In 1780, with the American Revolution in full cry, one enslaved woman seized an opportunity to assert her freedom. Hearing the constitution of the new state of Massachusetts, which included the line “All men are born free and equal,” read aloud in the public square, she approached a neighbor for legal assistance. Mum Bett, as the plaintiff was known, filed a lawsuit to gain her freedom. For the first time in America, a suit challenged slavery’s constitutionality—and succeeded.

In recent years popular understanding of slavery in America has undergone a transformation, as historians have worked to portray in three dimensions enslaved individuals who were overwhelmingly illiterate and so unable to leave accounts of their own. The only glimpses of enslaved persons’ lives incorporated into the record were those that had been observed by White officials compiling census records, White slaveowners keeping ledgers, White newspaper editors setting the type of runaway notices, and White lawyers writing legal documents. In a limited but profound way, new and deeper scholarship has begun to rebalance that skew.

Most Americans think of slavery as a phenomenon that occurred in the southern states before the Civil War, typified by plantation settings populated by gangs of enslaved people oppressed by indolent slave owners. In fact, slavery was a going concern in all 13 American colonies. Massachusetts may be strongly associated with the abolitionist movement, but within ten years of Boston’s 1630 founding, that colonial and later state capital was a busy slaving port with people in bondage brought there to labor or be sold.

Slavery looked significantly different in New England. Historians distinguish between a “slave society”—a socioeconomic and legal system built upon slavery—and a “society with slaves,” a culture in which enslaved people were not the primary economic engine.

The New England colonies—Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island—became societies with slaves. By the beginning of America’s revolutionary era, New England was home to some 15,000 enslaved people. A third of those lived in the Massachusetts colony. These Black bondsmen and -women lived among few others of their kind: only 10 percent of the region’s colonists owned more than four slaves and 35 percent held just one. Women comprised 30 to 40 percent of the total New England enslaved population, typically sharing quarters with one or two other female slaves or even White indentured servants in a rural or urban household. That phrasing suggests an easier way of life compared with conditions down South, but slaves’ average life span—40 years—fell dramatically short of White colonists’ 70-year average.

The particular living conditions endured by enslaved persons in New England cut both ways. Any sense of Black community was scarce to nonexistent—but slaves had easier access to White conversation and discussion. The lively, often open-air, debates occurring after 1770 about liberty and equality found an eager audience among the enslaved. And as Enlightenment concepts took hold and cultural acceptance of slavery declined, owners around the region manumitted—freed—bondsmen and -women at an increased rate. In these tumultuous years, freedom swirled around the enslaved and looked like them, too.

The New England colonies were a unique environment for enslaved persons in other important ways. Reflecting as the region’s laws did a strong religious influence, New Englanders considered slaves not only property but persons. Some colonies also came to view only Africans as fit for slavery, even legislatively. Early in the colony’s history, natives captured in wars, considered too dangerous to remain in the colony, often were shipped to the West Indies to work as slaves on sugar plantations. An individual with an Indian or White parent was not considered Black and so could not be enslaved. Such colonial statutes offered legal paths to freedom. In the period before 1780 slaves in New England, 14 of them women, brought nearly 50 lawsuits. Women seeking legal redress faced even higher barriers than men. Authorities included enslaved women under the same law of coverture that applied to White women: wives were considered their husbands’ property and could not sue on their own behalf.

Historians have chronicled the stories of several enslaved female plaintiffs. In 1741, Elisha Webb was declared free by a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, court. Born in Virginia to a White woman and enslaved Black father, Webb became free at birth because of her mother’s race. However, Virginia typically indentured such children for 8 years when they reached puberty. Seven years in, Webb’s time was transferred to a Portsmouth sea captain who dared to sell her as “Elishea [sic] a negro.” Webb, who was literate, wrote to the Virginia judge who set up her indenture. By sending documentary evidence, she was able to prove her status as a free woman. In a similar 1767 case, Jenny Slew twice sued owner John Whipple, claiming Whipple had wrongfully enslaved her since her mother was White. On her second try, Slew won her suit in Salem, Massachusetts, and four pounds in compensation.

By 1774, when Juno Larcom brought a different suit in Salem, revolutionary rhetoric had worked its way into common parlance. The long-enslaved Larcom, a married woman, declared herself single in order to have standing to allege that she had been enslaved illegally, because her mother was an Indian.

Larcom’s impetus for bringing legal action was the sale of two of her children by an owner hard-pressed for cash. At trial, Larcom told the court, “Judge Ye Weather or noe I hadent ort to be set at Liberty.” The case was still underway when her owner died; afterward, Larcom boldly claimed her freedom. The owner’s widow gave up resistance and freed Larcom and her children, even giving the family a small residence on her property.

As significant as the Webb and Larcom cases were, only upon Mum Bett’s filing of her suit in 1780 does the language of equality appear in the legal record. Called Bet or Bett, she had been born around 1744; her precise birth date was not recorded. Her parents and their progeny belonged to Pieter Hogeboom, head of a wealthy Dutch family residing in Claverack, a town in New York near that colony’s eastern boundary with Massachusetts.

After daughter Hannah Hogeboom married John Ashley, seven-year-old Bett was sent 25 miles east to the Ashley home—now a historic site—in Sheffield, a town in Massachusetts colony. John Ashley was among the area’s largest slaveholders; Bett became one of five people he owned. Growing up in the Ashley home, she never learned to read; her story threads through historical records and White employers’ personal writings. At some point, she bore a daughter, called “Little Bett” or “Betsy.” Accounts differ regarding the father’s identity and whereabouts and the couple’s marital status.

John Ashley’s home in Sheffield was a center of pre-Revolutionary ferment. Ashley, a highly influential lawyer and local judge, had commanded a local militia during the French and Indian War. In 1773, he hosted a group of insurgents who wrote an early petition to the British crown. The Sheffield Resolves, as that manifesto became known, stated, “Mankind in a state of nature are equal, free, and independent of each other, and have a right to the undisturbed enjoyment of their lives, their liberty and property.” Though illiterate, Bett could not have helped but hear the words “equal,” “free,” “independent,” and “liberty” with a thrill.

A later sympathetic account describes Bett enduring repeated abuse from Hannah Ashley yet sustaining herself with a strong will. At one point, Bett incurred a bone-deep wound in one arm because she stepped in to prevent her mistress from striking Bett’s daughter with a hot shovel. “I had a bad arm all winter, but Madam had the worst of it,” the account quotes Bett as saying. “I never covered the wound, and when people said to me, before Madam, ‘Betty, what ails your arm?’ I only answered—‘ask missis!’”

Mum Bett’s opportunity to claim a free life came in the midst of the Revolution. In 1780, she was in her late thirties. With illiteracy widespread across the colonies, the authorities commonly read aloud important documents for all to hear. That was the case with Bett and the new Massachusetts state constitution. “All men are born free and equal and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights;” she heard, “among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.” This document, which chiefly was authored by John Adams and which was influenced by the Declaration of Independence, was approved by Massachusetts voters in June 1780. It is unclear whether Bett heard a reading before or after voter approval.

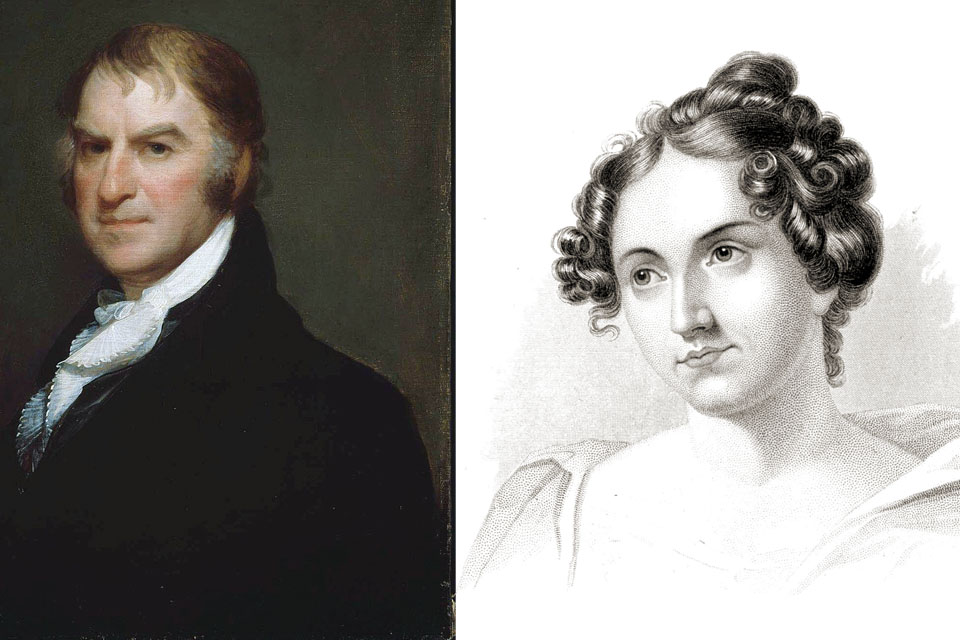

Shortly thereafter, Bett approached a neighbor, Theodore Sedgwick. A young lawyer, an early abolitionist, and a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Sedgwick had been among the drafters of the Sheffield Resolves. His daughter, Catherine, later sketched the scene between her father and Mum Bett. “’Sir,’ said [Bett], ‘I heard that paper read yesterday, that says, all men are born equal, and that every man has a right to freedom. I am not a dumb critter; won’t the law give me my freedom?’”

Sedgwick agreed to take Bett’s case. Soon, her litigation was combined with a freedom suit brought by another enslaved person owned by Ashley, a man named Brom. Sedgwick realized that Bett’s suit could serve as a means of determining whether slavery was legal under the new state constitution. Tapping Reeve of Litchfield, Connecticut, another patriot and renowned legal educator, joined the case. Some sources suggest that Sedgwick and Reeve were looking for a test case and chose the two defendants, though it’s not clear why only two or these two particular people would be the plaintiffs.

Sedgwick and Reeve began by filing a writ of replevin, a legal action that seeks the return of property illegitimately held. Ashley responded that both Bett and Brom were his rightful property for life. After Ashley refused to comply with two further writs, the court ordered a trial.

In August 1781, at Great Barrington, Massachusetts, the Berkshire County Court of Common Pleas heard the case of Brom and Bett v. Ashley. Addressing a jury of free White men, Sedgwick and Reeve argued that the language of the new state constitution effectively outlawed slavery. Though in 1781 these veniremen were hardly a jury of the plaintiffs’ peers, few jurors hearing the case were likely to own slaves. By the next day, the jury had found for Bett and Brom: the two were free people. Bett and Brom were awarded 30 shillings in damages. Ashley was ordered to pay six pounds in court costs. Ashley appealed but within months, after a similar suit was also decided in favor of the enslaved, dropped his appeal.

Another such case brought about the legal end of slavery in Massachusetts when on July 8, 1783, the state supreme court ruled in Commonwealth v. Jennison. In that finding the judge referenced the new state constitution’s declaration that “all men are born free and equal” in stating that “slavery is in my judgment as effectively abolished as it can be. . . .”

Mum Bett took the name Elizabeth Freeman and began to fashion a free life. John Ashley offered her a paid position, but she went to work for Theodore Sedgwick. Freeman acquired a reputation as a midwife and nurse. Sedgwick’s daughter Catherine, who disliked her stepmother, came to call Elizabeth “mother.”

Catherine Sedgwick’s sentimental 1853 reminiscence first revealed the story of Mum Bett. Catherine wrote that Elizabeth liked to recall her struggle for freedom. “I would have been willing if I could have had one minute of freedom just to say, ‘I am free,’” she remembered Elizabeth declaring. “I would have been willing to die at the end of that minute.”

The Sedgwick family employed Elizabeth Freeman until 1808, when she purchased and moved into a house of her own on nearby Cherry Hill Road. She continued to practice midwifery. In 1811 Catherine Sedgwick’s daughter Susan painted a miniature of Freeman, the only known likeness of her. The portrait presents a paragon of respectability wearing the white cap typical of women of that era, a blue dress, and a white neckcloth in the fashion of the day. Mum Bett wears a gold necklace given her by Catherine.

Elizabeth Freeman was about 85 when she died on December 28, 1829. She left a detailed will distributing her assets among her daughter, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. These included five gowns, including one in black silk; “a large home made birds eye petticoat” and a black velvet hat; pieces of furniture; three “green edged pie plates;” and her gold necklace and earrings. She is buried at Stockbridge Cemetery in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Catherine Sedgwick wrote on Mum Bett’s headstone, in part, “She could neither read nor write yet in her own sphere she had no superior nor equal.”

This story was originally published in the August 2021 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.