When the phone rang, novelist Nelson Algren was cooking dinner in his two-room, $10-a-month slum apartment in Chicago. He picked up the receiver and heard a woman speaking in a foreign accent.

“You have the wrong number,” he said and hung up.

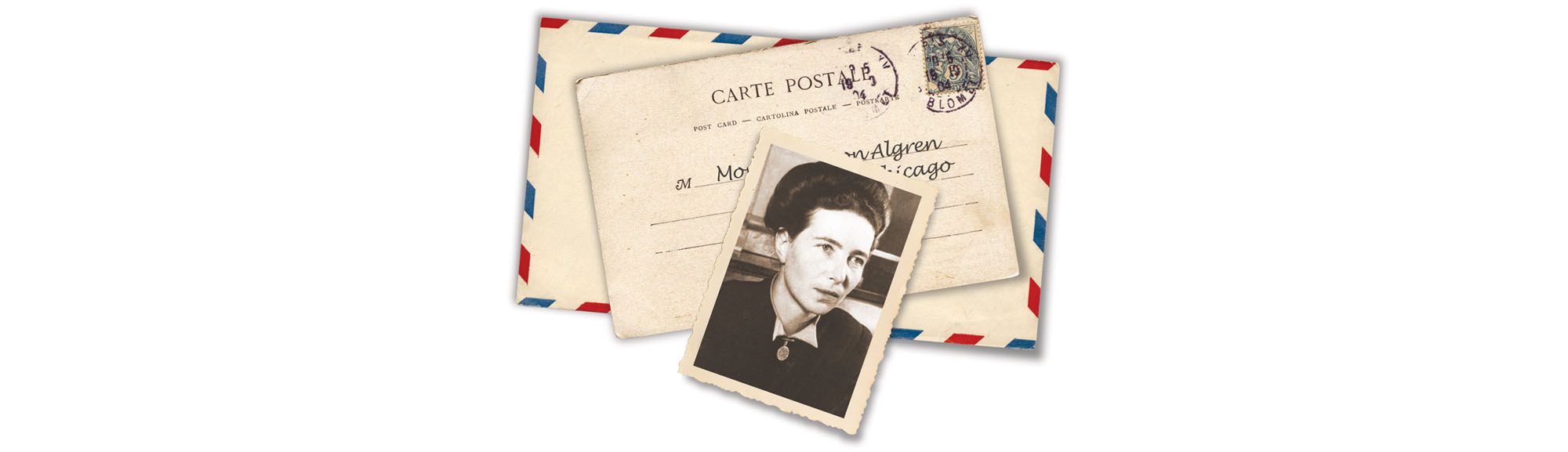

Simone de Beauvoir checked the number and redialed. Again the man answered and she tried to explain herself.

“Wrong number!” the man barked, then hung up.

What should I do? Beauvoir wondered.

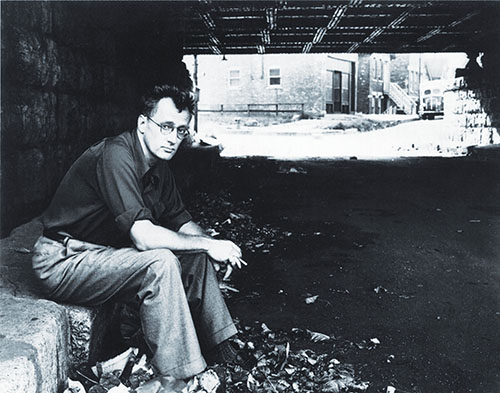

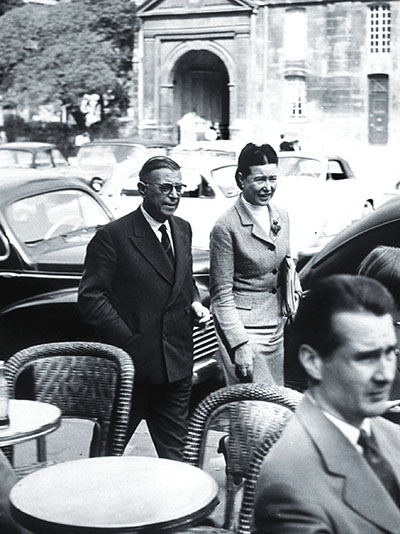

Back in France, she was a famous writer, author of three novels and essays that had helped define Existentialism, the school of philosophy that she and her lover, playwright Jean-Paul Sartre, had popularized. In Paris, their circle included the expatriate African-American writer Richard Wright, a pal of Algren’s who made his Chicago friend sound interesting to Beauvoir. Now, in February of 1947, Beauvoir was touring America for the first time, sightseeing and delivering lectures. In New York, a writer had given her Algren’s phone number. A Chicago factory worker’s son, Algren had spent the Depression hoboing around, selling goods door-to-door, pumping gas, and working as a carnival barker, until he stole a typewriter in Texas and landed in jail for four months. During the war, he’d fought in Europe. By 1947, he’d published two novels and dozens of short stories, most of them gritty, grim, funny tales of misfits, losers, and petty criminals.

Beauvoir wanted to meet Algren, and she didn’t know anybody else in Chicago. From her room at the Palmer House, she rang the hotel operator and asked her to dial Algren’s number.

“Please be patient and stay on the line,” the operator told Algren when he answered. He agreed and Beauvoir explained who she was and mentioned Richard Wright.

“Where are you?” Algren asked, his voice friendlier. “I’ll come down.”

They met in the Palmer House lobby and repaired to the bar. Algren, 37, was tall, thin, handsome, and witty. Beauvoir, 39, was petite, energetic, and curious, with eyes that were, Algren later wrote, “lit by a light-blue intelligence.” He bought her a drink, told her about his days fighting in France, and asked what she wanted to see. She deferred to him: Chicago was his town. He told her that he wrote about Chicago’s lowlife and offered to show her his world. She was game.

On West Madison Street, Chicago’s skid row, Algren led his guest into a seedy bar. The place was full of “bums, drunks, old ruined beauties,” Beauvoir wrote in her diary, and Algren seemed to know them all. A black jazz band started up. A sign read “Absolutely No Dancing,” but the barflies danced anyway. “A drunk asleep at a table wakes up and grabs the arm of a fat crone dressed in rags,” Beauvoir wrote in her diary. “They dance with a joyous abandon that verges on madness and ecstasy.”

Beauvoir watched, then turned to Algren. “It is beautiful,” she said. Algren found her comment very French. “With us, beautiful and ugly, grotesque and tragic, and also good and evil—each has its place,” he explained. “Americans don’t like to think that these extremes can mingle.” He did not add, though he could have, that those extremes frequently mingled in his writing, creating his unique mixture of tragedy and comedy.

“I’m going to show you something even better,” Algren said, escorting Beauvoir to a combination bar and flophouse. Drunks could buy a beer, then stagger upstairs to sleep in a big, empty room lined with mats. Algren introduced Beauvoir to Lorraine Kimion, who ran the place. “Everything I know about modern French literature is thanks to her,” he told Beauvoir. “She is very up-to-date.”

Beauvoir thought he was kidding.

“How is Malraux doing on his latest novel?” Kimion asked Beauvoir. “Is there a second volume? And Sartre? Has he finished Les Chemins de la Liberte? Is Existentialism still in vogue?”

A flophouse bartender who read Malraux and Sartre? “I’m stupefied,” Beauvoir wrote in her diary.

Late that night, Algren took Beauvoir to his apartment, and they made love. “I think he initially wanted to comfort me,” she later said, “but then it became passion.”

The next day, their exploration continued. “I showed her the electric chair, the psychiatric wards, neighborhood bars where I told her everybody sitting around was a sinister character,” Algren later recalled. “She looked around a while and then told me, ‘I think you are the only sinister thing around here.’ Then I took her to a midnight mission. I thought it was time to save her soul.”

The next day, Beauvoir resumed her journey, traveling to California, Nevada, Texas, and New Orleans. When she returned to New York, she invited Algren to join her. He did, moving into her room at the Brevoort Hotel in Greenwich Village. They went to a few literary parties but spent most of their time in bed. Before Beauvoir flew home, Algren slipped a ring on her finger. It wasn’t a wedding band, but she did write letters in which she addressed him as “my beloved husband.” And he wrote back: “I did not think I could ever miss anyone so badly.” The affair continued, on and off, for more than a decade. He visited her in Paris, she visited him in Chicago, and they traveled together in Mexico and North Africa.

In 1947, Beauvoir showed Algren an essay she’d written about women. He urged her to expand her thoughts into a book. She did, and The Second Sex became a feminist classic. In 1949, Algren published a novel about a Chicago junkie, The Man With the Golden Arm, which won the National Book Award. In 1955, Otto Preminger directed a movie version starring Frank Sinatra and Kim Novak.

Algren and Beauvoir exchanged torrid love letters but never lived together. Devoted to their work, they were not willing to move away from the cities that inspired their writing. In 1954, Beauvoir wrote an autobiographical novel, The Mandarins, featuring a moody American writer much like Algren. She dedicated the book to him, but he disliked the way she portrayed him, and mocked her in essays, asking: “Will she ever stop talking?”

It’s dangerous to fall in love with a novelist.

As the decades passed, Algren’s career faded while Beauvoir and Sartre, her companion and collaborator, evolved into literary celebrities. “She and Sartre became the Gracie Allen and George Burns of international left-wingism,” novelist Clancy Sigal joked in his review of a book of Beauvoir’s love letters to Algren.

Algren died in 1981, largely forgotten by American readers. Beauvoir died five years later, famous worldwide. She was buried next to Sartre in a Paris cemetery, wearing the ring that the interesting fellow in Chicago had given her 39 years earlier. ✯

This story was originally published in the November/December 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.