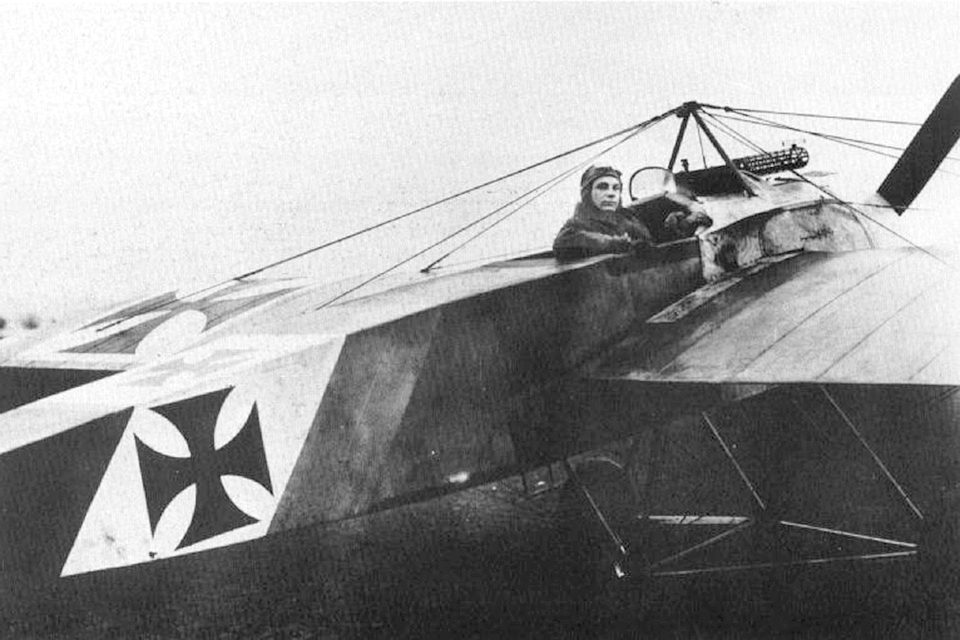

On a pale December morning in 1915 a lone Fokker Eindecker monoplane sailed high above the clouds, hunting for prey over the Vosges sector of the Western Front. Its young, inexperienced German pilot, his face greased for protection from the cold, felt snug in his thick flight suit and sheepskin-lined boots. Eyes alert, he carefully scanned the vast expanse of seemingly empty blue sky. Suddenly, a glint of silver caught the pilot’s eye, moving toward him from the west. It was the enemy.

Instead of maneuvering above and behind his opponent, the novice pilot forgot all his combat training and simply flew head-on at the oncoming aircraft. As the enemy neared, the German recognized it as a French Caudron G.IV, a queer-looking machine with a twin-boom lattice tail section and a truncated tub between the plane’s two engines carrying the pilot and observer.

As the German pilot reached for the firing button on the joystick, his mouth became dry at the prospect of his first aerial battle. The Frenchmen flew directly at him, looming so close that the observer’s head was clearly visible. The German pilot poised his thumb over the firing button, muscles tense. The moment of truth: kill or be killed.

But as the two planes came within point-blank range of each other, paralyzing fear gripped the young German and he froze. He stared at his opponent, helpless. A second later, he heard popping noises and felt his Fokker shudder. Something slapped hard against his cheek and his goggles flew off. His face was sprayed with broken glass, and blood trickled down his cheek. With the French observer still firing, the German dived into a nearby cloud and limped back to his airfield. Once his wounds had been dressed, he secluded himself in his room and spent a sleepless night berating himself for cowardice and stupidity.

Such was the inauspicious beginning of one of the most remarkable flying careers of the first half of the 20th century. The young pilot’s name was Ernst Udet, and he would later become Germany’s second-highest-scoring ace of World War I, a gifted and celebrated stunt flier between the wars and a general in Adolf Hitler’s Luftwaffe. His was a boisterous and colorful life, an adventurous span of decades that would ultimately end in tragedy.

On an April Sunday in 1896, Paula Udet gave birth to a son, Ernst. He was what the Germans call a Sonntagskind (‘Sunday’s Child’)–lucky, happy and carefree. When Udet was still a baby, his family moved to the Bavarian city of Munich, where the inhabitants loved to eat, swill mugs of beer, sing and dance–a perfect place for a Sonntagskind to grow up.

In school, Udet displayed a quick, agile mind. But his eyes glazed over when he was confronted with detail and routine. He loved to talk and got along with everyone despite a dislike of authority.

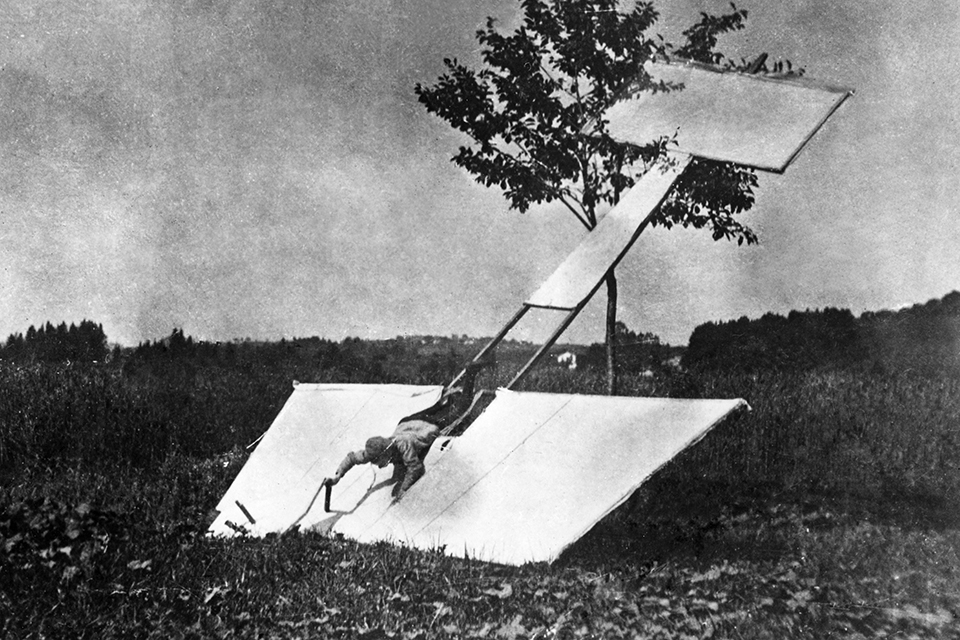

From early on Udet was fascinated with flying machines. With his school friends, he built and flew model airplanes and helped to found the Munich Aero-Club in 1909. The boys sometimes gathered around the nearby Otto Flying Machine Works to watch airplanes being built and tested, and visited an army balloon unit to gawk at training flights. Finally, Udet’s burning desire to fly drove him to construct a full-size glider with a friend. It was an ungainly contraption of bamboo and canvas, and when Udet attempted to fly it off a hilltop, he merely succeeded in smashing it to pieces. He finally got into the sky in 1913 when a test pilot working for the Otto Works took him up in a Taube monoplane. Udet was ecstatic.

But any dreams Udet may have entertained about a flying career were all but swept away by a rush of events. In July 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a Serbian nationalist, shot and killed Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo, resulting in Austria’s invasion of Serbia, which triggered World War I. On August 2, 1914, Udet tried to enlist in the army, but he was turned away because, at just over 5 feet tall, he was too short.

Undaunted, Udet decided to join the 26th Württenberg Reserve Regiment as a dispatch rider. The regiment let him in because he could furnish his own motorcycle. During his runs, Udet often rubbed elbows with pilots, which helped to respark his interest in flying. When the army ended its volunteer motorcyclist program, Udet decided to try to make it as a pilot. He paid 2,000 marks for flying lessons at the Otto Works and received his license in April 1915.

Udet was posted to Flieger Abteilung (A) 206, a two-seater artillery observation unit, where his aggressive style and eagerness for battle resulted in his quickly being promoted to Unteroffizier (staff sergeant) and transferred to Flieger Abteilung 68 (Fl. Abt. 68), flying the new Fokker E.III Eindecker fighter. Although deployed in small numbers, the E.III was at that time the deadliest airplane in the skies. It was slow and not particularly nimble, but it had one vital feature that Allied planes lacked–a machine gun synchronized to fire through the propeller. The E.III produced terror among Allied pilots out of all proportion to its capabilities, creating what was known as the ‘Fokker Scourge,’ until more advanced Allied fighters, such as the agile French Nieuport 11 and Britain’s Airco DH.2, tipped the scales in the Allies’ favor.

It was with Fl. Abt. 68 that Udet experienced his first humiliating one-on-one combat with the French Caudron. But after a period of intense soul-searching, Udet determined that he would succeed as a fighter pilot. He had his squadron’s mechanics construct a model of a French plane against which Udet could fly practice attacks, honing both his shooting and combat flying skills. The additional training soon paid off.

On March 18, 1916, Udet received a report of two French airplanes flying near Mülhausen. He climbed into the cockpit of Fokker’s latest fighter–the D.III, a biplane–and began searching for the enemy. He soon found them–not just two as reported, but 22 machines of various makes.

This time Udet kept his head, positioned himself above and behind his targets and carefully selected a victim. Then he dived to the attack, the wind humming through the bracing wires as he gave the engine full throttle. His target, a Farman F.40 bomber, grew large in his gunsight, but Udet held his fire. When he was only a few meters away, he pumped a short burst into the French plane, which began to spit fire. As he climbed, Udet watched the Farman falling, a ball of flame and smoke. To his horror, the observer tumbled out, a tiny black object hurtling earthward.

That March 18 confrontation was Udet’s first confirmed victory, sweetened by the award of the Iron Cross, First Class. The fighter flight of Fl. Abt. 68 was redesignated Kampf Einsitzer Kommando Habsheim, and on September 28 it was reorganized as Jagdstaffel 15.

Udet’s second victory was a Bréguet-Michelin bomber, brought down during a massive bombing raid on Oberndorf by French and British units, escorted by four Nieuports of the American volunteer Escadrille N.124, on October 12. He finished his score for 1916 with a Caudron G.IV on December 24.

In January 1917, Udet was promoted to Leutnant der Reserve. Then he and his squadron received the latest fighter hot off the production lines, the Albatros D.III. With its sleek and sturdy plywood fuselage, powerful 160-hp Mercedes engine and twin Spandau machine guns firing through the propeller arc, the D.III was the ultimate fighter at this stage of the war. Along with this new fighter came orders for a new home for Jasta 15 in a more active sector of the front, in the Champagne. Stationed across the lines opposite Udet’s squadron was one of the most famous French fighter squadrons of the entire war, Escadrille N.3, Les Cicognes (‘Storks’), which boasted France’s leading ace, Georges Guynemer.

The combination of a new fighter and a new posting to a part of the line offering more targets resulted in Udet’s steadily increasing his score. On February 20, he forced down a Nieuport 17 into the French lines. Its pilot, Sergeant Pierre Cazenove de Pradines of N.81, survived to eventually become a seven-victory ace. On April 24, Udet shot down a Nieuport fighter, which burst into flames after a short dogfight, and he destroyed one of the new Spad VII fighters on May 5.

Personal gain, however, came at personal loss. Six of the original pilots who had been there at the formation of Jasta 15–Udet’s closest comrades, plus the commanding officer Oberleutnant (1st Lt.) Max Reinhold–were killed either in combat or in crashes. Udet often had the sad task of sending letters of condolence to the family members. ‘I’m the last of Jagdstaffel 15,’ Udet wrote to Oberleutnant Kurt Grasshoff, a friend who was commanding officer of Jagdstaffel 37, ‘the last of those who used to be together at Habsheim. I should like to move to another front, to come to you.’ Clearly, for the 21-year-old ace, the war was becoming a grim affair.

Shortly after writing that, Udet was involved in one of the most famous air duels of World War I. While balloon hunting on a solo patrol, he watched as a small, rapidly moving dot approached him. Seconds later Udet recognized the stub nose of a Spad VII and hunched down in his seat, readying himself for a fight. The two enemy pilots dashed head-on at each other, then banked, each trying to get onto his opponent’s tail. The planes twisted and turned, neither pilot at first able to get off a good burst. Soon Udet realized that this Frenchman was no novice but a skilled pilot, for with every trick Udet tried–half loops, slip-sideslips, sharp banks–the surprising Spad stuck determinedly to him, getting off short, well-aimed bursts in the process.

During one pass, Udet glanced at his enemy and saw a pale, drawn face and the word Vieux written in black on the fuselage. Udet’s heart rose into his throat. Vieux Charles was the name given to all of Georges Guynemer’s aircraft–Udet was seemingly locked in a duel-to-the-death with the famed French pilot. Suddenly, a stream of bullets ripped into Udet’s top wing, but he cut away and after a few more turns had the French ace in his sights. Udet squeezed the firing button, but his guns remained silent. They were jammed. Frantically, he pounded them with his fist just as Guynemer flew by overhead. Guynemer came on again, almost upside down now, but instead of sending a blast of lead into his helpless opponent, he stuck out a gloved hand, waved and then disappeared to the west. To the end of his life, Udet never forgot that act of chivalry.

At the beginning of summer 1917, Udet was scoreless so far for that year, despite flying almost daily patrols. But on June 19 his long-awaited transfer came, removing him from the unit in which he had lost so many friends and moving him to Jasta 37, several miles behind the lines. This fresh location did him good, and he brought his score up to nine by the end of August. In November, more honors came to him: On the 7th, he was made commander of Jasta 37 when Grasshoff was transferred to command Jasta 38 in Macedonia, and Udet received the coveted Knight’s Cross of the Order of Hohenzollern.

Udet proved to be a good leader. He spent long hours training novice pilots in the art of air fighting and, like many successful aces, emphasized good marksmanship over flashy stunt flying. He was easygoing, boisterous and loved drinking until late at night and chasing women. He enjoyed the star status that came with being a pilot and often dressed in a dapper style, a cigarette usually poised carefully in one hand. He still displayed the disdain for authority and routine that had characterized him as a child. And he enjoyed being curt and cheeky to pompous officers, his ranking position and success as a fighter pilot usually saving him from reprimand. By year’s end, he was a 16-victory ace and a highly decorated pilot.

In early 1918, Udet was visited by a small, slim man with a delicate face and soft voice, Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen, Germany’s ace of aces–known to later generations as the ‘Red Baron.’ Richthofen, always on the lookout for bright and aggressive pilots, asked Udet if he would like to join his Jagdgeschwader I (JG.I). Without a moment’s thought Udet said, ‘Ja, Herr Rittmeister.’ The great ace shook his hand and left. In a later meeting with Richthofen, Udet learned that he was to take command of Jasta 11–Richthofen’s old command. Flabbergasted, Udet again accepted.

As Udet settled into his new post, the air service was gearing up for the German army’s last great offensive of the war. Code-named ‘Operation Michael,’ it was a desperate attempt to defeat Britain and France before the arrival en masse of the Americans, who had declared war on Germany in April 1917. Jasta 11 was equipped with the latest from the Fokker factories, the highly maneuverable, rapid-climbing triplane. Udet immediately liked this fighter, sensing that its lightning-quick turns would be indispensable in a tight dogfight.

After joining Jasta 11, Udet began flying multiple patrols daily, although he was increasingly troubled by an intense pain in his ears. Nevertheless, he pushed his victory score up to 23 before the pain became so intolerable that Richthofen ordered him to take sick leave. This time off was vital for Udet’s war-shattered nerves. Despite a doctor’s warning that he would never fly again, Udet’s ears began to improve. In addition, he received news that he had been awarded one of Germany’s highest military awards, the Ordre Pour le Mérite, generally referred to by its nickname, the ‘Blue Max.’ That honor was marred, though, by word that Richthofen had been lost in combat on April 21. Shaken by the death of the man whom he later described as ‘the greatest of soldiers’–a man many had believed was indestructible–Udet returned to the front on May 20, taking command of Jasta 4 of JG.I.

Despite the remarkable early successes of Operation Michael, which had seen German storm troopers advance up to 40 miles against the British and French, the war was still far from won. When Udet returned to his unit, the conflict was entering its last, dreadful months, which would see some of the most intense fighting of the entire war. His unit was now equipped with the formidable Fokker D.VII, the plane generally considered the finest fighter of WWI.

During the spring and early summer, Udet’s score rose to 35. The charmed life of this Sunday’s Child was again apparent when he took off on the morning of June 29 to intercept a French Bréguet two-seater, which was directing artillery fire over the lines. A few days before, in a fit of arrogance and impertinence, Udet had had his Fokker painted with a candy-striped upper wing and a red fuselage with ‘Lo’–the nickname of his girlfriend Lola Zink–written on it in big white letters. On the tail was the phrase, ‘Du doch nicht!‘ (‘Certainly not you!’), a taunt and challenge to Allied pilots.

Udet approached the Bréguet with great skill and precision. He fired at the observer, who sank into his cockpit. Now Udet casually swung around for a side shot at the helpless Bréguet, targeting the engine and pilot. Suddenly the observer sprang up and manned his machine gun, sending a blistering spray of bullets into Udet’s Fokker, slugs slamming into his machine gun and gas tank and shredding the controls. Udet reared away but soon found that his plane was crippled–it would only fly in circles. By accelerating whenever he pointed eastward, Udet slowly began working his way back to the German lines.

Suddenly the Fokker nosed down into a spin from which Udet could not pull out. He was wearing one of the new Heinecke parachutes that German pilots were just being equipped with, and he stood up in the cockpit to jump. As he did so, a rush of wind knocked him backward. But instead of tumbling into the wide-open sky, Udet to his horror realized that his parachute harness was caught on the rudder. Frantically, he struggled with the harness as the earth spun closer. With a final superhuman effort he yanked himself free and floated down into no man’s land. He quickly scrambled back to the German lines and, taking his harrowing experience in stride, was flying again that same afternoon. The next day he shot down a Spad fighter for his 36th victory.

On July 2, JG.I had its first encounter with the U.S. Army Air Service and shot down two Nieuport 28s of the 27th Aero Squadron. One of the pilots, 2nd Lt. Walter B. Wanamaker, was brought down injured by Udet, who gave him a cigarette and chatted with him until the medics arrived. On a whim, Udet cut the serial number, N6347, from the rudder of Wanamaker’s plane. When the two met again at the Cleveland Air Races on September 6, 1931, Udet returned the trophy to his former opponent. It can still be seen at the U.S. Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio.

Udet was one of the lucky ones. Hauptmann (Captain) Wilhelm Reinhard, commander of JG.I after Richthofen’s death, was killed on July 3 when the wing of a Dornier D.I parasol monoplane he was test-flying collapsed. Udet’s new commander was the 21-victory ace and Ordre Pour le Mérite recipient Oberleutnant Hermann Göring.

By this time the war was going badly for the Germans. Due to the British naval blockade, Germany was suffering from food and raw material shortages. The German air force was hampered by a lack of fuel, equipment and new recruits. The Allies, on the other hand, bolstered by Britain’s wealthy colonies and America’s industrial might, were sending ever greater numbers of airplanes into the skies. ‘The war gets tougher by the day,’ Udet wrote. ‘When one of our aircraft rises, five go up on the other side.’ If an Allied plane fell behind the German lines, it was immediately pounced upon by mechanics who would strip away its shiny brass and steel instruments.

These difficulties seemed to spur Udet on to new heights of achievement. Between July 1 and September 26, he downed 26 Allied aircraft, bringing his total to 62. During his last air battle, in which he brought down two Airco DH.9 bombers, he was hit in the thigh. He was still recovering from that wound when the war came to an end on November 11, 1918.

The pace of Udet’s life did not let up with the war’s end. He married his girlfriend Lola Zink in 1920 and continued to fly as often as he could, usually as a barnstormer and stunt flier. Eager to make money and never at a loss for new ideas, he founded the Udet-Flugzeugbau in 1922, a company that produced streamlined racers and stunt aircraft.

During the ’20s Udet flew in airshows and races, performing throughout Latin America and Europe. Given its founder’s flying skills and flair for publicity, Udet-Flugzeugbau experienced modest growth–but during that same period Udet’s flamboyant lifestyle flourished. He became a well-known womanizer and a hard drinker, a party boy who loved to dine and share a laugh with an international group of friends. He spent money as quickly as it came in. He enjoyed the company of movie stars, film producers and other public figures. Flying always remained his greatest passion, but his independent nature and disdain for routine led to the breakup of his marriage in 1923 and his leaving the company to become a professional stunt flier.

In a Germany wracked by depression and the ignominy of defeat, torn between Communists and the rising Nazi party, Udet was a bright star and a war hero. He was also an extraordinarily gifted pilot, possessing a marvelous sense of touch. One of his favorite crowd-pleasing stunts was to fly very close to the ground, dipping one wing low and snatching a handkerchief from the ground with his wingtip. He also excelled at corkscrew spins, breakneck dives and flying under bridges.

In the ’30s he made a host of flying films, low on plot but featuring thrilling footage showcasing his flying abilities. Udet filmed and flew in Africa and Greenland. In 1931 he thrilled crowds at the Cleveland National Air Races, where he met–and shared a shot of illegal booze with–America’s number one ace, Captain Eddie Rickenbacker. Udet’s U-12 Flamingo, a wood-body, slow-moving biplane, was no match for the sleek metal craft of his competitors, but the German pilot’s impressive flying skills stole the show.

This was probably the happiest time of Udet’s life. He was reeling in money. His autobiography, Mein Fliegerleben (English title: Ace of the Iron Cross), was a hit, selling more than 600,000 copies by the end of 1935. He was arguably the most famous stunt pilot of his day.

His own situation, however, contrasted sharply with the turn of events inside Germany. In 1933 Hitler had assumed dictatorial powers and ruthlessly began reorganizing the nation according to his National Socialist doctrines. Udet ignored politics and despised the Nazi party’s brutality, intolerance and authoritarianism, but he was proud to be a German and was proud of his war service. He listened with interest when Hermann Göring spoke to him of plans to rebuild Germany’s air force–which had been banned after World War I by the Versailles Treaty. In 1934, Udet taught Aviation Minister Erhard Milch to fly. And as the top pilot in the country, Udet’s opinion was considered quite significant when matters of aviation policy were discussed. It was flattering to be listened to by those in positions of authority.

In 1934 Udet made the difficult decision to join the new Luftwaffe. Whatever his misgivings about the Nazis, he realized that they had an iron grip on power in his country. Patriotism, the challenge of rebuilding the air force he had so loved, plus a sense of stability and security offered by the prospect of a normal job, all played a part in helping him make up his mind.

He was promoted rapidly from Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel) to Oberst (colonel) and then inspector of fighter and dive-bomber pilots. In the summer of 1936 Udet was pressured by Göring into becoming the head of the technical office of the Reich’s air ministry, a position of weighty organizational responsibilities. Despite his new duties, Udet, who had always shunned paper pushing, seemed able to find the time to test-fly the industry’s newest designs, such as the Messerschmit Bf-109, as well as the latest from Focke Wulf and Heinkel.

On the eve of World War II, Udet was again promoted, this time to Generalluftzeugmeister, or chief of armaments procurement. Now he was in control of more than 4,000 personnel and had to make a host of daily decisions regarding research and development, supply, financial matters, production of equipment and many other things–on the whole, a job for which he was temperamentally unsuited. When the war started, the strain of his office weighed heavily upon him.

Just before the German invasion of France, American reporter William Shirer interviewed Udet, finding him a likable fellow who ‘has proved a genius at his job.’ But Shirer was amazed that a party boy such as Udet had risen so high in the Luftwaffe hierarchy. The reporter astutely speculated that if American businessmen knew of Udet’s somewhat Bohemian life-style, ‘they would hesitate to trust him with responsibility.’

Udet was not adept at the political intrigue that characterizes all bureaucracies. Increasingly, he was outmaneuvered by his onetime friend Erhard Milch. Ambitious and scheming, Milch resented Udet’s special relationship with Göring and craved the power and prestige attendant on Udet’s job.

Nevertheless, Udet continued to reap honors from Hitler, who was most likely unaware of the interdepartmental in-fighting. On June 21, 1940, Udet was one of the few people who witnessed the French surrender to the Germans. A month later, he was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross and promoted to Generaloberst (colonel general).

But Udet apparently found little enjoyment in his new position. Friends noticed that the once jovial playboy had grown serious and thoughtful as his responsibilities increased. More and more Udet complained of sleeplessness and depression. He was also overweight, and his smoking, drinking and eating were out of control.

Milch continued to work behind Udet’s back, seeking to discredit him in Göring’s eyes. When the Luftwaffe failed to overwhelm the Royal Air Force during the Battle of Britain, Udet’s office was blamed. The invasion of Russia in June 1941 only added to the pressure on him, and he felt increasingly trapped in his job. At the end of August, Udet had a long, private talk with Göring in which he tried to resign. Göring refused, knowing that such a resignation from a top Luftwaffe official would create bad publicity.

Finally, on November 17, 1941, Ernst Udet put a pistol to his head and pulled the trigger. According to Nazi propagandists, the pilot had died heroically while testing a new aircraft. But in reality, life had simply lost all of its fun, adventure and charm for this Sunday’s Child.

This feature was originally published in the November 1999 issue of Aviation History. For more great stories subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!