With its manicured lawns and mature trees, Pickwick Road in Centreville, Virginia, is a nice place to raise a family. But it was once a place to fight a war. Halfway down Pickwick Road, you can park and walk along what’s called the Covered Way, a three-acre linear park that winds through the housing developments. Here, Union forces built a long series of defensive earthworks, many of which can still be seen. Befitting its name, Centreville was considered an important Northern Virginia crossroads, connecting several important towns including Manassas, Warrenton, and Washington, D.C. Throughout the war, fighting, ransacking, and bivouacking were common occurrences in Centreville and the neighboring town of Fairfax, as Union and Confederate armies crisscrossed the region, leaving damage and desolation in their wake. “If ever a village was killed in war,” a Washington, D.C., newspaper declared in 1914, “it was Centerville [sic].” But news of the town’s death was premature, as these two towns are now among the most populated suburbs of Washington, D.C. People can still view battlegrounds, field hospitals, winter quarters, plantation houses, and even two martyrs’ graves, all in a single weekend. Most sites are located about a half-hour to 45 minutes west of Washington, D.C., off Interstate 66. –Kim O’Connell

Tried by War

At the outbreak of hostilities, a clerk named Alfred Moss removed George Washington’s will from the 1799 Fairfax Court House, but inexplicably left Martha Washington’s will behind. Taken by Union Lt. Col. David Thomson, Martha’s will eventually landed in the hands of steel magnate J.P. Morgan, who refused to return it to Virginia. Eventually, Morgan’s heirs returned the will to Fairfax in 1915. The courthouse was also the site of a June 1861 fight that killed Captain John Quincy Marr, the first Confederate officer to die in a military engagement during the war, and a monument to the captain is located there. In June 1863, J.E.B. Stuart’s men whipped an outnumbered force of Union troopers at the courthouse, but the skirmish slowed the Confederate horsemen yet one more day in their effort to rejoin the Army of Northern Virginia during its advance into Pennsylvania.

Winter Quarters

Not far away from St. John’s Episcopal Church sits an undeveloped park that was the site of Confederate winter quarters, rows of small pitched-roof log buildings that together resembled a shantytown. According to published plans, the county may eventually include an interpretive trail and some reconstructed quarters at this site, but for now, it’s simply a quiet place for contemplation.

Churches in the Crosshairs

Built in 1854, Centreville’s Old Stone Church (left), a Methodist Episcopal congregation, became a hospital for Union wounded after First and Second Manassas, and would change hands several times before war’s end. Soldiers finally dismantled the property, but it was rebuilt in 1870 and currently operates as the Church of the Ascension. St. John’s Episcopal Church (right) was also used during the war. Soon after the first volleys at Manassas, Union troops reportedly vandalized the property. The church was later the site of a Confederate camp and partially burned in 1863. To one side of the church is a towering magnolia tree. Here you’ll find two headstones—one memorializing the unknown Confederate dead in the churchyard and the other marking the graves of privates Michael O’Brien and Dennis Corcoran, Louisiana Tiger Zouaves who became the first two soldiers executed by the Confederacy, for a drunken attack on a superior.

Built in 1854, Centreville’s Old Stone Church (left), a Methodist Episcopal congregation, became a hospital for Union wounded after First and Second Manassas, and would change hands several times before war’s end. Soldiers finally dismantled the property, but it was rebuilt in 1870 and currently operates as the Church of the Ascension. St. John’s Episcopal Church (right) was also used during the war. Soon after the first volleys at Manassas, Union troops reportedly vandalized the property. The church was later the site of a Confederate camp and partially burned in 1863. To one side of the church is a towering magnolia tree. Here you’ll find two headstones—one memorializing the unknown Confederate dead in the churchyard and the other marking the graves of privates Michael O’Brien and Dennis Corcoran, Louisiana Tiger Zouaves who became the first two soldiers executed by the Confederacy, for a drunken attack on a superior.

Sully Plantation

Heading from Centreville to the city of Fairfax, stop at the picturesque Sully Historic Site, the 18th century estate of Richard Bland Lee. An uncle of Robert E. Lee, Richard and his family lived at Sully from 1794 to 1811, along with more than 30 enslaved African Americans. Now run by the Fairfax County Park Authority, the site contains five extant original buildings, including the main house, and a reconstructed slave quarters. J.E.B. Stuart and his men had breakfast at Sully, which must have caused consternation for Maria Barlow, whose family was living on the property, given that the Barlows were Unionists.

[quote style=”boxed”]“…The night air was chilly to men in wet clothes. At the regimental headquarters we built a fire, and to this fire the dead body was brought. We knew by the uniform that it was a Federal officer, but we did not know his name or rank.”

-Major Washington Grice, 49th Georgia Infantry, describes seeing the body of Union Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny, killed at the Battle of Ox Hill, or Chantilly, on September 1, 1862.[/quote]

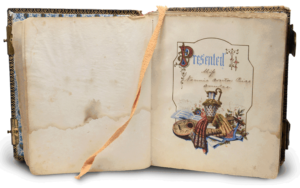

Two Horsemen

A small building that was rebuilt from the stones of a house where John Singleton Mosby met J.E.B. Stuart has now been reopened as the Stuart-Mosby Civil War Cavalry Museum. It includes several artifacts related to both of the lauded troopers, including sabers, a lock of Stuart’s hair, and a photo album, above, that Stuart gave to female friend Nannie Price. Check their website stuart-mosby.com for hours and details.

Army on the Run

Today, the paved trail through Cub Run Stream Park is popular with runners, but an interpretive sign tells the story of another famous “run”—the frenzied retreat from the First Battle of Manassas. It was here that fleeing Union troops converged on the bridge over the stream, abandoning wagons and gear as Confederate artillery rained down on them.

A Double Battlefield

The Ox Hill Battlefield Park in Fairfax is well worth your time. This is the site of both a fierce battle on September 1, 1862, as well as a historic preservation battle. In the late 1980s, a determined group of preservationists—including the late Brian C. Pohanka—worked to save the battlefield from the rapid development that was taking over the rest of Fairfax County. Today, this five-acre site remains a monument to the power of preservation activists.

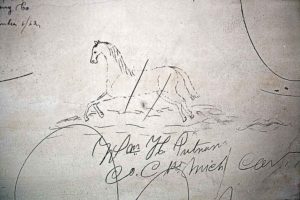

Writing on the Wall

Civil War soldiers commonly wrote graffiti on the walls of the buildings they occupied—either out of boredom, to leave their mark, or to taunt their enemies. Located only blocks from the center of Fairfax, Blenheim is a historic brick farmhouse built in 1859 that contains nearly 125 known signatures, sketches, and other commentary on the walls done by Union soldiers who camped on the property or who were hospitalized in the house. One graffito depicts the sinking morale of the common soldier: “No money. No whiskey. No friends. No rations. No peas. No beans. No pants. No patriotism.”

Another Dimension

With content light years away from the Civil War, another must-see attraction in Fairfax County is the Smithsonian’s Udvar-Hazy Air and Space Museum. It features numerous civilian and military aircraft, including the famous Enola Gay, the retired Space Shuttle Discovery, and a Lockheed SR-71 reconnaissance plane. The kids might also enjoy a visit to Cox Farms, which features year-round produce, hayrides, and other country attractions.