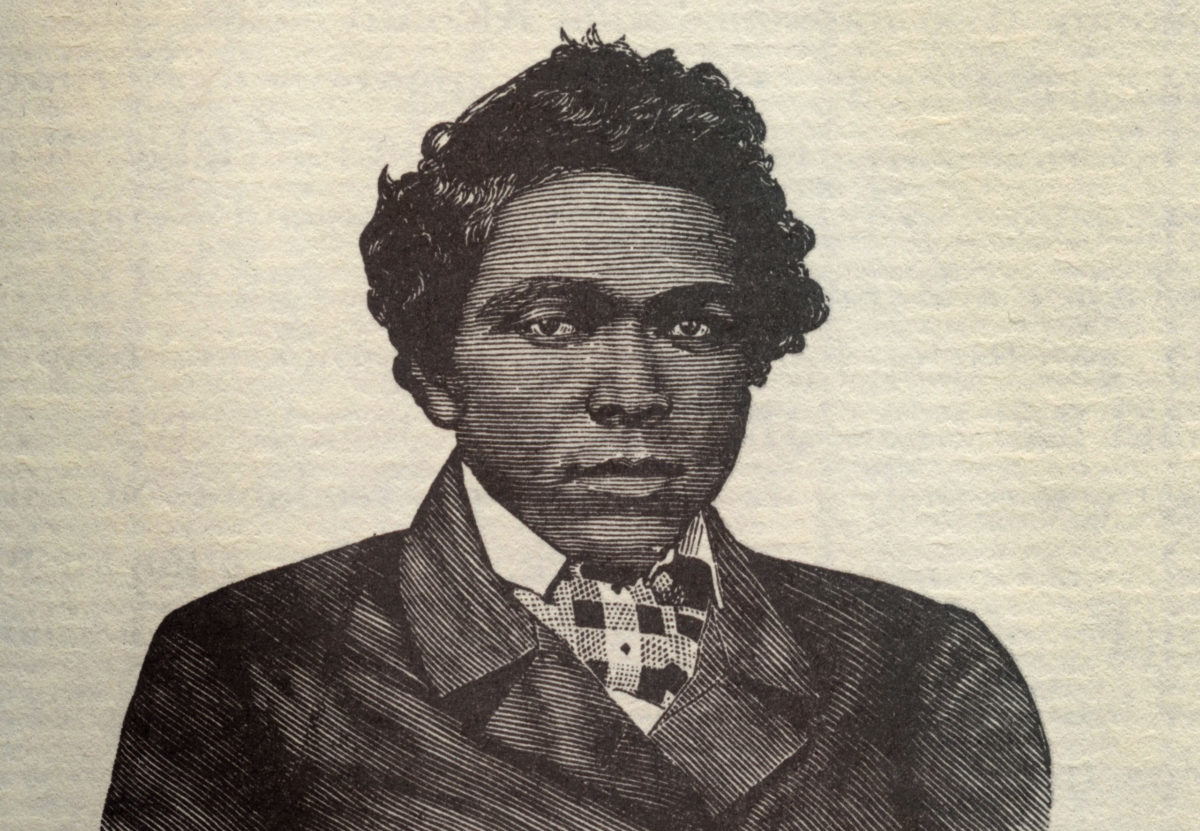

In his 33 short years of life, Abraham Galloway impacted the course of American history more than men who lived to be twice his age—beginning with his bold escape from slavery. In the span of just a little more than a decade, he risked his life as a spy for the Union Army during the Civil War, helped raise regiments of Black men fighting for the freedom of their race, campaigned for the rights of women and Blacks, and served two terms as a Republican state senator of the state into which he was born into bondage.

Galloway was born to an enslaved woman and White father on February 8, 1837, in Smithville (now Southport), a small coastal town in Brunswick County, N.C. At 11, he was apprenticed to a brick mason, and eventually became skilled at the trade. Before Galloway’s 20th birthday, his owner moved with him to Wilmington, N.C. At his earliest opportunity, the youth—along with another slave, and under the eye of a sympathetic captain—secreted himself in the cargo hold of a schooner bound for Philadelphia. From here, the abolitionist Vigilance Committee conducted him via the Underground Railroad to Canada and freedom.

In the four years prior to the Civil War, Galloway—not content to remain at liberty in Ontario (then known as “Canada West”)—traveled back across the border, establishing strong relationships with noted abolitionists. At great personal risk, he ranged from Ohio to New England giving fiery speeches.

In January 1861—just three months before the firing on Fort Sumter—the 23-year-old Galloway sailed to Haiti, along with several other militants, including Francis Merriam, a survivor of John Brown’s abortive raid on the Harpers Ferry arsenal. The group’s agenda was to recruit volunteers for a John Brown-style military invasion of the Southern states, with Haiti as their base of operations. The opening salvos of the war put an abrupt end to their efforts, though, and he sailed back to the United States, resolved to aid in the Union effort.

Galloway then put his life and liberty at risk again by volunteering to return to the slave South—as a spy for the Union Army. For the next two-and-a-half years, he reported directly to Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, and traveled surreptitiously through North Carolina, Louisiana, and Mississippi, disappearing within Black communities while gathering intelligence. All the while, he had to evade Rebel troops, slave catchers, and White civilians.

After employing Galloway as an agent during his seizure of New Orleans, Butler sent him to Vicksburg along with six companies of the 4th Wisconsin, to assess the city’s defenses. It led to his capture.

No details are known of his apprehension, or of how he regained his freedom. Certainly, if the Confederates had recognized him as a spy, they would have peremptorily hanged him, so he might well have escaped. Galloway, much debilitated from his ordeal, made his way to Union-occupied New Bern, N.C., where a former slave helped restore his health.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

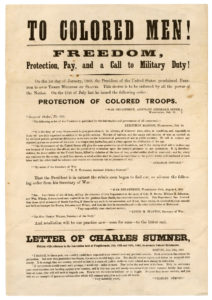

His career in espionage at an end, Galloway divided his time between creating entire regiments by recruiting African Americans from New Bern’s large Black population into the Union Army, and actively advocating for abolition. In late 1863, he traveled 75 miles outside Union lines to Rebel-held Wilmington, N.C., from which he managed to spirit his mother to New Bern and freedom. And, in the words of biographer David S. Cecelski, he also “developed a genius for politics. Among North Carolina’s freed people, he became a grassroots organizer, a coalition builder, and an inspiring orator.”

At this time, he met and married 18- or 19-year old Martha Ann Dixon, the daughter of slaves, and according to an observer, “a priceless gem among the sands of poor Beaufort.” Martha Ann shared her new husband’s burning passion for abolition and Black suffrage, and composed several fiery missives for the Anglo-African newspaper.

A powerful speaker, Galloway drew large crowds, whom he impressed with his eloquence and fervor. Commented one observer who attended one of Galloway’s orations at New Bern’s Andrew Chapel, “He handled secessionists and…Copperheads without gloves, and his speech was received with roars of laughter and great applause.”

By the spring of 1864, the war still had another year to run. On April 29, Galloway led a delegation of Black Southerners—some of them former slaves—to the nation’s capital, and into a meeting with President Abraham Lincoln. By now, there were tens of thousands of African Americans in blue uniforms, and Galloway’s priorities had grown from simply promoting Black enlistments into the Union Army. Looking to a postwar future, he broadened his scope to include unilateral Black suffrage, as well as social and political equality. To his thinking, America’s Blacks should, and eventually would, vote and hold public office.

Although Lincoln had met with Northern Black luminaries, including Frederick Douglass, during the course of the war, according to biographer Cecelski, “[T]his seems to have been his first meeting with African American leaders from the South.” The delegation presented Lincoln with a petition, urging the President, in part, “to finish the noble work you have begun, and grant unto your petitioners that greatest of privileges…to exercise the right of suffrage, which will greatly extend our sphere of usefulness, redound to your honor, and cause posterity, to the latest generation, to acknowledge their deep sense of gratitude.” The first signature on the petition was that of Abraham Galloway.

Lincoln listened respectfully to their comments, and—according to the Anglo-African—gave them “assurances of his sympathy and cooperation.” The delegation then walked to the Capitol, where they distributed copies of the petition to the congressmen.

Immediately after his visit to the White House, Galloway led members of his delegation on a tour of the Northern states, during which he took every opportunity to speak on behalf of Black suffrage.

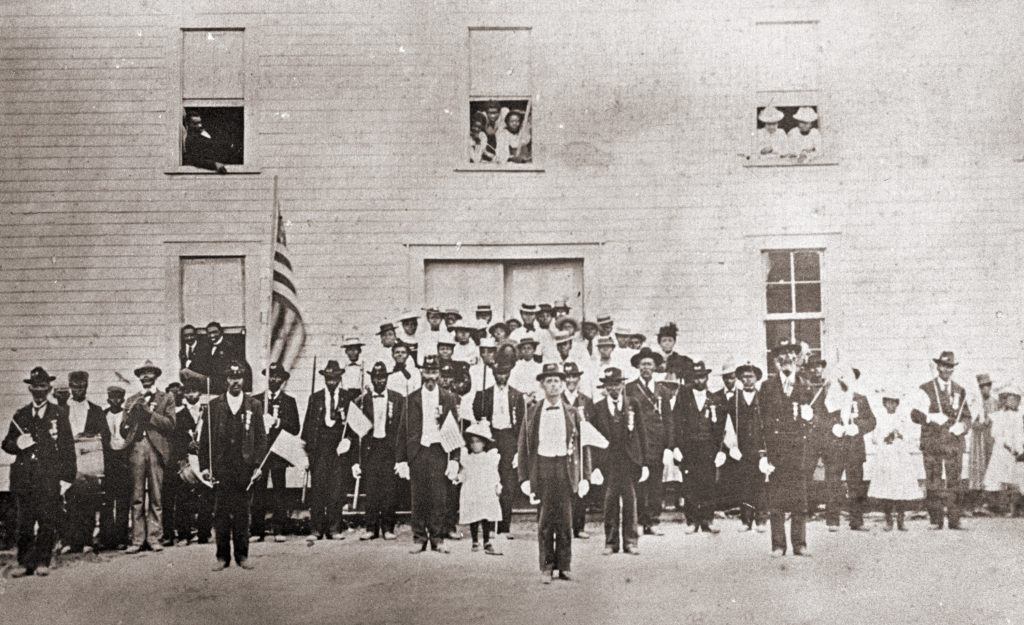

On his return to New Bern, Galloway was selected to represent North Carolina as a delegate to the National Convention of Colored Men of the United States, in Syracuse, N.Y., from which was born the National Equal Rights League. It was a powerful assemblage, and Galloway stood out as a major luminary. The Convention elected Frederick Douglass its president, and Galloway among its vice presidents. On taking office, Douglass asked Galloway to serve on the executive board.

Returning to New Bern only briefly, he spent considerable time in New York City and Boston, fundraising and addressing political functions. “He seemed to appear everywhere,” Cecelski writes, “and at any time, always active and on the run.” Then, in mid-December 1864, Abraham’s and Martha Ann’s first son, John, was born. The John Brown League, of which Galloway had become president, presented the couple with a finely engraved Bible—the first family Bible either family had owned.

Two years after the war ended, Galloway was named a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Raleigh. The following year, Abraham Galloway—former escaped slave and self-made activist for his people—became North Carolina’s first Black elector. He was twice elected to the state Senate—in 1868 and again in 1870.

Abraham Galloway died unexpectedly on September 1, 1870, just six months after the birth of a second son, Abraham Jr., and shortly following his reelection to the state Senate. Despite constant threats on his life, there was no indication of foul play; Martha Ann later revealed that he had long suffered from both rheumatism and what she referred to as “heart troubles.” More than 6,000 people attended his funeral.

Ultimately, in advocating for Black suffrage and social equality, Abraham Galloway was a civil rights leader at a time when the concept of civil rights had not yet been fully formed. Had he lived longer, history might well have ranked him alongside Frederick Douglass as one of the most influential Black men of his time. As it was, his brief political career aside, Galloway’s contribution to the Union war effort alone was extraordinary, motivated by a driving commitment to the emancipation of his people. Perhaps his self-defined mission was best defined by biographer Cecelski: “Galloway’s war had little to do with that of Grant or Lee, Vicksburg or Cold Harbor. It had nothing to do with states’ rights or preserving the Union. Galloway’s Civil War was a slave insurgency, a war of liberation that was the culmination of generations of perseverance and faith. It was, ultimately, the slaves’ Civil War.”

Ron Soodalter writes from Cold Spring, N.Y.