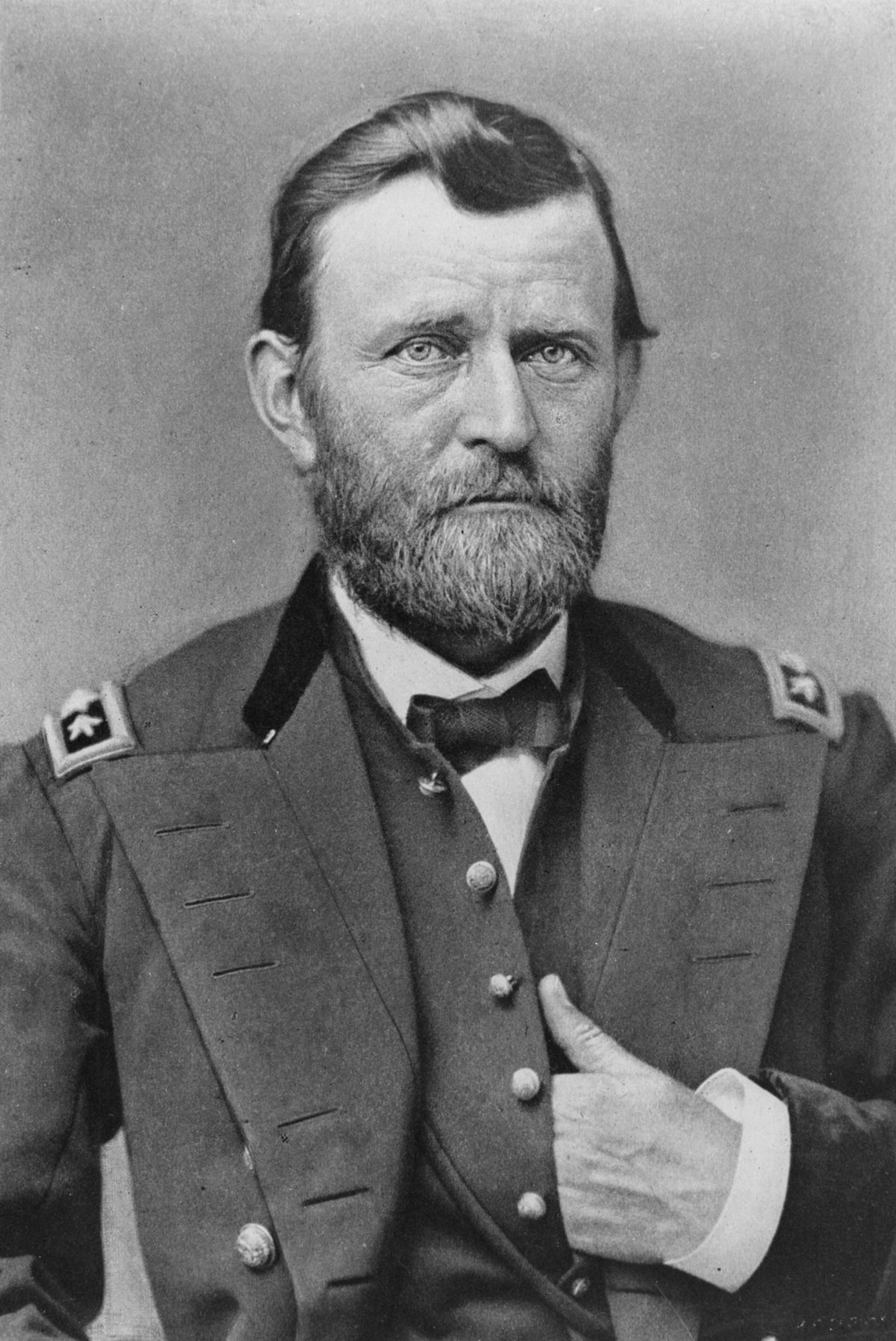

After Ulysses S. Grant won the Civil War, then served two terms as president of the United States, he didn’t know what to do with the rest of his life. So for 30 months he traveled around the world with his wife, Julia. They visited England, France, Germany, Italy, Greece, Russia, Egypt, India, Siam, China and Japan, among many other places. Grant was treated like visiting royalty, wined and dined at countless sumptuous banquets and forced to listen to endless speeches extolling his greatness. It was grueling, but Grant seemed to enjoy it, although he occasionally complained about the physical pain of shaking hands with hundreds of admirers, as well as the mental anguish of evenings at the opera.

Along the way, Grant met the Queen of England, the King of Siam, the Czar of Russia, the Prince of Wales, the Emperor of Japan and enough earls, lords, dukes, duchesses, viceroys, counts and viscounts to fill the Albert Hall. But perhaps his most interesting encounter came when he explained the meaning of the Civil War to Prince Otto von Bismarck, Minister President of the Kingdom of Prussia and “Iron Chancellor” of the German Empire.

They met in Berlin in June 1878, while Bismarck was presiding over the Congress of Berlin, one of those 19th-century gatherings where the rulers of Europe redrew the map of the continent to make it more to their liking. Grant did not attend the Congress; he was just passing through town. But when Bismarck learned of his presence, the chancellor sent a note to Grant’s hotel, inviting the general to visit him at the Radziwill Palace the next day at four o’clock.

Grant accepted. A few minutes before four, he walked out of his hotel, lit a cigar and sauntered down the street, through a park and up the palace steps, where he tossed away his half-smoked stogie, tipped his hat to the palace guards and prepared to knock on the door.

Astounding! Unprecedented! Where was his military escort? An honor guard to trumpet his arrival? Europeans were dumbstruck: An American president simply walked up to the door like a common peddler? Grant was about to knock when two liveried servants swung the door open and ushered him in.

Out bounded the chancellor. Bismarck, who never commanded troops on a battlefield, wore a general’s uniform; Grant, one of history’s greatest commanders, wore a business suit; Bismarck pumped Grant’s hand and welcomed him in fluent English.

Bismarck, 63, looked ancient, with a fleshy face, bushy white eyebrows and a droopy white moustache. Studying his visitor, he expressed surprise that Grant was so young. Grant replied that he was 56. “That shows the value of a military life,” said Bismarck, “for here you have the frame of a young man while I feel like an old one.”

Grant smiled and said he had reached an age when there was no higher compliment than to be called young.

After such pleasantries, Bismarck led Grant into his office, which overlooked a sunny park. The chancellor famous for uniting Germany was eager to talk to the general famous for reuniting the United States. But when Bismarck praised Grant for his military prowess, the general demurred. “The truth is, I am more of a farmer than a soldier,” he said. “I take little or no interest in military affairs. Although I entered the army 35 years ago and have been in two wars—in Mexico as a young lieutenant, and later—I never went into the army without regret and never retired without pleasure.”

Inadvertently, Bismarck had raised a question that Americans have debated, sometimes vociferously, for 150 years: Did the North fight the Civil War to preserve the Union or to destroy slavery?

“You are so happily placed in America that you need fear no wars,” said Bismarck, who ruled a country that bordered its rivals. “What always seemed so sad to me about your last great war was that you were fighting your own people. That is always so terrible in wars, so hard.”

“But it had to be done,” Grant replied.

“Yes,” said Bismarck. “You had to save the Union just as we had to save Germany.”

“Not only save the Union,” said Grant, “but destroy slavery.”

“I suppose, however, the Union was the real sentiment, the dominant sentiment,“ said Bismarck.

Inadvertently, Bismarck had raised a question that Americans have debated, sometimes vociferously, for 150 years: Did the North fight the Civil War to preserve the Union or to destroy slavery?

“As soon as slavery fired up the flag, it was felt—we all felt, even those who did not object to slaves— that slavery must be destroyed,” Grant explained. “We felt that it was a stain on the Union that men should be bought and sold like cattle.”

“I suppose if you had had a large army at the beginning of the war it would have ended in a much shorter time,” Bismarck said.

Recommended for you

“We might have had no war at all—but we cannot tell,” Grant replied. “Our war had many strange features. There were many things which seemed odd enough at the time, but which now seem Providential. If we had had a large regular army, as it was then constituted, it might have gone with the South. In fact, the Southern feeling in the army among high officers was so strong that when the war broke out, the army dissolved. We had no army—then we had to organize one. A great commander like Sherman or Sheridan even then might have organized an army and put down the rebellion in six months or a year, or, at the farthest, two years. But that would have saved slavery, perhaps, and slavery meant the germs of new rebellion. There had to be an end of slavery. Then we were fighting an enemy with whom we could not make a peace. We had to destroy him. No convention, no treaty, was possible—only destruction.”

“It was a long war, and great work well done,” said Bismarck, “and I suppose it means a long peace.”

“I believe so,” said Grant.

It was a remarkable conversation, wrote Grant’s biographer, William S. McFeely, a century later: “Grant was never more articulate about the war he had won.” The Union’s greatest general answered the oft-debated question of why the North fought, by saying—twice— that the cause of Union and abolition were inseparable, that the Union could not be preserved unless slavery were destroyed: “There had to be an end to slavery.” Grant apparently wished to communicate that message to a wider audience because he later repeated the conversation to reporter John Russell Young, who was chronicling the trip.

The general and the chancellor chatted a while longer, then Bismarck walked Grant to the door. Outside the palace, no carriage awaited, no honor guard, no color guard, no bodyguard. Ulysses S. Grant walked down the steps, fired up another cigar and strolled to his hotel.