Hawkins, Drake, and their fellow English privateers served their queen, repelled the Spanish and made their fortunes in the age of sail.

On March 24, 1603, in the darkest hours of a new morning, the “Virgin Queen” of England breathed her last. No family and few close friends remained for the deathwatch, but the ghosts must have gathered in gory numbers to claim their own. Men long drowned or wasted of bloody flux off some distant shore or smashed by cannon shot on a heaving deck—those wracked shades would have waited for the woman they had served in life. Elizabeth I’s loyal “Sea Dogs” would have waited for the words that would once again set them nipping at Spanish bootheels.

From her assumption of the crown in 1558 Elizabeth’s reign was marked by intrigue, violence, war and an amazing degree of royal poverty (comparative to fellow rulers, at least). Born into a Europe riven by religious schism, the opening of direct trade by sea with Asia, and the early exploration and exploitation of the New World, the last Tudor monarch sought to protect her 4 million or so citizens from threats both external (notably Catholic France, Portugal and Spain) and internal (a divided population subject to fleecing by a corrupt bureaucracy). Fortunately for her, England had harbors and mariners in plenty— poor men in the main, many mere fishermen, but hardened by constant toil and expert in the way of the sea. From these Elizabeth recruited, encouraged and frequently supported the best captains. To their enemies these leaders morphed into yammering, snapping, vicious curs no better than pirates and common thieves; but the Virgin Queen and her subjects knew them proudly as Elizabeth’s Sea Dogs, guardians of England’s shores.

Sir Francis Drake is the legendary figure among Elizabeth’s favored captains and needs few words about his life: bred to the sea, terror of the West Indies, scourge of the Iberian coast, defiler of South America’s Pacific coast and first Englishman to circumnavigate the world [see “Sir Francis Drake: Pirate to Admiral,” by Wade Dudley, June/July 2009].

But other Sea Dogs also made glorious (or infamous) names for themselves in that distant time. Martin Frobisher found “gold” for his queen while seeking a Northwest Passage to the riches of the Orient, commanded a squadron against the Spanish Armada and died of wounds sustained in honorable action. Thomas Cavendish emulated Drake’s circumnavigation and earned a knighthood for the wealth returned to Elizabeth’s coffers. Richard Grenville joined the half-brothers Humphrey Gilbert and Walter Raleigh in attempting to settle colonies in the New World before falling to a bloody deck, his Revenge surrounded by a Spanish squadron. Some of these great captains were born to wealth, some to poverty; many spent most of their lives afloat, while others came to the waves later in life; almost all were Protestant, and all were servants of a Protestant queen. They sought fame and fortune (and were not above stiffing customs officials to keep more of that fortune) while setting the stage for the rise of a British empire. It is with Drake’s second cousin Sir John Hawkins, a Sea Dog who changed the tactics of the Royal Navy as he plundered his way around the Atlantic, the story must begin.

Born into a wealthy maritime family of Plymouth in 1532 (his father had visited the shores of the New World around 1527 and was a confidant of Henry VIII), Hawkins seemed destined from birth for command. In his mid-20s, already an experienced captain, he leveraged the family name to convince several wealthy merchants to form a trade syndicate. With their support and three ships Hawkins sailed for Africa, where he seized several Portuguese vessels carrying local commodities and several hundred slaves—clear acts of piracy by modern standards, though less clear to his Protestant crews and benefactors in that time of religious militancy.

The expanded fleet made its way to the Spanish Caribbean, where Hawkins sought to sell his newly acquired slaves. Local governors, under an edict to trade only with documented merchants and fearing the reach of Spain’s King Philip II, resisted Hawkins, but individual planters desperate for laborers on Hispaniola soon purchased half of his human cargo. Authorities in Santo Domingo sent troops to disrupt the English activities. Spanish cavalry captured two sentries, then skirmished with Hawkins’ forces before beginning negotiations. Hawkins, by all accounts a charismatic man, bribed the Spanish officer with 100 slaves (the sick and infirm ones he was unable to sell) and the caravel that carried them. In return, the crown representative released his prisoners and provided Hawkins a license (illegally, but it carried the weight of local authority) to sell his remaining slaves. It was the stick and the carrot— violence and the promise of more violence tempered by a bribe —a technique pioneered by Hawkins that soon became an English norm in dealing with Spanish officials in the West Indies.

Hawkins completed his business within weeks. Between trade and plunder his efforts had been so successful that, after loading his three vessels to the bulkheads, Hawkins contracted two Spanish merchantmen to transport the excess cargo, mostly hides. Unfortunately, he dispatched the vessels to an English merchant in Seville to dispose of the goods. Needless to say, Spanish customs officers impounded both cargoes. Yet the loss of the hides was the smallest portion of the treasures garnered by the expedition. His ships, safely at anchor in Plymouth before summer’s end of 1563, held the jewels, coins and other treasures gathered by trade or plunder. While history does not record the exact amount recovered by those who invested in the syndicate, it does mention their eagerness to support further expeditions.

A second trading voyage (1564–65) brought 60 percent profit to Hawkins’ investors, including his queen. Elizabeth provided the 700-ton Jesus of Lubeck and, just as important, tacit approval of Hawkins’ “trading” (including the plundering of Portuguese and Spanish ships), despite diplomatic protests from Spanish ambassadors. Occasionally allying with French Huguenot corsairs busily raiding Catholic shipping off the Ivory Coast and in the Indies, Elizabeth’s newly favored captain used bribery, trickery, threats and lies to secure trade rights in Spanish ports, even fighting a mock battle with Spanish militia to “force” them to take his cargo of slaves. At sea, and away from prying eyes, outright piracy helped fill his holds with Spanish treasure. Success only whetted the appetite of his investors, especially the Virgin Queen.

For a third voyage (1566–67) a newly married Hawkins handed the leadership of the trading fleet to a friend and experienced captain, John Lovell. Using the same tactics pioneered by Hawkins, Lovell cut a bloody path along the African coast before sailing for the West Indies. Unfortunately, he lacked Hawkins’ skills and charisma. When such skills failed, he apparently turned to force on Hispaniola, his men running amok. Not only did Lovell fail to turn a large profit for the syndicate, he managed to instill a deeper fear of the English throughout the West Indies.

Hawkins sailed on the heels of Lovell’s return with the largest trading fleet to that date: six ships and 400 men. He commanded Jesus of Lubeck (Elizabeth also provided the 300- ton Minion and food and supplies). Hawkins’ cousin Drake commanded the 50-ton Judith—his first official command, though he had sailed as an underling with two (possibly all three) of the previous expeditions. In the usual way Hawkins plundered his way along the African coast, adding two captured Portuguese ships and two French vessels to his fleet while taking slaves afloat and ashore. It was not a happy voyage, as religious discontent (a few Catholics among the Protestant Englishmen) simmered among the crew of Jesus. Even Hawkins failed to control his anger: After exchanging cuts with gentleman-seaman Edward Dudley in a knife fight, he threatened to execute the man but pardoned him at the last moment.

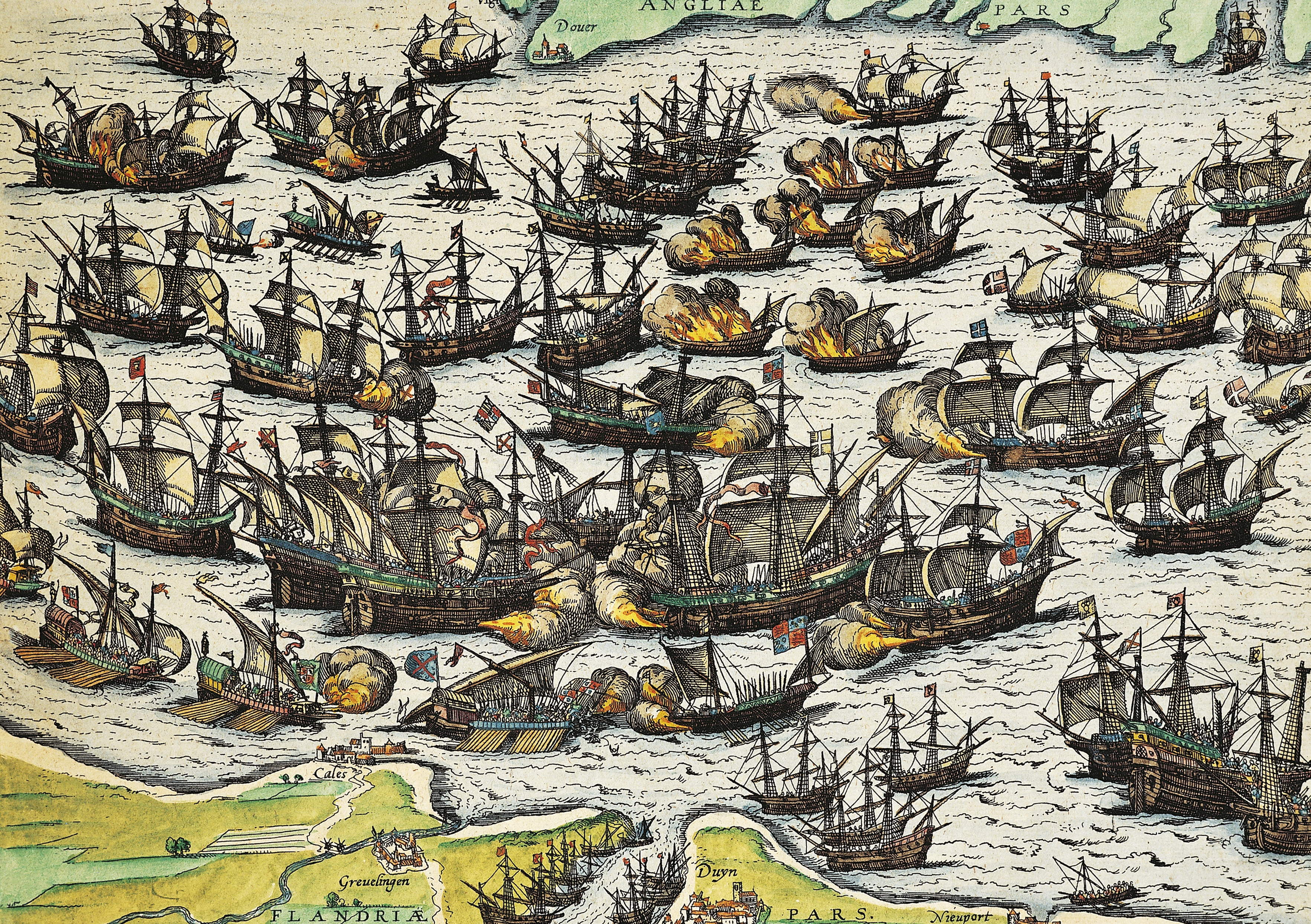

Things improved little in the West Indies. Though the isolated settlement at Dominica, already ravaged by French pirates, welcomed his fleet with open arms, Hawkins had to fight his way ashore at Borburata on the mainland. Afterward, the Spanish governor reported piracy, while Hawkins wrote of trade. After a repetition of violence at a second port, Hawkins received a license for local trade, parting with most of his cargo on favorable terms. Amid growing hostility, Hawkins decided to return to England. Unfortunately, the fringe of a hurricane caught his fleet at sea, damaging every vessel. Hawkins anchored in the Vera Cruz port of San Juan de Ulúa to effect repairs. There the annual Spanish treasure fleet trapped the Englishmen. Only two vessels, Minion, with Hawkins at the helm, and Drake’s little Judith managed to escape the vengeful Spaniards. Drake took aboard survivors from the overloaded Minion, and Judith sailed alone for England. Hawkins, short on food and water, put almost 100 volunteers ashore on the mainland of Mexico. These men found little mercy from the Spanish—only seven survived to see England again.

Hawkins watered his vessel somewhere in the Indies, then pointed his bow at England. Food shortages plagued his men, and when the weather turned cold, they began to die in great numbers. Reluctantly, Hawkins shifted his course to the northwest coast of Spain, where some personal friends resided. As he approached soundings, three Portuguese ships flung themselves at the battered Minion. The English Sea Dogs let them board; then, weak but still ferocious, they slashed their way to the decks of the enemy ships. Few Portuguese survived, and a vengeful Hawkins ordered those men tossed into the cold Atlantic—after an axman removed their legs. Stripping his prizes of food and useful materials, he ordered them scuttled.

After intimidating authorities at a small Spanish port into opening its markets to him, Hawkins’ crew feasted. Once again he tried to sail for Portsmouth, but another vicious storm drove Minion into the Spanish port of Vigo. There Hawkins found two English ships (dispatched by his father, William Hawkins) filled with the ropes, anchors and spars needed to refit Minion for its voyage home. Finally, in late January 1569, Minion and its pitifully few survivors returned to England. Of the 400 men that had accompanied Hawkins to the West Indies, only 50 or so ever saw home again. As to the plunder and trade goods once in the holds of his ships, Hawkins claimed that most of it had been lost to the Spanish. Perhaps—or maybe most of that loot made its way to family coffers.

Between plunder and profit Hawkins made a name for himself, beginning a career that saw his elevation to the highest ranks of Elizabeth’s advisers. Along the way he firmly established the triangular trade (England to Africa to the West Indies to England) forever tied to slavery in the Americas. He also managed to refocus the attention of Philip II on those English Sea Dogs and their heathen queen. As a courtier, Hawkins played key roles in espionage, served in Parliament and, in 1578, became treasurer of the Royal Navy.

In the latter role Hawkins championed the innovative “racebuilt” galleon, direct ancestor of the famed frigate of the 18th century. In crafting these vessels, shipwrights lowered the sterncastle and eliminated the bowcastle that defined earlier galleons, lengthened the keel and narrowed the beam of the ship, and reduced the armament (stressing quality and range over quantity of guns). These changes produced not only a faster warship, but also one that stressed long-range combat over the hack and slash of boarding actions that defined naval battle before the 17th century. Hawkins also pressed for multistage masts (allowing the lowering of the topmast in heavy weather and a corresponding improvement in stability) and flatter cut sails that made better use of the wind. By 1587 Elizabeth’s navy included 25 new or refurbished galleons and 18 smaller warships. They would be needed, as Philip, tiring of the English Sea Dogs nipping at his heels, prepared a great armada to send against England. In that year Hawkins resigned his post to take an active role in leading his warships against their enemy.

In 1588 Hawkins was third-in-command of the English fleet that met and defeated the Spanish Armada. The following year Hawkins sailed with the ill-fated Drake-Norris Expedition, hoping to destroy the surviving vessels of the Armada and intercept the annual treasure fleet. Poor planning—primarily by Drake—led to horrible failure. But the old hunting grounds of the West Indies still called Hawkins; in 1595 he joined Drake in a final expedition that twice failed to capture San Juan, Puerto Rico. Hawkins died at sea, a victim of disease, off that same island. Drake, beset by dysentery, followed him within weeks. Both bodies settled to the bottom of the waters that had once earned them fame and fortune.

Wh the West Indies, Sir Martin Frobisher earned his initial wealth capturing French vessels (Catholic ile Hawkins and Drake plagued the Spanish in or Huguenot—he did not discriminate). Born in the 1530s, Frobisher became intrigued with the idea of a Northwest Passage to open the riches of the East Indies to England while bypassing the southern routes dominated by Spain and Portugal. In 1576 Frobisher convinced the Muscovy Co. to support an expedition to the New World. Of the three ships under his command, only one reached the coast of Labrador, discovering the bay that still bears Frobisher’s name. As cold weather descended, a frustrated Frobisher returned to England. With him, he took a lump of black ore and the potential that Frobisher Bay could become an open route in warmer weather. When an assayer declared the ore as gold bearing (other assayers recognized it as iron pyrite—“fool’s gold”), Elizabeth took an immediate interest, providing a ship and money to charter two expeditions under the Co. of Cathay. Frobisher, elevated to commander of a fleet, claimed the inhospitable shores of Frobisher Bay for his queen, tried but failed to establish a colony, and could not find a passage to far Cathay (China), although he did return some 1,500 tons of ore to England. Sadly for Frobisher, it too was pyrite, and Elizabeth proved unappreciative.

Though fallen from his queen’s favor, Frobisher was needed to help thwart the growing Spanish menace. He eventually commanded a squadron against the Armada, earning a knighthood for his efforts. He then led a very successful raiding expedition along the Spanish coast for Sir Walter Raleigh. In 1594 he led a squadron to the relief of the French port of Brest, then under Spanish siege. A wounded Frobisher returned to Portsmouth but sailed alone to his ultimate reward a few days later.

While Hawkins, Drake and Frobisher served their queen for many years, Sir Thomas Cavendish burst across the waves like a falling star. Born to wealth in 1560, he lived in luxury. Inspired by Drake, the young man abandoned his parliamentary membership to sail with Sir Richard Grenville for Virginia in 1585. Upon his return to England, Cavendish received Elizabeth’s permission to operate against Spain. After building a 150-ton race-built galleon and purchasing two other vessels, Cavendish led his fleet from Plymouth in July 1586. At age 26 he planned to emulate Drake’s circumnavigation.

A little over six months later the small fleet exited the Strait of Magellan, raiding Spanish towns and capturing nine vessels as it sailed north. Questioning of prisoners led to the discovery that the Manila galleon, loaded with the wealth collected over the past year from Spain’s Asian trade, would arrive in the Gulf of California in October or November. Finding a quiet bay, Cavendish abandoned his prizes and his smallest vessel, refitted the two remaining ships and waited patiently. In early November the English spotted the 600-ton galleon Santa Ana. Throughout the day Cavendish’s ships pumped round shot and grape into the towering sides of the treasure ship, which had dumped its own cannon to haul more loot. Eventually, the crew of Santa Ana struck their colors as seawater began to rush through the vessel’s splintered hull. Loading his vessels with gold, silk, damask and spices, Cavendish fired the sinking hulk and put its crew ashore. Then his heavily laden warships sought the setting sun.

Cavendish’s aptly named Desire returned to Plymouth on Sept. 9, 1588. (His second ship had sailed into the Pacific darkness one evening and vanished.) Eventually, Desire wended its way up the Thames to London, where Elizabeth knighted her new favorite for his 26-month circumnavigation (and for the wealth he generously paid to her coffers). But fame and even greater wealth did not satisfy the young Sea Dog; by 1591 Cavendish had tired of English shores. In August he sailed to raid South American waters but suffered a severe defeat when attacking a Portuguese village in Brazil. Fully half of his crew fell to enemy fire, and shortly thereafter, at just 32, Cavendish followed them into oblivion—cause of death unknown.

Sir Richard Grenville, born to wealth and responsibility, epitomized the “hard man” of his time. Schooled in war while fighting as a volunteer for Hungary against Turkey in 1566 and putting down rebellions in Ireland, Grenville was a militant Protestant and had no problem creating martyrs—whether Muslim or Catholic. As a raider Grenville took several Spanish prizes but suffered much frustration while commanding the ships that delivered colonists to the coast of present-day North Carolina in 1585 and 1586, efforts that resulted in the “Lost Colony” once Elizabeth embargoed the fleet meant to resupply and reinforce the Roanoke colony in 1588. The vessels were needed against the Spanish Armada. Grenville missed the actual conflict against the Armada; he was busy sneaking two shiploads of supplies to the new colony. Unfortunately, French pirates took the vessels and stripped them of supplies before they could cross the Atlantic.

In 1591 Grenville commanded the race-built galleon Revenge and was vice admiral of the squadron observing the Azores when a fleet of 53 Spanish vessels loomed from the morning mists. Hugely outnumbered, Admiral Thomas Howard ordered his surprised squadron to withdraw at best speed. All ships did, except for Revenge. Grenville, with 100 of his men lying ill with fever belowdecks, refused to flee. Perhaps he sought to buy time for the squadron’s escape, perhaps the accumulated frustration and hatred had finally overcome his survival impulse, or perhaps it was simply a question of honor in the face of the despised Catholics. For 12 hours his vessel, completely surrounded, savaged the enemy. Pikes and swords ran with blood as ships ground together, only to drift apart. Shot tore men asunder, slashing rigging and smashing planks, turning decks into abattoirs. As Revenge’s magazine emptied of powder, and her crew slumped, dead and wounded, Grenville tumbled to the deck with mortal wounds. His surviving officers and crew surrendered, despite Grenville’s orders to destroy the ship rather than hand it to the Spaniards. Grenville died a few days later, still ranting at the cowardice of his men despite the 15 galleons they had crippled with their resistance. Revenge proved a bitter prize for the Spanish, destroyed by a hurricane within days of her captain’s death and escorted to the sea bottom by several of the galleons that had fought against her.

In later years Alfred Lord Tennyson immortalized the defiance of Grenville in “The Revenge: A Ballad of the Fleet.” He may well have spoken of all of Elizabeth’s Sea Dogs, of Hawkins and Drake and Frobisher and Cavendish and those not recorded by history or herein:

“I have fought for Queen and Faith like a valiant man and true;

I have only done my duty as a man is bound to do:

With a joyful spirit I Sir Richard Grenville die!”

And he fell upon their decks, and he died.

And they stared at the dead that had been so valiant and true,

And had holden the power and glory of Spain so cheap

That he dared her with one little ship and his English few;

Was he devil or man? He was devil for aught they knew,

But they sank his body with honour down into the deep.

Wade G. Dudley, a history professor at East Carolina University, is author of the award-winning Splintering the Wooden Wall: The British Blockade of the United States, 1812–1815 and Drake: For God, Queen and Plunder. For further reading he recommends The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain, 660–1649, by N.A.M. Rodger; Elizabethan Seamen, by R.R. Sellman; and Sir John Hawkins: Queen Elizabeth’s Slave Trader, by Harry Kelsey.