In keeping with the medieval tradition of warrior kings leading their armies into battle, King Edward I of England spent most of his long and turbulent reign (1272–1307) in almost constant campaigning, be it in Wales, Scotland, continental Europe or the Holy Land. In October 1297 he had just concluded a papal-brokered armistice with his archenemy, French King Philip IV, amid the Franco-Flemish War when he received shocking news: An English army had suffered a devastating defeat at the hands of Scottish pikemen at Stirling Bridge that September 11, and the victorious Scots had since mounted cross-border raids as far south as Durham. Returning to England in March 1298, Edward established his headquarters in York and set about raising ground and naval forces from every corner of his realm to subjugate the northern rebels.

Edward—dubbed “Longshanks” for his notable height of 6 feet 2 inches—had conquered Scotland in 1296 with customary brutality. The bloodbath that attended his order to sack the fortified Scottish burgh of Berwick-upon-Tweed was appalling even by medieval standards. His subsequent high-handed efforts to strip Scotland of its national identity and oversee it as an English guardianship had only provoked further unrest. By mid-1297 the violence erupted into a full-scale insurgency on either side of the River Forth, led by the highborn Sir Andrew Moray (or Murray) of Petty in the north and the lowborn William Wallace in the south.

To defray the costs of his forthcoming campaign, Edward resorted to the usual feudal methods. He issued military “writs of summons” to English and Scottish nobles, petitioned Parliament for new taxes to fund mercenaries, ordered levies of foot soldiers from Wales, pardoned criminals to help fill the ranks and ordered provisions delivered from Ireland, to which he’d inherited the lordship. It became apparent Longshanks would go to any length to raise funds. In 1290 he issued an edict expelling the entirety of England’s estimated 2,000-strong Jewish population. Under its terms he forfeited any property they left behind and transferred to his account any outstanding debts owed them. The cruel edict added considerably to his coffers.

The army Edward cobbled together at York was the largest invasion force assembled in the British Isles since Roman general Gnaeus Julius Agricola led the conquest of Britain in the 1st century. Longshanks’ army comprised 2,250 heavy cavalry and 12,900 infantry, more than half of whom were in paid service. Scarcely 2,000 of the foot soldiers were English. The rest were from interior Wales and the Welsh Marches (borderlands). Edward esteemed the Welsh in particular as the bravest, most experienced infantry under his command.

Mounted atop a magnificent black charger armored and accoutered from muzzle to hindquarters, Edward led his personal retinue across the Anglo-Scottish border, joined the assembled infantry and cavalry at Roxburgh in early July, and marched north for Edinburgh. There the king, an expert logistician, expected to meet his large convoy of supply ships en route from eastern English seaports.

As his multinational army pushed north toward central Scotland, Edward found Wallace’s scorched-earth tactics had left little forage, and his troops and horses began to suffer from the scarcity of provisions. Meanwhile, Wallace, in sole command of the Scots after Moray’s death from wounds sustained at Stirling Bridge, also marched his army north, shadowing his foe while wisely avoiding pitched battle. Unaware of the Scottish army’s location, Edward resolutely pressed ahead through Lauderdale and Dalhousie to Kirkliston, just west of Edinburgh, where he halted. Bad weather and contrary winds had dispersed the fleet carrying the vital provisions, leaving Longshanks’ troops on the verge of starvation by the time they encamped.

Though Edward’s army was impressive in scope, the rank and file were undisciplined. The Welsh archers quarreled with Gascon crossbowmen, while a number of English knights threatened to desert and join Wallace. Hoping to regroup and replenish his demoralized troops, the king fell back on the outskirts of Edinburgh, but ongoing desertions and disputes among the English knights, Gascons and Welshmen took a further toll. At one point Welsh troops engaged in a drunken riot. Though quickly quelled by English men-at-arms, the fracas cost the lives of 80 Welsh and 18 English. Edward’s 1298 campaign had essentially stalled, and the Plantagenet monarch remained oblivious to his enemy’s whereabouts.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Weighing his options from the concealed Scottish camp in Callendar Wood south of Falkirk, Wallace realized a set-piece battle against Edward’s formidable host was unacceptable. On hearing of Longshanks’ troubles, he resolved to either launch a surprise night attack on the English camp or harass the rearguard and baggage train if the factious army withdrew. On July 21, however, two traitorous Scottish earls—jealous of Wallace and eager to gain the king’s good graces—warned Edward of Wallace’s intentions and betrayed the location of the Scottish camp near Falkirk, scarcely 15 miles west of the English camp. “Thanks be to God, who hitherto has extricated me from every danger!” the period chronicles have Edward exclaiming. “They shall not need to follow me, these Scots, since I shall go forth to meet them.”

That very afternoon Edward ordered an advance on Falkirk. Though his men remained hungry and low on supplies, they likely spoiled for a fight with the enemy instead of among themselves. Led by Longshanks’ armored cavalry, the English host marched 10 miles and encamped on Burgh Muir, just east of Linlithgow. Arriving late, the army spent the night under arms. “[They] lay down to rest on the ground,” English chronicler Walter of Guisborough recorded, “arranging their shields as pillows and their arms as coverlets. Their horses, too, tasted nothing save hard steel and were tethered each one hard by his lord.” Perhaps falling asleep on night watch, Edward’s page lost control of his lord’s charger, which trod on the sleeping king, breaking two of Longshanks’ ribs and causing a commotion that roused the entire army. Cries went up they were under attack. Though calm was quickly restored, the troops remained on high alert. Seizing on their renewed spirits, Edward pushed through his pain, climbed into the saddle and led a predawn advance on Falkirk.

As sunrise approached on July 22, the English vanguard observed a body of spearmen on the heights of Redding Muir and assumed it was the main Scottish army. After rapidly forming into battle order, the English advanced upslope and crested the ridge. Finding no sign of the enemy, they halted to pitch a tent as a makeshift chapel on the banks of the Westquarter Burn. While Edward and Anthony Bek, the warrior Bishop of Durham, celebrated Mass, the morning mists cleared, and the English could clearly see the Scots massing on the crest of a ridge just south of Callendar Wood, a mile to the northwest.

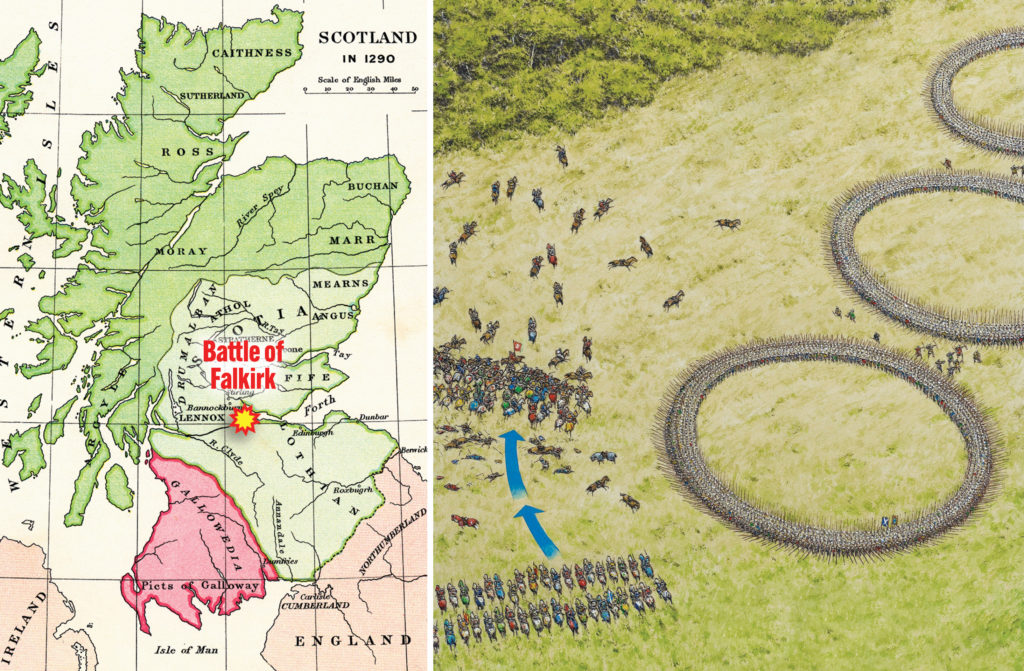

Surprised by the sudden appearance of Longshanks’ army, Wallace resolved not to risk a disorderly retreat but to fight a defensive battle in the best possible position. Callendar Wood lay to the Scottish rear, and the hillside before them sloped several hundred yards to the valley floor. Unlike at Stirling Bridge, however, Wallace found no terrain, natural or man-made, that might buttress his defenses. Convinced the English would attack from all sides, he massed his 8,000 pikemen into four huge, roughly oval formations called schiltrons. “The schiltron was a hedgehog formation of grounded spears held together with ropes staked into the ground,” historian Peter Traquair notes. “Not very maneuverable, it was the only defense foot soldiers had against the bulldozer that was a medieval mounted charge. An unmissable target for the English bowmen, the schiltron required protection by mounted troops able to drive off enemy archers.”

“In these circles the [Scottish] spearmen were settled,” Guisborough recounted, “with their lances raised obliquely, linked each one with his neighbor, and their faces turned toward the circumference of the circle.” Some accounts claim the Scots implanted log palisades to their front, but it’s doubtful Wallace had time for any such preparations.

Wallace dispersed his 1,500 bowmen under Sir John Stewart in the gaps between the four schiltrons. Trained in the Selkirk and Ettrick forests, the archers carried longbows made from yew staves that were, contrary to some accounts, equal in every way to those carried by the Welsh and English. The Scots’ chronic weakness in missile weapons was largely due to an acute shortage of men to wield them. The Scottish cavalry, scarcely 500 lances commanded by Sir John’s brother Sir James, High Steward of Scotland, likewise suffered from a crippling shortage of numbers. Committed by the Comyns and other earls who supported the rebellion but were conspicuously absent from the field, the riders comprised lesser nobles and their retinues seemingly not under Wallace’s command. They assembled on the Scottish right, beside and to the rear of that flank’s schiltron, a flawed position that invited a cavalry attack.

Thus deployed on the ridge, the Scots waited stoically for the vaunted English host. Almost the entire flower of Anglo-Norman chivalry was on hand to support Edward. But Longshanks’ gallant knights were unaware that heavy rains had turned a swath of the valley floor into a waterlogged morass wholly unsuited to mounted warfare.

After Mass, Edward coolly suggested pausing to pitch tents and feed the men and horses, none of whom had eaten since setting off the previous afternoon. According to Guisborough, his field commanders cautioned the king against such a provoking display. “This is not safe, Sire, for between these two armies there is nothing but a very small stream.” It could be the overeager knights had simply run out of patience. Perhaps sensing their zeal for combat, Edward deferred to his subordinates. After invoking the Holy Trinity, he ordered the attack.

The English host comprised four battles, or divisions, of cavalry. Led by Roger Bigod, Earl Marshal of England, and the earls of Lincoln and Hereford, the 18 bannerets (knights leading their own troops) and 430 knights and troopers of the vanguard were the first into the fray. Descending Redding Muir, they crossed the upper reaches of Westquarter Burn and headed directly north toward the Scottish line. Shortly after Bigod’s riders crossed Glen Burn, near its confluence with Westquarter Burn, their horses went slipping and sliding across the swampy valley floor, abruptly halting the advance. After some confusion, the re-formed van skirted the western edge of the bog. Continuing uphill, the English knights soon gained the flank of the Scottish right, where Wallace’s cavalry bided their time. Meanwhile, John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey and the loser at Stirling Bridge, led his battle of 15 bannerets and 410 knights and troopers in the wake of the van, wisely skirting the boggy loch to the enemy’s front before also gaining the Scottish right.

Next to ride out was the battle commanded by Bek, the warrior bishop, numbering two dozen bannerets and 400 knights and troopers. Having also witnessed the van’s discomfiture, his cavalry kept Westquarter Burn to their left and veered eastward around the bog. They had scarcely cleared the obstacle when many of Bek’s leading riders, rash and eager to come to grips with the enemy, spurred their mounts and left their countrymen behind. Rather than attack in piecemeal fashion, Bek ordered the others to await the arrival of Edward’s battle, the largest of the four with 43 bannerets and 850 knights and troopers, shielded by 100 mounted Gascon crossbowmen. Bek’s supremely arrogant deputy, Sir Ralph Bassett, the former English governor of Edinburgh Castle, had no intention of waiting for the king and rudely chided the bishop for his caution. Heedless of Bek’s attempts to restrain them, Bassett and the other glory-seeking knights continued uphill toward the dense masses of Scottish pikemen.

As Bek’s cavalry charged the waiting pikemen on the Scottish left, the ground trembling from the thundering hooves of more than 400 chargers, Bigod’s vanguard challenged the Scottish cavalry on the right. Though they matched the English horse in numbers, the inexperienced Scots were outmatched by Bigod’s heavily armored veteran knights and quickly driven from the field in an unseemly rout. Several contemporary narratives accused the high steward’s cavalry of withdrawing without striking a blow. But a handful of courageous knights did dismount and join the hollow schiltrons to fight afoot.

Having dispatched Wallace’s cavalry with alarming ease, Bigod’s van thundered into the schiltron on the enemy right while Bek’s riders attacked on the left. The tightly packed ranks of Scottish pikemen readily repulsed the ensuing armored onslaught, their bristling masses of iron-tipped 15-foot pikes presenting a seemingly impenetrable barrier. Unable to break through the dense walls of steel, both English cavalry forces fell back in good order, having suffered light losses in men and horses. Mustering another charge, they turned their attention to the vulnerable Scottish archers in the gaps between the static schiltrons. Guisborough described the resulting chaos as the overwhelmed archers fought desperately, clustered around the body of their leader, Sir John Stewart, “who fell by chance from his horse and was killed.” They stood no chance against the armored English riders and mounts. The few surviving Scottish bowmen sought refuge among the ranks of their fellow pikemen. Thus the immobile schiltrons were left isolated and alone, with no means to mitigate the seemingly impossible odds they faced.

Battlefield conditions had changed profoundly to the benefit of the English, and Edward had yet to commit any part of his massive infantry. Recalling his years fighting pikemen in northern Wales, Longshanks knew Wallace’s schiltrons were little more than sitting ducks. Throwing off any remaining caution, he brought his entire force to bear against the beleaguered Scots. After sending his regrouped and refreshed cavalry units against the enemy flanks, Edward advanced his 5,500 Welsh longbowmen and 400 Gascon crossbowmen into line opposite the Scottish front at extremely close range, about 100 yards. He then split his 7,000 spearmen, placing half on either side of the longbowmen. A fearsome sight, the English front numbered nearly 13,000 troops. Longshanks then ordered his missile troops to loose steady, sustained volleys of arrows, crossbow bolts and slingstones.

As they needed both hands to wield their long pikes, Wallace’s men were unable to bear shields in their defense. Most were clad in rough tunics of homespun cloth. Few had helmets or any form of armor to shield them from the unremitting torrent of murderous missiles that rained down on them. The Scots were particularly fearful of English longbow arrows, which were accurate to a range of 200 yards, generated enough force to pierce chain mail and plate armor, and could pin a knight to his horse. From astride their mounts at the center of the English line, Edward and Bek watched in satisfaction as their longbowmen, crossbowmen and slingers fired salvo after salvo into the Scottish ranks. The barrage soon began to tell on the exposed schiltrons. Gaps appeared in the Scottish line, enabling the English cavalry to break through and hack and slash the pikemen at close quarters.

Edward finally sent in his spearmen to fight hand to hand. According to the English scribes of the Lanercost Chronicle, the remaining Scots, though assailed from all sides, “stood their ground and fought manfully.” Inevitably, however, the four shattered schiltrons collapsed, and the survivors broke and ran, grimly pursued by Edward’s horsemen and Welsh spearmen, who killed with abandon. Urged by his lieutenants to flee, Wallace followed them north into Callendar Wood and escaped into the mountains, leaving behind at least 7,000 dead Scotsmen. Though the English lost just two knights, upward of 3,000 English foot soldiers lay dead on the field—a testament to the ferocity with which the Scots fought against insurmountable odds.

King Edward’s 1298 campaign involved considerable expense, and while it destroyed the power of Wallace, it yielded few other results and didn’t come close to ending the war. Stubbornly determined to force the Scots to acknowledge his lordship, Longshanks led a series of grueling campaigns from 1301 to 1304 that forced the submission of many leading nobles. By mid-1304 Scotland was firmly in his grasp. English troops garrisoned its castles, and order was restored. On having Wallace cruelly executed in 1305, Edward hoped he’d finally cowed the Scots into ceasing hostilities. That hope was shattered in March 1306 when Robert the Bruce, Earl of Carrick and 7th Earl of Annandale, claimed the throne of Scotland, thus resuming the First War of Scottish Independence.

“Edward’s military prowess was such that he might have secured a consensual union of the Celtic regions, had he not repressed them so brutally,” historian Simon Jenkins argues. “As it was, he found himself in the familiar trap of England’s medieval monarchs, encircled by resentful Celts and opportunist French.” Longshanks died of dysentery in 1307 while campaigning against Robert the Bruce, who after two more decades of bitter fighting finally secured Scottish independence.

John Walker is a California-based freelance writer and a Vietnam War veteran. For further reading he recommends Freedom’s Sword: Scotland’s Wars of Independence, by Peter Traquair; In the Footsteps of William Wallace, by Alan Young and Michael J. Stead; and Stirling Bridge and Falkirk, 1297–98, by Peter Armstrong.