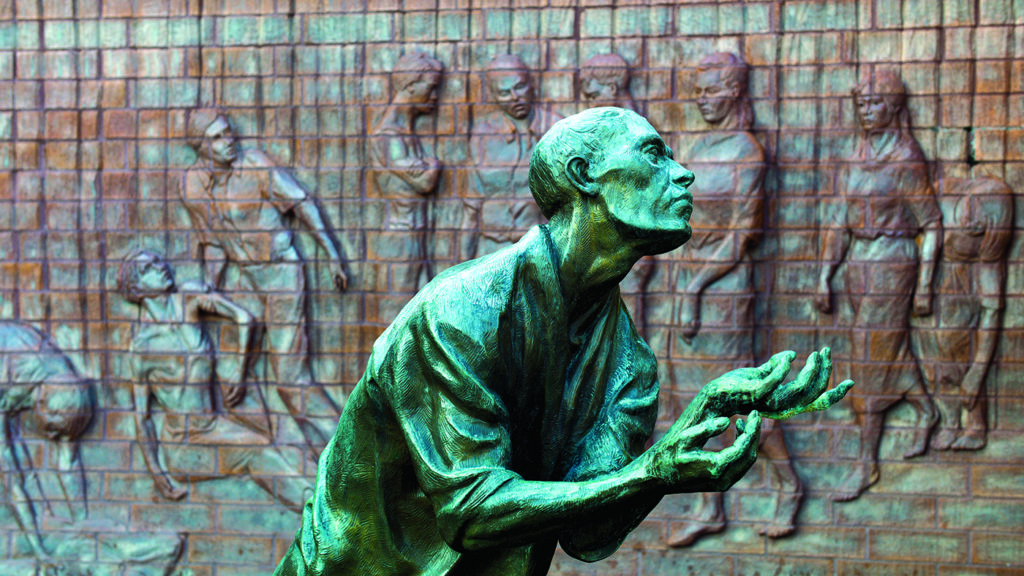

As the conflict went on, conditions for captives became more and more inhumane

“Wuld that I was an artist & had the material to paint this camp & all its horors.” Union Sergeant David Kennedy so described Camp Sumter near Andersonville, Ga. A Confederate soldier, however, could have spoken similarly about Union prison camps, as both sides failed to adequately house and feed their prisoners. Approximately 211,000 Union soldiers were captured during the war, and some 30,000 died in their prison pens. Meanwhile, 215,000 Confederates were held in Union camps, and some 26,000 died while incarcerated. Prison deaths had been curbed early in the war due to the 1862 prisoner exchanges outlined by the Dix-Hill Cartel, but after it collapsed in 1863, for a number of reasons, including the South’s refusal to swap black soldiers, the number of men who perished in prison rose. When Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant canceled all exchanges in 1864, overcrowding worsened and the death toll soared. The prison systems of both sides suffered under the inadequate leadership of officers unprepared for the tremendous task at hand. The Union’s Colonel William Hoffman was frugal to a fault and refused to implement numerous prison reforms because of cost. Confederate Brig. Gen. John Winder demonstrated a callous indifference to captive suffering on multiple occasions. Bad food, insufficient shelter and clothing, and cruel guards were the lament of prisoners Blue and Gray. “God help the sick or the weak, as they were literally left out in the cold,” remembered a Virginia prisoner. There were more than 150 prisons established during the war. Following are a few of those sites you can visit, pause, and pay homage to those captives who later returned home and those who did not.

[hr]

CONFEDERATE PRISONS

Camp Sumter, Ga., better known as Andersonville, was established in February 1864. A simple stockade with no shelter, the overcrowded prison held 33,000 inmates at its August 1864 peak, and was the Confederacy’s 5th largest “city” at the time. The prison’s fiendish prisoner gangs, cruel guards, 13,000 deaths, and controversial commandant Henry Wirz have provided dark grist for many books. The National Park Service interprets the reconstruction of the notorious prison and a memorial and a museum for all American prisoners of war is located there.

A converted harbor fort in secession’s heart, Castle Pinckney was located on a small island in Charleston Harbor, S.C. The fort was too small to hold many captives, and it only served as a prison in 1861. Its Union prisoners, roughly 160 men from New York and Michigan captured during the First Battle of Bull Run, established the “Castle Pinckney Brotherhood,” to determine civil rules of conduct among the inmates. The prison is a ruin today, and is one location that is not easily accessible.

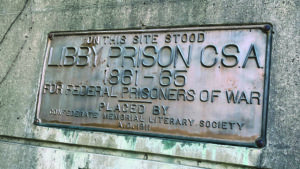

A symbol of the prison system’s make-do nature, Richmond’s Libby Prison was a converted tobacco warehouse along the James River, one of several in the Confederate capital used for such a purpose. Libby held up to 1,200 Union officers, and in early February 1864, 120 of them decided they had had enough. With kitchen implements and a wooden box, they worked for 30 days to dig an escape tunnel, but only 59 men made it to freedom. The prison was dismantled and sent to the Chicago World’s Fair in 1889, then sold piece by piece as souvenirs. Today, a plaque at 2000 E. Cary St. indicates the prison’s site.

The deteriorating conditions of the prison camp at Salisbury, N.C., an abandoned cotton factory, were indicative of those facing most of the war’s prisons. The first Union prisoners arrived here in December 1862, with a population of 1,500 inmates. By fall 1864, however, 10,000 miserable men filled the quarters and murderous gangs ravaged the population. From that time until April 1865, more than 3,000 men died. The guards, boys and old men, had no better rations than the prisoners. The Salisbury National Cemetery administers the graves of wartime prisoners and the individual resting places of modern-day veterans. The cemetery also contains monuments dedicated to Union prisoners, one erected in 1908 by the state of Maine, the 1875 Federal Monument to the Unknown Dead, and the 1909 Pennsylvania Monument.

[hr]

Island inmates

Johnson’s Island held a number of prominent Rebel generals within its walls, including

Brig. Gen. James J. Archer

Brig. Gen. William Beall

Brig. Gen. William L. Cabell

Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson

Maj. Gen. John S. Marmaduke

Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith

Brig. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson

Maj. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble

[hr]

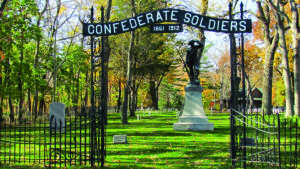

UNION PRISONS

Modern-day Johnson’s Island pre-sents interesting contrasts. Extravagant homes now stand adjacent to the Confederate prisoners’ cemetery. As you wander among the tombstones of those who died far from home, the whir of speedboats buzzing around Lake Erie’s Sandusky Bay breaks the silence and park rides can be spotted in the distance at Cedar Point Amusement Park. The prison was built on its namesake island to house captured Confederate officers. It held more than 3,000 officers at peak population. Harsh winters proved insufferable for inmates. The Johnson’s Island Preservation Society maintains and offers tours of the POW cemetery, which holds more than 200 graves.

The North’s answer to Andersonville was Elmira, a 30-acre stockade with barracks established in July 1864 along the Chemung River in New York. The river often flooded the camp, and a stagnant, festering lagoon fouled with human sewage was at the center of the prison. The green-lumber barracks warped and offered little resistance to cold winds. Nearly 3,000 of the 12,147 men sent to the camp died in its year of existence. So brutal were the conditions, that when the post surgeon on one occasion wrote, “the number of deaths this week was but forty,” it was with a sense of relief. The Friends of Elmira Prison maintains a website and museum about the prison.

Prisoners nicknamed the commandant of the Fort Delaware prison, Brig. Gen. Albin Schoepf, “General Terror,” a fitting nickname for the man in charge of this cage of horrors built on the quaintly named Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River. “A respectable hog would have turned up his nose at it,” was the way an Alabamian described Fort Delaware. Damp, cold winters were a hallmark of the prison, where, in 1863, 8,000 inmates languished in miserable conditions. They looked like “the vanguard of the Resurrection…thin faces and wasted forms,” one observer wrote. The fort is now part of a Dela-ware State Park and is interpreted to 1864. Demonstrations include the firing of a 32-pounder cannon.

Point Lookout State Park in St. Mary’s County, Md., preserves portions of the Point Lookout prison, including some original earthworks, a recreated portion of the stockade wall, and some guard barracks buildings, frequently the site of living history programs. Point Lookout was considered a depot prison, where prisoners were sent temporarily for processing to other camps and were housed in tents. If a prison location can be beautiful, this site is, bounded by the wide, tidal Potomac River and the Chesapeake Bay. Wicked winter winds, however, swept over those waters to freeze the inmates in their flimsy tents. A cruel irony haunted Old Dominion prisoners who could see Virginia on the Potomac’s west shore. Tensions ran high between the prisoners and their U.S. Colored Troops guards.

More recognizably associated with the War of 1812 and “bombs bursting in air,” Fort McHenry, an NPS site, also held political prisoners during the 1861 secession crisis. After Gettysburg, 7,000 Army of Northern Virginia prisoners were shuttled to this harbor fort. In a historical twist, some of those Confederates had served in Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead’s Brigade. Lewis, who was killed at Gettysburg, was the nephew of Major George Armistead, who commanded Fort McHenry during the 1814 battle that inspired the penning of the Star-Spangled Banner.