow their advance.

“It was impossible to get over the barricade,” the ensign recalled. “We were all crowded into trap, and our boys fell like flies. It was terrible.” In a matter of minutes, 75 Missourians were struck by Rebel fire, and 14 of them killed. Still, the regiment had not been physically obliterated. Even given the casualties it had sustained, along with the Hawkeyes following up close in support, Hovey’s right wing still vastly outnumbered the Rebels in the pits. Far more effectual than the human carnage the volley had produced was the confusion and terror it sowed among the Missourians.

The terrified Iowans following closely to the rear looked on in horror. Though spared the physical effects of the Confederate fire, the sight of the long-service veterans to the front as they “staggered and fell to the ground” immediately inspired shock. “Someone in their line cried that the order was retreat,” an Iowan recalled. Accordingly, the survivors “sprang to their feet and with the rapidity of lightning, dashed back upon us.” The result was chaos, and although only 14 Iowans had yet been wounded, the Hawkeyes spontaneously joined the rout. Seizing the national colors, Smyth cried for his shaken regiment to re-form, but with only moderate success. Those steadied began to fire from the cover of the trees, but none dared take another step forward. Hovey’s brigade had learned its lesson.

Despite Hovey’s repulse, after the survivors engaged in a close-range firefight from the safety of the trees for several hours the Confederate garrison of Fort Hindman spontaneously surrendered and the Battle of Arkansas Post ended in Union victory. Initially aghast at how their obvious failure to overwhelm the Southern defenders had somehow ended in victory, the men of Hovey’s brigade eventually congratulated each other on their survival and success. Even so, when once again aboard the damp decks of frigid steamers and later crowded around countless campfires in the Louisiana mud of Young’s Point, the more complicated cultural legacy of Arkansas Post was etched into the fabric of the culture of each regiment in Hovey’s command.

Despite the larger battle ending victoriously, the trauma of the brigade’s own repulse deeply influenced the confidence of the men in each unit in their collective ability to succeed in any future assault. Gazing across the Mississippi at the Vicksburg defenses from their miserable camps along the Louisiana bank, the survivors of “the Post” dreaded the future.

Most hoped their leaders had learned the same lessons they had from the terrifying experience. “Our Officers have found that Storming rebel Breast works with Infantry does not pay,” one Iowan wrote. “It is discouraging…to always have to attack an enemy behind his entrenchments,” another Hawkeye considered. “I hope that it will not have to be done here.” Such a lack of confidence could prove the Achilles heel of any future attack.

This became starkly evident when the brigade was next called upon to charge Rebel earthworks during the Siege of Vicksburg on May 22, 1863, when Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant ordered a major assault to try to break the Southern lines. Other brigades along the 15th Corps line, many having enjoyed prior success in assaults, struggled through the fire all the way to the enemy parapet—at least until their formations were dismantled by Confederate fire—the regiments of Hovey’s brigade, now led by Colonel Charles R. Woods, showed little of the resolve they had before Arkansas Post, halting their advance well short of the Rebel parapet at the first available cover.

It was not only the intensity of Rebel fire holding the brigade back, but also the traumatic heritage of each regiment in the brigade. The experience only reinforced the assumptions maintained throughout the brigade about their inability to succeed in frontal assaults. “I do not think there will be any more charges made,” one Iowan officer concluded afterward. “The men cannot be made to do it.”

Battle Rattle

Battle of Chickasaw Bayou

December 26-29,1862

In this opening effort to capture Vicksburg, Miss., Union forces attacked the city from the northwest, but were thwarted by a combination of miserable weather, thick woods, bottomless swamps, and stout Confederate resistance.

U.S. Forces

Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman

15th Corps, Army of the Tennessee

Mississippi River Squadron

31,000 men, 1,800 casualties

C.S. Forces

Lt. Gen. John Pemberton

Dept. of Mississippi and East Louisiana

14,000 men, 200 casualties

Battle of Arkansas Post

January 9-11,1863

Union forces were successful in capturing Fort Hindman at Arkansas Post on the Arkansas River, which prevented Southern forces from using the waterway as a means to disrupt activity on the Mississippi. Overall commander Ulysses S. Grant, however, was not informed of the movement, and considered it a distraction from the primary goal of capturing Vicksburg.

U.S. Forces

Maj. Gen. John McClernand

Army of the Mississippi

28,949 men, 1,061 casualties

C.S. Forces

Brig. Gen. Thomas Churchill

Fort Hindman Garrison

4,900 men, all killed, wounded, or captured

Indeed, the only regiment of the brigade that proved willing to press home its attack that day, with disastrous consequences, was the 12th Missouri, which had been detached guarding transports during the Arkansas Post fighting. Left unsupported by the reluctant remainder of the brigade, the Missourians suffered more than 30 percent casualties during the assault. Now, they too shared in the convictions of the rest. “Sherman thinks that everything can be forced by the stormers,” one disgusted officer observed. After successive traumatic repulses, the men of the brigade emphatically disagreed.

While unique in their particulars, Hovey’s regiments were not at all singular in their learned aversion to frontal assaults. The same pattern of erosion of effectiveness when called upon to charge is a phenomenon historians have long identified as a trend in both armies during the war, most especially during its later years. Crucially, however, due to the lack of any formal “lessons learned” program in either army, every Civil War regiment developed such an aversion along its own unique trajectory or “learning curve.”

Historians have long recognized that it mattered who commanded an army or unit at a particular time and place in military history. They have proved far less attuned to the often finely nuanced differences between tightly bonded groups of combatants on the battlefield, and the impress of all past experiences they collectively carried with them and brought to bear in their struggles against the enemy. Exploring such dynamics offers plentiful opportunities to advance the operational history of the Civil War in new and widely interdisciplinary directions, aiding in the ongoing quest of crafting far more holistic explanations for the performance of military units and the outcomes of both minor engagements and major campaigns.

Eric Michael Burke (@xv40rds) is a Ph.D. candidate in military history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His current project, “Soldiers From Experience,” analyzes the evolution of operational heritage and culture in the regiments of Sherman’s 15th Army Corps during the Civil War. His broader research explores the many ways in which historical experience shapes how military organizations past and present operate on and off the battlefield. He is a U.S. Army combat infantry veteran; 1/9 Infantry, 2nd ID in Iraq and 1/12 Infantry, 4th ID in Afghanistan.