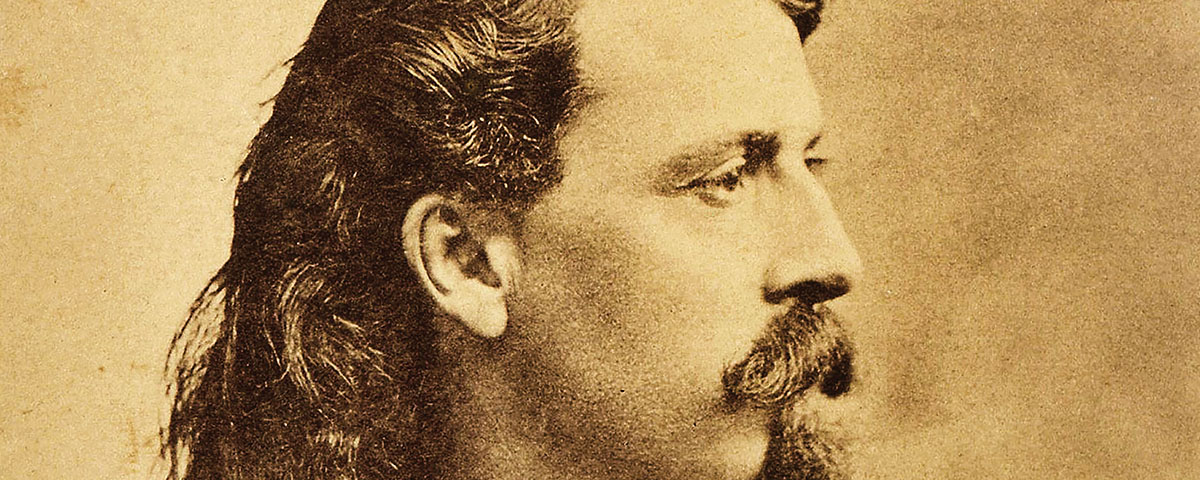

YEARS BEFORE HE WOULD BE KNOWN TO MILLIONS of Americans simply as “Buffalo Bill,” William F. Cody (1846–1917) dreamed of making a name for himself in the military. After trying unsuccessfully at the outset of the Civil War to enlist in the Union army (he was rejected as being too young), Cody went on, in the last years of the war, to serve as a scout for the 7th Kansas Cavalry. In 1868 he went to work for the U.S. Army, operating out of Fort Ellsworth, Kansas, as a civilian scout and guide for the 5th Cavalry. During the Plains Wars he fought in 16 battles, including the Cheyenne defeat at Summit Springs, Colorado, in 1869.

On April 26, 1872, Cody became one of only four civilian scouts to be awarded the Medal of Honor for valor in action during the Indian Wars. But his medal was revoked in 1917 on the grounds that he hadn’t been a regular member of the armed forces. (It was reinstated in 1989 by the Army Board for Correction of Military Records.)

In 1883 Cody created what would become Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a touring extravaganza that over the next three decades would propel him to worldwide fame.

UPON REACHING FORT McPHERSON, I FOUND that the 3rd Cavalry, commanded by General [Colonel Joseph J.] Reynolds, had arrived from Arizona, in which Territory they had been on duty for some time, and where they had acquired quite a reputation on account of their Indian fighting qualities. Shortly after my return, a small party of Indians made a dash on McPherson station, about five miles from the fort, killing two or three men and running off quite a large number of horses. Captain [Charles] Meinhold and Lieutenant [Laurin L.] Lawson with their company were ordered out to pursue and punish the Indians if possible. I was the guide of the expedition and had an assistant, T. B. Omohundro, better known as “Texas Jack,” and who was a scout at the post.

Finding the trail, I followed it for two days, although it was difficult trailing because the red-skins had taken every possible precaution to conceal their tracks. On the second day Captain Meinhold went into camp on the South fork of the Loupe, at a point where the trail was badly scattered. Six men were detailed to accompany me on a scout in search of the camp of the fugitives. We had gone but a short distance when we discovered Indians camped, not more than a mile away, with horses grazing near by. They were only a small party, and I determined to charge upon them with my six men, rather than return to the command, because I feared they would see us as we went back and then they would get away from us entirely. I asked the men if they were willing to attempt it, and they replied that they would follow me wherever I would lead them. That was the kind of spirit that pleased me, and we immediately moved forward on the enemy, getting as close to them as possible without being seen.

I finally gave the signal to charge, and we dashed into the little camp with a yell. Five Indians sprang out of a willow tepee, and greeted us with a volley, and we returned the fire. I was riding Buckskin Joe, who with a few jumps brought me up to the tepee, followed by my men. We nearly ran over the Indians who were endeavoring to reach their horses on the opposite side of the creek. Just as one was jumping the narrow stream a bullet from my old “Lucretia” overtook him. He never reached the other bank, but dropped dead in the water. Those of the Indians who were guarding the horses, seeing what was going on at the camp, came rushing to the rescue of their friends. I now counted 13 braves, but as we had already disposed of two, we had only 11 to take care of. The odds were nearly two to one against us.

WHILE THE INDIAN RE-ENFORCEMENTS WERE APPROACHING the camp I jumped the creek with Buckskin Joe to meet them, expecting our party would follow me; but as they could not induce their horses to make the leap, I was the only one who got over. I ordered the sergeant to dismount his men, leaving one to hold the horses, and come over with the rest and help me drive the Indians off. Before they could do this, two mounted warriors closed in on me and were shooting at short range. I returned their fire and had the satisfaction of seeing one of them fall from his horse. At this moment I felt blood trickling down my forehead, and hastily running my hand through my hair I discovered that I had received a scalp wound. The Indian, who had shot me, was not more than 10 yards away, and when he saw his partner tumble from his saddle he turned to run.

By this time the soldiers had crossed the creek to assist me, and were blazing away at the other Indians. Urging Buckskin Joe forward, I was soon alongside of the chap who had wounded me, when raising myself in the stirrups I shot him through the head.

The reports of our guns had been heard by Captain Meinhold, who at once started with his company up the creek to our aid, and when the remaining Indians, whom we were still fighting, saw these re-enforcements coming, they whirled their horses and fled; as their steeds were quite fresh they made their escape. However, we killed six out of the 13 Indians, and captured most of their stolen stock. Our loss was one man killed, and another—myself—slightly wounded. One of our horses was killed, and Buckskin Joe was wounded, but I didn’t discover the fact until some time afterwards, as he had been shot in the breast and showed no signs of having received a scratch of any kind. Securing the scalps of the dead Indians and other trophies we returned to the fort. MHQ

Excerpted from W. F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) and William Lightfoot Visscher, Buffalo Bill’s Own Story of His Life and Deeds (Homewood Press, 1917).

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2017 issue (Vol. 29, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: On the Trail of the Indians

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!