Noted gunfighter Ben Thompson and his younger brother Billy were among the Texans who had their hands full with the overzealous law enforcers in the Kansas community. By Richard H. Dillon

Newton, Wichita, Abilene and Dodge City were tough Kansas cow towns but none was tougher than Ellsworth, Abilene’s successor as America’s biggest stock shipping center. All these cattle communities had their share of notorious gunmen, but Ellsworth featured British-born Ben Thompson, who lawman Bat Masterson described as the most dangerous killer in the West.

Ellsworth was a violent place long before it was surveyed in 1867. It grew up around Fort Harker, where a ford on the military road from Fort Riley to Fort Zarah crossed the Smoky Hill River. Even before Fort Harker was erected in 1865, the area was teaming with bullwhackers, soldiers, Army scouts and buffalo hunters, not to mention Cheyennes and, sometimes, pro-slavery raiders. Probably the first local victim of Indians was Dutch Bill, scalped by Pawnees at absurdly named Pussy Cat Creek. At least once, the whole population fled to safer Salina. Real statistics are unavailable, but it is believed that Ellsworth had eight homicides in 1868, its first year as an incorporated village.

In 1872 Abilene told Texas cattlemen that they were no longer welcome, because of tick fever and the unruly conduct of Chisholm Trail cowboys. Agents like Abel “ Shanghai ” Pierce went down the trail to urge drovers to turn their herds toward Ellsworth, 60 mile southwest of Abilene. In 1871, while in competition with Abilene, Ellsworth had attracted between 28,000 and 30,000 cattle. The next year, 220,000 Texas Longhorns came up the Chisholm Trail to Ellsworth. Actually they traveled on a new route surveyed by a Kansas Pacific Railway Co. team headed by William M. Cox, general livestock agent for the railroad. This route, which saved about 35 miles, left the original trail in Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma ) halfway between the Salt Fork of the Arkansas River and Pond Creek and crossed the Arkansas River at Ellinwood, Kan. Sometimes called Cox’s Trail or the Ellsworth Trail, it is usually considered part (a middle branch) of the Chisholm Trail.

In 1867 a Kansas law had established a quarantine line, east of which no Texas steers were allowed. Ellsworth thought itself safe, but it was actually a few miles on the wrong side of the line. However, town promoters assured Texans that they would be exempt from the law. This proved to be the case, but mainly because the law was not enforced. Locals said that it was violated daily.

Boasting the biggest stockyards and six cattle chutes on a Kansas Pacific Railroad siding, Ellsworth attracted more than cattle and cowboys. It was a magnet, or a lodestar, for an army of ruffians. Foremost among them was Ben Thompson, who was born in Yorkshire in 1842 and migrated to the United States in 1851. He was 18 when he shot to death his first victim; he then killed another man in a New Orleans knife fight. While serving in the Confederate Army, he killed a fellow Confederate soldier. He was later jailed in Austin for killing his own brother-in-law, who had been abusing Ben’s sister. Before arriving in Ellsworth, Thompson and Phil Coe ran the Bull’s Head Saloon in Abilene, where, in 1871, Marshal Wild Bill Hickok shot Coe dead.

Wild Texas trail herders, reinforced by gamblers such as Thompson, locked horns with Kansas farmers as well as townsfolk. The grangers, or nesters (called sodbusters by the cowboys), hated Texans because their “Spanish” Longhorns carried a disease that killed domestic shorthorn cattle. Chisholm steers were immune, but off them dropped ticks that were the vectors of dreaded splenic (or splenetic) fever. Small wonder that Kansans called the tick fever “Spanish Fever” and “Texas Fever.”

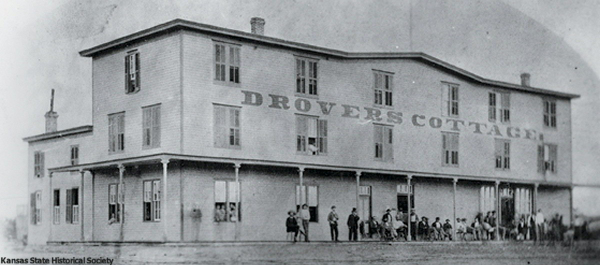

During its heyday, Ellsworth was proud of its two fine hotels—the Grover’s Cottage, hauled over from Abilene ; and the posh three-story Grand Central Hotel. The latter bragged of being on the only paved sidewalk in western Kansas. It was 12-feet wide, of fitted limestone slabs instead of the splintery planks of the usual boardwalks.

Most of the 16 saloons, like the gambling dens, stayed open till 3 a.m. The rest never bothered to close their swinging doors. Saloon keepers had to fork over from $100 to $500 a year for licenses. The many brothels, politely known as honky-tonks, were restricted to a red-light district, Nauchville, on the edge of town. Proper citizens tut-tutted its brazen, painted hussies but had no objections to the city receiving $300 a month from prostitution fines.

When an old-timer was asked it if was dangerous to go out at night in the 1870s, he hedged, “If persons kept sober and attended strictly to their business, it was not as dangerous as it appeared.” Still, Kansan newspapers carried phrases like “As we go to press, Hell is still in session in Ellsworth.” No doubt popular writers have exaggerated the violence in all cow towns. Ellsworth probably had as many as five homicides in one year only once, in 1873. Dodge only reached that number in 1878. Of course, stabbings and shootings, probably involving fatalities, usually went unrecorded in nasty Nauchville.

Ellsworth tried to be a peaceful place. After a cowboy seriously wounded a law officer in 1871, the village organized as a city of the third class. The first order of business for the mayor and City Council in 1872 was appointment of a city marshal. A second meeting passed law-enforcement ordinances. Signs reading “The Carrying of Firearms Is Strictly Prohibited” appeared on North and South Main Street, flanking the railroad tracks. Guns were checked at the marshal’s office or in the back rooms of saloons.

When Longhorns jammed the stockyards, the police force was fully staffed. The city marshal, who was also chief of police, earned $150 a month in season; only $100 in winter and spring. His so-called deputies, actually policemen, earning $75 monthly, were added in the summer and discharged in the fall. But the council paid lawmen $2.50 for every arrest made. This bonus, taken from the fines and court costs of law breakers, spread a welcome mat for police corruption.

There was only one serious shooting in 1872 and it was not fatal. A man named Jim Kennedy, sore at cattleman Print Olive over a card game, grabbed a pistol hidden behind the bar at the Billiard Saloon. Kennedy fired five times and three of the slugs hit Olive, but the cattleman recovered. Someone, unnamed, found another unchecked pistol and shot the fleeing Kennedy in the hip. Kennedy was jailed, not hospitalized, but his pals engineered his escape during the night.

A business slump in 1873 led to prolonged stays by Texas cowboys. The summer sun, glaring down at the few patches of 90-degree shade, set nerves on edge. When bored cowboys shot up the town for fun, an annoyed City Council strengthened the police with men who were handy with guns. To afford them, the city fathers passed an ordinance requiring gamblers to pay the same fines as prostitutes.

The story of Wyatt Earp involving himself in the major shooting incident of 1873 is pure poppycock, dreamed up by Earp for his gullible biographer Stuart Lake. Likewise the titillating tale of a dance hall girl, or harlot, Prairie Rose, winning a $50 bet with a cowboy by prancing down Main as naked as a jaybird except for a six-shooter in each hand is almost certainly a myth.

The climate of violence was, in large part, fostered by something akin to police brutality. In their zeal for law and order, councilmen appointed John (‘Brocky Jack”) Norton city marshal. Brocky Jack arrived from Abilene bearing a bad reputation. Also appointed were an ex-Toledo policeman, John (“Long Jack”) DeLong and quick-on the-trigger John (“High-Low Jack”) Branham. The worst of a bad lot was the ironically named John (‘Happy Jack”) Morco, a surly, abusive, foul-mouthed illiterate. Morco was on the run from a murder charge on the Pacific Coast, and he openly bragged of having killed a dozen men there. (His ex-wife set the record straight; he had killed four innocent men who had tried to stop him from beating her up—again.) Joining the Four Jacks, as the gamblers called the quartet, was Edward O. Hogue, who doubled as a deputy sheriff.

The Four Jacks and their “wild card,” Hogue, zealously arrested cowboys and gamblers. Hogue nabbed Ben Thompson’s younger brother, Billy, who had just arrived with a trail herd from Texas. The charges, not all trumped up in Billy’s case, since he was a boozer and a brawler, were as varied as a grocery list—carrying deadly weapons, disorderly conduct, drunkenness, disturbing the peace and unlawful assault on the “deputy marshal” (policeman Hogue). The lawman escorted the young Thompson to police court, where he pled guilty and paid a $25 fine, including court costs.

The surprising lack of protest from Ben Thompson, spokesman for the Texans and a known gunman, emboldened the Four Jacks, who accelerated their arrests-for-cash program. One of them shot an accused lawbreaker in the thigh when the man supposedly resisted arrest. Then, on June 30, 1873, Happy Jack rearrested Billy Thompson, who was charged with “feloniously” carrying a revolver; “unlawfully” disturbing the peace; and “unlawfully” assaulting Morco. One wonders who wrote up the charges, since the unlettered Happy Jack could scarcely scrawl his own name.

Five witnesses, including Ben Thompson’s friend Sheriff Chauncey B. (“Cap”) Whitney, came forward under subpoenas by the p rose cution. Judge Vincent B. Osborne again fined Billy $10 and court costs of $15. Billy once more pleaded guilty, paid the fine and was freed. And Happy Jack collected another “two-fifty.”

Ben Thompson had been extraordinarily patient up to that point, but he now had had a bellyful of the officers’ extortion. He bluntly told Whitney that the town would have to curb the corrupt police, if it really wanted law and order. But the county sheriff had no authority over city police, except Hogue, who wore two hats as policeman and deputy.

A new mayor, Jim Miller, backed the get-tough tactics with “transients”—cowboys and gamblers. Moderates on the council discharged Morco, but a citizen’s petition led to his reappointment. From July 24 to mid-August 1873, 27 arrests were made—three times the number for the same period in 1872. Judge Osborne passed judgment on more than 60 cases in ’73.

When the council cut loose another officer in August, it deferred to Brocky Jack and let go of DeLong, the least obnoxious of the “four of a kind.” Ellsworth’s Chronicle preached against overprovocative display of six-shooters by officers, but the editorial had no effect, particularly not on Morco, since he could not read a newspaper or anything else.

Finally, on Friday, August 15, 1873, all hell broke loose in Ellsworth. Thanks to loans from Texan gamblers Cad Pierce, Neil Cain, John Good and George Peshaur, Ben Thompson had set up a gambling den in Joe Brennan’s saloon. Several “serial” card games were going on, but poker players cashed in their chips that day and drifted over to a high-stakes monte game. Cain was dealing, and Pierce was getting. Ben Thompson was among the onlookers. His hard-swigging brother, Billy, was not kibitzing but was bellied up to the bar, as usual.

Cain balked at Pierce’s desire to play for even higher stakes and asked Ben to get somebody to take the over-bets. Ben asked a half-drunk gambler from Texas, John Sterling, to do the trick. Sterling had the reputation of being lucky. He agreed, promising to split his winnings with Ben, 50-50. Sterling won more than $1,000 but abruptly got up and left the saloon. Brennan asked Thompson if he was going to let a tinhorn gambler cheat him like that. Ben said he thought that Sterling would pay up; he would look him up in the afternoon.

Around mid-afternoon, Thompson found Sterling in Nick Lentz’s bar. With him was lawman Morco. When Ben asked for his share of the winnings, Sterling, angry as well as drunk—and flushed with Dutch courage by the presence of an armed Happy Jack—slapped him in the face. The insulted Thompson lunged at Sterling, but Morco held him off at pistol point. Thompson contented himself with telling Morco exactly what he thought of him and then suggesting he get “that God damned drunk out of the way.”

Morco and Sterling left, and Thompson went back to Brennan’s saloon. There, he and Pierce discussed the recent altercation. Morco and Sterling suddenly appeared at the saloon’s doorway and bellowed, “Get your guns, you damned Texas sons of bitches!” Morco had either one or two six-shooters (accounts differ), while Sterling was armed with a shotgun.

Unable to borrow a gun in Breenan’s saloon, Thompson ran around the back of the buildings to Jake News’ saloon, where he had parked his own guns. Thompson picked up his two Colts and a 16-shot Winchester rifle, then headed to the train tracks, where hopefully wild shots would not wound innocent people. Billy Thompson, carrying a handsome $150 breechloading, double-barreled English shotgun that Pierce had given to Ben, followed his older brother. Still sloshed from too much raw whiskey, Billy ran with both hammers cocked. When he stumbled, one barrel discharged, and buckshot dug into the plank boardwalk at the feet of cattlemen Seth Mabry and Eugene Millett.

Ben Thompson took the shotgun away from his younger brother. As he did so, he heard Mabry or Millett shout: “Look out, Ben! Those fellows are after you!” Ben handed the shotgun back to Billy and took up a position on the railroad tracks. He egged on his enemies by shouting: “All right, you Texas murdering sons of bitches, get your guns!

If you want a fight, here we are!” At that moment, Marshal Norton joined Morco and Sterling, but none of the trio was eager to meet an armed Ben Thompson.

Sheriff Cap Whitney arrived on the run. Norton told the sheriff that he was going to arrest the Thompson brothers. Whitney stopped him, warning: “They’ll shoot you, Jack. I’ll go. They won’t harm me. ” He was right. Both Ben and Billy held their fire as the sheriff approached. Whitney told Ben that the whole thing was a mistake, adding, “Let’s not have any trouble.”

Ben replied that he was not looking for trouble but that he would defend himself and his kid brother if Morco wanted a fight. But then Ben suggested that the sheriff have a drink with Billy and himself, so that things could cool down. The older Thompson said he would have Billy put away the shotgun. Then Fate (damn her!) intervened, to arrange a scenario that uncannily resembled the incident in Abilene when Hickok, after shooting Ben’s old saloon partner Coe, accidentally killed his own friend, private policeman Mike Williams.

As the Thompson brothers entered the saloon with Sheriff Whitney, Bill Langford, a Texas pal, yelled a warning, “Ben, here comes Morco!” Turning, Thompson saw pistol-packing Happy Jack running toward him. Ben jumped into the alley between Brennan’s and a general store. The sheriff called out to Morco: “Stop! What’s the meaning of this?”

Morco had second thoughts about charging his formidable foe. “What the hell are you doing?” he asked the sheriff as he dove for the saloon door. Ben snapped off a hurried shot with the Winchester, but the rifle ball missed Happy Jack and buried itself either in the door frame or an outside post that supported the second-floor veranda. In his classic book Triggernometry, historian Eugene Cunningham called it the poorest shot of Thompson’s career.

Now it was Billy’s turn to get into the action. Still unsteady with liquor, the younger Thompson rushed out and fired just as the sheriff turned to him and said: “Don’t shoot, Billy! It’s Whitney.” The sheriff was too late. Buckshot tore into one arm and shoulder and penetrated his chest, causing a lung to collapse. (Local doctors could do little for him; neither could the post surgeon from Fort Harker. Whitney would die from his wounds three days later.)

As Whitney staggered and fell, Ben shouted: “My God, Billy! Look what you’ve done. You’ve shot our best friend.” In the ensuring confusion, Ben went to his room in the Grand Central Hotel, where he stuffed his pockets with shells and traded his Winchester for a shotgun. Cradling it, he paraded back and forth on the hotel’s famed paved sidewalk, like an Army sentinel, holding the whole town in check until his brother could vamoose.

More gunplay seemed certain, but nobody dared take on Ben Thompson. Some of his Texas buddies soon “forted up” in the hotel to back him up. Pierce went to the livery stable to fetch Billy’s horse. Cain collected some money and pushed the wad of bills on Billy, saying: “Take this. We figure you’ll need it.”

Billy Thompson indeed lit out of town, remembering his brother’s advice, “For God’s sake, leave town, or you will be murdered in cold blood.” Ben who did not realize the extent of Whitney’s wounds, further advised his brother to lie low in a cow camp for a few days until things blew over. Billy, though. high-tailed it all the way to Texas —but only after a last intimate visit with his lady love in Nauchville. (Billy would not be arrested and extradited until 1877. At that time, he was found not guilty of murder, as the shooting was deemed an unfortunate accident. Critics claimed that the acquittal was the result of the jury being bought.)

Ben was in some legal trouble himself. He declined Ellsworth Mayor James Miller’s request to surrender his weapons. Miller then sent ex-policeman Ed Crawford to round up the police force. DeLong had been discharged, but Hogue was still active, along with Norton and Morco. The mayor then demanded that Marshal Norton arrest Thompson. When Norton demurred, Miller fired the entire police force. But Hogue was still a deputy sheriff and, surprisingly, he had enough nerve to face the older Thompson. Ben agreed to surrender if Hogue would disarm Morco and Sterling first. All parties agreed to the deal, and the crisis was over.

When Miller tried to make DeLong the city marshal in place of Norton, the City Council balked and substituted Hogue. There was no house cleaning of the police department, though. DeLong became an officer again, as did Crawford and even the hated Morco. Only Norton, arrested himself for being drunk and disorderly, and the nonentity High-Low Jack Branham were put out to pasture.

A cocky Morco appeared before Judge Osborne to file a charge of “felonious assault” against Thompson. Cattlemen Mabry and Millett posted bond for Ben, and he was released on bail. Once again Morco had second thoughts about the dangerous Texans. The lawman failed to appear in court, and charges against Thompson were dropped.

About this time, a vigilance committee began to issue (illegally) “white affidavits,” exile orders against the city’s undesirables. Ben Thompson, knowing that his name headed the list, did not wait for one. Anyway, a citizens’ group had voted for a resolution to ban gambling in Ellsworth. Thompson took off for greener pastures, advising pals Pierce and Cain to do likewise.

When Ben’s friends asked Hogue to question Morco as to whether warnings were out for them, the new marshal refused. Policeman Crawford then butted in, itching for a fight—against disarmed Texans. He shot Pierce in the side, then finished him off by beating him on the head with his six-shooter. Next day it was Cain’s turn. He was “treed” by Happy Jack. Morco was aiming his six-shooters at Neil when Hogue intervened. Hogue not only saved Cain’s life but also enabled him get a horse and gallop out of town.

Angry Texan transients then shot up the town and threatened to burn the damned place down to the prairie sod. When the press demanded action, the vigilantes began patrolling the streets at night to prevent arson. Other vigilantes ransacked the rooms of Texans, searching for a rumored cache of firearms. The governor, who posted a $500 reward for Billy Thompson, sent his attorney general to see if the local government needed the state’s armed help. The attorney general reported back that the problem was guns in the hands of overzealous police.

Texans wired Ben Thompson to come back to Ellsworth and lead them in their fight for justice. But someone from the railroad—the station agent or the telegrapher—leaked the telegram. Trains from the east were searched at Salina for several days. But Ben was long gone to St. Louis, on his way to New Orleans.

Only 12 days after the shooting of Sheriff Whitney, the City Council again fired the entire police force. A weak choice for city marshal, a local barkeep, was succeeded by a strict but fair officer, J.C. “Charlie” Brown. It was policeman Brown, not yet marshal, who finished off Morco. Happy Jack was flagrantly violating the law by wearing two guns in public, and not just any two guns—they were John Good’s stolen ivory-handled Colts. When Brown ordered him to give them up, Happy Jack drew one of the Colts, much too slowly as it turned out. Brown shot him in the heart and then, for good measure, put a bullet into his head.

Ed Crawford ignored warnings that Texans would kill him in revenge for his murder of Pierce. He was shot in the stomach and head in a brothel of his choice in Nauchville. There were suspects but no arrests. Ed Hogue wisely left town and survived until 1877, when he was killed in the Black Hills of Dakota Territory. As for Ellsworth itself, it had given way to Wichita as the main Kansas cattle town by 1875. Ellsworth was settling down to the quiet existence of a farming center.

Ellsworth’s onetime top gunman, Ben Thompson, went on to become city marshal of Austin, Texas. In July 1882, Thompson killed Jack Harris, the owner of a variety store, in San Antonio. Thompson was acquitted of murder the following January, but on March 11, 1884, Thompson was back in San Antonio, and he and his pal, John “King” Fisher, were shot down by several men, including Joe Forster, who had been Harris’ partner.

California historian and longtime librarian Richard H. Dillon has written scores of books and articles on California and Western history. Suggested for further reading: Why the West Was Wild: A Contemporary Look at the Antics of Some Highly Publicized Kansas Cowtown Personalities, by Nyle H. Miller and Joseph W. Snell; and the Complete and Authentic Life of Ben Thompson: Man With a Gun, by Floyd Benjamin Streeter.

.