A Stonewall Brigade captain recounts the savage July 3, 1863, fight for Culp’s Hill at Gettysburg

When reflecting after the Civil War on the men in the “Liberty Hall Volunteers,” the nickname of Company I, 4th Virginia Infantry, William A. Anderson remembered Captain Givens Brown Strickler as being “remarkable, even among the brave men who were his comrades, for the coolness and dauntless intrepidity with which he bore himself on the field.” Strickler, like the majority of the original members of his company, had been a student at Washington College in Lexington, Va., at the outbreak of the Civil War. Enlisting as a corporal at age 21, Strickler received several promotions, and became captain of his company after the Second Battle of Manassas. He survived two wounds, one at First Manassas, where his older brother Cyrus was mortally wounded, and the second a little more than a year later at Second Manassas.

The 4th Virginia was part of the famed “Stonewall Brigade,” which, along with the 2nd, 5th, 27th, and 33rd infantry from the Old Dominion, had been raised in 1861 by General Thomas J. Jackson. The regiments had participated in all the battlefield victories achieved by “Stonewall” and Robert E. Lee in 1862 and 1863. At Gettysburg, the Stonewall Brigade was part of Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson’s Division of the Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Johnson’s Division was ordered to attack Culp’s Hill, a critical anchor of the Army of the Potomac’s right flank, in the early evening of July 2. The Stonewall Brigade was held out of that assault because it was left on Brinkerhoff’s Ridge to the east to contend with Federal cavalry.

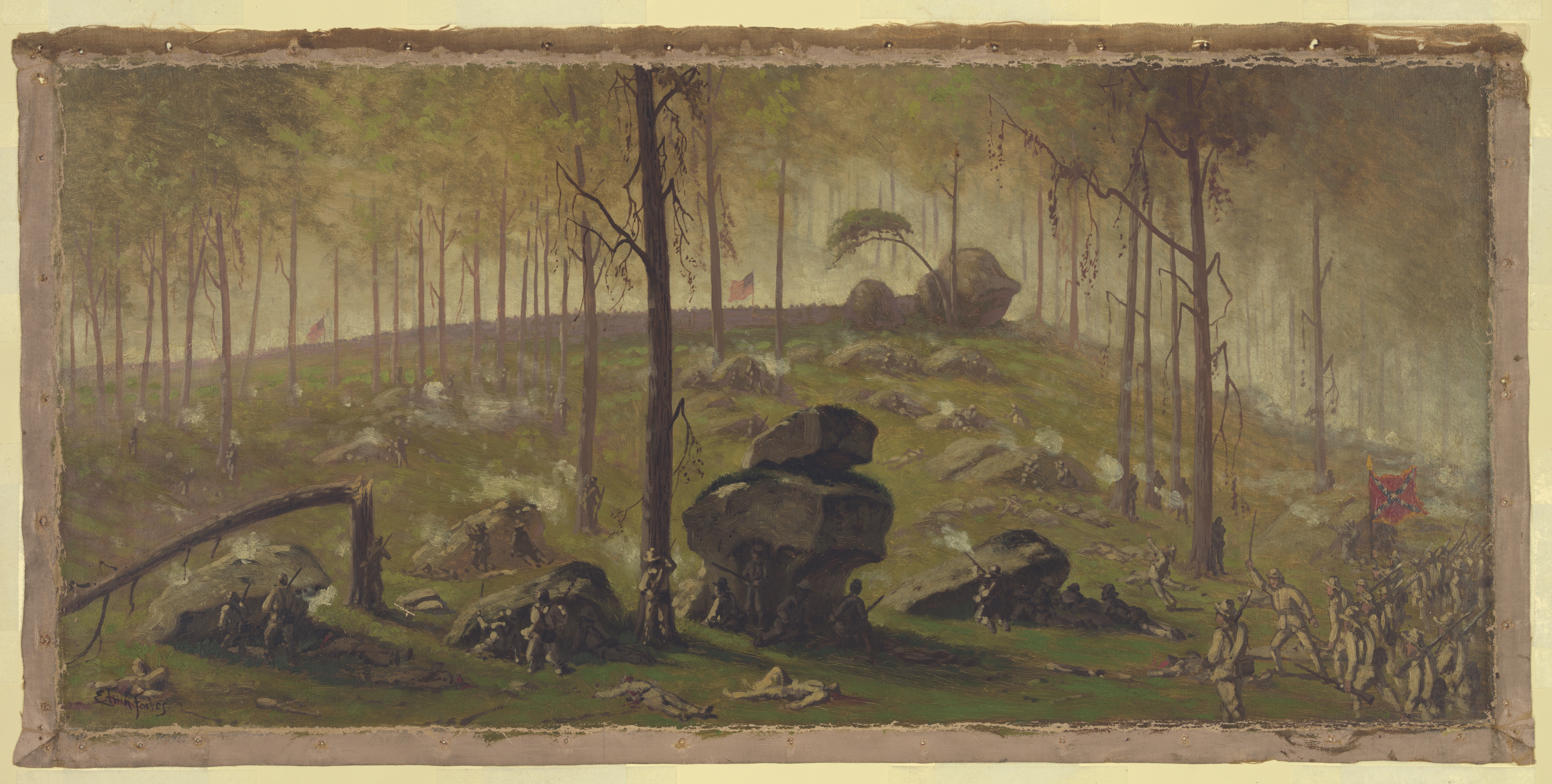

After desperate fighting, Johnson’s attacks were stalled, but fighting for the stone-studded hill would resume on the morning of July 3, when the Confederates renewed their attacks. The 4th and the rest of the Stonewall Brigade would see heavy fighting that morning when it and three other regiments of Brig. Gen. James Walker’s Brigade advanced against Federals entrenched on Culp’s Hill.

The Virginians attacked directly east up the hill and clashed with Brig. Gen. George Greene’s New York regiments—the 60th, 78th, 102nd, 149th, and 137th Infantry. Major William Terry of the 4th, reported how his men and officers received orders to relieve another regiment in the Stonewall Brigade and “advanced so far up the side of the hill under the enemy’s defenses that they afterward, when the regiments in support gave way, found it impracticable to effect a retreat.” The men were pinned down behind boulders, unable to advance or retreat on the bullet-swept slopes. Eventually, many men in the 4th were captured.

Union Maj. Gen. John W. Geary, commanding a 12th Corps division of several infantry brigades defending Culp’s Hill, offers an account of the Virginians’ subsequent surrender in his official report. Geary claimed that men of the “celebrated Stonewall Brigade” tossed down their arms and rushed into Union lines with “white flags, handkerchiefs, and even pieces of paper, in preference to meeting again the fire which was certain destruction.”

As the Virginians “threw themselves forward and crouched under our line of fire,” Geary continued, “they begged our men to spare them, and they were permitted to come into our lines.” That account has become a standard reference regarding the situation on Culp’s Hill.

It is fascinating to compare General Geary’s representation in his official report of the Stonewall Brigade soldiers surrendering—“begged our men to spare them…throwing down their arms,” etc., to the account below by Captain Strickler, who doesn’t suggest any begging for mercy, or extensive display of white flags. Does Strickler purposely ignore the behavior of some of the men in his regiment? Perhaps Strickler’s vantage point was limited? Could Geary’s comments have originated from second-hand accounts provided to him by other Federals? In any event, it would seem that the battle for Culp’s Hill could use some closer study and more research.

The “Liberty Hall Volunteers” lost 16 men captured on July 3, including Captain Strickler, along with one dead and five wounded. The 4th Virginia lost 18 dead or mortally wounded, 63 wounded, and 69 taken prisoner, the highest regimental loss in the Stonewall Brigade.

After a brief stay at Fort Delaware, Captain Strickler went to the Confederate officer’s prison at Johnson’s Island, Ohio, where he remained until being forwarded to Point Lookout, Md., for exchange in mid-March 1865. Strickler returned to Washington College after the war, graduating in 1867. He had a long and distinguished tenure as a Presbyterian minister, ending his career as a faculty member at the Union Theological Seminary in Richmond. Following his death in 1913, Strickler was buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.

It is not exactly clear when Strickler wrote his Gettysburg account; it definitely is not a postwar recollection due to its sense of immediacy. It is very possible he wrote it while imprisoned at Johnson’s Island when the events would still have been fresh in Strickler’s mind. The account excerpts appearing here are courtesy of the Washington and Lee University Special Collections. Paragraph breaks have been added to enhance readability.