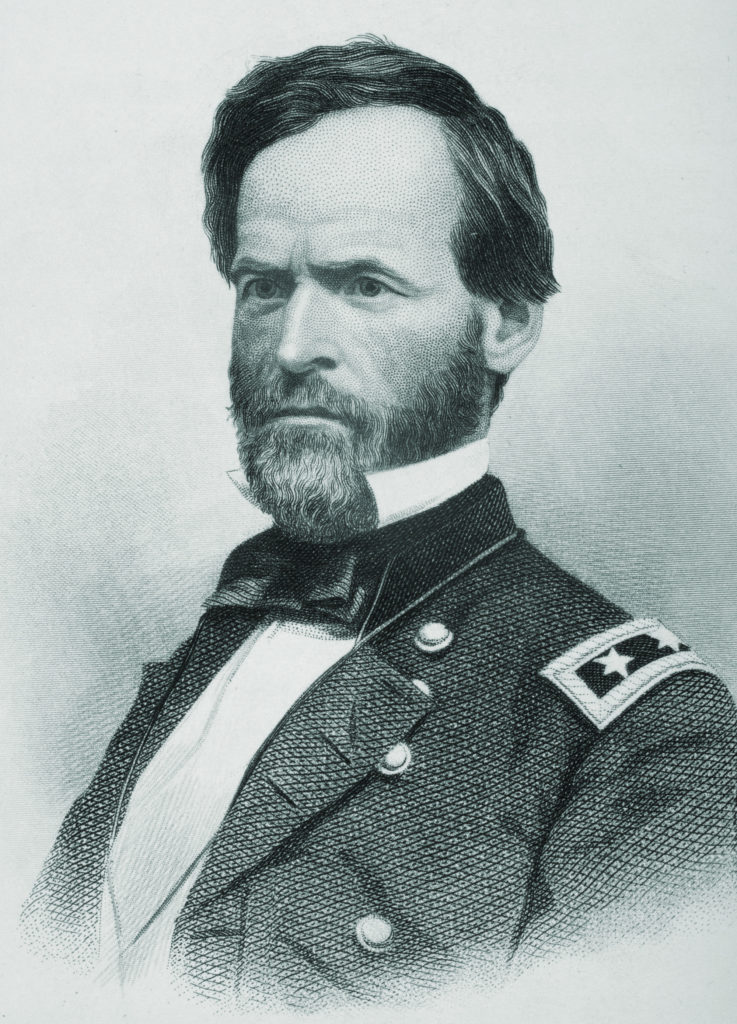

William T. Sherman’s legacy probably is linked more to 15th U.S. Army Corps than any other unit or army he would command during the Civil War. Still today, more than 160 years later, Sherman and the “Diabolical 15th” continue to spur wrath in Southern hearts and minds, particularly for the carnage wreaked during the 1864 “March to the Sea” in Georgia and the subsequent Carolinas Campaign. As Eric Michael Burke reveals, however, in his captivating new tome, Sherman’s reputation as a “hard war” commander evolved as the war progressed and, contrary to popular belief, Sherman’s men likely had a greater impact on him during that evolution than he did on them. In Soldiers From Experience (LSU Press, 2022, $50 hardcover) Burke explores new ground in analyzing the rise of corps-level tactical culture within respective Civil War volunteer armies.

What inspired your research?

Initially, my hope was (and still is) to develop new ways of effectively bridging the older, now occasionally maligned “drums and guns” literature focused on Civil War military operations with so much of the incredibly fascinating and vitally important ideas circulating in the less military-centric sub-fields of the war’s historiography. My time spent in and out of combat in the Army while serving in different units inspired an interest in me for understanding why different organizations, trained to conduct particular tasks in more or less identical ways, still tend to operate in distinctive fashions. I wanted to try to develop a more holistic understanding of why military units had such a timeless habit of developing unique collective personalities. Given the particularities of how volunteer regiments—and thus the higher commands to which they were assigned—were raised and maintained in the field during the Civil War, it was a natural place to focus that research.

Were any preconceived notions you had about Sherman impacted?

As a non-commissioned officer, I frankly found it hard to believe 19th-century generals enjoyed the degree of influence over those in the ranks they likely believed they did. That said, I think that Sherman has classically been depicted as having been far more in touch with his junior subordinates than many of his peers. I was struck to find that, while this was certainly the case later in the war, Cump truly had to grow into that role. He was never inclined toward believing some kind of special wisdom was maintained within the rank and file, and he seemed to think of himself as a consummate professional among others merely masquerading as such—and there’s some truth to that, of course—but he ultimately recognized that to be successful in pursuing his objectives he had to “speak their language” and accept their “eccentricities.”

Was Sherman’s “hard war” evolution purely the product of military necessity?

Sherman was a consummate conservative in just about every conceivable way. Politically, socially, tactically, the man was wracked with anxiety about radical change. Early on, few of his echelon in the Western Theater were as committed to ensuring that the conflict wouldn’t be transformed from a “kid-gloved” military prosecution of a mostly contained domestic insurrection into a “radical” social revolution in which America morphed from a slave society into something altogether different—which to conservatives like Sherman was, of course, frightening.

Unfortunately for Cump, he did not control events to that effect. He struggled to control the war’s political drift, struggled to control the libertine and destructive spirit of the volunteers he at least nominally “commanded,” and he very much struggled to control the trajectory of the combat engagements he prosecuted. It took considerable time and what appears to have been a nervous breakdown of sorts to finally force him to embrace the fact he would—to use his phrase—have to accept that he was “riding a whirlwind unable to guide the storm.”

Like many of his peers, Sherman grew increasingly reticent about the possibility the Southern rebellion could be terminated by relatively conservative means. By the summer of 1862, he knew only harsher policy measures would bring the most ardent secessionists to their knees, but it was important to him that such a policy be prosecuted exclusively by officers and men kept on a tight leash by professionals who knew how to ensure that “hard war” didn’t spontaneously devolve into mass destruction, rapine, murder, and such.

Tightly controlled chaos became one of his favorite strategic tools, even if it leaned too far for his liking toward the chaotic side of the spectrum.

Why do you feel Sherman’s men influenced his growth as a commander, not the other way around.

As I write, the cultures of military organizations arise organically from cycles of experience, reflection, and collective meaning-making. The experiences soldiers have are of course directly shaped by the decisions and expectations of their leaders, but a wide array of factors go into shaping a soldier’s experiences and thus his or her beliefs, assumptions, ideas, norms, etc.

Believe it or not, generals are human beings, too, which means their beliefs are likewise shaped by their experiences leading particular bodies of troops that respond to events and their own orders in particular ways. Thus, there is a perpetual cycle of mutual influence whereby commanders and their men influence each other’s behavior and thoughts, besides exogenous factors like environment or enemy action.

Historians have paid far too little attention to this dynamic and instead emphasize the individual personalities of general officers in order to explain the incredibly intricate behavior of the massively complex human systems they commanded. The truth is, it is literally impossible for a single officer to have the kind of direct unmitigated influence over the behavior of an organization as large as an army corps that they often believed they enjoyed.

Granted, the unity of command principle does mean that in an ideal situation it all comes down to one individual calling the shots. But as historians, we have to parse the difference between the legal responsibility of a final military decision and the incredibly complicated network of people, ideas, culture, and other influences that lead to shaping that individual’s decision as well as the even more complex story of how that decision is or is not actually prosecuted. Attributing it all simply to a single individual’s actions or decisions is far too easy an explanation. As a historian, I am infinitely skeptical of excessive parsimony.

Chickasaw Bayou, the corps’ first true fight, was a disaster. What did Sherman do wrong there?

Sherman’s expeditionary force failed foremost in its coordination between brigades and divisions. While that was mainly a product of the Yazoo bottomlands’ nightmarish terrain, it was exacerbated by the inattention Sherman and his staff paid to integrating each component command. Major delays in communications due to that terrain and Sherman’s habit of frustrating attempts by couriers to find him as he wandered the battlefield—mixed with major personality clashes among senior leaders—proved a toxic brew.

Given the Union advantage in numbers, a well-coordinated offense would have left the Confederates incapable of responding to all the threats Sherman could pose simultaneously. Sherman and his lieutenants also did not learn the appropriate lessons from the debacle. Instead of taking a hard look at their own coordination failures, they sought scapegoats in the inexperienced junior officer corps, whom they charged with insufficient ardor and discipline.

Though it was a Union victory, Arkansas Post saw many of the same mistakes as at Chickasaw Bayou. Was Sherman in danger of losing his men?

He was at risk of losing the confidence of his corps by the winter of 1862-63—and had already in a vast number of cases. The despondency he observed in the ranks after Arkansas Post was proof enough to him that the men of the 15th Corps were not especially happy; but, as was his habit, Sherman struggled to understand why or to what extent because he failed to empathetically observe events from their different perspective. The men lamented the loss of beloved comrades in what had been a stiff fight, but Sherman wrote off the engagement as a minor skirmish. That divergence in meaning-making in the wake of a major trauma did result in a serious deterioration of confidence between commanders and their subordinates.

Does Sherman deserve the blame he gets for the failed Union attacks at Vicksburg in May 1863?

In short, yes. Sherman and Grant failed miserably in the planning and execution of both the May 19 and 22 assaults on the works at Vicksburg. Given the strategic context, it is understandable Grant opted for an “attack by open force.” Even his decision to launch a more army-wide assault on May 22 made some practical sense.

But the coordination, and thus prosecution, of both assaults was abysmal. Everything from insufficient artillery preparation; complete failure to often coordinate attacks above the division level; inadequate attention to preparation for the myriad pioneering tasks involved in breaching a fortification like Stockade Redan; and a complete disregard for the actual psychological, emotional, and physical state of the Army of the Tennessee—these top the long list of disastrous oversights at play.

You argue battlefield terrain had a greater impact on Sherman’s tactical philosophy than weapons.

The 15th Corps fought nearly every engagement in heavily wooded, swampy, or intractably hilly and broken terrain. With the exception of the siege at Vicksburg and perhaps the fight before Atlanta on July 22, 1864, few of its actions featured viewsheds that would have allowed soldiers to visually identify targets at the actual maximum effective range of their rifle-muskets.

More often than not, the region’s broken, cluttered terrain tended to dismantle the tight cohesion of assault columns featured in most contemporary infantry commands. It was exceedingly hard, if not impossible, to send compact masses against salient enemy positions without the formations deteriorating into a “cloud of skirmishers.” Broken terrain would fragment attacking commands and inspire the men to go to ground and “sharpshoot” rather than push the charges to fruition.

Sherman is generally criticized for his November 1863 effort at Chattanooga. You give him credit. Why?

Sherman’s hesitation to launch an attack on the Rebel right at Tunnel Hill has drawn considerable fire from historians. I argue the fault belongs with Grant in failing to consider the 15th Corps’ new tactical culture in designing his operation to break out of the siege. His reticence in launching yet another failed frontal assault marks one of the first instances Sherman showed a grasp of his command’s tactical weaknesses. While some of his future actions, most notably at Kennesaw Mountain, suggest he occasionally hoped he was wrong about that conclusion, he ultimately accepted the corps was not a viable tool for frontal assaults against any but dramatically outnumbered defenders.

Will there be a second volume?

I’m interested in following the corps’ story further only if, in doing so, it shines an interesting theoretical or historiographical light on what interests me most: namely, crafting maximally holistic explanations for the tactical behavior of historical military organizations. I do not want to simply write a narrative of the latter half of the war from the limited perspective of the 15th Corps. I fervently believe that operational military historians like myself have an onus to prove “drums and guns” histories need not be abandoned as fruitful scholarship topics. But doing so requires more rigorous, more interdisciplinary, and more innovative approaches to analyzing military operations; not merely re-narrating them ad infinitum.