ONE WINTER 1894, a dozen prominent men, including two of SUNDAY in America’s greatest writers, William Dean Howells and Mark Twain, gathered at the Manhattan home of magazine editor Laurence Hutton, who had summoned them to meet an obscure 14-year-old girl from Tuscumbia, Ala. She was deaf and blind—the result of a mysterious disease contracted when she was 19 months old—but she had learned to speak, read and write in several languages. Her name was Helen Keller.

Escorted by her teacher, Anne Sullivan, Keller walked into Hutton’s library, where the other guests stood waiting. She must have smelled the leather-bound books that lined the room. “Without touching anything, and without seeing anything, obviously, and without hearing anything,” Twain recalled in his autobiography, “she seemed to quite well recognize the character of her surroundings. She said, ‘Oh, the books, the books, so many, many books. How lovely!’”

Keller was unable to hear conversations or to read lips, but she had learned to understand spoken words by holding her fingers up to the lips of the speaker and “feeling” the words. In Hutton’s library, as each guest shook her hand, she raised her fingers to Sullivan’s lips while her teacher spoke the guest’s name. After the introductions, Keller sat down to talk to Howells, the novelist known as “the Dean of American Letters.”

“Mr. Howells seated himself by Helen on the sofa, and she put her fingers against his lips and he told her a story of considerable length,” Twain wrote, “and you could see each detail of it pass into her mind and strike fire there and throw the flash of it into her face.”

When Howells finished, it was Twain’s turn to talk to Keller. His real name was Samuel Clemens, he explained, and his pen name was riverboat slang meaning a depth of two fathoms—12 feet.

She said the pen name made perfect sense because his writing was “deep.”

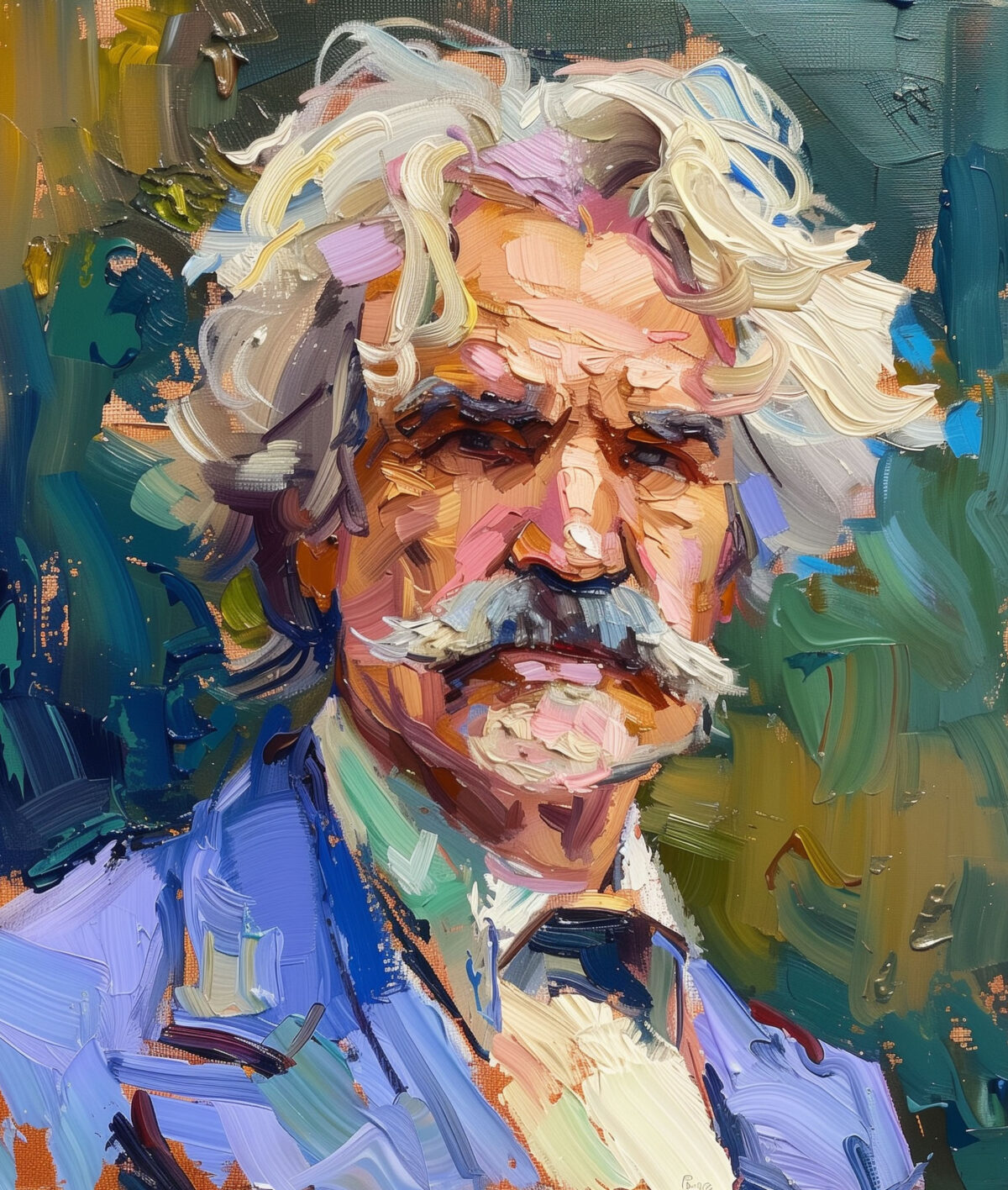

Flattered, Twain launched into a funny yarn, and she listened by holding her fingers to his lips as they moved beneath his bushy mustache.

“I told her a long story, which she interrupted all along and in the right places, with cackles, chuckles and care-free bursts of laughter,” he recalled. “Then Miss Sullivan put one of Helen’s hands against her lips and spoke against it the question, ‘What is Mr. Clemens distinguished for?’ Helen answered, in her crippled speech, ‘For his humor.’ I spoke up modestly and said, ‘And for his wisdom.’ Helen said the same words instantly—‘and for his wisdom.’ I suppose it was mental telegraphy for there was no way for her to know what I had said.”

With her fingers, Keller inspected Twain’s face, and his famous thatch of white hair. Then she took a flower from a bouquet she’d been given when she arrived and placed it in the buttonhole of his lapel. “The instant I clasped his hand in mine, I knew that he was my friend,” she later wrote. “I shall never forget how tender he was.”

“He was peculiarly lovely and tender with her—even for Mr. Clemens,” Hutton wrote, “and she kissed him when he said goodbye.”

A few years later, Clemens learned that lack of money might force Keller to end her education. He immediately wrote to the wife of his richest friend, Standard Oil executive Henry H. Rogers, suggesting that she convince her husband to help Keller: “It won’t do for America to allow this marvelous child to retire from her studies because of poverty.”

Rogers and other rich men agreed to pay for Keller’s education at Harvard’s sister college, Radcliffe, and in 1904, she became the first deaf and blind student to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree. Twain read some of her term papers and was impressed. “When she writes an essay on a Shakespearean character, her English is fine and strong, her grasp of the subject is the grasp of one who knows, and her page is electric with light.”

They kept in touch, exchanging letters and occasionally meeting. She loved to laugh at his stories and he loved to make her laugh. He was awed by her intellect and moved by her joyous optimism. She appreciated that he was never condescending and always took her opinions seriously. “He treated me like a competent human being,” she wrote. “That’s why I loved him.”

Their last meeting came in January 1909. Keller was 28 and, like Twain, a best-selling author. He was 73, rich and famous but depressed by the deaths of his wife and his daughter Susy. He railed against “the damned human race” but he never lost affection for Keller. When she sent him a copy of her latest book, The World I Live In, he wrote back, inviting her to visit, along with Anne Sullivan and Anne’s husband, John Macy.

They arrived at Stormfield, his huge country home in Redding, Conn., after a snowstorm that left the trees glistening with icicles. Twain wore his famous white suit and led them on a tour of the house, describing everything in vivid detail, while Sullivan wrote his words in shorthand on Helen’s palm.

“Try to picture, Helen, what we are seeing out these windows,” he said. “We are high up on a snow-covered hill. Beyond are dense spruce and firwoods, other snow-clad hills and stone walls intersecting the landscape everywhere. And over all, the white wizardry of winter.”

When they reached his billiard room, he told her that Rogers had given him the pool table. And he offered to teach her to play.

“Oh, Mr. Clemens,” she said, “it takes sight to play billiards.”

Not the way Rogers plays, he said. “The blind couldn’t play worse.”

At dinner Twain paced the dining room, telling stories. At bedtime, he escorted Keller to a guest room and showed her where she could find cigars and whiskey if she happened to wake in the middle of the night with a hankering for a smoke or a drink, as he frequently did.

The next day, Twain took Keller, Sullivan and Macy on a walk in the woods. “It was a joy being with him,” Keller remembered, “holding his hand as he pointed out each lovely spot and told some charming untruth about it.” On the way home, Twain got lost and it took him a while to find his house. “Every path leading out of this jungle dwindles into a squirrel track and runs up a tree,” he grumbled. “We have wandered into the chaos that existed before Jehovah divided the water from the land.”

“I never enjoyed a walk more,” she wrote.

She stayed for three days. On the last night, they all sat before a roaring fire and Twain read aloud his latest book, Eve’s Diary, while Keller listened with her fingers on his lips.

“His voice was truly wonderful,” she wrote 20 years later. “He spoke so deliberately that I could get almost every word with my fingers on his lips. Ah, how sweet and poignant the memory of his soft slow speech playing over my listening fingers. His words seemed to take strange lovely shapes in my hands.”

Originally published in the October 2012 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.