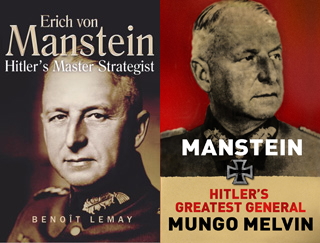

Erich von Manstein

Erich von Manstein

Hitler’s Master Strategist

By Benoit Lemay. 528 pp.

Casemate, 2010. $32.95.

Manstein

Hitler’s Greatest General

By Mungo Melvin. 672 pp.

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2010. $39.65.

It is widely agreed that Erich von Manstein was the Wehrmacht’s finest general. He was a master of strategic planning, operational command, and tactical boldness. His memoir Lost Victories is a war-literature classic. He conceived the plans that overran Western Europe in 1940, restored the German front after the Stalingrad debacle, and conducted a brilliant 10-month operational campaign against superior forces in the Ukraine in 1943–44. A master of maneuver warfare in the context of modern technology, he demonstrated his understanding of positional warfare as well during his bloody, eight-month-long conquest of the Crimea in 1941–42. But he has also been implicated in the Nazis’ mass murder of European Jews. And he argued with Adolf Hitler so forcefully and persistently that he was relieved of command in March 1944; he was never re-employed by a führer who could no longer tolerate his strong, independent personality.

But was he really a peerless commander? And just how complicit was he in his master’s war crimes? Two new comprehensive biographies, the best to appear in English, written by expert historians unknown on this side of the Atlantic, raise these issues. Benoit Lemay and Mungo Melvin work from different perspectives to present a sophisticated analysis of their tantalizing, enigmatic subject: a man both more and less than his legend. Lemay, a civilian scholar and one of the best of the rising generation of French military historians, synergizes Manstein’s campaigns and his role in the Final Solution. Retired British Major General Melvin is attuned both to Manstein’s qualities as a general and to the political dynamics of high command in the Third Reich. Both authors shed fresh light on the Eastern Front’s moral quagmire, where the Wehrmacht sank irrevocably into Nazi criminality.

Lemay describes Manstein as “the most accomplished product of the Prussian military caste of his time.” As a junior officer in World War I he acquired a thorough grasp of staff work. As a commander in the Wehrmacht he earned and kept the respect of his peers, the confidence of his subordinates, and the trust of his troops. None of these was easily achieved in the Third Reich’s combination of snake pit and hothouse, or during the constant crises of the Russian front. Melvin depicts “an accomplished bridge and chess player, always thinking several moves ahead,” remarkably successful in most of his engagements.

Lemay and Melvin agree that Manstein never addressed the wider aspects of the war he fought and the regime he served. He was overtly complicit in issuing and implementing genocidal orders, and in ignoring the spectacular crimes committed behind the fighting front. His focus was the battlefield, which Lemay says he considered “a sort of autonomous territory.” Melvin’s more nuanced perspective acknowledges the dilemma facing a senior commander confronted with not merely incompetent but illegal and immoral political direction. Neither protest nor resignation was likely to be effective. As for active resistance against Hitler, Manstein consistently rejected the option. A coup d’état, in his opinion, would bring chaos at home and collapse at the front. Both risks were alien to his heritage and his mindset.

If Manstein was a lesser man than he was a soldier, his military perspective was also less encompassing than legend claims. He never understood the limitations of operational achievements within larger strategic contexts: at Stalingrad and Kharkov, at Kursk and its aftermath, he exaggerated the impact that success in a sector had on the Eastern Front as a whole. He fell short in recognizing the comprehensive, exponential improvement of a Red Army that, by 1943, was increasingly able to overwhelm, outfight, and outthink its opposition. Above all, he failed to consider the fundamental gap between Germany’s means and ends; by 1943, that gap made the war in Russia no more than an endgame that, at best, could only delay—not avert—defeat. Masterful in crisis situations, his Prussian heritage emphasizing will and skill, Manstein was a great battle captain. But he was not a master of war.

What was the link between his limits as a person and as a soldier? Was cultivated tunnel vision a consistent characteristic, shaping his effectiveness as a planner and a commander? Lemay’s Erich von Manstein and Melvin’s Manstein: Hitler’s Greatest General combine to offer promising new ways to reconcile the gifted general with the convicted war criminal.