Facts and summary information and article on Ulysses S. Grant, a union General during the American Civil War

Ulysses S. Grant Facts

Born

April 27, 1822. Point Pleasant, Ohio

Died

July 23, 1885. Wilton, New York

Initial Rank

Colonel, 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment

Highest Rank Achieved

Lieutenant General in command of all Union Armies

18th President of The United States

Battles Engaged

Battle of Fort Donelson

Battle of Shiloh

Siege of Vicksburg

Chattanooga Campaign

Overland Campaign

Siege of Petersburg

Appomattox Campaign

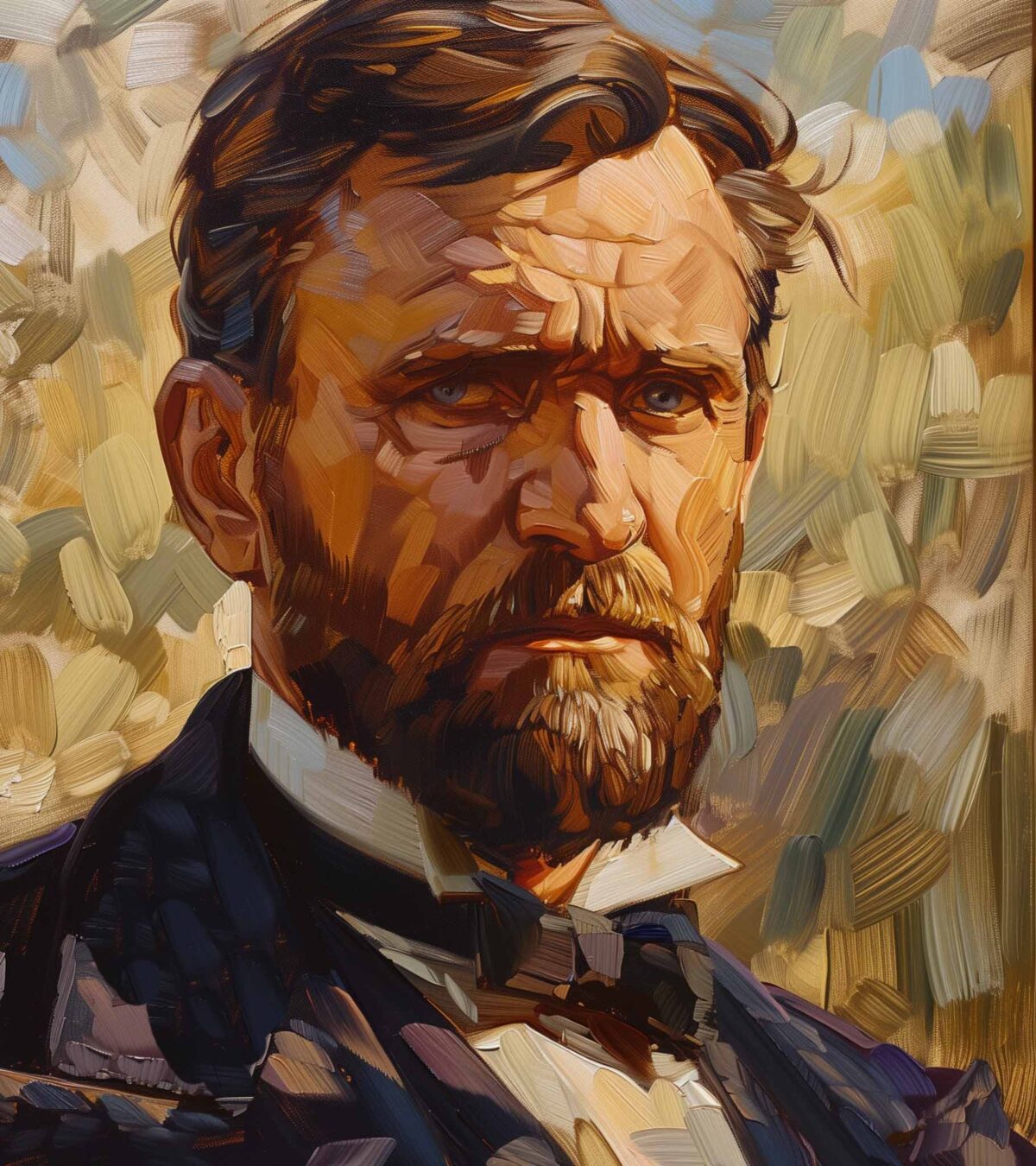

Ulysses S. Grant Pictures

Ulysses S. Grant pictures, images, and photographs

» See our Ulysses S. Grant Pictures.

Ulysses S. Grant Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about Ulysses S. Grant

» See all Ulysess S Grant Articles

Ulysses S. Grant summary: Ulysses S. Grant was born April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio, to a leather tanner named Jesse Grant and his wife Hannah Simpson Grant. His birth name was Hiram Ulysses Grant, but an error when he went to West Point changed it to Ulysses Simpson Grant. Simpson was his mother’s maiden name; she had used some of her connections to get him the West Point appointment. He allowed the error to stand and became U. S. Grant. To friends, he was known as “Sam.”

Grant at West Point Academy

Graduating 21st of 39 in the West Point Class of 1843, he served as a regimental quartermaster during the Mexican War, and developed a reputation for getting food and supplies over even the roughest terrain. A man of action, he would go to the front during battles, in disobedience of orders. At the battles of Molino del Rey and Chapultepec he was breveted for bravery and gallantry. Following the war, he was posted to the West Coast with the rank of captain, but resigned July 31, 1854, under suspicion of heavy drinking.

The question of the extent of Grant’s drinking, especially during the Civil War, is still debated today. He did partake of alcohol, but he suffered severe migraines and it is believed some bouts with these were reported as bouts of drunkenness. The boredom of frontier duty and longing for his beloved wife, Julia, likely did lead him to imbibe to excess. During the Civil War, his aide-de-camp, John A. Rollins, was a teetotaler who had seen his own father drink himself to death and the family into poverty. He informed Grant that the first time he saw his commander drunk would be the last day he would serve as his aide. Rollins was still with Grant at the end of the war. There were occasional stories of drunken binges, but none substantiated.

Grant had married Julia Dent, from St. Louis, on August 22, 1848. They were introduced by her cousin, an Army friend of Grant’s named James Longstreet. During the Civil War, Longstreet became a renowned general of the Confederacy as Grant’s star was rising in the Union Army. In 1880, Grant convinced President Rutherford B. Hays to name Longstreet ambassador to the Ottoman Empire.

After resigning from the army, Grant tried his hand unsuccessfully at several business ventures. In Missouri, he operated a farm, using one slave given to him by his slaveholding father-in-law. When the farm failed, Grant emancipated the man, William Jones, rather than selling him, even though Grant was in debt.

Ulysses S. Grant in the Civil War

When President Abraham Lincoln called for troops to put down the Southern rebellion, Grant, Julia and their children were living in a seven-room room in a well-to-do section of Galena, Illinois, and he was working as a clerk in the family’s leather goods store. Initially, he did not get a commission in the army, but with the help of Congressman Elihu B. Washburne, he was named colonel of the 21st Illinois Regiment, June 17, 1861. At the end of July, he was made a brigadier general of volunteers, to date from May 17.

Placed in command of a series of departments—one of which took him back to Missouri where he used his officer’s pay to settle with his old creditors—he first led troops in combat during the Civil War on November 7, 1861, at Belmont, Missouri. After initial successes, he was forced to withdraw his men when Confederate reinforcements arrived.

Grant at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson

In February 1862, he commanded the land forces in the Army-Navy operations in Tennessee that captured Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland, opening the door for the occupation of Nashville, the first Confederate state capital to fall under Union control. At Fort Donelson, his old friend, Confederate Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner, asked for surrender terms. Grant responded, “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender,” and he became known in the North as “Unconditional Surrender Grant”—a nickname inspired in part by his initials, U. S. His victory led to a promotion to major general.

An illustrator depicted him smoking a cigar at Fort Donelson—he actually was a pipe smoker at the time—and the published image resulted in admirers sending him cigars by the barrel. Perhaps not coincidentally, he would die of tongue cancer.

A Confederate sympathizer in a telegraph office intercepted and destroyed his messages to the War Department following the battle at Fort Donelson, and until the truth was discovered Grant was temporarily removed from command for failing to communicate with his superiors.

Grant At The Battle of Shiloh

On April 6, 1862, Grant’s Army of the Tennessee was surprised in its camps around Shiloh Church near Pittsburg Landing in southern Tennessee. Though pushed back a couple of miles, Grant held. Reinforced overnight by Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell with the Army of the Ohio, Grant and Buell defeated the Confederate army the next day, forcing it back to Corinth, Mississippi. Shiloh showed Lincoln that Grant was a general who fought hard, even under adverse circumstances. Over that spring and summer, Grant’s resolve with his Western army stood in stark contrast to the generals in the east: George B. McClellan had been driven back from the gates of Richmond during the Battle of the Seven Days; Nathaniel P. Banks was beaten at Cedar Mountain (Slaughter’s Mountain); and John Pope met defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Battle of Manassas). McClellan and Pope had retreated; in the West, Grant kept pushing south and west.

Grant turned his attention to Vicksburg, the Confederate “Gibraltar of the West” atop high, steep banks that gave it control of Mississippi River traffic. He was set back by a cavalry raid led by Confederate Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn that captured his supply base at Holly Springs while Grant was trying to invest Vicksburg from the rear. By December 1862, Grant had brought a sizable force down the Mississippi and began his campaign against Vicksburg in earnest.

Grant at Vicksburg

His first effort was a bloody repulse. He sent Major General William Tecumseh Sherman to take Chickasaw Bluffs north of the city, but the Confederates in their high, fortified position inflicted nearly 1,800 casualties. Over the coming months, Grant tried various operations on the rivers and bayous north of Vicksburg and digging a canal on the Louisiana side of the river.

As at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, he joined forces with the navy. On April 16, 1863, at Hard Times, Louisiana, south of Vicksburg, he and Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter carried out the largest American amphibious operation prior to World War II. Grant, perhaps drawing on his experiences as a quartermaster in the Mexican War, cut loose from his supply lines and let his men live off the land. They won fights at Raymond, Jackson, Champion’s Hill and Big Black River Bridge. By May 19, the first of his troops arrived northeast of Vicksburg. Again, he ordered Sherman to make an assault; again, Confederates in a strong system of defensive works repelled the Federals, inflicting about 1,000 casualties, in the first action of the Battle of Vicksburg.

Grant then settled into the siege of Vicksburg. For weeks, his men dug trench-works that snaked ever closer to the town. On June 25, they detonated barrels of black powder in a tunnel they had dug beneath the defenses, but were driven out by counterattacks. Finally, on July 3, the town’s Confederate commander, Lieutenant General John Pemberton, sent word he was ready to surrender his outnumbered garrison and the town in which the citizens had been reduced to eating dogs and cats—reportedly, even rats—because of the siege. The next day, July 4, Grant accepted Pemberton’s surrender. The siege of Vicksburg is still studied in war colleges around the world as a classic example of siege warfare. The Vicksburg Campaign was also an example of what made Grant an effective commander: he wouldn’t give up. If he tried one thing and it didn’t work, he would try others until he achieved his goal.

President Abraham Lincoln, when told that Grant was a “drunkard” and should be relieved of command, responded, “I can’t spare this man. He fights!”

Grant’s “Jewish Order,” Order No. 11

Lincoln did have to reprimand Grant, however, over an incident that occurred in December 1862. Grant’s father visited his headquarters, bringing with him several friends from Ohio, who turned out to be cotton speculators, men who would travel in the wake of the advancing Union armies, buy up cotton and sell it for a healthy profit to the cotton-starved factories of the North. Some of the men with his father were Jewish. Grant, angry over the cotton speculation that was causing corruption among the army’s officers, issued his infamous Order No. 11: “The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled from the department (i.e., Grant’s military district, the Department of the Tennessee) within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order.”

Congress went into an uproar, and in January, Lincoln told the War Department to rescind the order. It was an odd episode because Grant wasn’t known to be particularly anti-Semitic. He could display temper, however, in contrast to his usually quiet mien, and this was one of his outbursts. He later admitted to his wife that the criticism of his actions was well deserved. As president, he named several Jews to high positions and carried the Jewish vote in the 1868 election.

Following the success in conducting a siege at Vicksburg, he was called upon to break one at Chattanooga, Tennessee. In September 1863, the Union Army of the Cumberland and Army of the Ohio had been defeated in the Battle of Chickamauga in north Georgia. They had routed from the field and were now bottled up by General Braxton Bragg’s Confederates, who occupied the high ground around Chattanooga.

General Grant at the Battle of Chattanooga

On October 18, Grant was given command of all armies in the west. He went to personally take charge in Chattanooga though he was suffering the effects of a bad fall from his horse. From childhood, he had been known to have a special way with horses and was a superb rider, but this was the second time during the war he had been injured while riding. The first was prior to the Battle of Shiloh.

After a 60-mile trip overland, in which soldiers at times had to carry him when he was unable to walk those stretches, he arrived in Chattanooga soaked to the skin on the evening of October 23. He had already replaced the commander who had lost at Chickamauga, William S. Rosecrans, with the officer who had made a last-ditch stand that had saved the army, George Thomas. Grant approved a plan by Major General William “Baldy” Smith for breaking the siege to the southwest, and within five days a “cracker line” of supplies was opened.

Grant’s attacks against the Confederate right flank, beginning on November 23, were stymied. Lookout Mountain, the Rebels’ left, was captured in what became known as the “Battle Above the Clouds.” But it was an unplanned attack by Thomas’ troops in the center that swept the besiegers from Missionary Ridge and routed the Confederates. Seeing the Union soldiers climbing the ridge when they had only been expected to make a demonstration, Grant threatened whoever had ordered that attack up the slopes. No one had, as it turned out; the men just kept going, handing Grant a major victory.

That winter, Congress reinstated the rank of lieutenant general—a rank no field officer had held since George Washington—promoted Grant to it and put him in charge of all Union armies in March 1864. He had fought with, knew and trusted (to various degrees) the commanders in the Western Theater, where the story had been largely one Union victory after another. He entrusted command there to William T. Sherman, went east, and attached himself to the largest Union army, the Army of the Potomac, which had done little since its victory at Gettysburg the previous July. He left the victor of Gettysburg, Major General George Gordon Meade, in command of the army, but Grant traveled with it to keep his eye on things.

In the spring of 1864, he summarized his plans for the armies to President Lincoln. He intended to “employ all the force of all the armies continuously and concurrently, so that there should be no recuperation on the part of the rebels, no rest from attack.” He had grasped a truth that had eluded many other Union generals: even if the armies won no battles, they would win the war by continuing to advance, wearing down their outnumbered enemies. His object would not be to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, but to destroy the Rebel armies.

Farther south, his wife’s cousin James Longstreet was warning officers of the Army of Northern Virginia, “That man will fight us every day and every hour till the end of this war.” Longstreet would soon fall wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness.

Grant’s Overland Campaign

In May, the Army of the Potomac embarked on what is known as Grant’s Overland Campaign, a murderous slugfest of battles that took the federals from Northern Virginia to the gates of Richmond. The first clash came in the tangle of The Wilderness. After three days of intense fighting, May 5–7, with no gain in ground, Grant put the army in motion. He had lost over 17,000 men, and his soldiers wondered if this was yet another commander who spilled their blood, then retreated north when he failed to whip Confederate General Robert E. Lee. At a road junction, they realized Grant was leading them south, not north. Morale soared in the Army of the Potomac; the men began to sing.

Their commander was trying to maneuver past Lee’s right, get to Spotsylvania Courthouse and flank Lee out of his entrenchments in the Wilderness. Lee anticipated him, however, got there first and erected strong works. For two weeks, the armies battered each other in a series of fights along the front. On May 12, Grant’s men assaulted a semi-circular part of the defenses known as the “Muleshoe.” They broke through, capturing a division and nearly cutting Lee’s army in half, but the Confederates responded with a counterattack and the fighting raged for nearly 20 hours.

The next day, Grant again disengaged and tried to move past Lee’s right. Another 16,000 Federals would not fight again, but Lee had lost 12,000, in addition to 11,000 in the Wilderness. Grant’s meat-grinder was costly—Lincoln’s wife, Mary, called him a butcher—but it was achieving his goal. Lee’s army was being destroyed.

The man who had gotten Grant his first Civil War commission, Elihu Washburne, traveled with the army during the overland campaign, and as he prepared to return to Washington on May 11 he asked if Grant had any message for the president and the secretary of war. Grant said to tell them, “I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.”

Near Cold Harbor on June 3, Grant’s impatience led to a battle he later said he regretted badly. An uncoordinated series of attacks on Confederate works cost him 7,000 men—virtually all of whom died because the Union wounded lay between the lines for days while Grant engaged in a war of words with Lee, trying to avoid admitting a defeat. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles wrote in his diary the day before this battle, “Grant has no regard for human life.”

In reality, Grant did have regard for human life, but he used what he had—numerical superiority—to wear down his famous opponent. He continued moving around Lee’s right, crossed the James River, and got south of Richmond, where another Union force, the Army of the James under Major General Benjamin Butler was already operating. The two armies began a 10-month siege of the Confederate capital and the city of Petersburg, the main Confederate supply base for the region because of the railroads there. This denied Lee the mobility he needed for maneuver. The campaign became one of trench warfare presaging that of World War I, fought in a series of costly battles.

On April 2, 1865, Federal troops broke through the Confederate lines at Petersburg; by the evening of April 3, that city and Richmond were both in Union hands. Lee escaped with his badly diminished force, but at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, he met with Grant and surrendered his army. Grant, the “butcher” who had been unrelenting and uncompromising in pursuit of victory, extended very generous terms to the defeated Confederates.

On the night of April 14, when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theater, Grant and Julia might have been in the Presidential Box with the Lincolns. Newspapers that day said they would be present, but instead they left for New Jersey to visit their children.

Postwar, Grant, promoted to full general in 1866, oversaw the military aspects of Southern Reconstruction. He knew of Lincoln’s plans to “Let ’em up easy” and tried to follow that path until violent reprisals against the newly freed African Americans forced a crackdown.

President Ulysses S. Grant

In 1868, Grant won the presidency as the Republican candidate—both parties had courted him. His administration was scarred by scandal. Grant, a scrupulously honest man, was not personally involved and was reelected in 1872. During his second term, the nation entered one of its worse financial crises, the Panic of 1873, primarily because of over-speculation in railroads. A third attempt to make him the Republican presidential candidate in 1880 failed. Grant and Julia traveled extensively overseas and were feted by the crowned heads of Europe.

Their son Ulysses S. Grant, Jr. (“Buck”) borrowed $100,000 from his father to enter a partnership with Ferdinand Ward in the Marine National Bank and brokerage firm. Three years later, Ward asked for a loan of $150,000 for just 24 hours and Grant, unable to provide the money himself, borrowed it. Ward absconded with the money. Buck was left holding the bag; his parents sold their properties and traded their possessions to pay off the debt. Grant turned to writing articles for Century magazine about his Civil War experiences. He and author Mark Twain had become friends, and Twain arranged for a publishing company in which he was a partner to publish Grant’s memoirs.

Grant did not live to see them in print. In 1884, he was diagnosed with advanced cancer of the tongue. He spent the next year finishing the memoirs to provide income for his family when he was gone.

Ulysses S. Grant died July 23, 1885, shortly after turning in his manuscript. His memoirs sold very well, providing financial security for Julia and the children as the old general had hoped they would.

Featured Article

Ulysses S. Grant: The Myth of “Unconditional Surrender” Begins at Fort Donelson

In January 1943, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill met in secret near Casablanca, Morocco, for their second wartime summit meeting. At the final press conference on January 24, Roosevelt announced to the world that the Allies would not stop until they had the “unconditional surrender” of Germany, Italy and Japan. It was an impulsive statement by the American president, who later explained that the idea for it had “simply popped into my mind” while contemplating Ulysses S. Grant’s ultimatum to Confederates during the Civil War. At the time the pronouncement stirred a flurry of debate among British allies and his own generals, with the consensus of opinion being that it was a disastrous policy that would goad the Axis powers into a fight to the death. Who knew Grant’s shadow was so long?

Conventional wisdom has always pigeonholed Grant as a great military captain but a dreadful president. Both are true as far as they go, but there was another side to Grant that was just as important: He was a master of the art of surrender. As the byproduct of a string of battlefield victories, he forced the unconditional surrender of three enemy armies, something no other general officer in American history ever accomplished—not Dwight Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur, George Washington or Winfield Scott.

The learning curve for Grant began at the Battle of Belmont, Missouri, on November 7, 1861. The fight was little more than a raid, but it gave Brigadier General Grant his first experience with negotiating military terms. After that action he and several Confederate officers, including Benjamin Cheatham, met to settle a variety of issues, specifically prisoner exchange. The discussions were light and friendly, starting with reminiscences and other trifling matters such as horse-racing before proceeding on to serious matters.

But it was at Fort Donelson in Tennessee during his first negotiated surrender that Grant initially revealed the character traits and behavior patterns of the victorious captain. Operations against Donelson were part of an amphibious campaign launched in early 1862 to push the Confederates out of middle and western Tennessee, thereby opening a path into the Southern heartland. In cooperation with Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, Grant put together a joint task force of some 15,000 foot soldiers and seven gunboats to seize Forts Henry and Donelson, respectively guarding the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.

Foote won the first laurels by capturing Fort Henry while Grant’s forces were bogged down in the mud miles away. When the Confederate garrison commander, Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman, sent out a flag of truce asking the terms of surrender, Foote sent back a blunt reply, “No sir, your surrender will be unconditional!” In one sentence, Foote, the Navy man, had shattered all the old-fashioned and gentlemanly protocols of surrender.

When Grant and Foote turned their attention to Fort Donelson, they found an objective considerably more formidable than Fort Henry had been. Donelson sat on bluffs overlooking the Cumberland River, 12 miles east of Fort Henry. Fortunately for the Federals, the Confederates had made the fatal flaw of dividing their command among four mediocre leaders: Brigadier Generals John B. Floyd, Simon Bolivar Buckner, Gideon Pillow and Bushrod Johnson, with Floyd the senior officer and Buckner the only West Pointer. Although it did not seem significant at the time, Buckner had a history with Grant. The two of them had forged a very close friendship during their West Point years and also served together in Mexico.

Despite Confederate command problems, Donelson would be a tough nut for the Northerners to crack. Albert Sidney Johnston, the department commander, had proclaimed his determination to “fight for Nashville at Donelson, and [to use] the best part of my army to do it,” while a resolute Pillow announced that surrender was not in his vocabulary. The garrison that would have to back up those words was made up of 17,000-18,000 men strongly fortified behind earth-and-log bastions, supported by 17 heavy guns, situated on a high bluff that made them impervious to assault from the river side. The fort’s 2l¼2 miles of meandering landward defenses were its weak point, but even those were well sited.

The Confederates had their headquarters in Dover Tavern, in the village of Dover, while Grant set up his command post on the river steamer New Uncle Sam — oblivious to the irony. On February 15, he would place himself closer to the action by moving his headquarters to the log cabin of a Mrs. Crisp, some two miles behind Union lines. Foote’s flagship headquarters was the ironclad St. Louis.

Grant was still getting acquainted with his lieutenants, none of whom could rightly be mistaken for Napoleon Bonaparte’s field marshals. Two were politicians turned generals: John A. McClernand, a former Illinois congressman angling for Grant’s job, and Lew Wallace, an Indiana state senator, lawyer and part-time author before the war. The only professional soldier in the group was Brig. Gen. Charles F. Smith, who had come up through the old Regular Army and helped teach Grant the art of war when he was a cadet at West Point. Now the student was the commander and the teacher was the lieutenant. Grant’s immediate superior was Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, commanding the Department of the Missouri.

Grant opened the battle on February 13, hurling his newly bolstered force of 21,000 infantrymen against the Rebel earthworks in a series of uncoordinated attacks while the gunboats traded shots ineffectively with Confederate riverfront batteries. At the end of the day, neither the Federal army nor the navy had made much progress. A winter storm descended on the area that night, adding to everyone’s misery. The next day the infantry shivered in their siege lines while Foote, at Grant’s prodding, resumed his ineffective duel with Confederate batteries. After Foote was wounded and his boats were badly mauled, the navy withdrew, leaving it all up to Grant.

The second day’s fight encouraged the Confederates to go on the offensive on the third day to try to break out of their bottled-up position. When they struck early that morning, smashing into McClernand’s troops, Grant was off conferring with Foote onboard St. Louis. The situation quickly became critical. The Southern assault pierced the right of the Union line and threatened to collapse the center and left, held by Wallace and Smith respectively. Meanwhile both Union generals meekly awaited orders from a commanding general who was nowhere to be found. By noon, the Rebels had opened an escape route and Grant’s army was on the verge of crumbling when the day was saved by an inspired defensive stand from Wallace’s troops coupled with the timely arrival of Grant on the battlefield. Grant ordered an immediate counterattack and then went looking for his old mentor. He found the unflappable old gent sitting serenely under a tree whittling away while the battle raged nearby, but as soon as Grant ordered him to “Take Fort Donelson!” Smith leaped to his feet and quickly prepared an assault.

By the end of the 15th, the Confederates had lost heart and pulled back to their original lines, leaving Grant in tenuous control of the situation. That night at Dover Tavern, a gloomy Confederate council of war took up the question of capitulation. By consensus, they decided the situation was hopeless, with four of the general officers present (Floyd, Pillow, Johnson and Nathan Bedford Forrest) opting to escape the best way they could, leaving the disgraceful act of surrender to Buckner. Thus Buckner, mostly through no fault of his own, became the first general in gray to surrender an entire army. More important for this discussion, he became the first Confederate field commander who was forced to sue for peace terms.

Buckner gave his fellow generals a head start before beginning the painful process. He called for pen and paper to compose a message to his opposite number, though he was still not entirely clear on who that might be. Then he sent for a bugler and ordered him to sound the “parley” call, thereby alerting the Yankees that he wanted to talk. Finally, he sent a staff officer, Major Nathaniel Cheairs, through the lines under a white flag to deliver the message to the first general officer he met. This is the communiqué that Grant received sometime before daylight on February 16: “In consideration of all the circumstances governing the present situation of affairs at this station, I propose to the commanding Officer of the Federal forces the appointment of Commissioners to agree upon terms of capitulation of the forces and fort under my command, and in that view suggest an armistice until 12 o’clock today.”

Buckner’s parley note first came into the hands of Smith, who read it and snorted, “I’ll make no terms with rebels with arms in their hands—my terms are unconditional and immediate surrender!” Having expressed his opinion, Smith properly sent the courier and dispatch on to Grant, who decided to consult with Smith before composing an official response. The crusty old veteran told Grant the same thing he had said to Major Cheairs: “No terms to the damned Rebels!” This, in essence, formed the basis of Grant’s official response. Although Grant’s historic ultimatum of February 16 echoed the words already pronounced by Foote at Fort Henry and Smith to Major Cheairs, Grant would make no mention of being influenced by either Smith’s or Foote’s words in his memoirs, written many years later. One reason for the unusually blunt language was that Grant believed he was dealing with Pillow, for whom he had nothing but contempt, and that Buckner’s signature only meant he was the amanuensis for his commanding general. Grant sent a terse message back to Buckner: “Sir, Yours of this date proposing Armistice, and appointment of Commissioners, to settle terms of Capitulation is just received. No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.”

As a member of the brotherhood of Old Army officers and Grant’s personal friend, Buckner had every reason to expect a sympathetic reply from his counterpart. That was the way such things were supposed to work among gentlemen. Just 10 months earlier, after Fort Sumter surrendered, Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard had allowed Major Robert Anderson to march his troops out under arms while the victors formed ranks and delivered a salute.

But Grant was not Beauregard. Buckner was stunned by the tone of Grant’s reply and had to reread it several times. He had assumed that his forces would be allowed to go home with what West Point graduates had learned to call a parole d’honneur, although there was no formal protocol on such things between the North and South at this point in the war—and there would not be for another five months. What Buckner wanted was an extemporized agreement that would be strictly local and informal. Grant’s hard-nosed reply made him briefly consider taking back his offer to surrender, but he was in no position to be proud, with his men threatening to become unruly, his defenses breached and a parley already opened. For the rest of his life Buckner believed that if Grant had known who was in command at Donelson, then “the articles of surrender would have been different,” that is, more generous and chivalrous.

After weighing his options, Buckner decided that honor and protocol permitted no further resistance. He accepted Grant’s ultimatum, but sent back a reply that was more petulant than submissive: “The distribution of the forces under my command, incident to an unexpected change of commanders, and the overwhelming force under your command, compel me, notwithstanding the brilliant success of the Confederate arms yesterday, to accept the ungenerous and unchivalrous terms which you propose.”

The first high-level contact between the two armies involved Generals Wallace and Johnson, both of whom were freelancing. Accompanied by their aides, Union Lieutenant James R. Ross and Confederate Major W.E. Rogers, the generals met in front of Wallace’s lines, with Rogers given the unwelcome job of carrying the white flag. Following stiffly formal introductions, Wallace spoke first, asking whether the surrender was “perfected.” Johnson admitted that he did not know about the rest but his troops were already drawn up with their arms stacked and ready to be processed. Wallace ordered Ross to go with Rogers to carry the news to Grant’s headquarters, then he issued orders for his men to move forward and take possession of the Confederate lines. His orders included a strong prohibition against any taunting or cheering. Concluding their brief unauthorized parley, Johnson and Wallace rode into Dover. For the next several hours, Wallace continued to operate entirely on his own, ignoring the chain of command and acting as if Grant were a thousand miles away instead of only two.

Grant may not have had everything under control, but he was far from passive during this time. His first actions after receiving Buckner’s capitulation were sensible. He dictated orders repositioning his troops to receive the Confederate surrender. Then he ordered his quartermaster to assume control over all public property, and strictly forbade any pillaging in or around Dover. At that point, however, his natural impatience got the better of him. He simply could not stand the thought of being stuck at headquarters and out of the action. He could have let commissioners handle things—that was customary—and waited for Buckner to come to him in supplication, but he chose instead to go in person to Buckner’s headquarters to finalize the surrender. He was not concerned with following military protocol or showing who was in charge, and at this point he was still unaware that Wallace was trying to grab the glory. Grant simply wanted to settle matters face to face. As he would later tell Confederate General John C. Pemberton, “I do not favor the proposition of appointing commissioners to arrange the terms of capitulation because I have no terms other than [unconditional surrender].”

Grant’s approach to surrendering was the same as it was to fighting: pragmatic and unpretentious. He had no intention of holding a formal, parade-ground surrender ceremony, with the Confederate commander handing over his sword. Not only was Grant uncomfortable with such formality, but he had no desire to rub the Southerners’ noses in it; capitulation was humiliation enough. To finalize the surrender on this Sunday morning, Grant simply mounted up and rode through the lines into Dover, taking along minimal staff and no bodyguards. The fact that Confederate troops were “in a bad humor,” and therefore liable to take a bead on the first Union officer they saw, apparently did not enter his mind. He did not request a Confederate escort to ensure his safety, and there is no indication that he traveled under a white flag.

Up to this point, Grant had been upstaged by his subordinate officers, Wallace and Smith, who had interjected themselves into the process uninvited. Smith was subsequently consulted by Grant, but Wallace continued to act separate of the chain of command. On his own initiative he rode to Dover Tavern to see Buckner. Like Grant, Wallace had been friends with Buckner before the war, but that hardly justified his presence at Confederate headquarters without Grant’s authorization. And, according to Wallace’s account of the meeting, they did not confine their conversation to prewar reminiscences or simple pleasantries. Buckner nervously asked his friend, “What will Grant do with us?” Wallace, choosing his words carefully, replied that the Grant he knew would treat them as “prisoners of war,” whatever that implied.

Wallace was not the only officer on the Union side with his own agenda. Shortly after Wallace arrived at the tavern, another Union officer came through the door — Commander Benjamin M. Dove, who was on a mission to accept the surrender of the fort on behalf of the U.S. Navy. Dove would have claimed the honor of receiving Buckner’s sword too if Wallace had not gotten there first. The two Union officers had a brief discussion before Dove withdrew. Afterward the Navy suspended him for letting the Army claim all the credit.

Grant arrived at Dover Tavern an hour and a half after Wallace to find the two generals enjoying a traditional Southern breakfast of coffee and cornbread. Wallace offered no explanation for his presence at enemy headquarters, and such a breach of military etiquette startled even the phlegmatic Grant, causing him to later write in his memoirs, “I presume that, seeing white flags exposed in his front, he rode up to see what they meant and, not being fired upon or halted, he kept on until he found himself at the headquarters of General Buckner.” Wallace’s presence thoroughly annoyed Grant and began a rift between the two that never healed. Grant’s ire, however, did not extend to Buckner.

When Grant arrived he peremptorily took over possession of the tavern as his temporary headquarters. Then, with Wallace on hand as a witness, the formal surrender discussions commenced. Until this moment Grant had not realized whom he would be dealing with, expecting that it would be Pillow. Face-to-face with Buckner, he adjusted his thinking accordingly, and the subsequent mood of the discussion was one of unfailing politeness. Still, as Buckner recounted the event many years later to an English friend, neither commanding general seemed eager to get down to business. Instead they broke the ice by reminiscing about the old days together at West Point and in Mexico. They even managed a wry exchange about their present situation when Buckner observed somewhat defensively that if he had been in command of the fort from the beginning, Grant would not “have got up to Donelson as easily as [he] did.” Grant graciously conceded the point, adding that if Buckner had been in command, he (Grant) “should not have tried in the way he did.”

The light banter continued as Grant asked about the missing General Pillow. “Why didn’t he stay to surrender his command?” Grant inquired. “He thought you were too anxious to capture him personally,” replied Buckner, to which Grant quipped mischievously: “Why, if I had captured him I would have turned him loose. I would rather have him in command of you fellows than as a prisoner.” The banalities helped soothe Buckner’s ruffled feelings, allowing the discussion to proceed smoothly to more substantive matters. It was an approach that would serve Grant well in similar situations later.

Apart from Grant and Buckner taking each other’s measure, very little was settled at this first meeting. The two commanders agreed to cease all operations immediately, and Grant asked for details on the condition of Confederate forces. Buckner, more out of ignorance than deceit, was unable to provide much helpful information, but he agreed to do so as soon as possible. He asked permission to send out search parties between the lines to bury Confederate dead. Grant agreed and immediately issued the appropriate orders. This was an act of generosity that Grant later regretted, believing that large numbers of Rebels took advantage of the opportunity to melt away. Two years later, after the Battle of the Wilderness, Grant would not be so generous and trusting.

One of the first rules of negotiation is to try to reach agreement early on minor points, then build on that foundation in addressing more substantive matters. Even though he was untrained in the art of surrender, Grant did this instinctively at Dover Tavern. The first day’s session between the two men set the tone for hammering out the major issues the next day.

Buckner had more to worry about than the fate of his men. He was under indictment back home in Kentucky for accepting a brigadier general’s commission in the Confederate Army in September 1861. Now, having been captured in the act of bearing arms against his country, he faced the very real prospect of trial for desertion and treason. Grant could easily have placed him under arrest and held him for court-martial, which was what many Northerners advocated for former U.S. Army officers who had resigned their commissions. Yet he offered no judgments of Buckner’s choices and would not hold the sword of Damocles over his head. Instead, he treated the Confederate as the duly authorized representative of a legitimate government and kept focused on matters at hand. As he left Dover Tavern at the end of this first meeting, Grant made a magnanimous gesture completely outside the scope of traditional surrender protocols: He drew Buckner aside and offered him money out of his own pocket.

“Buckner,” he said, “you may be going among strangers, and I hope you will allow me to share my purse with you.” According to an observer who knew both men well, Buckner was grateful for the kindness but told Grant he had already made provisions “so that he would not require financial assistance.” Writing in his memoirs in 1884, Grant recalled it as a “friendly conversation,” an entirely different take than what Buckner described to an interviewer in 1904. Forty-two years after the fact, he recalled their conversation as a “rancorous exchange,” ending when he struck the purse out of Grant’s hand and stalked away. Either way, Grant’s offer was commendable.

It did not come out of the blue, however. Back in 1854, just after Grant had left the Army and was down and out in New York City, the two old friends had bumped into each other and Buckner had loaned the penniless ex-captain money to get home to Ohio. Now Grant had an opportunity to repay what was both a financial obligation and a debt of honor. Grant was not one to forget a kindness, no matter how much time had gone by, nor to let the business of war trump friendship. On the other hand, he would not let his personal sense of obligation interfere with his responsibilities as a U.S. Army officer. In the end, he delivered his old friend into captivity along with 50 other Confederate field officers, and Buckner would spend six months at Fort Warren, Massachusetts, until exchanged by formal cartel in August.

The final act in this little drama would come 24 hours later. In the meantime, Grant and Buckner busied themselves attending to the myriad details involved in giving and receiving the surrender of a large armed force. Lines had to be disentangled, the dead had to be buried, booty and prisoners had to be counted, transports had to be brought up to remove the POWs—and those were just the obvious things. Neither officer had any prior experience to fall back on, and the West Point curriculum did not include courses in how to surrender.

Grant made several errors of omission while feeling his way through his first surrender. For one thing, he should have appointed an experienced officer as provost marshal to handle the transfer of some 12,000 men. Instead things got so chaotic that Buckner complained to him on February 16, “There seems to be no concert of action between the different departments of your army in reference to these prisoners.” Still, Grant was more comfortable keeping a light hand on the reins.

Another consequence of his command style was that his senior officers, specifically Smith, felt free to hand out paroles to Rebel officers on their own initiative. Even Buckner got in on the act, insisting on issuing passes to his men that would be honored by Union sentries. Amiable as ever, Grant went along, seeing no harm in letting men move back and forth between the lines now that the fighting was over. This was another decision he came to regret. Finally, Grant was lax in regulating the behavior of his own men. In the first 24 hours of the truce, jubilant Union soldiers left their lines to parade through Confederate encampments with U.S. flags flying and bands playing. Only the intervention of Confederate officers prevented ugly confrontations with Rebel soldiers.

On February 17, in the salon of New Uncle Sam, the final terms were nailed down and the necessary documents signed. What would take no more than two hours to accomplish at Appomattox in 1865 took two days of dickering at Donelson before everything was settled.

It did not make Grant’s situation any easier that Buckner was a far tougher negotiator than Robert E. Lee, partly because Buckner was not shy about using his friendship with Grant to wring out every concession he could get, and partly because war-weariness had not set in and both sides still entertained hopes of ultimate victory. However, Grant was no gullible farm boy; his instincts were shrewd. For instance, he insisted on using his own headquarters on the second day instead of returning to Dover Tavern. He thereby forced his enemy to come to him, a valuable trump card in any peace negotiations.

When Buckner, accompanied by a pair of staff officers, came onboard New Uncle Sam, Grant was in conference with his senior officers. He got up immediately to receive the Confederates and make introductions all around. Then, since there were still substantive matters to be settled, they got down to business. Grant and Buckner took seats facing each other across a table in the center of the room while a recording secretary sat down at Grant’s elbow. Staff members arranged themselves behind their respective generals. As on the previous day, Grant was low-key, even affable, and steered the conversation away from politics and military affairs at the beginning. “Dignity and dispatch,” noted one observer, marked the day’s proceedings from beginning to end.

Neither brigadier general wore a dress uniform for the occasion, preferring to stay in campaign clothes—which were more suitable for a cold, wet February day. According to newspaper correspondent Charles C. Coffin, a witness to the affair, the short, round-shouldered, “rather scrubby looking” Union general, whose ill-fitting uniform emphasized his slight stoop, did not look the part of a victorious captain. But it did not matter, as Buckner hardly cut a dashing figure either, with his “meager whiskers” and mud-caked boots, casually attired in a “light-blue kersey overcoat and a checked neckcloth.” Their negotiations looked like the meeting of a couple of farmers across a pasture fence.

Besides their education and military background, Grant and Buckner shared a fondness for the occasional stogie. Both men lit up during the meeting, filling the small room with pungent smoke. Afterward the Northern newspapers picked up on this detail and recast it as a defining quirk of Grant. Those newspaper reports would result in thousands of admiring citizens sending him boxes of cigars, leading to a 20-cigar-a-day addiction—which eventually led to his death from cancer of the throat in 1885.

The first item on Grant’s agenda was getting detailed intelligence on the size and structure of the Confederate forces. According to Coffin, Buckner freely gave all the information Grant requested about Confederate fortifications, troop dispositions and the intentions of the high command. Grant was not indulging idle curiosity; the fact was, he did not have an intelligence operative on his staff to ferret out such information. As a result, he had only a fuzzy notion of what he had won.

For his part, Buckner was still trying to get all the wiggle room he could under the original “unconditional surrender” dictum. He asked for both military and humanitarian concessions, and as they talked, Grant began to realize just how many perfectly reasonable conditions could attend an unconditional surrender. Step by step, Grant backed off his original demand. Grant the relentless bulldog on the battlefield became Grant the compassionate conqueror at the peace table.

The suffering of Buckner’s cold and hungry men in particular touched the Union general’s heart. Grant had come to negotiate a surrender, not to feed the multitudes. Now he found himself in uncharted waters where no American commander had ever gone before. It was Buckner who broached the subject, explaining that his men had eaten almost nothing for two days, and now they were facing a delay of at least another two days before reaching their final destination. Could Grant see his way clear to provide food out of the ample Union stores?

This was Grant’s first notification of the chronically poor state of the Confederate commissary supply. It took him a few moments to digest this new information and respond appropriately. At first he demurred that he would like to help but his own commissary staff was not up to speed yet. Buckner did not give up so easily. “My staff is perfectly organized, and I place them at your disposal,” he said. Grant was a thoroughly practical man, and this was a practical albeit unorthodox solution. He accepted Buckner’s offer and issued the special orders for his commissary supply officers to deliver two days’ rations to the Confederates.

Buckner continued to lead the conversation, making additional requests, each of which received a fair hearing from Grant. For example, Grant “readily acceded to” Buckner’s request for “special treatment” for his wounded officers. It was not just their injuries that aroused his sympathy but the fact that these were brother officers, some of whom Grant knew well from West Point and service in the Old Army. That was the same reasoning behind his decision to allow commissioned officers to retain their side arms, although it meant that Rebel officers would be going into captivity carrying pistols and swords. Grant knew that an officer’s sword was more than just a weapon; it was the traditional symbol of his rank and authority. And many revolvers were family heirlooms that had great sentimental value. In the military world of rank and privilege, Grant was cognizant of both.

His generosity did not stop with opposing officers. Without Buckner even asking, Grant sent the sick and wounded of both sides off to Union hospitals in Paducah, Kentucky. “No distinction has been made between Federal and Confederate [casualties],” he notified his superiors. Grant agreed to let the rest of the Southerners, who were facing extended incarceration in prison camps, keep whatever clothing they possessed as well as blankets and “such private property as may be carried about the person.” By tradition, as Grant knew, POWs were relieved of everything but the clothes on their backs. Grant saw no need to impose unnecessary suffering.

In fact, Grant was proving so agreeable that it was beginning to seem as if there were no request he would refuse. If that was what Buckner thought, however, he had misjudged his opponent. Buckner asked that he be allowed to send a brief report to his department commander, Albert S. Johnston, explaining his actions. And he asked that his officers be allowed to send open letters to their families or friends back home to put their minds at rest.

Although the historical record is inconclusive on Grant’s response, there is no evidence that Johnston’s headquarters at Nashville received any communiqué from Buckner at the time. There is, however, good evidence that Grant allowed at least some correspondence of a personal nature to go out, in the form of a letter from Buckner to his wife Mary, which opens, “I am a prisoner of war.” It is dated February 18, 1862, and its contents suggest that Grant was not too concerned about military intelligence being leaked. In the letter, the general mingled professions of love with descriptions of final Confederate operations, the conduct of his two fellow commanders (Floyd and Pillow), Confederate losses and his destination as a POW.

As the discussions wound down, Grant continued to demonstrate exceeding generosity, charging Buckner to see to it that his troops laid down their arms and proceeded in an orderly fashion to the Dover landing, where they would board prison transports. Grant told Buckner to accomplish the objective however he deemed best, with the proviso that Confederate regimental and company grade officers should remain in command of their troops right up until the men boarded the transports. Even Buckner was struck by how trusting Grant was.

This was more than a matter of trust, however. Grant, it should be remembered, had no provost guard, no prisoner stockade and no experience handling large bodies of POWs. Simple necessity forced him to trust his enemies to be men of honor, and at least one of them did take advantage and escaped after surrender protocols were invoked. Johnson went over the hill on February 18, a prospect that Grant did not foresee when he telegraphed Henry Halleck two days earlier that he had both Johnson and Buckner in custody.

If he was less than rigorous about the details, it was because Grant did not consider himself a prison warden. He saw his job as winning battles and regarded the POW problem as a distasteful byproduct of victory on the battlefield. Concerning the thousands of prisoners captured at Donelson, he wrote his superiors that he would be “truly glad” to get rid of the lot of them. They were easier captured than taken care of, he groused, predicting they would “prove an elephant” for the government. His preferred solution would have been to parole all captured Confederates on the spot, but that decision was not his to make.

Grant was not so nonchalant about his own men being held by the enemy. During the first day’s fighting, Confederates had captured some 250 Yankees. While their river access was still open they had shipped these men to a point safely behind Confederate lines. Now Grant announced he would keep an equal number of Confederate prisoners behind until those men were returned. As for the rest, they would go to Cairo, Ill., to await further disposition. There is no evidence that Grant’s ploy was successful in prying Yankee POWs out of Confederate hands, but the fact that he made a good-faith effort is admirable.

After the last “i” was dotted and the last “t” crossed, Grant considered his work done. He wanted no stage-managed surrender ceremony that would demean the Southerners and force everybody to stand out in the cold, wet weather, and he certainly did not want Buckner’s sword. He felt so vehemently about it that when Dr. John H. Brinton, the army’s chief medical officer, asked when the official ceremony would be held where the Rebels marched by on parade, stacked their weapons and lowered their standard, Grant gave a waspish reply: “There will be nothing of the kind. The surrender is now a fact. We have the fort, the men, the guns. Why should we go through vain forms and mortify and injure the spirit of brave men, who, after all, are our own countrymen?”

Having won the victory, Grant did not waste time crowing about it either. He dashed off a perfunctory report to Halleck at St. Louis on the 16th, writing in the plural: “We have taken Fort Donelson….” The rest of the telegram was nothing more than an accounting of what was captured. He also sent off a brief handwritten dispatch to Brig. Gen. George W. Cullum, Halleck’s chief of staff at Cairo, commending his officers and troops for their performance. Unofficially, Grant was more exuberant in a letter to his wife Julia, calling Fort Donelson “the greatest victory of the season” and “the largest capture I believe ever made on the continent.”

The fruits of this victory were sweet indeed. The entire military situation in Tennessee and Kentucky now swung in favor of the North, setting the stage for the campaign that would ultimately wrest control of the Mississippi River from the Confederacy. The news reverberated as far away as London and Paris in short order. Halleck’s headquarters issued official commendations for both Grant and Foote, and Grant got a fast-track promotion to major general of volunteers. He became the man of the hour to a Northern public starved for victories early in the war. “Unconditional Surrender Grant” was largely a legend created by the Northern press, but it served him well. He never took credit for coining the phrase that first made him famous, and he remained the same man after Donelson as he had been before.