Thaddeus Stevens became something of a household name in 2012 thanks to Tommy Lee Jones’ memorable portrayal of the Pennsylvania congressman in the Steven Spielberg film Lincoln. As Bruce Levine makes clear in this wonderfully clear and concise biography, the club foot and the wigs were historically accurate, but there is no evidence that he had a romantic relationship with his mixed-race housekeeper.

Born in Vermont in 1792, Stevens imbibed the state’s democratic ethos and his Baptist upbringing reinforced his egalitarian impulses. Stevens graduated from Dartmouth and moved to Pennsylvania, became a lawyer, and opened an office in Gettysburg. His entry into the world of politics came with election as an Anti-Masonic candidate to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1833. He would soon join the Whig Party.

As a lawyer, Stevens took what cases he could. Although personally antislavery, he defended both those accused of being fugitive slaves as well as slaveholders seeking to reclaim their property. He also supported colonization of ex-slaves. In these ways he was not unlike a fellow Whig, Abraham Lincoln. Stevens did not start out a revolutionary; he became one.

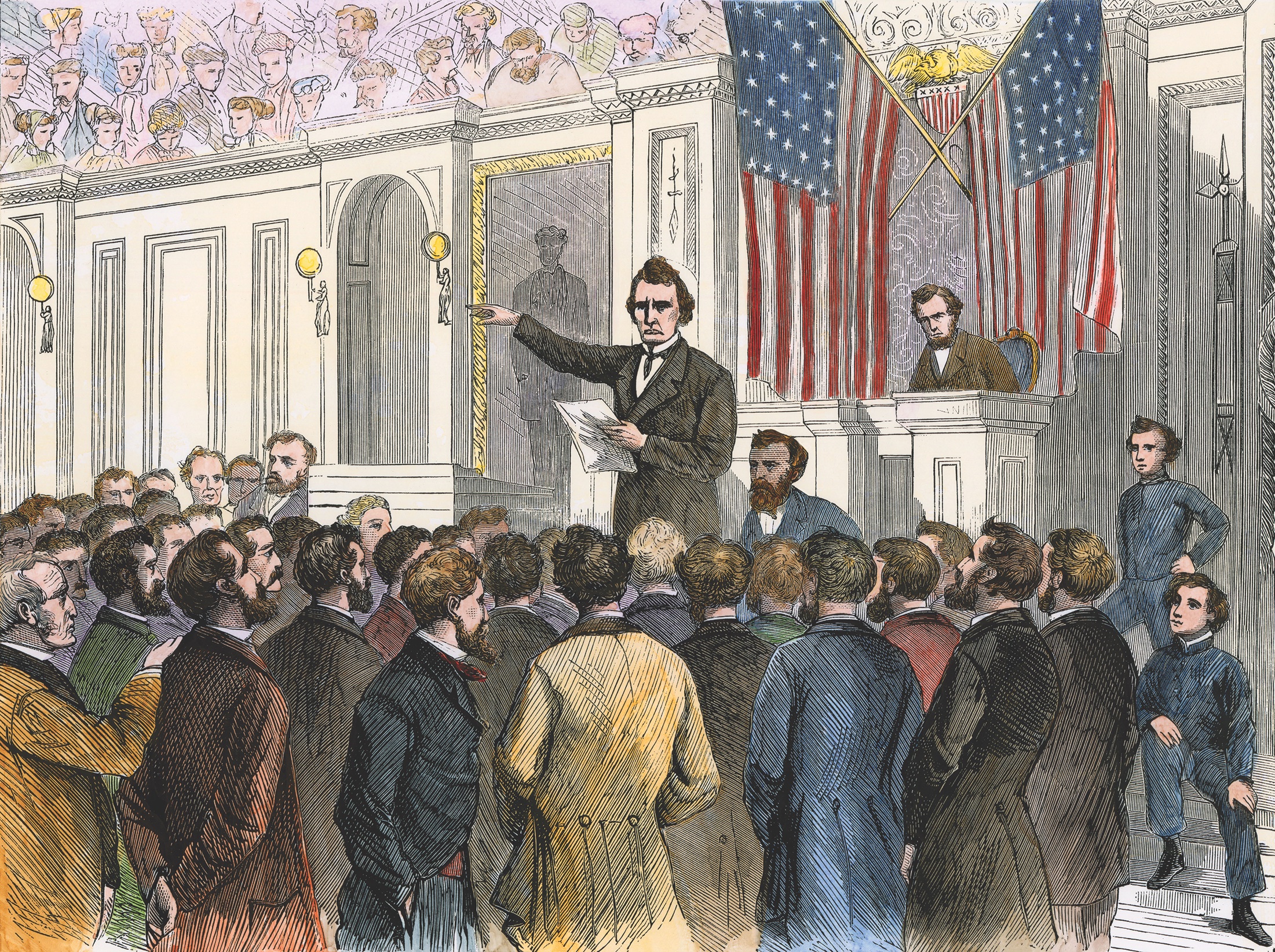

First elected to Congress in 1848, he earned a reputation, reported one newspaper, for his “witty repartee, his scorching sarcasm, his lofty eloquence, his great profundity, and his ponderous mind.” He predicted that the compromise of 1850 would become “the fruitful mother of future rebellion, disunion, and civil war.”

Stevens shared the nativist beliefs of the Know-Nothing Party and soon migrated to the newly created (1854) Republican Party. Reelected in 1858, after being out of office for five years, Stevens was 69 years old when war broke out. He assumed chairmanship of the House Ways and Means Committee and played a central role in pushing Congress and the Union toward sterner measures such as confiscation of Southern property and emancipation of Southern slaves.

By 1862, Stevens endorsed revolutionary actions “not only to end this terrible war now, but to prevent its reoccurrence.” While his advocacy on behalf of the enslaved is well known, Levine also discusses Stevens’ support for American Indians and Chinese immigrants. The one-time nativist had become a true egalitarian.

Stevens opposed Lincoln’s wartime Reconstruction measures. He also viewed congressional proposals as too timid. He disagreed that the seceded states had remained in the Union and argued that they had to be treated as conquered provinces. He believed that only by destroying the Southern planter’s economic power through land seizure would the Second American Revolution be completed.

Levine reminds us that the Radical Republicans did not dominate Congress in 1865, and that the actions of Lincoln’s successor as president, Andrew Johnson, forced moderates to tack left. Stevens himself vacillated until 1867 on support for universal black male suffrage. But he came to embrace all measures necessary to secure black civil and political rights and economic independence. He pushed for the removal of Johnson and was disappointed that the House did not frame the articles of Johnson’s impeachment more broadly.

Stevens died less than three months after Johnson’s acquittal in the Senate. He was buried in the only racially integrated cemetery in Lancaster. The inscription on his tomb reads, “I have chosen to illustrate in my death the principles which I advocated through a long life: ‘Equality of Man Before His Creator.’”